Bottle Refill Schemes Work in Other Countries, So Why Not the U.S.?

A returnable Coca-Cola bottle sold in Mexico. (Image courtesy of the author)

This story is part of a new solutions journalism series focused on refillable packaging, how refillables are used around the world, and what's holding these systems back from scaling further. Follow along with the series here.

You'll likely notice something different when you order a Corona in Mexico — and we're not just talking about the taste. If you look closely at the label, more often than not you'll see it's a little faded, evidence of the container being washed and reused dozens of times. Return and refill systems like this are prevalent across Latin America and around the world, and not just for beer. The world's largest soft drink companies, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, sell billions of units in refillable plastic bottles every year across Latin America, Asia, Africa and Europe.

To people in other markets, the news that major bottled beverage brands — among the largest producers of single-use plastic globally — are already operating successful refill systems may come as a surprise. "The refillable bottle is a very common packaging type, but one of the reasons why it's not as visible is that it's not present in the U.S. and the U.K.," said Matt Littlejohn, who leads the refillables program as part of his role as SVP of strategic initiatives at the ocean conservation nonprofit Oceana.

About 14 percent of Coca-Cola's global beverage sales were sold in refillable bottles last year. PepsiCo is around 10 percent. And major beer companies like Heineken and AB InBev, which owns Corona, sell upwards of 30 percent of all products in refillable containers globally, Littlejohn said. So, why don't these companies talk about refill more, and why aren't they selling them in the U.S.?

How do refillable bottle programs work?

From Mexico to Chile, Germany to the Philippines, millions of people around the world see bottle return and refill as commonplace. But for the uninitiated, it may sound confusing at first. How does that even work? Really, it's pretty simple.

When people head to their local corner store, they'll see drinks in refillable containers alongside those in single-use bottles. In Mexico, for example, most bottled beers distributed by Grupo Modelo — including Corona, Modelo and Victoria, among others — can be refilled. Customers simply bring their empties back, leave them in a designated place in the store, and pick up new beers for about 15 percent less than what they'd pay if they didn't return the packaging. When the Modelo truck arrives at the store with a new beer delivery, the driver takes the empties back to the bottling plant to be washed, refilled and used again.

Soda and water brands owned by companies like Coca-Cola and PepsiCo have separate containers that are marked as returnable, which are made from a more durable plastic than what's used for single-use. Otherwise, the system is the same: Customers bring their empty returnable bottles back to the store and choose a new product from the shelf.

In Latin America, Coca-Cola products cost up to 25 percent less for customers returning a refillable bottle, said Andres Wainer, chief financial officer of Embotelladora Andina, a major Coca-Cola bottler in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Paraguay. Around 30 percent of all the soft drinks Andina sells are in refillable containers, Wainer said at a panel discussion hosted by Oceana and HSBC last year. In some markets, such as Argentina and Paraguay, it's even higher — around half of all products sold.

In short: These systems are working, and not just in Latin America. Around half of Coca-Cola's volume in the Philippines is sold in refillable containers, and similar systems are thriving in European countries like Germany, Spain and France, Littlejohn said.

Each refillable container displaces dozens of single-use bottles, reducing the burden on waste processors around the world as well as the chance for packaging to end up as litter in the environment. Durable plastic bottles can be reused around 25 times, and glass bottles can be refilled 50 times or more, according to Oceana.

Returnable bottles also come with a substantially lower carbon footprint compared to single-use, even taking into account transportation and the water and energy needed for wash and refill. Coca-Cola claims its refillable bottle comes with 47 percent less lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, and Wainer said he's seen estimates as high as 90 percent for some systems.

So, why aren't brands using refillables in the U.S.?

"Really there are two things holding this back from coming to the U.S.," Littlejohn said. "The main thing is money. It's expensive. You actually have to invest."

Bottling plants are typically constructed to move in one direction — sanitizing new bottles, filling them up and sending them out to be sold. Introducing new equipment to process and clean refillable bottles can be costly. Arca Continental, a major bottler in Mexico and Ecuador that accounts for around 12 percent of Coca-Cola's annual refillable sales, says about 20 percent of its capital expenditures go toward the refill system, Littlejohn said.

Though the price-tag on transitioning a bottling plant to process refillables can be in the billions of dollars, it's not insurmountable considering the size and scale of these companies, Littlejohn told us. And he pointed to a straightforward solution: green bonds, sums of money raised from investors that are specifically earmarked for environmental projects.

While many consumer goods companies have issued green bonds, most have gone to purchase recycled plastic or support plastic recycling initiatives. Leveraging those instruments to support refill can help companies cover the upfront cost until the systems are up and running, Littlejohn said. "And it’s an asset," he told us. "You're investing in trucks and bottles and machines. These are depreciable assets. [Bottlers] book the deposits as a revenue source. This is in line with your business. Yes, you have to invest, but you get the money back and there's money for it."

Along with cost, the second challenge hinges on the way companies communicate about refill, which is somewhat curious considering we're talking about firms like Coke and Pepsi that have used the magic of marketing to stay relevant for over a century.

In places like Asia and Latin America, refillables are primarily marketed as a way for customers to save money. In his conversations with leaders at major brands, Littlejohn found that many seem convinced this angle won't work in places like the U.S., particularly as inflation stabilizes.

But even in markets where brands sell reusables on cost, field research from Oceana indicates people can and do recognize the environmental benefit of choosing reusable (check out the video above).

"This is a way to save money. They could sell that asset in the U.S. They think they can't, but they could," Littlejohn said. "And then in addition, they need to market the environmental benefit of this. The only place they sell it on the environmental benefit is in Germany."

Turning the corner on the rise of refillables

While refillables are already working in major markets around the world, they're highly under-leveraged and ready to scale, Littlejohn said. Doing so can come with major environmental benefits: Along with reducing lifecycle carbon emissions, every 10 percent increase in refillable bottle use across coastal countries could yield a 22 percent reduction in plastic bottle pollution in the world's oceans, Oceana estimates.

Brands say they're ready to be part of the transition. Coca-Cola, for example, aims to increase its sales in refillable containers from 14 percent today to 25 percent by 2030. But they have a long way to go when it comes to raising awareness and getting more bottlers and distributors around the world involved.

"They should be telling people about this," Littlejohn said of brands like Coke and Pepsi. "They’re doing this at such a huge level, and no one really knows it."

In a small sign of change, Arca Continental, Coca-Cola's primary bottler in Mexico, also serves Texas and started rolling out refillables in select markets last year. After a successful 2022 pilot in El Paso — the first time Coca-Cola used refillable containers in the U.S. in over a decade — Arca expanded the program to San Antonio this year.

"This is a direction that I think generally a lot of consumer branded companies are going to have to move in, because they're going to have to deal with the waste issue, and this is a way you can do it," Littlejohn said. "It's a simple thing, but it is such a radical simple idea, because it's not single-use."

Green Chemistry is Growing Up and Branching Out

Air Company's carbon conversion reactor, which turns captured carbon into consumer products like perfume, vodka and hand sanitizer. (Image: Air Company)

The global petrochemical industry continues to expand, adding to concerns that oil, gas, and coal are being consumed at an unsustainable level. Meanwhile, the green chemistry movement has already begun to introduce bio-based plastics, cleansers and other familiar consumer products that don't require fossil fuel feedstocks. Now, a new round of green chemistry innovation is going beyond common household products to decarbonize industrial processes, supply chains and fuels.

Petrochemicals are growing

Fossil fuels are not only used for heat and energy, but also as the building blocks for plastics, chemicals and more. The field of petrochemicals includes compounds made from natural gas as well as petroleum. In some countries, notably China, coal is also used as a chemical building block.

Common household petrochemical products include synthetic fabrics, rubber and detergents, in addition to a wide range of fuels and plastic items.

Plastics are often cited as the main driver of petrochemical growth and pollution. New research by the firm Emergen, though, indicates that global automotive and pharmaceutical sectors have also become powerful growth factors.

“Petrochemicals are set to account for more than a third of the growth in world oil demand to 2030 and nearly half the growth to 2050,” the International Energy Agency warned in a widely cited 2018 report, which also forecast a rise in petrochemical demand for natural gas.

Similarly, Fortune Business Insights predicts the global petrochemicals market will experience strong growth in the coming years, reaching $886 billion by 2030, compared to around $628 billion today.

Spotlight on sustainability

Notwithstanding this activity, signs of change are emerging. Rachel Carson’s influential 1962 book "Silent Spring" motivated new generations of 20th-century chemists to focus on sustainability. Those efforts culminated in the 12 principles for harm reduction outlined in the 1998 book "Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice" by John Warner and Paul Anastas.

The book did not stop the petrochemical industry, but it did lay the groundwork for change. "Green Chemistry" continues to guide the field today, and its full effect is beginning to emerge with new advances in molecular science.

The new wave of green chemistry replicates photosynthesis, the natural process by which plants create new molecules from carbon dioxide.

“We’re accelerating it and doing it in real time,” said Mahlet Garedew, innovation program manager at the Brooklyn-based chemistry startup Air Company. “Why don’t we start assembling these molecules at the molecular level and mimicking what nature is doing? This is the core of green chemistry. It’s the design of products and processes. That’s why this technology is exciting.”

The molecular approach is reflected in the six winners of the 2023 Green Chemistry Challenge, a program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Among the awardees is the Texas firm Solugen. The company’s proprietary “Bioforge” enzyme-based platform reassembles sugars, air and carbon dioxide into plastics, construction materials and other products. The New Jersey company Modern Meadow's bio-based protein foam replaces petrochemical dyes, reducing water use by 95 percent and energy consumption by 75 percent.

The follow-on health and safety benefits of green chemistry are also illustrated by an award to the Georgia firm Captis Aire. The company captures compounds called terpenes from wood processing facilities and converts them to biofuels, fragrances and other products. “Currently these terpenes can be an air pollutant, an irritant to eyes, lungs and skin, and are commonly burned as waste which releases greenhouse gases,” the EPA notes.

Starting the recarbonization conversation: A new biofuel made from biofuel emissions

Air Company was also included among the 2023 awardees for its trademarked “AirMade System” that recombines carbon dioxide and water into new forms. The award underscores how green chemistry can help support other elements of the bioeconomy.

The company launched in 2017 with two signature products, a vodka and a perfume, made with carbon from ethanol fermentation plants. The launch helped raise awareness about green chemistry's potential to impact a wide variety of industries, Garedew said. The company also produced hand sanitizer during the COVID-19 pandemic and even worked with NASA to convert carbon dioxide into sugars, with the aim of one day synthesizing food in space.

In the area of ethanol and biofuels alone, the potential for green chemistry is vast. U.S. ethanol producers, for example, are depending on new carbon capture and sequestration projects to cut their carbon footprint. However, new pipelines and sequestration proposals are encountering roadblocks, including the cancellation of a proposed 1,300-mile carbon pipeline for the U.S. Midwest.

A new McKinsey report also indicates that capture and sequestration is not an effective pathway to net zero. McKinsey advocates for a “recarbonization” of the biofuels and chemistry industries, using biomass and carbon from the atmosphere instead of fossil sources.

The AirMade System meets the recarbonization standard while raising the potential to avoid new pipelines. The modular, transportable system can be located at or near the point of carbon emissions. The system also includes water-sourced green hydrogen technology, powered by renewable energy.

This distributed-by-design business model eliminates the need for a centralized carbon sequestration facility. It creates the potential to deploy existing pipeline, road and rail infrastructure, and it enables ethanol producers to generate additional fuel from the same amount of biomass.

The company can use a variety of industrial emissions for carbon, but its main focus is currently on fuel from ethanol plant emissions and other bio-based sources. “Really the big impact is in chemistry and fuel industries, specifically aviation,” Garedew said.

More pressure on petrochemicals

Pressure on the petrochemical industry is beginning to rise from other sources. One example is the Beyond Petrochemicals initiative, launched in 2022 by Bloomberg Philanthropies and aimed at stopping the construction of new petrochemical plants in the U.S.

Academic resources are also gathering force. The new Center for Green Chemistry and Green Engineering at Yale University, for example, is a partnership with the United Nations to introduce green chemistry in key industries around the world, beginning with the replacement of hazardous materials in the textile and construction sectors.

The trade association American Chemistry Society co-sponsors the EPA's Green Chemistry program as part of its support for an industry-wide pivot away from petrochemicals and other hazardous materials. In contrast to past practice, the group now encourages its members to create “a new reality for chemistry and engineering” based on pollution prevention, waste reduction, resource preservation, and energy conservation.

Next steps for green chemistry

The rising uproar over the toxic impacts of the “forever” chemical group PFAS indicates the American Chemistry Society has a lot of ground to make up. The field of green chemistry itself is also evolving, as advocates for the “sustainable chemistry” movement press for the inclusion of more holistic, long-term ecological goals.

Above all, chemists themselves are emerging as powerful change makers.

“By training I’m a biosystems engineer, and I worked in an organic chemistry lab on the bio-based side of green chemistry,” Garedew explains. “A lot of my Ph.D. work was promoting that, and thinking where we can implement the principles of green chemistry.”

“Innovation is always on the horizon,” she says. “There are so many things we can do with carbon dioxide.”

Racial Bias in the Home Appraisal Process: A Hidden Barrier to Generational Wealth Through Homeownership

(Image: Aldeca Productions/Adobe Stock)

This story is part of Equalizing Wealth, a guest-contributed column that takes a sharp look at the interconnected factors driving racial wealth disparities in the United States — and puts forward evidence-based ways to address them. If you're interested in contributing your perspective to this column, please get in touch with us here.

Last year, Drs. Nathan Connolly and Shani Mott, a Black couple from Baltimore, Maryland, sought out a home appraisal to refinance their mortgage, and their home was estimated at $472,00. Recognizing the valuation was out of line with homes in the area, the couple removed any traces of their race, including family photos and books by Black authors. The pair then outfitted the home with generic artwork, white family photos and asked a white colleague to pretend to own the home. After conducting this social experiment in racial bias, their second appraiser estimated the home value to be $750,000.

Drs. Connolly and Mott believe the initial appraisal process used subjective criteria to evaluate their home, including proximity to a majority-Black neighborhood and proximity to a busy street. The couple tried to challenge the appraisal with their initial lender but were met with silence.

On the other side of the country in San Francisco, California, another Black couple, Paul Austin and Tenisha Tate-Austin, sought out an appraiser to refinance their mortgage to pay for major upgrades. The initial appraiser valued the home at $995,000. What’s most shocking is that approximately a year earlier, the home was appraised for $1.45 million. Fortunately for the Austins, when they challenged their home appraisal, the lender agreed that the appraisal's subjective criteria were “incorrect or inappropriate.” Like Drs. Connolly and Mott, the Austins removed items hinting at their racial identity, including family photos and hair care products, and also asked a white friend to pose as the homeowner. The second appraiser valued their home at $1,482,500, higher than the previous two estimations.

Both scenarios illustrate the negative systemic conditions families of color often face during the homeownership process. These conditions contribute to our racial wealth divide. Whether a person is selling or buying their home, appealing a property tax assessment, applying for a home equity line of credit, or refinancing a loan, a home appraisal is necessary to ensure a home’s value is accurately assessed.

Home appraisals play a key role in setting a foundation for generational wealth, offering the homeowner access to the full equity when they pay off their mortgage.

Home appraisers are intended to give an “independent, objective, and unbiased opinion of the estimated market value of a residential property” based on home condition, size, amenities and upgrades, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). While home appraisals should be a race-neutral process at face value, racial bias is still alarmingly present in the home appraisal process, and these two stories are not anomalies.

A 2022 Fannie Mae study looked at 1.8 million appraisals for refinance applications in 2019-2020, and researchers found that white-owned homes were valued at higher rates in all neighborhoods but especially those in majority-Black neighborhoods. The researchers concluded that the overvaluation resulted in a 10 percent higher appraisal value in their automated valuation models.

To address the racial bias in the appraisal process, the Joe Biden administration commissioned the Interagency Task Force on Property Appraisal and Valuation Equity (PAVE), a group of 13 key agencies that have an impact on the appraisal process, to create an Action Plan. The PAVE task force was inspired by U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters' (D-Calif.) plea to protect consumers in the appraisal process through letters to the Biden administration and her subsequent bill, House Resolution 2553.

With homeownership as the primary way for most people to build wealth, racial bias in the home appraisal process can contribute to the divide between wealth for white families and that of their Black and Brown peers.

White households hold 11 times more wealth than Black households and nearly six times more wealth than Latinx households, according to Prosperity Now's State of Household Wealth and the Racial Wealth Gap in 2020 report. In fact, the PAVE report notes that the “financial returns associated with owning a home” is “perhaps [one of] the biggest drivers of the racial and ethnic wealth divide." If advocates are committed to eliminating racial inequities in wealth building, we must also be committed to disrupting the barriers that devalue home prices because of race.

The PAVE task force devised five key recommendations that aim to create equity in the home appraisal process through arming consumers with knowledge to identify appraisal bias and how to combat it, diversifying the appraisal workforce, providing better data and research on bias and how to identify it, and reevaluating policies and guidance to ensure that bias is eliminated from the process.

The PAVE task force’s recommendations are extremely robust and a major step in the right direction to ensure that Black and Brown families have equal access to homeownership. Although they get to the root of the deficiencies in processes among the relevant federal agencies, which should lead to better safeguards for homebuyers and homeowners, states still have a role to play in protecting homeowners from racial bias. In 2021, California passed Assembly Bill 948 that provides homeowners and home buyers with information about contesting the appraisal process if they suspect racial bias, modifies the appraiser licensing course to include cultural competency and bias courses, and directs the California Bureau of Real Estate Appraisers to present an assessment of appraisal complaints to relevant state lawmakers.

States also have great flexibility to rethink their requirements for aspiring appraisers, including modifying or eliminating education or experience requirements to allow for a more equitable workforce.

For instance, states can innovate through partnerships with state universities and state agencies to create intentional pathways into the industry through bachelor’s degree programs. They could offer programs that help aspiring appraisers meet education and experience requirements, host appraiser mentorships, or provide stipends so that those who cannot afford to train in an unpaid capacity can still obtain the necessary experience.

It is an all-hands-on-deck responsibility to ensure that racial bias is eliminated from the appraisal process in pursuit of greater wealth equity. Consumers and advocates can also play a role in ensuring that the recommendations are being implemented in their states and that key improvements, such as incentivizing current appraisers to train up-and-coming appraisers, are funded each year.

Abandoned Coal Mines Are Home to Surprising Biodiversity

Foliage grows over the site of an abandoned coal mine in Tennessee, which was staffed by prison laborers from the late 1800s until 1969. (Image: Jacob Ian Wall/Flickr)

"This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist's weekly newsletter here."

Stripping coal from a mountain demands a wholesale rearrangement of its summit and the transformation of the surrounding forest into a moonscape. Enormous machines rip out the vegetation first, followed by the topsoil, and finally a layer or two of rock. It all becomes waste, dumped into a valley below the site. The federal Surface Mining Reclamation Act of 1977 requires coal companies to leave the denuded land in roughly the shape they found it or restore it to “higher and better use” at their expense, though many of them find ways to slip out of the obligation.

It’s hard to know how much unreclaimed and partially reclaimed mine land exists, though some place the figure at 633,000 acres across Appalachia. As many as 100,000 of them may lie in Virginia alone. Much of this land is a quagmire of erosion, water pollution, and other problems, yet some of it is slowly being taken back by the forest. It may be ill, but it certainly is not dead, and is in many cases surprisingly alive, as scientists have found over decades of studying the reforestation and recovery of mined lands.

A manual, written in September by a coalition of southwestern Virginia scientists and advocates of sustainable development, used new and existing findings to shape a vision for these ravaged landscapes.

Flat land is hard to come by in the mountainous central Appalachian region, and much of the development has occurred on ridges flattened by coal strip mines. These sites, often deemed empty space at best and wastelands at worst, have been targeted for everything from prisons, Walmarts, and industrial parks to lavender farms, wildlife preserves, and, most recently, clean energy projects. As millions in public and private investment, boosted by the bipartisan infrastructure law, pour into the region, many people are eyeing these abandoned sites.

The researchers of the High Knob Regional Initiative want them to slow down and take a look at what’s already there.

“Some of these sites, especially the older sites, have begun to restore themselves in a way where forests started to come in, and wildlife is coming into some of the sites on their own,” said Wally Smith, a biologist at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise and the team’s leader. “We’re increasingly finding that it’s not true that these are just ecological voids where nothing is living there.”

For decades, researchers, including some affiliated with the Initiative, have studied a variety of mine lands, from underground shafts to decades-old strip mines to more recently leveled sites, some overgrown with forest, others bearing nothing but stubby autumn olives (a non-native shrub) and scraggly grasses. Not only has the natural world crept back into many of these places, but so too has a multiplicity of flora and fauna, including rare and endangered species. The green salamander, currently under consideration for inclusion on the federal endangered species list, turned up in several locations in Wise County, Virginia, for instance. On another site, mined three or four decades ago, Smith’s team found mammalian diversity higher than in some parts of the surrounding forest, especially where wetlands had formed or been constructed.

Previous research has suggested wetlands and forest can be an integral part of surface mine reclamation, filtering out acidic drainage, heavy metals, and other contaminants that can seep from mine sites for years or even decades. In some cases these marshy areas formed as a result of the changes to the landscape.

Smith hopes local leaders use the region’s current moment of energy and economic transition to correct, rather than exacerbate, land use mistakes of the past. Poorly planned construction can easily erase this progress, as seen with Spearhead Trails, a vast and controversial network of ATV paths sprawled over reforested former mine land, owned by the Nature Conservancy, in southwestern Virginia. An investigation by the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism found that erosion and dust tore up creek beds, damaged homes and family cemeteries, and caused flooding.

Many people, Smith feels, see mine lands as real estate, already lost and as good as trash. He pointed to a feasibility study an engineering company filed with Virginia’s department of energy in support of a small modular nuclear reactor slated for a former strip mine in southwest Virginia. The document finds “there are few environmental restrictions regarding the preservation of the existing environment” and that a reactor fits the description of a “higher and better use.”

“The environmental considerations that you would normally consider for something like an intact forest are not there,” Smith said. “They’re kind of these guilt-free development sites.”

Smith stresses that his team isn’t arguing against development, but rather, in favor of sustainable development that brings underserved members of the impacted communities into planning processes earlier and more often than currently required. The coal industry ran rampant over the region’s mountaintops and privatized huge swathes of land for profit, and the researchers say now is a chance to try a more ecologically sound, community-centered approach.

To that end, the High Knob Regional Initiative compiled its years of research into a set of best-use recommendations for the region’s former mine lands. The guidelines target recreational development, energy development, and other construction projects, and urge developers and local officials to incorporate more environmental assessment, transparency, and public input into planning efforts, which should consider the possible effects on local communities.

“You really got this very big, maybe a kaleidoscope is the best way to say [it], with all these properties that had been mined and managed in different ways,” Smith said. “What that really means is there’s not a one-size-fits-all conclusion that you can reach about the impacts for wildlife and native ecosystems there.”

There’s also a real sense of wanting to reclaim these lands not only for the ecosystem, but also for the human communities that live there. Corporations that benefited from coal’s glory days may continue to profit from using the region’s land in other ways, even if they’re less environmentally destructive than before. For instance, the mine lands of several Appalachian states are becoming utility-scale solar fields. One of them near Wise, Virginia, is owned by Dominion Energy, which profited heartily from Virginia’s resources through gas and coal.

Tarah Kesterson, communications director for Virginia’s regional Abandoned Mine Land Program, said that the state consults with mine lands developers on permitting, but ultimately, the landowners have the final say on how projects treat the land, with the agency focused more on safety fixes to shore up any problems with the stability of the land itself.

More community-engaged projects could be possible soon, she says. With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act last year, coalfields states suddenly have more funding to restore abandoned mines than ever before. Virginia will get upward of $22.7 million per year for 15 years. Kesterson hopes the windfall will be an opportunity to look at mine land restoration more holistically. “It’ll give us more opportunities to look at the effects of abandoned mine lands on these communities and maybe do community projects rather than a little fix-it here and there,” she said.

This article originally appeared in Grist at https://grist.org/science/the-surprising-biodiversity-of-abandoned-coal-mines/. Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org.

This News App Increases Exposure and Revenue for Black Publishers and Podcasters

Hayti is the first Black-owned mobile app to feature over 2,000 Black podcasters on Android and iOS. (Image: Tim Mossholder/Unsplash)

Like millions of people around the world, tech entrepreneur Cary Wheelous suddenly found himself with a lot of free time during the COVID-19 pandemic. That's when he heard the news that the owner of The Carolina Times — the only Black-operated and owned newspaper in Durham, North Carolina — had passed away and the paper was shutting down.

“I thought, ‘Here we go, another Black newspaper is going out of business,’” Wheelous told TriplePundit. “And I thought, ‘Why does this keep happening to the legacy Black papers that have served our communities for many, many years? What’s going on with them?’”

Wheelous examined news aggregation apps like Apple News, Google News and Flipboard to see what content from Black publishers he could find. He didn’t find much, despite the fact that Black audiences are the largest consumers of mass media in the United States.

“I couldn’t count more than 30, and therein lies the problem that I found,” Wheelous said. “Black legacy publishers are not getting distribution across major mainstream apps that we use every day. I said to myself, ‘I can do something about this.’”

In 2020, Wheelous started developing Hayti (pronounced HAY’-tie) a mobile app that aggregates content specifically from Black publishers. He named the app after a historic African American community in Durham of the same name where The Carolina Times was founded in the 1920s.

“Hayti was a very prominent Black Wall Street. In fact, it was probably just as big, if not bigger, than Tulsa,” Wheelous said, referring to the city’s Greenwood District, one of the most prominent concentrations of Black-owned businesses in the U.S. during the early 20th century that was destroyed in the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921.

With a majority of Black audiences already using social media apps to keep up with the news cycle, a news aggregation app from credible Black publishers enables them to connect with culturally relevant, fact-checked information and push back on the spread of misinformation, Wheelous said.

“The app is a news aggregation app, just like any other app that you use on your mobile phone today. The only distinction is we aggregate traffic, or aggregate content, specifically from Black content creators,” Wheelous said. “We have the same features. You can save articles. You can share articles. We have everything broken out by news, business, sports, politics. You name it, it’s in the app.”

In just over three years, Hayti became the largest mobile app to feature more than 200 Black publishers on Android and iOS, and the first Black-owned mobile app to feature more than 2,000 Black podcasters on both operating systems, too.

“We’ve been able to successfully increase traffic and also increase revenue for not only publishers, but also podcasters who were never able to get the listeners on other platforms,” Wheelous said. “Now they’re getting some of those listeners. The ultimate goal is to drive traffic, but ultimately to boost revenue for these Black content creators to keep them in business.”

The decision to expand the app’s reach into podcasts was in direct response to the needs of its target demographic. Sixty-two percent of Black podcast listeners said they listen to podcasts “at least in part for exposure to hosts that look and sound like they do,” according to a report from the podcast agency JAR Audio. Because of the app’s success in attracting Black podcasters, Hayti is now the official app of the Black Podcasters Association, Wheelous said.

The app promotes podcasters by recognizing a podcast of the week. “But in addition to that, that story actually gets pushed out to our mobile users," Wheelous said. "We’re working hand-in-hand with the Association to conduct webinars and handle promotion to make sure that we can get their stories out via both organizations.”

The Hayti app generates revenue from advertising that enables it to be available for free to users and publishers. The long-term vision for Hayti is to bring in retailers, too, Wheelous said.

“You will be able to come to the app to not only get news or access to podcasts, but you will also be able to support and purchase products from retailers,” Wheelous said. “We want to be a digital Black Wall Street mobile app that will enable users to support our community via the smartphones that they use on a daily basis.”

How Businesses Can Protect Human Rights as They Transition to Clean Energy

A First Solar installation in Las Vegas. First Solar is among the clean energy companies to encounter human rights abuses along their supply chains through human rights due diligence. (Image: U.S. Department of the Interior/Flickr)

Forward-thinking companies are implementing supply chain sustainability initiatives that include environmental and social pledges. But many are also grappling with how to comply with new and evolving regulations as they work to mitigate the risks they face, including those tied to human rights.

For example, multiple countries are collaborating to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to meet the goals set by the Paris Climate Accord and the European Green Deal. They’re also working at the national level to institute laws, such as Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Act (LkSG), that mitigate broad-based environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks and corporate compliance mandates.

As businesses continue to navigate the complex regulatory landscape, they will need the right programs and technology solutions to address one mandate without neglecting another. By taking a risk-informed approach to sustainable procurement — particularly when it comes to low-carbon technologies — leaders can help protect the planet and ethically treat people that produce the products and services that companies procure.

As global temperatures rise, the race to net-zero heats up

Global companies that have tens of thousands of suppliers and third parties operating as part of their extended enterprise are exposed to escalated ESG and human rights risks. They often adopt third-party risk management solutions that can facilitate risk assessments, due diligence checks, supplier audits, and continuous monitoring.

Digitally-enabled companies that can identify, assess, and continuously monitor their risk exposures across their extended enterprise are far better prepared to mitigate them.

Yet, despite their best efforts and intentions, many companies still encounter third-party and supplier risks, including those in the renewable energy market.

Take, for example, the recent experience of U.S.-based solar panel manufacturer First Solar. While auditing suppliers, four sub-contractors in Malaysia were found to have violated worker rights and First Solar’s standards by charging workers recruitment fees in their home countries and withholding their passports and pay, effectively detaining them in Malaysia. First Solar discovered these violations through due diligence, took action to resolve the issue, and voluntarily disclosed the findings in its annual sustainability report in August of this year.

The system worked as designed. Ultimately, rather than sever ties with the sub-contractors, First Solar worked with them to remediate their labor practice issues — enabling First Solar to drive positive social change, support the local workforce, and retain a critical part of its supply base.

Other companies aren’t so lucky.

Since June 2022, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has seized $1.81 billion in goods at U.S. ports, including solar panels and materials used to make them, for violating the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).

Hundreds of U.S. companies were unable to show sufficient due diligence to rebut the UFLPA’s presumption that what they’re importing was created through forced labor. Although nearly 40 percent of seized shipments have since been released, the lapse in third-party due diligence created operational delays, affected revenues, and increased pricing for solar panel modules by 30 to 40 percent.

Why this can be so difficult for companies

Demand for clean energy technologies continues to outstrip U.S. domestic production capacity, compelling many procurement teams to source from suppliers in countries with poor human rights records and opaque supply chains. But, as the UFLPA holds, plausible deniability will no longer pass muster.

China’s infamous human rights record, including the Uyghur genocide, casts a long shadow over the global solar panel supply chain. Companies that have left China to either build domestic production capacity or source from other countries (e.g., Malaysia and Vietnam) remain at risk, because China controls at least 80 percent of global manufacturing at each stage of the solar panel supply chain. This means that solar panels shipped to the U.S. and categorized as manufactured in Malaysia are still predominantly built in China. Malaysia is the country of origin most often cited in CBP statistics for violations of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act.

Therefore, until the domestic production of solar panels, wind turbines and rechargeable batteries begins to approach domestic demand, companies building or acquiring renewable-energy technologies will remain exposed to the risks of modern slavery and other worker abuses in their supply chains.

How to advance on climate without retreating on human rights

Broad ESG regulatory compliance is not an implementation project, it’s a journey. As business leaders turn to technology to improve supplier visibility and third-party risk management, there are five considerations they should keep top of mind.

Clearly define what you're doing. Establish a well-defined charter that sets the purpose, business objectives and scope around current risk profiles, how third parties are used and managed, and which ESG regulations, standards, and frameworks must be adhered to.

Chart a roadmap. Create a roadmap of your company’s ESG programming to provide a clear starting point and outline the implementation phases for your risk priorities, with continuous checkpoints and insights.

Get buy-in, internally and externally. Secure cross-organizational alignment within your company, and then clearly communicate ESG expectations with your third parties to ensure governance and compliance requirements are understood and met.

Identify the changes you plan to make — and how you'll make them. Create blueprints of functionality, technologies, and integrations needed for each risk domain to help inform and give definition to the business processes needed to make it happen.

Set your priorities, and start investing in them. When considering technology investments, business leaders should think big, start small, and grow fast. Companies need modern business solutions for modern business problems.

- Think big: Take a comprehensive view of your ESG strategy first and select a system or software platform that can support the majority of them with consistency.

- Start small: Implement one or two of the most critical programs you've identified, because ESG risks and regulations will change, along with compliance requirements.

- Grow fast: Expand quickly through a series of implementations that incrementally expand risk domains as needed.

With the right programs and tools, companies can conduct more thorough due diligence that vets and assesses suppliers and third parties for inherent risks. These business solutions can ultimately help companies reach their climate and emissions goals and requirements while preserving the human rights and dignity of the people who ultimately fuel their supply chains.

Public Transportation Has a Lot of Problems. Can Microtransit Help to Solve Them?

Public transit ridership plummeted around the world at the start of the coronavirus pandemic and never fully recovered. Some riders may be hesitant to revisit densely packed public spaces, but convenient access to public transit remains a key reason why ridership continues to lag.

As housing prices skyrocketed in major cities and the pandemic eased the transition to remote work, people across the U.S. and around the world started moving out of downtown areas in search of lower costs. That means where people live in relation to historic transit hubs is quickly changing, further complicating the fact that only around half of urban residents worldwide have access to public transit near their homes.

Camden, New Jersey, where an estimated 70 percent of residents rely primarily on walking or public transit, is among the latest cities looking toward technology to solve their transportation problems. With the newly launched Camden Loop, the city joins hundreds of localities around the world in supplementing fixed-route public transportation with on-demand microtransit.

For commuters, microtransit systems are similar to ride-hailing services like Uber or Lyft: The user pulls up an app on their phone to order a ride, they're given an estimated time of arrival, and they meet the driver at a nearby corner for a shared ride with others traveling in the same direction. But behind the scenes, these systems are co-created by municipal governments and local stakeholders to fill in public transit gaps and get residents where they need to go.

As of last year, about 450 companies were offering microtransit services worldwide, Lukas Foljanty, a German transportation analyst focused on microtransit, told Bloomberg.

Microtransit meets crucial needs in Camden

Situated across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, the city of Camden is home to around 71,000 people. With nearly 34 percent of the city's population living below the poverty line at the time of the last Census, the former manufacturing hub is now the poorest city in the Garden State.

Those rates of poverty bring with them familiar challenges — including lack of access to essential services like healthcare facilities, schools and grocery stores selling fresh food.

"About a third of the households in the city do not have dependable access to a car," said Dana Redd, who served as mayor of Camden from 2010 to 2018 and is now CEO of the nonprofit Camden Community Partnership. "I certainly can attest to that. Having been born and raised in the city of Camden, raised by my grandparents, we did not have a vehicle in our household. And I relied on public transportation to connect to employment and also to connect to school."

The Camden Loop launched in July as a joint effort between the city of Camden, Camden Community Partnership and the microtransit developer Via. People took notice early on. "In the first week, residents were texting me how wonderful this option is and how wonderful the service has been," Redd told us.

The Camden Loop has provided almost 15,000 rides so far. Nearly 7,700 unique riders — equivalent to over 10 percent of the city's population — have established app accounts to utilize the Camden Loop.

The on-demand service helps riders fill in gaps between fixed bus routes and crucial hubs both inside and outside of the city, including New Jersey Transit hubs in Camden's downtown and about seven miles away in the affluent suburb of Cherry Hill.

"Fixed-route does a great job of connecting people, but unfortunately, just due to the way that fixed-route works, it can't reach everywhere within a community," said Eric Gardiner, head of East Coast partnerships at Via. "That's where having a technology-enabled public transit service — where you can indicate from a demand side, not a supply side that you need a ride — allows you to cover a much greater area and fill in the gaps, while also connecting that first-last mile to intermodal hubs."

Addressing access 'deserts' in underserved communities

Early data from the Camden Loop indicates riders are using the service to get to school, work, and essential services in ways that are faster, easier and cheaper than what they were able to do before. "The trips that people are taking are ones they previously could not take on public transit," Gardiner said. "They're moving around the community in a completely different way."

That includes easier access to transportation and shopping that is available in Cherry Hill. While only a few miles from downtown Camden, the suburb's offerings are a world apart, with public transportation connecting to North Jersey and New York, as well as ample access to shopping centers and grocery stores that are few and far between within the city proper.

In particular, about 30 percent of people who visit the ShopRite in Cherry Hill are from Camden, Redd said, a journey that for many is an arduous combination of walking and buses that stop only a few times an hour. Even more so in cold and icy weather. "I can remember as a young person growing up in the city, being raised by a grandmother, just the struggle of getting to the market, and then after you shop, the struggle of getting home," she said. "Trying to do that via public transportation was not something I looked forward to as a little girl."

The city's major hospital and Camden's public high school — which Redd describes as "the center of activity" on Camden's South Side — are also among the top stops in the first four months of service on the Camden Loop.

Ensuring accessibility for those who need it most

As far as transit goes, the Camden Loop is cheap and easy. Rides cost $2 each, compared to $2.25 for standard fare on New Jersey Transit buses. "It's very affordable here for residents, but we also have other ways to offer reduced rates — including the weekly pass, which is a $7 a week charge for up to four rides per day, or a monthly pass, which is $26 per month for up to four rides per day," Redd said.

Beyond cost, the service is also accessible. Those who are tech-savvy and don't mind walking a block to a designated pickup point can utilize the service the same way they'd use the carpool function on Lyft or Uber, with average arrival times of around 15 minutes. People who don't have a smartphone or don't like technology can call to get a ride, while those with mobility challenges can request door-to-door service rather than corner-to-corner. The shared vans can also accommodate wheelchairs

"We were able to hear from [people in the community] well in advance of us designing this, finding out what the concerns were, finding out what the needs were, and really looking to address some of those deserts — locations where the first-mile, last-mile barriers were very intense," said Brian Bauerle, vice president of Camden Community Partnership. "What was most important to us was finding a partner like Via, who had the expertise to hear our voice, what we wanted to represent for the community, and help us implement that."

A global proving ground for microtransit

Hundreds of microtransit programs like the Camden Loop are operational across the U.S. and around the world. Via alone has more than 50 municipal partners in the U.S., where the company provides the technology and works with community partners to build unique microtransit programs that meet city needs.

Those partners include Camden's neighbor to the north, Jersey City, which sits across the Hudson River from Manhattan and has seen promising results since launching the Via Jersey City microtransit service at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. "Low- to moderate-income residents have access to 35 percent more jobs, schools and hospitals within 30 minutes," Gardiner said.

It's not just Jersey that's seeing success with microtransit. Birmingham, Alabama, increased access to schools and jobs by 80 percent by using the microtransit model in partnership with Via, while the traditionally car-heavy Dallas-Fort Worth suburbs are now home to the most popular microtransit program in the U.S. — serving around 70,000 riders monthly.

Of course, microtransit isn't a panacea to our public transit problems. "At a very basic level, everywhere that exists is not a candidate for microtransit," Gardiner said. "If you look at high-capacity corridors where you get a bunch of people that are riding a fixed-route bus quite regularly, there's no better way to move those people than on a fixed-route bus."

Beyond that, news reports have documented inefficiencies in some city programs, or cases where ridership is lower than expected for various reasons.

But for Camden, the Loop service is proving an effective way to get people around without multibillion-dollar infusions into the local public transportation system. The fleet now includes six vehicles, most of them driven by Camden residents. Average utilization is around three riders per vehicle hour, which is pretty solid considering the city's relatively low population and frequent rides outside the city that can easily take 20 minutes or more.

"In the places where it makes sense, this is very much a type of public transit that fits in for a couple of core goals of community," Gardiner said. "One is in places that are just under-penetrated by fixed-route, where there's no transit available. The other is as a first-last mile service. A big part of making sure that it's used correctly for the overall transit network is the service design and the goals upfront, and the Camden Community Partnership did so much work ahead of time prior to launching this."

The early results are enough to make city organizers feel confident in their decision, with plans to add weekend hours, additional zones near Camden, and more vehicles as needed thanks to funding from the state of New Jersey for 2024. "This has nowhere else to go but up and certainly to improve the lives of residents in Camden," Redd said.

Images courtesy of Via

DEI Lives to Fight Another Day

People hold signs at a demonstration in 2020. This form of public protest has largely given way to a wave of quiet employee activism in support of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies across U.S. workplaces. (Image: Amy Elting/Unsplash)

Advocates for corporate diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies are finding support from a new wave of employee activism, in which workers deploy quiet strategies to press for progress from the bottom up. Business leaders who value a diverse workforce can learn from these creative organizers and improve their ability to attract and retain top talent from all walks of life.

The importance of institutionalizing diversity and inclusion

Diversity hiring has acquired a strong track record for delivering financial results. The well-known human resources expert Josh Bersin recently summarized the state of affairs in a 2021 white paper titled, “Elevating Equity: The Real Story of Diversity and Inclusion.”

“In fact, we won’t even debate the fact: More than 200 studies show how diversity in business leads to greater levels of innovation, customer service, employee engagement, and long-term growth,” Bersin wrote.

However, achieving and maintaining a diverse workforce is a complex task. There are no shortcuts. Bersin, for example, underscored the importance of following up diversity hiring with ongoing programs that support inclusion and employee satisfaction.

The case for managerial responsibility

Despite the informed views of Bersin and other experts, though, DEI shortcuts have become commonplace. Businesses routinely call upon vendors to conduct one-off employee training sessions, rather than making DEI programs a permanent fixture within the organization.

Although they're popular, DEI shortcuts are known to be ineffective. For example, a widely cited 2006 study found that sporadic DEI training sessions mostly fail to change behavior or improve diversity hiring. The authors advocated for ongoing policies that are institutionalized within the company.

In particular, the team of 21 academic researchers from Harvard, MIT and other institutions emphasized that managers must be made responsible for diversity hiring. Members of the same team made a similar case in a 2018 article, in which they advocated for DEI programs that focus on managerial engagement rather than legalistic mandates.

“The antidiscrimination measures that work best are those that engage decision-makers in solving the problem themselves,” they wrote.

DEI is on the ropes, but employees still care

As Bersin noted in 2021, many businesses did hire dedicated DEI staff and increase their commitment to DEI programs after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. However, much has changed since then. One big change this year is a wave of layoffs targeting corporate DEI staff, especially within the tech sector.

Sustained, multi-level attacks on corporate ESG (environmental, social and governance) principles have also muted the willingness of companies to discuss ESG goals and related social issues.

In addition, the dramatic, attention-getting street protests that characterized employee activism during the Donald Trump administration have largely faded from the media spotlight. That has eased the pressure on corporate leaders to respond to social issues.

However, pullback on DEI policies at the top of the corporate ladder does not necessarily reflect employee sentiment. Studies show that employees continue to value DEI programs at work.

A Pew survey last spring, for example, found that 56 percent of employed adults say that DEI programs at work are mainly “a good thing. Pro-DEI sentiment is stronger among women, at 61 percent, as well as younger workers ages 18 to 29 (68 percent), and those identifying themselves as Democratic (78 percent), Black (78 percent), Asian (72 percent), or Hispanic (65 percent), the study found.

These numbers provide support for companies to continue deploying DEI policies that attract employees beyond the traditional hiring pool, and to reach out to an increasingly diverse and socially aware workforce.

DEI from the grassroots up

The Pew findings also indicate that business leaders who drop the ball on DEI may encounter pushback from their own employees. Researchers who study employee activism have in fact noticed that employees are institutionalizing DEI goals among themselves.

Greater Good Magazine, a publication of the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California – Berkeley, outlined this employee-centered trend in an October 30 article titled, “How to Keep Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Initiatives Alive at Work."

The authors, Columbia University professor Peter T. Coleman and University of San Francisco assistant professor Allegra Chen-Carrel, both work as DEI consultants for large employers.

In the article, they describe an emerging trend in which employees are driving the DEI conversation. “Internal activism is on the rise, with four in 10 of all employees and half of millennials reporting that they had spoken out about controversial issues at work,” they reported.

They observed employees taking lowkey pathways to foster change, such as building support networks among themselves, while managers are choosing to practice diversity hiring in the absence of strong corporate leadership.

Keeping up with the fast pace of lowkey employee activism

In their article for Greater Good, Coleman and Chen-Carrel provide employees with a toolkit for lowkey activism while urging employers to become more alert to employee issues and concerns.

Creating an opportunity for mediation is one key piece of guidance. “This can involve something as simple as offering opportunities for coworkers and managers to share their concerns by simply taking time to listen, ask questions, and acknowledge problems,” Coleman and Chen-Carrel advise.

They also take note of employee-driven, self-care strategies that could be incorporated into a company’s wellness programs, such as relaxation exercises and time for self-education on broader social issues.

For employers, affirmative action plans, diversity committees, employee surveys and other data collection methods, and annual reporting are listed among the action steps.

Further, DEI leadership requires companies to identify and change harmful corporate practices, provide more support for effective practices, adapt to change, and respond proactively to tense situations, Coleman and Chen-Carrel argue.

“When destabilizing events occur, such as scandals, mergers, leadership changes, or even wider social movements such as Black Lives Matter or #MeToo, there can be energy and momentum for organizational change,” they write.

All of this involves an investment of corporate resources. Nevertheless, the long-term payoff can be significant in terms of avoiding costly lawsuits as well as attracting top talent and building a positive brand profile.

Filling the gaps

To be clear, progress on diversity within corporate walls can only go so far. In his 2021 white paper, Bersin took note of a sharp backslide on civic governance in the U.S. since the 1970s. He cited a weakening of equal access to housing, voting rights and business opportunities among the evidence. Equal access to education and health care can also be added to the list, in light of recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court.

To the extent that these attacks on human and civil rights impact employees, the pressure for change in the workplace will continue to rise. Companies with active, institutionalized DEI policies are in a good position to turn that tension in a positive direction. As for companies that have pulled back on DEI, they may need to rethink their position before the tension boils over.

Homepage image: Tim Mossholder/Unsplash

The Push to Upgrade the World's Washing Machines and Keep Microplastics Out of the Ocean

PlanetCare's filter attaches directly to a washing machine's drain hose to capture the microfibers released from clothes when doing laundry. (Image courtesy of PlanetCare)

The term microplastics often conjures images of plastic bags and bottles breaking down in the ocean. But it isn’t just decaying litter that creates the minuscule pieces now found in every part of the planet — including human bloodstreams. The bulk of products that make up modern life add to the microplastic problem.

Microplastics make a huge problem

“Just by doing our laundry, the amount of microfibers we throw into the oceans is the same as if you would take a plastic bag and throw it into the sea,” said Marjana Lavrič Šulman, chief brand officer at PlanetCare, a company that makes washing machine filters to capture these fibers. She’s not talking about one bag per year. For the average household, doing laundry is the same as tossing a plastic bag in the ocean every week.

“You would never do that,” she said. Not on purpose, anyway. But the difference is what we can see and what we can’t. “[When] doing your laundry, you don't see it, but the amount of plastic is the same. So, every single user that we managed to onboard basically does not throw 52 plastic bags per year into the ocean.”

The equivalency is startling, to say the least. But it hasn’t been enough to get the industry to act. “Originally PlanetCare started with an integrated filter for washing machine manufacturers,” Šulman said. The company pitched that design to manufacturers in 2017, only for founder and CEO Mojca Zupan to be told that she would be better off adopting a dolphin.

Pivoting to consumers

“The hardest lesson was to realize that there are no quick wins, even though you think you have a great product that solves a very serious problem,” Šulman said. “The industry just doesn't care. And for us to be resilient enough to show that, then you change the business model. Then you go to the end consumers. Then you turn to those who do care.”

PlanetCare’s first aftermarket filter launched in 2019 and has 7,000 users worldwide. It’s an impressive number for a startup that doesn’t have an advertising budget, access to venture capital or corporate partners. Instead, the company relied on an EU grant and funding from a family in its home country of Slovenia. “We’re really actively searching for investors,”Šulman said.

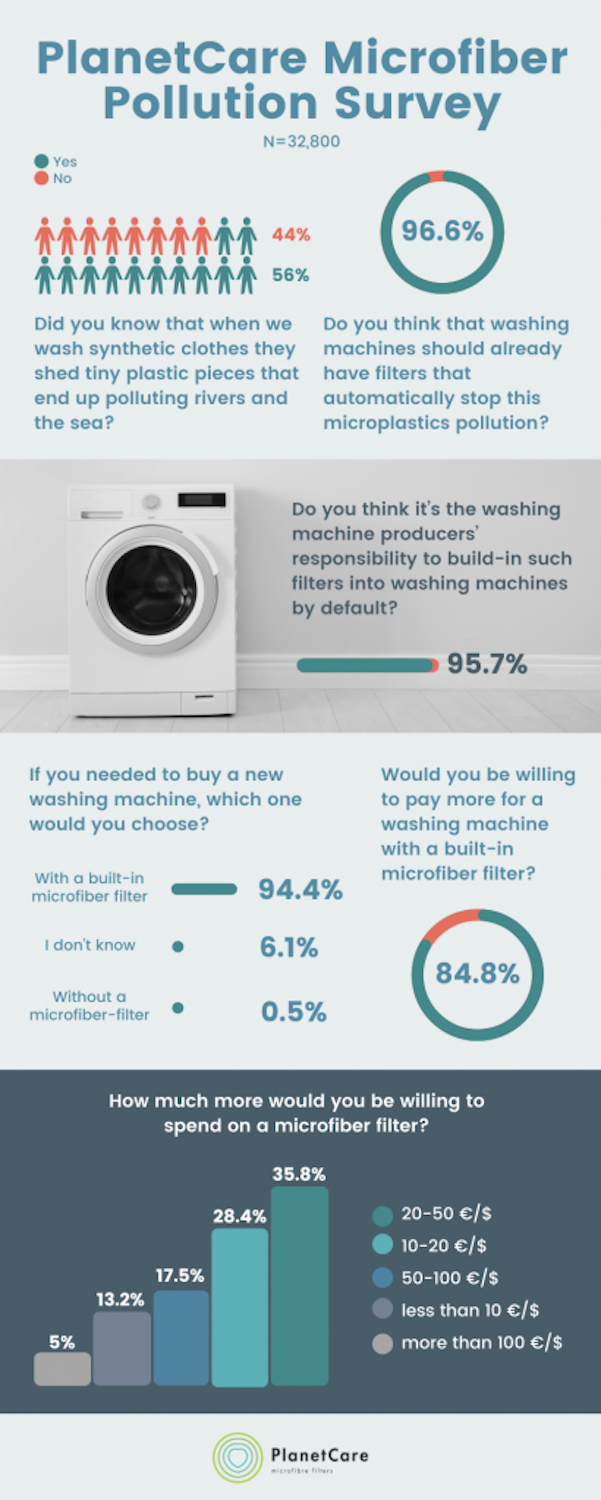

That search includes a successful crowdfunding campaign aimed at its second-generation filter — PlanetCare 2.0. Pledges are far outweighing the company's original goal, which goes to show a significant number of people are interested in doing the right thing when it comes to microplastics. Additionally, a survey conducted by the company in 2021 found that almost 85 percent of respondents would pay more for a new washing machine with a built-in microplastic filter versus a machine without one.

“After four years, we have now made it better,” Šulman said of the upgraded model. “It's hardly the same filter. We say it's an improved version of the first one, but really everything's new. Everything's different.”

The PlanetCare filter attaches directly to the drain hose, doesn’t require any electricity to run and is compatible with all washing machines. Independent testing shows that PlanetCare 2.0 captures 98 percent of fibers, though variation is expected with different machines and cycles and will also depend on what is being washed.

A need worth meeting

While it is disappointing that manufacturers were not interested in the original integrated filter — nor fair for the industry to continue to shift responsibility to the consumer — there is a definite need for aftermarket filters for microplastics. In 2013, 840 million washing machines were in use worldwide, according to the latest available data. More are certainly in use now, and it will be a long time before they all need replacing.

As with the shift to electric vehicles, upgrading before an appliance has worn out just to get one with an integrated filter would do more harm than good. In this respect, PlanetCare has the potential to fill an enormous need as hundreds of millions of machines could use the external filters. The issue is making it happen, especially in poorer and more remote regions.

Another benefit to PlanetCare’s external filters is the closed-loop system. Used filter cartridges are sent back to the company where they are cleaned, refurbished and redistributed. The microfibers are collected for recycling. At this point, the pool is too small to have any products on the market that are made from them, but the company’s pilot program has produced insulation mats and mesh for chairs.

The new model features a much more efficient cartridge than the first, Šulman added, and the cartridge filters fill up in about four weeks with average use.

While there is a carbon cost to shipping the filters back and forth, asking the consumer to wash and reuse their filters at home would send the fibers into the water system anyway — defeating the purpose altogether.

“We know this is a pain of ours, that sending the cartridges back and forth is not really the most environmentally-friendly thing we can do,” Šulman said. “That's why for those really far-away users, we say, ‘Please don't buy the small starter kit with only three spare cartridges. Get the large one and we only have to do it once per year.’”

The company has a clear vision for the future that includes local refurbishing units, so it won’t be necessary to send the cartridges back to Slovenia. “Once we have 5,000 users in Australia there will be a local unit, or once we have 5,000 users on the West Coast, or on the East Coast, or anywhere in Europe,” Šulman said. “It's an easy, very easy system.”

Patagonia has leveraged its brand recognition with appliance maker Samsung to develop an external microplastic filter, too. As a producer of outdoor clothing and gear, Patagonia’s products rely heavily on synthetic fibers that shed microplastics — which is what prompted the company to form the partnership two years ago. Samsung also introduced a "less microfiber" cycle that it says can be downloaded as an update to any of its machines. Still, it begs the question: Why aren’t manufacturers more motivated to include integrated filters on all new machines?

“I was naive five years ago, and I actually thought there would be somebody who would just do it because it's the right thing to do. Because we all live on the same planet, and we all use the same resources, and we all drink the same water,” Šulman said of the industry’s lack of interest in building models with filters already installed to remove microplastics. “But I still hope the filter gets integrated without the regulative pressure.”

Images courtesy of PlanetCare

We Can’t Rely on Technology to Solve Plastic Waste

Sachets containing single-use servings of liquid or gel products, like soap and shampoo, for sale in Indonesia. (Image: Ikhlasul Amal/Flickr)

In 2016, a groundbreaking report from the World Economic Forum revealed the world’s oceans could have more plastic, by weight, than fish by 2050 if nothing changes. It was part of a growing chorus raising alarms about the flow of plastic from consumer products into waterways and oceans around the world. Specifically, consumer goods brands were seen as key actors in creating solutions to save our oceans.

At the Our Ocean Conference in Indonesia in 2018, one of the world’s largest users of plastic packaging shared details about its ambitious and innovative effort to address one of the biggest plastic waste challenges in the developing world: the sachets used to package small quantities of household products like detergents and soap. To much fanfare, Unilever announced it would begin operating a factory in Indonesia using a new chemical technology called CreaSolv to recycle sachets — giving hope the plastic pouches could, in the future, become part of a circular system.

“Billions of sachets are used once and just thrown away, all over the world, ending up in landfill or in our waterways and oceans,” said David Blanchard, Unilever’s chief research and development officer, in a statement announcing the plan. At the time, he said Unilever aimed “to scale the technology with industry partners, so others — including our competitors — can use it.”

The company also announced an investment into crowdsourced solutions for sachets and a plan to make all the plastic packaging it produced either compostable, recyclable or reusable by 2025. It seemed the company was serious about ending its dependence on single-use plastic.

But Unilever quietly scrapped the chemical recycling pilot earlier this year, citing insurmountable logistical, financial and technical challenges. TriplePundit reached out to learn about what happened and received this response from a spokesperson via email: “We’re working on a range of solutions to reduce our use of multi-material sachets … This is a complex technical challenge, with no quick fixes, and we are fully committed to working with industry partners and other stakeholders to develop viable, scalable alternatives that reduce plastic waste.”

For those looking to solve the plastic crisis, the lack of context about why the CreaSolv effort didn’t work was disappointing.

“Unilever's management has acknowledged the detrimental effects of plastic sachets in Asia,” said Devayani Khare, Asia communication officer at the nonprofit Break Free from Plastic. “Yet the corporation's actions have fallen far short of the mark when it comes to actually tackling the issue. We still don't have viable solutions to plastic sachets.”

The problem with sachets

Sachets are small, soft plastic pouches that can hold small amounts of liquid or gel products. For Unilever, sachets are a way to sell cosmetic products — including soap, shampoo and conditioner — in single-use servings in the developing world. If you spend time in Southeast Asia, Latin America or Africa, you’ll quickly grow familiar with the sight of sachets for sale at roadside stalls seemingly everywhere.

Like most flexible packaging, sachets are made of multiple materials that are highly challenging to separate, and no mainstream solution exists to recycle them. Because they are typically sold in developing countries, and in rural areas, there often isn’t even an effective waste management system to collect them. The result is sachets ending up as litter, where they can easily flow into waterways and our oceans. Among the many problematic pieces of packaging out there, sachets are among the most challenging and pressing.

While plastic sachets are a big issue in the developing world, they’re a problem in the United States, too. The most common place that consumers encounter them is in fast food, where ketchup, mustard and other condiments are packaged for single use. Like their counterparts in Indonesia, they can’t be recycled using traditional methods, such as the systems that exist for plastic beverage bottles.

There are two ways to approach the sachet challenge. One would be to eliminate their use. But because of the popularity of sachets in remote regions, and the lack of alternative ways for major brands to sell their goods to those consumers, most big brands have focused on finding a way to make these mixed, multi-layered plastics recyclable. Some, like Unilever, looked toward a nascent technology: chemical recycling.

Traditional mechanical recycling methods generally clean, melt down, and then reconstitute a single type of plastic, like polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which is commonly used for beverage bottles. Chemical recycling, on the other hand, breaks down complex plastics and multi-material packaging into constituent parts.

“These technologies can be broadly lumped into three big categories: purification, depolymerization and conversion technologies,” said Anja Brandon, a material scientist now with the nonprofit Ocean Conservancy.

Purification turns hard-to-recycle plastics into usable polymers for other applications. Depolymerization converts plastics into non-plastic chemicals for a variety of uses. And conversion turns plastic into fuel to be used in chemical or industrial applications. One thing they all have in common, though, is their complexity.

“Chemical recycling technologies have much, much larger climate footprints than mechanical recycling,” Brandon added.

This creates two challenges: cost and scalability. The CreaSolv project used a type of purification technology. But to address the amount of sachets in just Indonesia, the effort would have to be expanded to several plants across the country. This cost could make scaling the technology a challenge and, based on the background TriplePundit received from sources like Brandon, may have played a role in the project’s demise.

Technology alone isn’t a solution

To many, the news about the failure of the CreaSolv pilot shows the limitation of recycling technology as a solution for hard-to-recycle plastics and multi-material packaging like sachets.

“There is an urgency for Unilever and other food and consumer companies to quit sachets,” Khare said. “Silence is insincerity when corporations advertise certain values but are not as sincere in their actions.”

A completely different paradigm is needed to really solve the problem when consumer companies sell products in developing markets. Instead of producing and selling millions of sachets in regions without effective waste management systems, Unilever and others are challenged to ensure the waste created from their sales can be handled properly, and not end up in the environment.

One way to ensure this? Extended producer responsibility, or EPR. In most markets today, companies can sell sachets, bottles, and other single-use plastic and then ignore when that plastic ends up in the environment, harming marine life or polluting waterways. EPR mandates that companies take responsibility for plastic packaging even after it's sold to consumers. The PET bottle fees we pay at grocery stores in many U.S. states, which are factored into the price we pay, are an example of an EPR system in action. The goal is to create a system that supports the recycling and recovery of bottles before they end up in landfills.

Historically, many consumer brands have opposed strict EPR, whether in Indonesia or in the U.S., instead promoting technology as a solution. That has changed in recent years, as industry groups like the Consumer Goods Forum are, partly due to consumer pressure, open to adopting some form of EPR. This is a sign that, perhaps, the tide is really starting to shift.

“Unless Unilever switches their packaging system, they will not solve the plastic waste problem in Indonesia,” says Ibar Furqonul Akbar, who leads the plastic work at Greenpeace Indonesia. “Many consumer brands, they just want to rely on recycling itself, but they don't consider reduce or … reuse in the first place.“

One lesson to learn from the Indonesia pilot is that technology is not always the solution and simple models around things like reuse can work better, especially in emerging economies.

“Perhaps eliminating these single-use sachets and prioritizing sustainable packaging alternatives would be better for Unilever,” Khare added.

In fact, reuse is promoted by local brands across Indonesia, with zero-waste stores selling locally-made shampoo, soaps and conditioner — the main products sold in those sachets — in reusable containers. Now in several cities, these stores are expanding even into the countryside. Similarly, refill and reuse systems are being set up to reduce single-use plastics in Africa and Latin America, but thus far these local efforts haven’t received adequate backing from global brands

The main reason that companies are hesitant to embrace reuse and refill systems? The cost. Plastic is cheap and easy to ship to remote regions. The unfortunate reality is that going to a refill shop can often cost more than buying single-use sachets from a street vendor in places like Indonesia. The cost of circularity is borne by the consumer, not the polluters.

Meanwhile, many brands are still pushing recycling technology as a stand-alone solution. Last year, PepsiCo invested $35 million in a closed-loop local recycling fund. Colgate, Coca-Cola, Keurig and others are also putting millions of dollars into so-called next-generation recycling technologies. Whether they succeed or end up as costly delays, like the CreaSolv sachet recycling project, remains to be seen. But can we afford to wait?