Could Spray-On Solar Change the Game?

We’ve heard a lot about falling solar prices. Some of that is due to dumping of low-cost panels from China. But there is also a great deal of research being done here in the U.S. and elsewhere that is attacking the problem from many different directions. This is helping to not only reduce cost but to increase efficiency as well.

One area that has shown promise is that of colloidal quantum dots (CQD). These tiny nanotech wonders have a theoretical efficiency of 45 percent, surpassing that of silicon, though no one has come close to achieving that yet. What has been done, however, by researchers at MIT, is the development of production techniques that allows quantum dots to be produced without elevated temperatures or vacuum conditions. That means low cost, with a present conversion efficiency of 9 percent.

One thing to keep in mind with solar is that, given the fact that sunlight is free, the efficiency by which it can be converted into electricity is less important than it is with other sources that require you to pay for the energy. Where it does matter is in two areas: the system cost and the amount of area required.

So if the system cost is low -- allowing you to cover your entire roof at a reasonable price -- which provides enough power even at low efficiency, then who cares? Still, you have all that mounting hardware and labor to install it, right?

The cool thing about quantum dots is that these solar cells can theoretically be sprayed on, eliminating all that mounting hardware and labor and also permitting the cells to conform to irregular and uneven surfaces. Another good thing about quantum dots is their ability to soak up a wider portion of the solar spectrum. One problem with them has been that they lose their effectiveness when they come into contact with oxygen.

Researchers at the University of Toronto, who have been testing out the possibility of spray-on cells, have found a way around the oxygen problem using different materials. “The field of colloidal quantum dot photovoltaics requires continued improvement in absolute performance, or power conversion efficiency," Professor Ted Sargent said back in June. "The field has moved fast, and keeps moving fast, but we need to work toward bringing performance to commercially compelling levels."

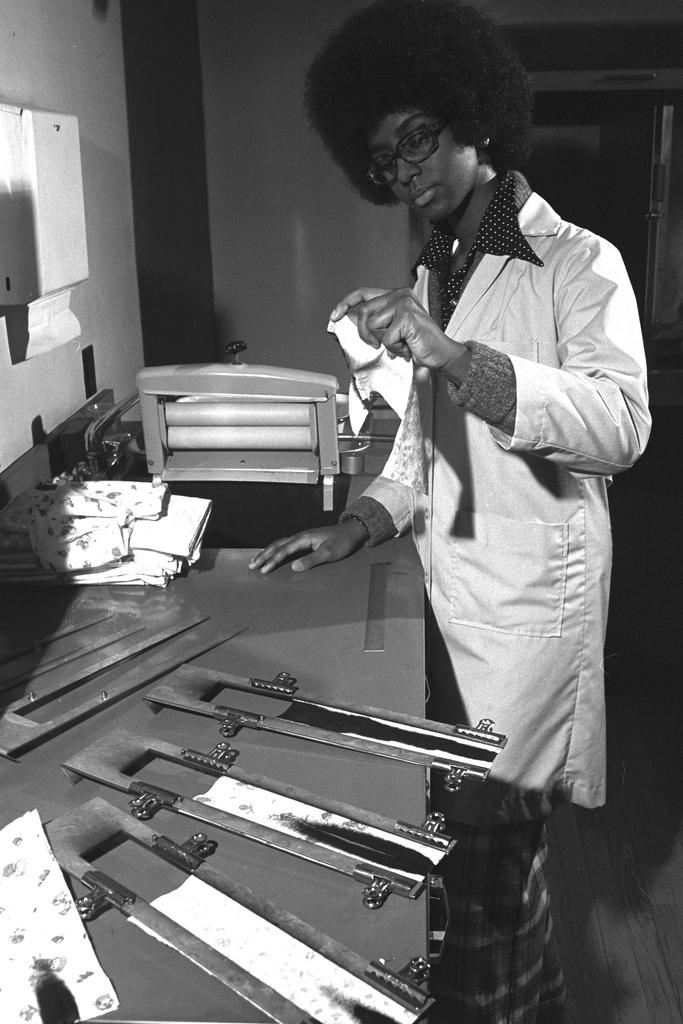

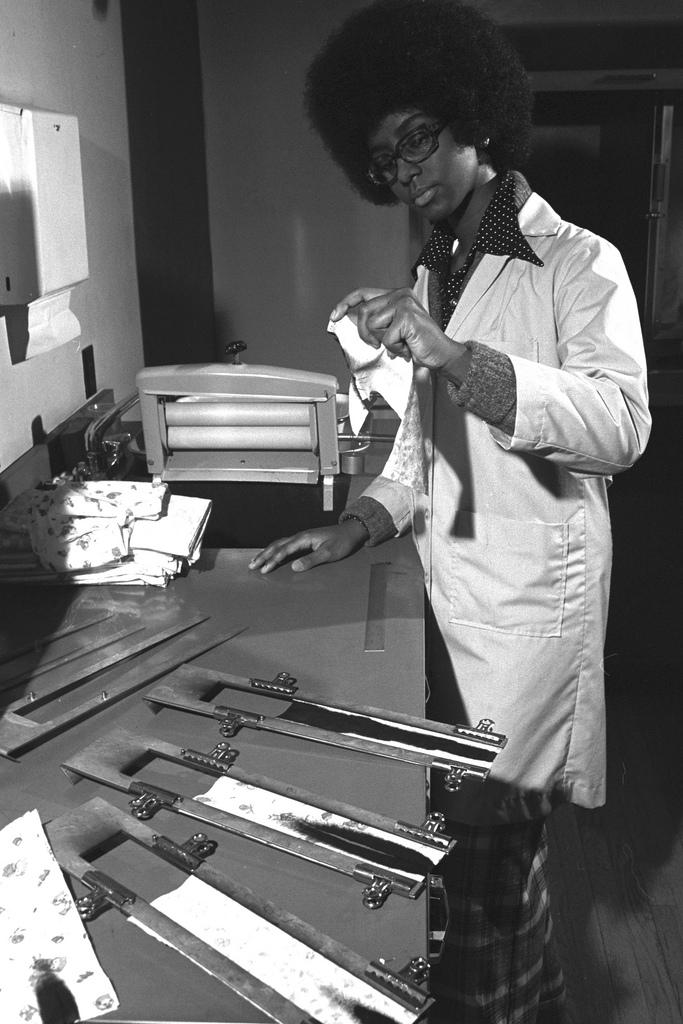

The new spray-on system, invented by Illan Kramer (pictured above) is called SprayLD. It is built from inexpensive components that are all readily available, such as airbrushes and cooling nozzles used in a steel mill (video).

The vision is that of a Ghostbusters-like team, armed with spray nozzles and wearing tanks strapped to their backs. They say that a surface the size of a car roof could provide 300 watts. That means that the roof of a house could easily provide 10 kilowatts. The entire spray apparatus can be built for less than $1,000. No word yet on how much the spray itself would cost.

The spray-on format makes it easy to apply. Now, if they can get the efficiency up and the cost of the spray down, this is something that could become extremely widespread.

Image courtesy of University of Toronto.

RP Siegel, PE, is an author, inventor and consultant. He has written for numerous publications ranging from Huffington Post to Mechanical Engineering. He and Roger Saillant co-wrote the successful eco-thriller Vapor Trails. RP, who is a regular contributor to Triple Pundit and Justmeans, sees it as his mission to help articulate and clarify the problems and challenges confronting our planet at this time, as well as the steadily emerging list of proposed solutions. His uniquely combined engineering and humanities background help to bring both global perspective and analytical detail to bear on the questions at hand.

Follow RP Siegel on Twitter.

Upsolar Promotes Energy Freedom with New Home Solar Loans

U.S. solar power installations are on track to post another year of record growth. Enough solar power capacity – 1.354 gigawatts – was installed in the U.S. in Q3 2014 to power some 3.5 million homes, according to the latest quarterly report from the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) and GTM Research.

More affordable and as emissions- and pollution-free as ever, U.S. home and property owners are installing solar photovoltaic (PV) power systems at an unprecedented pace. An industry first, more than 300 megawatts of residential PV went into operation in Q3. More than half of that was installed in states that don't offer any incentives, SEIA and GTM highlighted.

That's encouraging news for players all along the U.S. solar industry value chain, particularly in light of ongoing international trade tensions and a scheduled scaling down of the federal investment tax credit (ITC) at year-end 2016.

Facing stiff competition for residential customers, downstream solar PV finance-and-installation companies are turning to home solar loans as opposed to the third-party leases that have galvanized growth in recent years. Upsolar America believes it has a winning lifelong solution with its zero-down, 20-year, 5.99 percent fixed rate home solar loan program.

Upsolar America's Energy Freedom

Dubbed Energy Freedom, Upsolar America's turnkey home solar program removes all the hassle and worries associated with choosing, financing, installing and maintaining home PV energy systems. A better deal financially for homeowners than solar leases, Upsolar's zero-money-down home solar package enables them to own their PV systems, in contrast to solar leases, Upsolar America President Stephane Dufrenne explained in a 3p interview.

For qualified home PV installation businesses, Upsolar America's Energy Freedom offers a complete, turnkey solution that includes attractive homeowner financing and a path to ownership. The primary objective in designing and assembling the program was to create a simple, more affordable and comprehensive solution that spans the entire process of having a home PV system installed, as well as providing operations and maintenance (O&M) over the entire lifecycle, Dufrenne told 3p.

As when entering into a residential solar lease agreement, homeowners participating in Energy Freedom can claim the federal solar investment tax credit (ITC) and any state rebates and incentives. In contrast to home PV leasing, Energy Freedom participants “put equity into their homes, because they own the systems ... In that way, leasing is more like an expense, while our loan program is more like an investment,” Dufrenne said.

On the flip side, Energy Freedom offers qualified residential PV installation businesses an opportunity to expand in local markets where tough competition and market regulations already make sustained commercial success a difficult proposition, he added.

A fab-less, asset-light PV enterprise

“Fab-less” and “asset-light,” Upsolar America's China-based parent company is proving adept at building a very lean multinational business organization. This business strategy makes Upsolar nimble and confers other competitive advantages, Dufrenne elaborated.

While Upsolar designs, engineers and oversees the production, and assures the quality of its brand- name PV systems from silicon to panel and module, it does not own any manufacturing facilities. “We control the entire supply chain in accordance with strict manufacturing specs,” Dufrenne explained.

Covering its bases in light of international trade tensions and the imposition of punitive import duties, Upsolar has contracts with PV manufacturers in Mexico and Taiwan, as well as with its original contract manufacturer in China.

In addition, Upsolar maintains “a strong R&D lab for testing the quality and reliability for all components, and we procure those components ourselves, so we can take advantage of volume discounts ... It's a somewhat unique business model in PV; we're the only one to do that,” Dufrenne said.

A complete home solar solution

For Upsolar, that translates into “easy access to capacity, good and competitive pricing. We have a worldwide footprint, and we don't have to bear the burden of operational capex. We build to order, and we keep a lean inventory, which makes us very nimble compared to larger competitors,” he continued.

Similarly, Upsolar has vetted and assembled a chain of suppliers for the inverters, racks, mounts and other components that make up home solar PV systems. On Oct. 29, Upsolar announced a partnership in which APS America will supply the “advanced microinverter technology” for Upsolar America's Energy Freedom program.

Given a lifespan of at least 20 years, assuring home PV systems performance over their entire lives is a key to taking the guesswork out of PV system purchasing and safeguarding homeowners' investments. Addressing this, the Energy Freedom package includes operations and maintenance (O&M), as well as Upsolar's own PV panel and component partners' warranties. Participating Energy Freedom installers perform O&M for the first two years. NextPhase steps in from year three to year 15.

Tightly focused on local markets, Upsolar America is initially rolling out its Energy Freedom program in U.S. Sunbelt states and those where state government incentives make installing a home PV energy system that much more attractive. In the process of building a network of qualified installers, the list includes Arizona, California, Colorado and Nevada. It's also doing business south of the border in Mexico.

Installing around 250 MW per year of solar power capacity, Upsolar is operating at a much smaller scale than market-leading competitors such as SolarCity, which has rapidly grown into the U.S. residential PV market's 800-pound gorilla. That suits Upsolar just fine, Dufrenne told us.

“We're not operating at the scale of a SolarCity or Vivint, but we're recruiting a decent corps of installers. And we're helping them get up to speed – developing a credit, sales and order management platform that's completely paperless and verified by DocuSign. It's all very seamless.”

“Early response has been extremely positive, and we have enrolled a host of installers eager to expand their business with our solution,” Dufrenne said. ”Our offering will continue to improve with new features, including design services, so installers are free to concentrate on their primary tasks – selling and installing systems – rather than worrying about procurement or getting credit lines with local distributors.”

Images courtesy of Upsolar America

16 Major Companies and Agencies Say No to Chemical Flame Retardants

The debate over chemical flame retardants seems to be heating up. The Center for Environmental Health, which helped encourage a rewrite of California's regulations regarding safety standards in furniture manufacturing, announced last week that 16 major furniture manufacturers have now sworn off chemical flame retardants.

The companies, which include Facebook, Staples, Autodesk and Blue Cross Blue Sheild of Massachusetts, have pledged to stop buying furniture with chemical flame retardants in them. Several of the companies, like Staples and HDR Architecture, North America's second-largest architectural firm, are national brands.

The pledge against chemical flame retardants

The movement is in response to new California standards that allow furniture manufacturers to opt out of adding chemical flame retardants to their products. Technical Bulletin 117-2013 also changed the mechanism for determining a product's flammability risk, which in effect has encouraged furniture manufactures to expand their use of safer, sustainable and low-toxic materials.

Kaiser Permanente led the movement earlier this year with its pledge to stop buying furniture imbedded with flame retardant chemicals. Its announcement prompted a rebuke from the North America Flame Retardant Alliance (NAFRA) and the American Chemistry Council (ACC). The ACC has expressed its "concern" about the decision, stating that "flame retardants help save lives" and appealing for more discussion on the matter.

So far, however, the pull away from chemical flame retardants seems to be gaining speed, including by companies whose major markets aren't governed by California regulations. Aiding this movement are the studies that now dispute the assertion that the chemicals actually did save lives. Increased exposure to fumes by first responders who waded into house fires have helped to lay doubt to that claim. So do findings that indicate the toxins are being absorbed by people who use the flame retardant-laden furniture.

Changes spurred by new products

The 16 signers of CEH's Purchaser's Pledge go beyond private companies and include several city and county agencies, including some outside the state of California:

Public Entities

- San Francisco Department of Environment

- City of Portland, Oregon

- Multnomah County, Oregon

- Autodesk

- Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts

- Dignity Health

- Genentech

- Hackensack University Medical Center

- HDR Architecture

- Healthy Building Science

- Kaiser Permanente

- Kay Chesterfield

- One Workplace

- Perkins + Will

- Staples

Plus, the following furniture manufacturers have already removed chemical flame retardants from either all or some of their products:

Manufacturers whose lines are 100 percent CFR-free

- Andreu World

- Arcadia Contract

- Bretford

- David Edward Company

- Global/ GLOBALcare

- Humanscale

- Izzy+

- Neutral Posture

- OFS Brands

- Teknion

- Wieland

- Haworth

- Herman Miller

- Leland International/Freshcoast

- Martin Brattrud

Sustainability-Focused Innovation: Key to Growth at Alpine Waste and Recycling

By Graham Russell

Often overlooked in all the sustainability literature on risk management, internal cost savings from reduced energy or water usage, improved employee loyalty and productivity due to better working conditions, wellness programs, etc. is the concept of sustainability-focused innovation in products or services as a source of market opportunity and new revenues.

This type of externally-focused approach to sustainability as a driver of improved financial performance is just as much a part of the overall business case for corporate sustainability as these internally-focused initiatives. Few companies illustrate this market-driven sustainability approach as clearly and successfully as Alpine Waste & Recycling.

Founded in 1999 in Denver, Alpine is the largest independent waste collection and recycling company in Colorado with current revenues of $34 million and a staff of over 200. Founder and CEO John Griffith explains that, unlike many other companies with a stellar sustainability track record, Alpine’s own sustainability strategy has been shaped almost entirely by market and revenue expansion opportunities rather than by risk mitigation or internal cost-saving drivers.

Though personally a believer in the importance of sustainability, Griffith always maintained that operational efficiency and service standards needed to be the primary focuses of Alpine to insure survival in an extremely competitive industry. However, in 2006 he realized that many of his customers were beginning to demand changes in the services provided by their waste handling vendors as part of their own evolving sustainable business programs. In particular, he saw that providing services that would divert increasing proportions of their waste from landfills would create added value in customers’ eyes and additional revenue opportunities for Alpine.

Accordingly, 2007 saw the formation of subsidiary Altogether Recycling, which began with the collection of single-stream recycling material and quickly followed by building what was then only the second single-stream recycling facility in the state. It is now Colorado’s second largest recycling plant, offering customers the widest range of acceptable materials and diverting an annual volume of 72,000 tons from landfills.

Recognizing that organic material now represented the largest component of its customers’ remaining waste streams still going to landfill, later in 2007 Alpine became the first company in the Denver metro area to collect this organic material and the first to create its own organic waste processing facility. The company now processes 7,100 tons of organic waste per year for 200 customers. The collected organic material is processed into a high-quality, nutrient-rich compost which it sells to the landscaping and agricultural industries.

Griffith is the first to admit that composting has been a difficult proposition from a money-making standpoint. However, Alpine’s compost volumes are increasing steadily as more and more (especially larger) companies are recognizing the need to divert food and other organic waste from landfills as part of their broader sustainability programs. He is also confident that farmers will increasingly recognize that the quality of the compost delivered by Alpine’s plant is superior to animal waste and other traditional forms of organic fertilizer material.

In planning and implementing these first major sustainability initiatives, Alpine did not rely to any great extent on outside help from consultants, but it did pay close attention to other companies in the waste industry in California that had already implemented some of the initiatives Alpine was just starting. Once again, unlike many companies that have approached sustainability initially from the standpoint of taking cost and waste out of internal operations, Alpine has never had a Green Team, relying instead on its executive team to plan and implement these major market-focused sustainability initiatives.

The success of these first endeavors showed Griffith that Alpine could create “an identity in our marketplace as the leader in sustainability initiatives." As a result, he and his executive team began to think more broadly about other measures that could further enhance the Alpine sustainability brand.

This led to a decision in 2010 to begin conversion of the company’s fleet of trucks from diesel to compressed natural gas (CNG), making Alpine the first company in its industry in Colorado to make this transition. CNG emits 21 percent fewer greenhouse emissions than diesel, and it's also a domestically-produced fuel. Unforeseen at the time, but ultimately an added benefit to Alpine, was the substantial drop in natural gas costs over the past several years -- its cost advantage over diesel currently amounting to $1.25 per gallon. It is especially well-suited to heavy vehicles that log large annual mileages and come back each night to a central location where a refueling plant can be installed.

The incremental cost of a CNG-powered vehicle versus a diesel truck is about $30,000, and ongoing maintenance costs are somewhat higher. However, federal tax credits offset a portion of the upfront capital cost penalty.

Alpine has also has secured an unexpected labor-related benefit based on the way the CNG vehicles are refueled. Each evening the returning diesel-powered trucks must be refueled at a conventional pumping station, an operation that can take as much as 15 minutes. The CNG-powered trucks, on the other hand, are simply plugged into the “slow-fill” CNG refueling system, and the driver is immediately available to use those 15 minutes for other productive tasks. Fifteen minutes a day doesn’t sound much, but multiplied by 40+ trucks and 250 operating days a year, it amounts to a significant labor productivity benefit. Taking all of these factors into account, company CFO Alek Orloff reckons that the annual ROI on the incremental upfront capital cost is in the range of 30 to 35 percent.

Griffith points out that the truck conversion project is a deviation from the firm’s normal approach to sustainability insofar as it represents an internal initiative as opposed to one that is driven essentially by a market opportunity. The financial return on the project has in fact been adequate, but the leadership team justified the move in large part on the grounds that “it fit with who we wanted to be in the industry”: namely, the sustainability leader. Perhaps it is after all a market-driven opportunity insofar as it leverages the company’s sustainable brand image in the eyes of customers. Fifty-one percent of the company’s trucks now run on CNG.

Part 2 of this article will show how Alpine has used sustainability-focused thinking to develop a service product that is unique in the waste industry.

Latest Sustainability Assessment Tools: S-CORE and Future-Fit

By Devon Bertram

As more and more organizations are recognizing the value and need to consider sustainability as part of good business, new assessment and tracking tools are being developed to help them evaluate and measure their sustainability efforts and performance. Tackling sustainability can be an overwhelming task, and it can be difficult to know how and where to start.

Two new tools featured at this year’s International Society of Sustainability Professionals (ISSP) conference, held last month in Denver, were S-CORE from ISSP and the Future-Fit Business Benchmark from 3-D Investment Foundation and The Natural Step Canada.

S-CORE

S-CORE (Sustainability – Competency, Opportunity, Reporting and Evaluation) is a Web-based tool used to assess where and how sustainability lies within an organization, while also providing insight into opportunities based on identified sustainability goals. S-CORE is not limited to a certain business type or size, and includes almost 100 practices across various sectors that span all levels and stages of sustainability implementation.This tool can be valuable for guiding internal decision-making and supporting the development or advancement of an organization’s sustainability plan by generating new ideas, goals and priorities, assigning responsible parties, and tracking various stages of benchmarking for each practice. Once the assessment has been completed by an organization, a comprehensive report includes a gap analysis, inventory of current practices, opportunities and recommendations, resources, and an action plan.

This licensed assessment tool has been used by a range of organizations including Nike, the city of Santa Monica, Alaska Airlines, Northeast Utilities (Connecticut Light & Power) and Dartmouth College. While S-CORE was originally developed by AXIS Performance Advisors, the International Sustainable Development Foundation and the Zero-Waste Alliance, it was turned over to ISSP this year to broaden its reach and usability.

Future-Fit Business Benchmark

The Future-Fit Business Benchmark is a collaborative, science-based and open-source initiative focused on defining a business fit for the future – “one that will flourish while adding to the wellbeing of society as a whole.” The tool helps individuals quantify how actions can contribute to this vision by presenting performance criteria defined by 28 social and environmental goals and metrics within nine areas (physical resources, products and services, operational waste, land, employees, communities, customers, boards and owners, and supply chain). The tool was created with input from over 100 experts, and the first draft was released for public comment last month.

The Benchmark aims to define a fully sustainable business model, and examines what business can be within both a healthy planet and a healthy society. The tool can be used by a range of stakeholders – whether an employee at a company, a rater, an investor, a consultant, a student or a policy maker – and is created with the intention to identify the gap between the business practices of today and the needs of the future.

Currently, each of the 11 environmental and 17 social goals is presented with a consistent format that includes the context to which the goal applies, business benefits, issues mitigated, science-based design constraints, examples of companies that are succeeding in this goal, and a place for users to provide feedback. The next step in the Future-Fit tool is to develop key performance indicators (KPIs) to support businesses in measuring and managing their progress within each of these goals. Public reactions and help from experts is being solicited to support this development effort, as well as to assist in refining each of the Future-Fit goals based on the feedback received.

Overall, these internal tools respond to the increasing need for resources that can support organizations trying to integrate sustainability into their day-to-day operations and broader strategic goals. While S-CORE is more of a qualitative evaluation and Future-Fit is based mostly on metrics, both tools provide a framework for internal evaluation, goal-setting, measurement and tracking. Such internal tools can hopefully enable organizations to more easily integrate and communicate sustainability efforts across departments and management -- and perhaps support smoother and easier reporting efforts. The more accessible we can make sustainability, the more we’ll see it in practice. S-CORE and Future-Fit seem to be on the path to helping make this happen.

Image credits: 1) S-CORE 2) The Natural Step Canada

Devon Bertram is a Sustainability Manager with YR&G, a firm with offices in Denver, New York, and Chicago that provides technical and strategic sustainability consulting for buildings, communities, and corporations around the country and internationally.

The Business of Giving Back

By Debbie Fletcher

The art of philanthropy is alive and well. Even in today's financially challenging climate, many businesses are maintaining their commitment to fundraising and giving to charity; recent research conducted by the Charities Aid Foundation -- the summary of which is published here by the Guardian -- revealed that the amount donated to charity by FTSE 100 companies has risen by £1.2 billion (or around $1.9 billion) since 2007. That includes cash, volunteer hours and in-kind donations.

The same report showed that 98 percent of those 100 companies gave every year, which is perhaps a far higher figure than many of the public might expect. Evidently, there is significantly more 'good' being done in the corporate world than is being communicated publicly. The business of giving back is very much in practice.

Some of this is on a huge global scale. Hollywood acting legend Paul Newman launched Newman's Own in 1982, and after generating large profits in the company's first year, he famously declared, "Let's give it all away to those who need it." So he did. Newman's Own Foundation was established in 2005, and 100 percent of profits and royalties from the Newman's Own label were donated to charity; by 2012 the total given reached $380 million. "I want to acknowledge luck. The benevolence of it in my life and the brutality of it in the lives of others," the founder once said. Newman passed away in 2008, but his legacy continues.

Another example: The Polo Ralph Lauren Foundation supports a number of initiatives. One, the American Heroes Fund, has established a college scholarship fund for children of the victims of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Another is the Pink Pony Campaign, Ralph Lauren's worldwide initiative in the fight against cancer, with the dedicated mission to reduce disparities in cancer cure in medically-underserved communities. How that translates in the U.K. is that 25 percent of the purchase price of all Pink Pony products benefits Royal Marsden Cancer Charity.

The partnership was revealed in May 2014, with Lauren disclosing the sentiments behind the campaign in this video, published on the Vogue website. The survivor of a brain tumor, he lost a friend to breast cancer and was driven to do more. "I hate it when people call me a philanthropist," he said. "I see it more as coming from the heart, and something I do to improve the environment."

Very often personal reasons are behind such ventures. Addiction marketing firm The Drug Rehab Agency recently announced its plans to donate 10 percent of all profits to help addicts who don't have the financial means to otherwise receive quality treatment. The company was formed by Marcus Hansen, who lost his best friend, Jason Olsen, to drug use: Hansen later discovered that Olsen had been on the waiting list for a rehab facility in Phoenix. Having made the decision to try and seek help and beat his addiction, he was denied the opportunity to do so as he didn't have the financial means to quicken the process.

“After losing my friend, due to the backlog to enter into a state facility, I felt it is my job to help others that are in the same situation, as best I can,” Hansen said. “We are blessed enough to work with some of the best treatment centers in the U.S., allowing us to help people get into these facilities as often as we can.”

Clearly, this is a campaign close to the heart of the business owner -- in fact, a case study of a company created and launched to directly benefit a worthy cause. Giving something back remains rewarding and fulfilling.

Image credit: Flickr/asenat29

Debbie Fletcher is an enthusiastic, experienced writer who has written for a range of difference magazines and news publications. Follow her here: @Debbie_Fletch18.

Global demand for coal only to march higher

Global demand for coal over the next five years will continue marching higher, breaking the 9-billion-tonne level by 2019, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its just published annual Medium-Term Coal Market Report.

The report notes that despite China's efforts to moderate its coal consumption, it will still account for three-fifths of demand growth during the outlook period. Moreover, China will be joined by India, ASEAN countries and other countries in Asia as the main engines of growth in coal consumption, offsetting declines in Europe and the United States.

“We have heard many pledges and policies aimed at mitigating climate change, but over the next five years they will mostly fail to arrest the growth in coal demand,” IEA executive director Maria van der Hoeven said at the launch of the book. “Although the contribution that coal makes to energy security and access to energy is undeniable, I must emphasise once again that coal use in its current form is simply unsustainable. For this to change, we need to radically accelerate deployment of carbon capture and sequestration.”

To read the Executive Summary of the report click here.

Global Ghost Gear Initiative Aims to Clean Up the Fishing Industry

In recent years, the double-whammy of plastic trash and overfishing has drawn more attention to the plight of the world’s oceans. I was made aware of this mounting problem several years ago when I stayed at a remote beach town in northeastern Brazil. Plastic bottles, furniture and sheaths of fishnets had washed up in an area where the nearest town or city was scores of miles away. The image of those fishnets reminds me that the dangers to marine life continue even if a global moratorium on fishing kept every single boat in port.

These threats are ongoing because of fishing equipment, mostly nets, that are dumped into the oceans daily. This “ghost gear” will remain in the waters for centuries, continuing to kill marine life.

To that end, last month over 40 delegates from various organizations convened in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia, to lay the groundwork for the new Global Ghost Gear Initiative, or GGGI. This multi-stakeholder effort, which is bringing together NGOs, industry leaders and intergovernmental organizations, is focused on finding innovative solutions to the growing problem of plastic debris the fishing industry loses, abandons and discards daily. The cost in money and resources is too large to ignore: United Kingdom-based World Animal Protection estimates that over 640,000 tons of fishing gear, mostly nylon or plastic, ends up dumped in the world's oceans and seas each year.

The results are lost economic opportunity and more danger to threatened marine species as this equipment -- including nets, traps and pots -- harms and kills marine life even after fishermen decide such gear is no longer useful. Ongoing trends in the global marketplace are not helping. The disposable society in which we live leads most of us to view plastic waste in any form as worthless. Meanwhile the growing middle class worldwide is demanding more seafood, much of which is caught by independent fishermen far down the global supply chain. More NGOs are dedicated to cleaning up the oceans of this killer trash, and a few companies are collecting this trash and recycling it into new products. But as a group they are going into what is akin to a massive gunfight with the equivalent of a slingshot. The complex problem of ghost gear has many moving parts — and more cooperation is needed.

Therefore GGGI is on a quest, according to its most recent mission statement, “to create safer, cleaner oceans by collecting evidence to understand the problem of ghost fishing gear in order to drive effective and sustainable fishing on a global scale.”

Evidence, in fact, is where GGGI must start some heavy lifting. As is the case of any new global initiative, may questions fester over how this initiative is going to start. Is it outreach? Communication? Government lobbying? Partnering with business? According to many of the delegates who spent those two days in Ljubljana hammering out an agenda, the organization will have to start with gathering data. At first such a task may sound like a dry and tepid response to a pressing environmental and economic problem. The word at this conference, however, was that in order to make the case and create a sense of urgency, reliable data on how much ghost gear is floating or moored in our oceans is needed. Many of the estimates on how much ghost gear exists in the oceans, along with numbers of wildlife lost annually, are based on samples taken in a few spots around the word. Business and governments, however, will want to know more before they commit resources to this continuing problem.

Likewise, the question of how to solve the ghost gear crisis rests on how this organization will conduct outreach, and who will be held accountable. The common perception is that fishermen are creating this problem by carelessly dumping their unwanted equipment into the water. The truth, however, is much more nuanced and complicated. Tonny Wagey, senior scientist with the Indonesian government’s Ministry of Marine affairs, gave me his country's perspective during a conversation we had as the GGGI meeting wrapped up.

“Environmentally and politically, the problems are the lack of understanding, awareness and political will to deal with this,” Wagey said. “The main culprit is illegal fishing. After all, the local and small fishermen don’t want to lose their nets because they can’t afford it as they would have to pay two or three months of their wages. It is the big companies that are often responsible, especially those who are coming from outside our country to fish illegally.”

Wagey’s perspective is representative of Indonesia, the world’s fourth largest seafood producer with 4.8 million tons caught, processed and sold annually. Hence a risk GGGI confronts is the developed versus developing nations schism that is all too common. Considering the fact emerging economies such as Indonesia and Thailand are among the world’s biggest fishing producers, the challenge GGGI will find is boosting cooperation between all stakeholders in all countries. It will not be easy.

As one delegate explained to me, it is tough to come up with solid regulations and frameworks when so much of what bedevils the fishing industry is the lack of structure. Regulations, or lack thereof, are one issue; the dearth of good oceanographic charts for fishermen is another problem. A boat may be going about its daily business, only to graze a reef or rock outcropping no one knew about, even if that knowledgeable fisherman followed generations before him into this line of work. Hence one of GGGI’s biggest challenges will be convincing these companies to provide their suppliers with the tools necessary to make fishing safer and less destructive -- and take responsibility for the treating the oceans both as a resource and a garbage dump.

What is on GGGI’s side is the mounting size of the problem. I sure did not need convincing. During the second day of the conference, Aquafil, one of the main sponsors of this gathering and a nylon manufacturer that has ventured into carpet and ghost gear recycling, took me on a tour of one of its warehouses. About a 45-minute drive from Ljubljana, close to the Italian border, is a former cotton mill almost bursting at the seams with nets gathered from around the world. Bales after bales of used and discarded fishing nets — each weighing four metric tons, mind you — offered a visual that was disheartening and yet inspiring at the same time. Seeing all those stacked nets reminded me of the daunting statistics I heard over the previous 36 hours.

Some of the ideas bandied around this conference may seem too simple, yet may offer some good first steps. Color-coding nets for easy identification could be a way to identify wayward fishing companies, and of course, tagging nets to make their identity more seamless is an option, too. Collection spots for nets in heavily-trafficked fisheries are a start; meanwhile, more aggressive education programs cannot be overlooked. Better design always leads to more sustainable solutions, and of course technology, from maps from a company such as Google, as well as apps, can help stall the mess we are making of our oceans.

In the end, if industry -- including the commercial suppliers, processors and retailers -- becomes involved, GGGI will score a fast start. In an age where a “tell all” video timely posted online can cause a company gigantic headaches, no business wants to be embarrassed — or lose customers who over time are more interested in where their food is sourced. The time to start on this problem, sadly, was yesterday: But based on the cooperation and ideas I saw coming out of Ljubljana, GGGI is on its way -- which in the long run will save an industry that at the moment is sabotaging itself by only looking at short term profits.

Image credit: Aquafil, Dutch Shark Society, Leon Kaye

Disclosure: Aquafil covered the travel costs associated with my attendance at the GGGI conference.

The Street Store: A Lesson for the Sharing Economy?

We’ve seen a lot of charities emerge into the global spotlight in recent years. Organizations like Doctors Without Borders, World Wildlife Fund and Defenders of Wildlife have gained prominence as world events shaped the demand for their services. But most of these organizations have been around for years, and their global reach and international reputation are largely the result of hard work, promotion and donor investment.

One nonprofit that began in South Africa, however, seems to be setting a new bar when it comes to the amount of time it’s taken to gain brand recognition.

The Street Store, born on the streets of Cape Town in January of this year, began as a local initiative by Max Pazak and Kayli Levitan. The founders, with the support of South African advertising agency M&C Saatchi Abel and the Haven Night Shelter, wanted to find a way to streamline donations to the homeless. They also wanted to reduce the awkward and often humiliating emotional exposure that charity recipients are often subject to when receiving aid. So, they came up with a way in which recipients could pick out what they needed personally without combing through boxes of miss-sorted clothes, or be forced to take things they didn't need.

And, just as importantly, they brought the store to the community members, rather than making the members travel long distances to ask for help. By developing a simple, easy-to-reproduce sign that could be printed out by anyone and could accompany the hangers and displays of shoes, clothes and donated materials, they set up " shop" along the side of the street and invited local residents to come in and browse.

But it is what happened after the Street Store's pop-up shop began to take off that's interesting: In an effort to gain donations and funding for its launch, the founders turned to the Web. According to the Street Store's website, the response was momentous. Not only did the nonprofit succeed in raising far more than expected (more than $2 million), but it garnered the publicity of international organizations like One, TED and Huffington Post that pledged to help to globalize the initiative.

A year later, dozens of Street Store events have taken place throughout the world. The locations range from South Africa to South America, as well as the United States, Canada and Belgium. Some of the world's largest cities have been hosts to pop-up stores, with donations ranging from drinking water to isles of free clothes, winter coats and shoes.

Its global success begs a question about the way that charity is distributed, the way it is perceived, and the remarkably simple way that this initiative, which spawned dozens of home-based exchanges, is accomplishing its goal: What is it that makes it work? Is it the simplicity and lack of investment required to set up the pop-up store? Is it the universality of the idea, the fact that it works in just about any private or commercial venue? Or is it the personal connection people feel to their communities and neighbors at need?

There's a Jewish saying that suggests that the highest form of charity is one in which the donor and the recipient are not known to each other. At the heart of that thoughtful concept is the dignity of the recipient, who benefits but isn't expected to either repay or feel beholden to the giver.

The Street Store seems to work because it reaches its goal simply and straight-forwardly, and because its ultimate product is the self-esteem and self-worth that's gained by both parties. It takes a page from the early days of the sharing economy when sharing your neighbor's drill or lending out a bicycle was the sum of the act, and where community action was the intended product, not the commercial outcome. It's a lesson that may have great value as we move into the new year, and it's encouraging to know it's an attitude that still thrives where it counts most.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QDw0JtwQU8A

Image credit: The Street Store

Berkshire Hathaway’s Citizenship: Culture, Scale and the Future

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from the new book, "Berkshire Beyond Buffett: The Enduring Value of Values," by Lawrence A. Cunningham.

By Lawrence A. Cunningham

The companies owned by Berkshire Hathaway, the huge conglomerate that Warren Buffett built, follow their leader in embracing corporate social responsibility, stewardship and sustainability. But the breadth and scale of the sprawling conglomerate can hide both the commitments and periodic problems.

For example, in the early 2000s, before it became part of Berkshire Hathaway, Russell Corp. signed major licensing agreements to produce sportswear adorned with popular logos. It made contracts with scores of U.S. universities and signed a large deal with the National Basketball Association.

The trouble was, the goods affixed with licensed Russell logos were made in factories in China and Honduras that engaged in objectionable conduct. In China, the company’s products were manufactured in sweatshops that violated principles of international human rights; in Honduras, company officials boarded up the plant and ousted the workforce in retaliation for attempts to unionize. Such misbehavior drew the attention of activists across the United States, including a group of college students who demanded that universities terminate the licensing agreements.

These problems persisted, however, even after 2006 when Russell was acquired by Fruit of the Loom, which had become part of Berkshire in 2002. Ultimately, in 2009, a former employee of the Honduras facility took the floor at the Berkshire annual meeting to report on the conditions and demand a response. Russell’s operating activities contrasted with Berkshire’s tenets of integrity and repute; promptly upon learning of the problems, Fruit of the Loom corrected them.

This case highlights the challenges Buffett’s successor will face in overseeing the sprawling array of operations. It illustrates the downside of corporate decentralization. When it comes to potential subsidiary violations of company policy or law, information must reach Berkshire headquarters immediately. But the existing framework is informal. It is based heavily on the mandate of subsidiary managers: Report bad news early. In the distinctive context of Berkshire culture, steeped in integrity, such an approach may be satisfactory. In the spirit of autonomy, it is essential.

But many give Berkshire a pass on certain matters because of Buffett’s presence. His eventual absence will remove this benefit of the doubt. Successors will need to assure both continuity and reliability. Surprises could result in government authorities imposing more radical, less desirable changes, if Berkshire has to contain a controversy, rather than be in front of it. The Russell episode is both an exception to Berkshire’s norm and a reason to consider formal oversight of its subsidiaries.

While Berkshire has won plaudits for good corporate citizenship, critics complain about the absence of conglomerate-wide reporting on items such as social responsibility and sustainability. Many Berkshire subsidiaries — including Brooks, Johns Manville, Lubrizol and Shaw — are in the vanguard of such corporate stewardship. They join elite global companies in the practice of issuing formal responsibility and sustainability statements and audited reports on the corporate treatment of stakeholders, especially employees at home and abroad, and of the environment.

Berkshire is unusual in that its structure does not lend itself to issuing a formal corporate report at the parent level. And the number and size of Berkshire’s subsidiaries can obscure some of their internal measurement and reporting efforts. Critics urge consolidated policies, including a conglomerate statement of responsibility or charter of sustainability. It may unduly interfere with subsidiary autonomy to set corporate-level policy, but a consolidated report will prove valuable in order to highlight the varying ways that Berkshire subsidiaries embrace stewardship—and assure continued adherence.

Shaw Industries, for example, led the carpet industry to newfound appreciation for its responsibility concerning environmental protection and sustainable development. During the 1990s, people began to realize the environmental costs of using non-biodegradable artificial fibers to make carpets; disposing of them presented a significant waste management problem. Shaw then started to promote carpet recycling programs. It began to produce synthetic yarn sourced from recycled plastics such as soda bottles and developed a polyolefin backing material that cut raw material use in half.

McLane embraces a “green advantage initiative” to manage its fleet of trucks that stock America’s supermarkets. The initiative stresses reducing environmental impact and increasing operational efficiency. Efforts include improving gas mileage by lowering truck highway speeds and recycling thousands of gallons of water used to wash produce. McLane installed $7 million of efficient lighting in its distribution centers and invested $100 million in automation scheduling technologies to plan truck shipments, reducing the cost and impact of its fleet.

Acme Brick makes an ecological product: bricks of earthen clay. The bricks provide efficient insulation, thereby reducing energy usage and costs. Since its founding in 1891, Acme has built plants near distribution destinations — an idea codified in today’s environment design protocols that define a five-hundred-mile radius. Recycling incorporates scrap clay and sawdust into the brick. Reclamation programs create wetlands for wildlife and plant whole forests on former production sites. Acme Brick has won numerous industry awards for its environmental stewardship.

Concerning employees, finally, Brooks, like many apparel, footwear and sporting equipment makers, remembers the furor that engulfed Nike, Inc. in the late 1990s and early 2000s when customers learned of abusive labor practices in its Asian factories. They boycotted Nike products in protest, and the company reformed. Many factors contributed to Nike’s transgressions, including relentless cost pressures in its competitive markets. The price of athletic footwear declined rapidly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and Nike competed by finding the cheapest ways to make shoes, which included inhumane labor practices.

Brooks avoided this vise thanks to a business model focused on a premium brand at premium prices, a piece of equipment for the serious runner, selling higher-priced shoes in specialty stores. Brooks is not the low-cost producer in its industry, and its overseas factories are not the low-cost factories. As chief executive officer, Jim Weber explained in an interview for this book, his customers value the company’s investment in such responsible behavior.

Retaining subsidiary autonomy at Berkshire is important, both as a cultural matter and because the needs of the businesses vary so greatly. For example, jewelry companies focus on the ethical mining of minerals; home furnishing companies on preserving forests; transportation companies on reducing fuel usage and emissions; energy companies on targeting renewable sources. For some companies, priority rivets on internal operations, whereas others look to the supply chain; for some the concern is employee safety while others attend to a particular customer type. At the same time, it may be valuable for Berkshire as a group to collect and publicize results.

The need for internal control systems and consolidated reporting will likely increase as Berkshire expands into the international arena. A few subsidiaries boast major global operations, especially ISCAR/IMC, as well as Gen Re, Lubrizol and MiTek. Others have important overseas operations, including CTB, Dairy Queen, FlightSafety, Justin, Larson-Juhl and MidAmerican Energy. A majority of the companies have at least some operations in Canada and Mexico (e.g., Benjamin Moore, Fruit of the Loom, Johns Manville and the Marmon Group), and many manufacturing companies own or operate facilities in Asia (e.g., Brooks and TTI). Yet until its acquisition of ISCAR/IMC, begun in 2006 and completed in 2013, Berkshire had acquired only American companies.

Given globalization, it will be inviting to enlarge Berkshire’s acquisition universe. The timing may be propitious, as the accumulation and flow of intergenerational family wealth that occurred in the United States during Berkshire’s early decades is recurring across Asia and Latin America. But when going global, the need for centralized internal control and conglomerate reporting will intensify.

Image credit: Flickr/x1brett

Lawrence Cunningham, a corporate law professor at George Washington University and long-time editor of The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America, is the author of the new book, Berkshire Beyond Buffett: The Enduring Value of Values, from which the foregoing is adapted.