Protecting Privacy While Monitoring Employee Health in the Age of COVID-19

Companies planning how to reopen safely for business in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis are considering digital tools to track their employees’ health status. But without adequately protecting data privacy, such moves could backfire. The specter of a surveillance economy and “Big Brother” loom large in certifying who is a “safe” worker.

One suggestion of how to do this sensibly comes from MIT Professor Alex “Sandy” Pentland, a prominent data scientist who co-leads the World Economic Forum’s Big Data and Personal Data initiatives. In a recently published white paper, Pentland argues that digital identity could certify users’ health status while safeguarding their sensitive health data. He proposes that hospitals, credit unions, banks, and other civic institutions serve as repositories for people’s health data, much as they already do for their financial and other personal information. This would form the basis of citizens’ “digital identity,” and would determine their ability to work and perform other activities.

Keeping personal data in local institutions that already have a “need to know” or are under direct citizen control would tackle privacy concerns and avoid the creation of national or state-wide registries, as these are tempting targets for misuse, according to Pentland. Health certification could be easily integrated into the digital identity infrastructure that is already used for authenticating payments and help decide what sort of businesses are safe to reopen, and make contact tracing more efficient, without jeopardizing personal privacy.

“With this kind of digital identity, people can certify their health status to merchants and employers in the same way their credit card or identity is verified,” Pentland said in a press release. “They can also see which places are safe to go—for instance, places that are uncrowded or recently cleaned, and where customer-facing employees are infection-free, all without compromising their personal privacy.”

Photo: Under a proposed digital health ID, employees in public-facing positions could be certified as safe, inspiring consumer confidence. (Image credit: Irina/Unsplash)

Privacy advocates on alert

For privacy advocates who have viewed with concern how other countries have been implementing technology to track citizen health in the wake of COVID-19, this may sound too good to be true. China, for instance, has alarmed human rights advocates with the rollout of its software surveillance for the COVID-19 pandemic. There is little transparency about how the Chinese government is using personal data to sort people into various categories of health status, ABC News reported, leading to possible abuses. Other Asian countries like South Korea, China and Taiwan also didn’t bother to seek permission from individuals before tracking their cellphones to identify suspected coronavirus patients.

In Europe and the U.S., with stricter privacy laws and expectations, it’s a different story. While the European Union sees digital mapping to track coronavirus contacts as key to lifting Europe’s lockdown, the EU asserts it is doing so in a way that conceals citizens’ identities and that use of mobile applications will be voluntary for individuals, based on users’ consent.

Meanwhile, some companies are already using technology for health monitoring like Amazon, deploying thermal cameras at warehouses to scan for fevers faster.

Look out for ethical risks

While a voluntary opt-in is one way of finding the right balance in using technology to monitor COVID-19, ethical concerns should stay front and center. “The risk is that in an emergency everybody rushes to find a solution without regard for longer-term societal and ethical risks,” says Elaine Weidman Grunewald, co-founder of the AI Sustainability Center in Stockholm, a global hub that focuses on ethical pitfalls in the use of AI and other technology, as TriplePundit has previously reported. “The most obvious risks are misuse and overuse of data for unintended purposes as well as reusing that data in a way that could result in different forms of discrimination and bias,” she told TriplePundit.

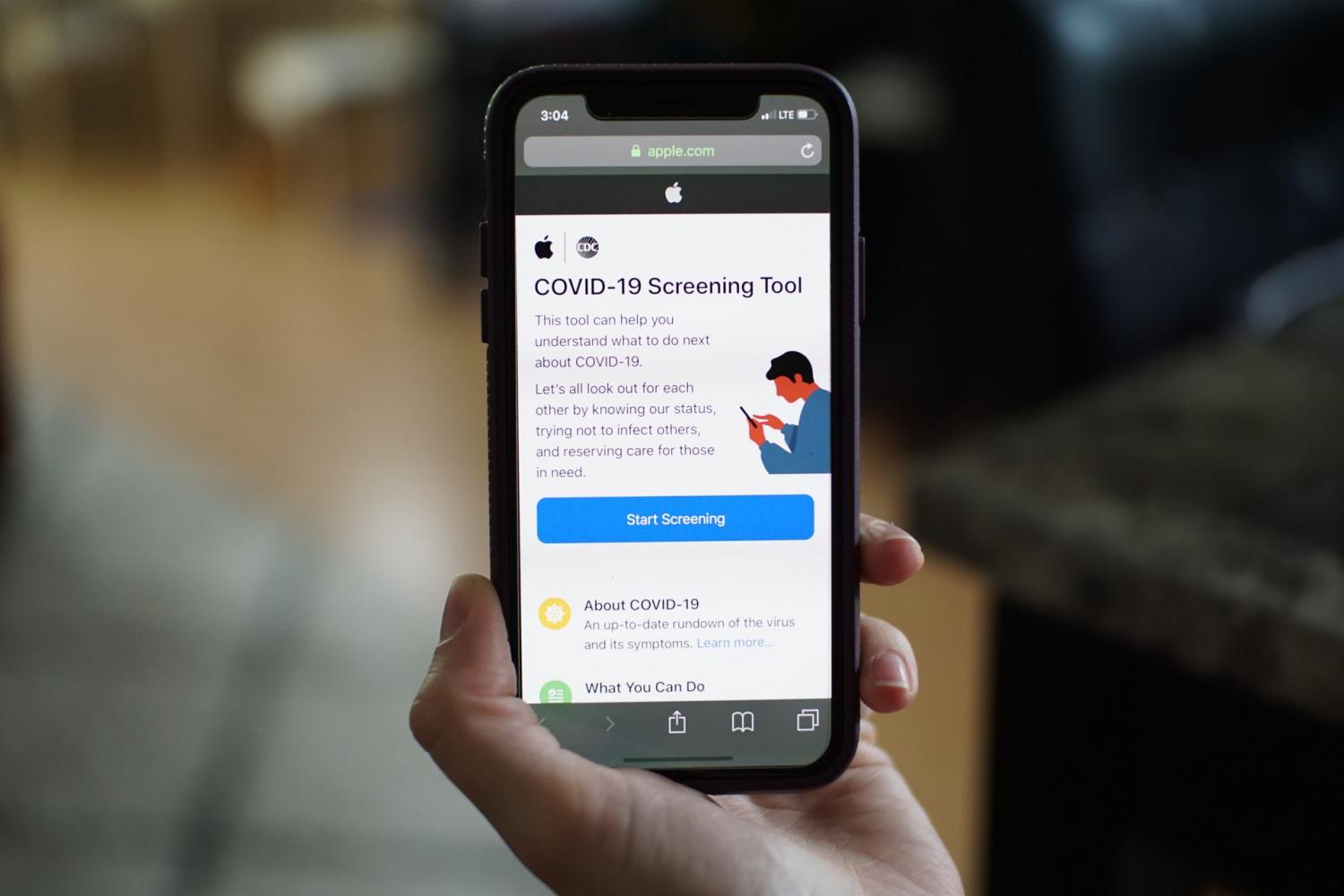

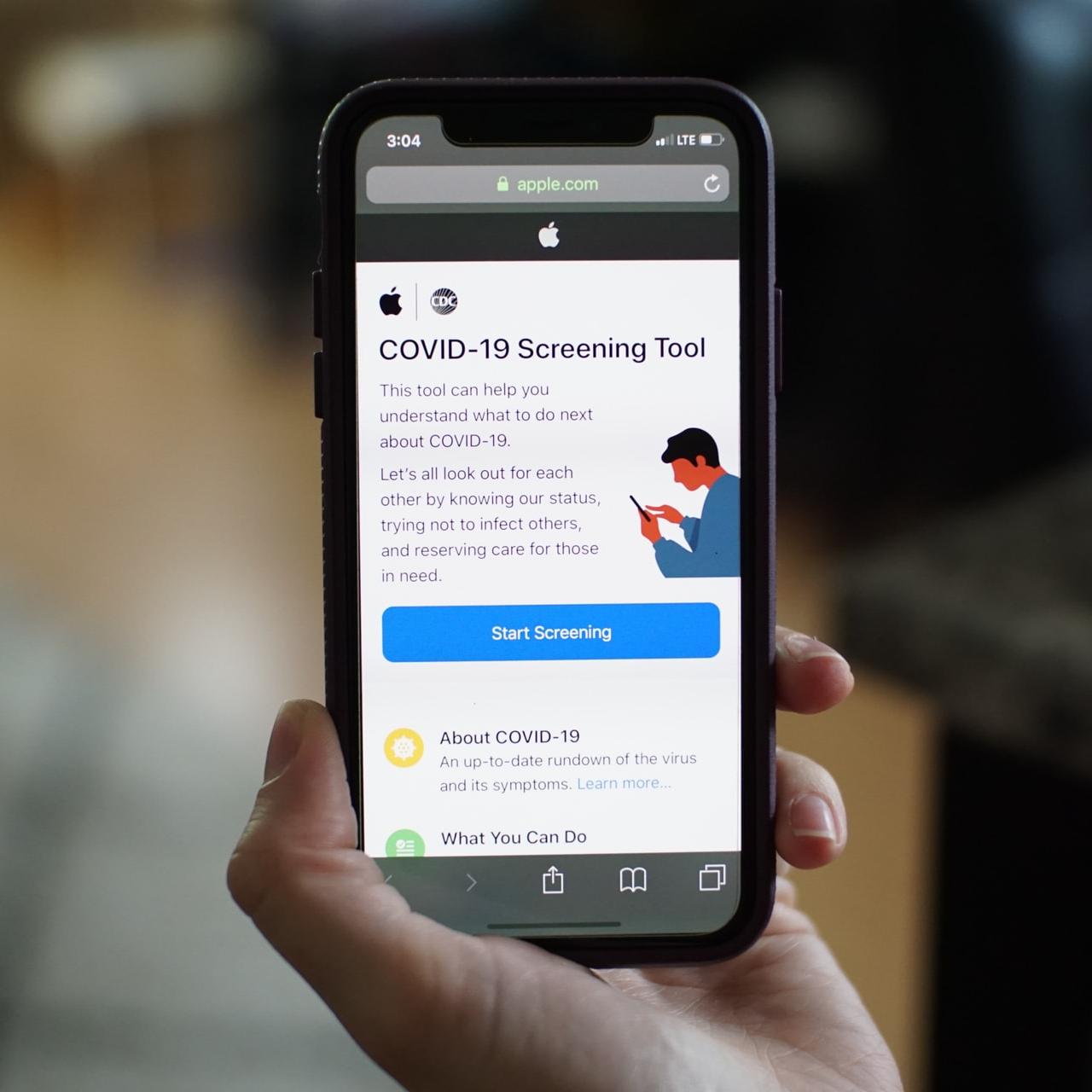

The privacy implications are fully apparent when tech giants jump into the mix, with their access to huge amounts of data and, some have argued, too little transparency and oversight on how they use that data. For example, Apple and Google recently announced plans to launch a voluntary contact tracing tool to help individuals determine whether they have been exposed to someone with COVID-19.

Weidman Grunewald says she recognizes that companies need to have some kind of solution for monitoring health of employees before they bring people back to work. “Technology is an incredibly powerful tool in helping to combat the disease. But I would recommend that companies be transparent about how they will and will not use this data and be open and transparent about that, and let people opt in.”

As Pentland points out in his paper, using blood tests to certify people who are verifiably immune from the illness or vaccinated, and therefore “safe” to rejoin the workforce is not a new concept. This sort of certification exists in the form of tuberculosis test documentation for food workers and proof of vaccinations for childcare workers, for instance. He argues that financial incentives could help kick-start the process. The government, for instance, could offer tax breaks to companies that employ “safe” workers. Businesses, meanwhile, could offer increased pay to motivate these same workers to take public-facing jobs. Additionally, businesses could certify that they hire only safe employees in public-facing positions, which would inspire customer confidence.

A privacy trade-off in the COVID-19 age?

There is well-documented skepticism among the public about protection of their personal data. A majority of Americans are concerned about the way their data is being used by companies (79 percent) or the government (64 percent) and most feel they have little or no control over how these entities use their personal information, according to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center.

But when it comes to getting back to work, people may be willing to make a privacy trade-off. A little more than half of Americans now back anonymized government smartphone tracking, according to a Harris Poll survey of about 2,000 people conducted between March 28 and 30. A new age of digital surveillance could be one of the many ways that coronavirus is changing the world as we know it.

Image credit: Cory Checketts/Unsplash

Achieving Paris Agreement Goals can Pay Off in the Trillions

A study published by Nature this month calculates the potential loss nations would face if they fail to take action toward climate change, as well as the benefits they would reap by maintaining the standard set by the Paris Agreement: keeping global temperature increase to well below 2 degrees Celsius since the industrial revolution.

Every single nation would benefit from climate action and be hurt by inaction, the study shows. The numbers are as follows: If current emissions reduction efforts continue, the world would see a benefit anywhere between $127 trillion and $616 trillion through until 2100.

However, if countries are unable to reach their Nationally Determined Contributions from the Paris Agreement, the global economy could lose between $150 trillion to $792 trillion from now through the end of this century.

Carbon reductions in coronavirus times

Publishing this study outside of the novel coronavirus pandemic would have been a firm push to national governments. And despite the constant photos that remind us of the sudden fall in COVID-related emissions, organizations including the UN have made it clear that the world will still confront many risks linked to climate change. In many ways, however, national leaders are being pressed in the opposite direction.

Shelter-in-place orders have strained many businesses, and in some cases, governing bodies have been asked to shoulder that pressure.

Some industries are lobbying to lower carbon restrictions — claiming it’s a matter of survival. The International Air Travel Association has asked the International Civil Aviation Organization to lighten the standards that are part of the Carbon Offsetting and Reductions Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), adding the threat that some nations would pull out if the agreement isn’t amended.

Turns out, international climate commitments aren’t as fatal as airlines make them out to be. The Environmental Defense Fund’s statement responding to airline pressure reads in part:

“Coronavirus/COVID-19 is a global crisis that has hit public health and the world’s airlines are facing real economic and structural threats. But U.N. climate action is not one of them. That’s because there will be plenty of high-quality credits available to help airlines meet their carbon limits in CORSIA’s initial years – and because CORSIA includes provisions, thanks to ICAO foresight, that give airlines flexibility to deal with the COVID-19 crisis without sacrificing climate protection.”

Car companies have also done their share of lobbying. In Europe, automakers have requested that the European Union delay implementing tighter carbon regulations. In response, Greenpeace UK’s executive director, John Sauven, told The Guardian in part, “…it would be a mistake to use this crisis as a reason to roll back on environmental regulations. One, it won’t suddenly restart car sales, and two, tackling one crisis can’t be done at the expense of another one.”

Now is not the time to shirk the Paris Agreement goals

As governments do their best to control the spread of coronavirus with stay-in-place orders, individuals, businesses, cities and nations won’t be able to accomplish everything they have planned.

A message of compassion has been floating around the media to quarantined individuals — it’s ok to be unproductive right now. Parents who are homeschooling their children while working their normal nine-to-five, for one, should cut themselves slack. Multinational corporations that have received billions of dollars in stimulus funds, on the other hand, shouldn’t need slack when it comes to climate action.

The Nature study emphasizes that every country needs to increase its efforts to achieve the Paris Agreement’s target. The initial investment for G20 nations before breaking even is between $16 trillion and $104 trillion, the study finds. Benefits will require a long-term view, as the projected breaking even point is the year 2100.

Continuing climate mitigation, though, will enable nations to avoid an approximately 0.6 percent annual reduction in GDP due to the effects of climate change.

People may be seeing clearer skies out their windows as fewer individuals drive to work each day, but a few months of inactivity won’t exactly solve the climate crisis. Even as the coronavirus crisis creeps into summer, cities will have to grapple with the added challenges of climate-related flooding, wildfires and more, a Four Twenty Seven analysis shows.

There is serious work to be done, and now. Yes, there are economic benefits to be realized, but the consequences are harsher. We can’t afford to put off the Paris Agreement, and strict climate standards, until after the crisis ends.

Image credit: Nils Nedel/Unsplash

Handwashing Expert Myriam Sidibe Calls for 'Public Health Marketing' to Beat COVID-19

Myriam Sidibe spent more than a dozen years at Unilever, where she led the Lifebuoy brand's renowned global handwashing campaign. Engaging Lifebuoy, U.N. organizations and NGOs, and competitors like Procter & Gamble and Colgate-Palmolive, the campaign helped more than 1 billion people around the world improve their handwashing habits.

Called "the biggest hygiene behavior change program in the world," the campaign was also a driving force behind the creation of Global Handwashing Day, which raises awareness of handwashing to prevent disease. This work has already changed countless communities for the better, but perhaps it's never been more important than it is today. "Coronavirus is now bringing us global handwashing year," Sidibe told TriplePundit by phone from her home in Kenya.

Now on sabbatical from Unilever and a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, Sidibe is exploring a new discipline she calls "marketing for public health," which is meant to "infuse marketing with value" and "bridge the divide between what companies say and what companies do."

Detailed in her new book, "Brands on a Mission: How to Achieve Social Impact and Business Growth through Purpose,” this new realm of purpose-driven marketing is key to how companies can best respond to COVID-19, Sidibe says. "When you look at the reach of these manufacturers and the overall private sector, they’re sitting on grand resources and abilities to communicate to the public about how they can comply with what is required today, in a way that’s less scary and more influential," she told TriplePundit.

Marketing for public health: Re-tooling companies' best assets to respond to COVID-19

Sidibe further details her vision for purpose-driven marketing in an article published in Harvard Business Review last week, where she provides a five-step framework for brands to connect their purpose to their operations and drive impact. These range from winning internal support among leadership to the difficult exercise of measuring an initiative's effects on public health and wellbeing. When it comes to COVID-19, she outlined three key action items for business leaders during her interview with 3p.

Engage in responsible marketing. The traditional tools of marketers — including market research, product innovation, communications and incentives — can be leveraged for behavior change and improving public health, Sidibe wrote in HBR. "Brands have huge marketing budgets, and they are talking to the population," she told 3p. "The way I see this is that the private sector has a huge role in terms of incentivizing self-isolation and quarantine, handwashing with soap, and hygiene."

This role breaks down into two levels. "The first is access to essential hygiene products like soaps, sanitizers, masks and testing kits. The second is enabling people to use these products," she explained. "It's not just about distributing the soap. It's about making sure you come up with messaging that is dynamic, that changes and that enables a social norm around handwashing with soap. All of that is absolutely critical to make a real dent in stopping the crisis."

Join multi-stakeholder coalitions. To maximize impact on a global crisis like COVID-19, Sidibe advises brands to "join coalitions where they can bring their resources — not only cash, but also human resources and creativity — to the forefront of the conversation."

There are no shortage of options on this front. To name just two examples: Sidibe is working with former Unilever CEO Paul Polman and the coalition Business Fights Poverty on a campaign to accelerate local action and global best practice sharing across businesses as they seek to respond to COVID-19. Her book is also connected to a global movement, also called Brands on a Mission, to generate a collective US$1 billion investment in sustainable business models that address health and well-being.

Keep business continuity and resilience. Of course, every responsible business leader wants to leverage his or her resources to save lives and livelihoods amid the COVID-19 crisis, but maintaining their own operations is also important, Sidibe says.

"Obviously it doesn’t serve anybody if the community is collapsing. A lot of these businesses and companies are our employers as well as motivators," she told 3p. "In a moment like this, you can't just be thinking about your own business because you don't operate single-handedly. Yet we do have to keep business resilience and business continuity in mind, because we need them to keep bringing the goods to the public."

A focus on the most vulnerable is key to beating COVID-19

From her home base in Kenya, Sidibe has a unique vantage point from which to view the COVID-19 crisis. More than 27,000 coronavirus cases have already been identified in Africa, and it's spreading quickly. The World Health Organization warns the number of cases on the continent could surpass 10 million within six months.

"We cannot wait until the number of cases grows, because there is absolutely no way that our health infrastructure would be able to pick that up," Sidibe told us. Although Kenya is in a better position, some less developed countries on the continent have less than 50 ICU beds each, Sidibe says, putting their healthcare systems at grave risk of becoming overwhelmed. "At the core of the response has to be prevention and communication to enable these prevention mechanisms so we can contain this as much as possible."

But in densely populated environments where people work to eat each day, this is easier said than done. "The most vulnerable will be those who are not able to practice [social distancing] behaviors because of crowding," Sidibe explained. "You may have 12 people living in a single room. You don’t have a private toilet or private handwashing facilities. You have to share."

Further, "it’s very nice to tell people to stay home, but the reality is a lot of the economy is still driven by the informal sector. What people sell today is what feeds their families," she said. "So, prevention and livelihoods have to be absolutely synergized. You cannot talk about prevention without talking about livelihoods."

To best respond in the vulnerable communities where it matters most, brands can take initiative to distribute soap, sanitizer and masks, set up public handwashing stations, provide resources to frontline healthcare workers, and — perhaps most importantly — use their marketing resources to educate the public about how to keep themselves safe, Sidibe says.

"You need both the consumerism as well as the messages and the trust within communities," she told us. "If you combine market access as well as a community presence, together you can really get to a real impact."

On this front, she's also spearheading the National Business Compact on COVID-19, a national business coalition campaign in Kenya. "There is no way we can solve this crisis unless we solve for the most vulnerable," she said firmly, "otherwise the virus will always be here and therefore we will never be safe."

The bottom line: Now, more than ever, social impact is key to brand survival

In the age of COVID-19, brands not only have a moral responsibility to keep their stakeholders safe, but also a business imperative to act swiftly and meaningfully. "We’re in a moment of crisis, and the businesses and brands that do not think beyond their consumers to the communities and environments in which they operate will not be regarded very well," Sidibe says.

There's no one-size-fits-all solution to a corporate response, she concluded. But now, more than ever, companies have to be sure they do something. "Brands can do all sorts of things," she advised. "They can obviously make sure that we have the products available, but also they can also make sure the right behaviors are encouraged by mainstream media and mainstream marketing in ways which support the population, because this is a hard moment for everyone."

Image credit: Gallery DS/Unsplash

Across the Pond, More Signs of a Renewable Energy Renaissance

The economic recovery from COVID-19 will be a long and painful effort, and judging from recent developments, it may be especially painful for fossil fuel industry stakeholders. Policy makers in the European Union are beginning to coalesce around a strategy of fueling the COVID-19 recovery with renewable energy, and some of the world’s leading corporate citizens are on board with the plan.

They mean (renewable energy) business

Last week the energy advocacy group We Mean Business shared its powerful lineup of organizations in favor of renewable energy and green jobs, and it is impressive.

To start with, the chair of the EU’s committee on environment and public health launched the new European Alliance for Green Recovery. The public-private coalition started with a bang, including representatives from 37 global companies based in Europe.

The impact is bound to ripple across to the U.S., where many of these companies already have a profound influence on the sustainable business landscape.

The list includes Iberdrola, Enel, EDP, H&M, Ikea, Unilever, AB InBev, Nestlé and Volvo Group, along with the construction materials firm Saint-Gobain and the water and waste management company Suez Group.

“These companies understand the growing risks associated with climate change and are acting now to ensure they are able to minimize those risks and be more resilient to future shocks,” We Mean Business explains. “These companies also know that the decisions governments make now will lock in the strategic direction of entire economies for years to come.”

In addition to taking on energy-related carbon emissions, the group also demonstrates that other industrial sectors are part of the solution. Of particular interest is new technology under development by Alliance member HeidelbergCement.

More companies commit to more renewable energy and clean tech

We Mean Business also notes that additional companies have committed to the Science Based Targets initiative in recent weeks, despite the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. SBTi establishes fact-based pathways for businesses to meet the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

More than 850 companies have made commitments to SBTi or set targets, including some of the most recognizable names in North America such as Xerox, Whirlpool, Walmart, Verizon, Hershey, and Coca-Cola, among many others.

Other renewable energy coalitions have also seen growth in recent weeks. That includes three initiatives organized by The Climate Group, all of which have significant support from U.S. business leaders: RE100 (renewable energy), EP100 (energy productivity) and EV100 (electric vehicles).

EU leads on renewables; U.S., not so much

Among policy makers in the 27 EU Union countries, support for a “green recovery” after COVID-19 is not universal. However, the endorsement of leading businesses may provide enough momentum to swing enough votes in favor.

On April 9, Reuters reported that 10 EU environment ministers out of 27 member countries signed an open letter in support of a green recovery plan, including Sweden, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Austria, Denmark, Finland, Portugal, Latvia and Luxembourg.

“We should withstand the temptations of short-term solutions in response to the present crisis that risk locking the EU in a fossil fuel economy for decades to come,” the letter argues, “Instead, we must remain resolved to increase the EU’s 2030 target before the end of this year…and inspire other global players to raise their ambition as well.”

By April 17, France and Germany also signed on to the letter, which calls for COVID-19 recovery funding to include elements of the EU’s own European Green Deal plan.

The prospects for a national green recovery plan are less certain here in the U.S. The federal legislative process is controlled by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who has established a firm record of support for the coal industry (though not necessarily for coal miners) and other fossil fuel sectors.

So far, Senator McConnell has opposed efforts to steer stimulus funds in the direction of the wind and solar industries.

Nevertheless, many U.S. businesses are not waiting around to be inspired by activity in the EU. We Mean Business cites Barry Parkin, the Chief of Procurement and Sustainability for Mars, who affirmed his company’s ongoing commitment to accelerating climate action even while prioritizing COVID-19 response.

Parkin also neatly summed up the public health connection between COVID-19 recovery and climate action.

“We urge governments to ensure their plans to rebuild our economies prioritize the health of humans by keeping the health of the environment a core consideration,” he said.

That plea may fall on deaf ears in the office of the Senate Majority Leader, but state governors are certainly listening.

Key U.S. states, including New York and California, are continuing to sprint ahead with their renewable energy plans. Senator McConnell has slowed down progress, but he can’t stop it.

Image credit: Aniek Wessel/Unsplash

Mattel Joins the Bioplastic Toy Brigade

Toys, whether they are in the real or digital world, sure can help us get our minds off the day-to-day reality with which we’re now coping. And as is the case with many sectors, the toy industry will have to consider a reset once we emerge from this crisis. To that end, Mattel announced this week it would start manufacturing some of its timeless children's toys out of plastic derived from sugarcane.

It’s okay to put it in your mouth — these toys are made from sugarcane

These toys, which include the brands we remember from our youth (or that of our kids), include Fisher-Price’s Rock-a-Stack and Baby’s First Blocks. The revamped versions, which Mattel put on pre-sale just in time for Earth Day, follow on the heels of the company’s announcement several months ago that it would transition both its toys and packaging to 100 percent recycled, recyclable or bio-based plastic by 2030.

The toy giant also says it surpassed a 2018 goal of transitioning to 90 percent recycled material for its paper and wood packaging. At last check, Mattel’s packaging currently consists of 93 percent recycled paper or wood fiber.

Sustainable plastic is a challenge for the likes of Mattel and Lego

Mattel’s foray into bio-based plastics is welcome news. We will certainly need to find a way to manage the proliferation of single-use plastics as retailers ditch their reusable bag policies and consumers load up on bottled water during this crisis. And as the growth of medical waste surges, we also must confront the possibility that our waste streams could be disrupted over the next several months.

Just because we face a surge in plastic waste, however, doesn’t mean that we can expect supply chains to turn on a dime. Lego is one company that has faced its share of challenges while it soldiers on toward a 2030 goal to use 100 percent recycled materials in its iconic building bricks. The company said it took about two years to find a way to make those green bushes and trees in some of its building sets out of a more sustainable polyethylene.

But Lego, and its customers, expect those bricks to maintain their long-term durability and vivid colors — and they’ve got to remain stuck together, too. No one wants to buy a $100 Burj Khalifa set and have it risk crumbling or see the colors fade. “The company makes more than 3,700 individual elements,” explained Wired’s Brian Barnett in 2018. "It uses 20 different kinds of plastic to make those bricks, tires and adorable [mini figurine] helmets. And as many as 80 percent of Lego pieces consist of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene, or ABS, a petroleum-based substance that polyethylene can't hope to replace."

And while some environmentalists have been quick to point their fingers at toy companies for their contributions to plastic waste, let’s not forget the social benefit of a set Fisher-Price building blocks or a box of Legos — there are certainly far worse toys out on the market from a manufacturing or child development perspective.

Thinking out of the box — literally

Educational Insights, which dates back to 1962, is also rethinking how its toys are packaged. Its Design & Drill toy line includes an age-appropriate truck for which the packaging becomes part of the assembly process — in turn, helping to reduce waste. The toy’s design also offers another way in which the company can further its educational mission.

“Toys typically have been the opposite of sustainable — inexpensive, breakable, tossed aside when fads change, and most of the time made entirely of petroleum-based plastic,” Forbes’ Joan Verdon observed earlier this year. She’s right, but as is the case with the fashion sector, another industry critics view as wasteful, toy companies big and small see the writing on the wall (or toys on the floor): They are hearing from their customers, and they are shifting how they do business.

Image credit: Mattel

Fashion Industry Seeks a More Sustainable Direction Amid This Crisis

Fast fashion has received significant press coverage during the coronavirus pandemic, but not for the reasons that manufacturers and retailers within the fashion industry would prefer.

“Fast Fashion Is Being Left In The Slow Lane: Why The Days of Cheap Clothing Might Be Over Forever,” declared a recent Forbes headline.

“‘It’s Collapsing Violently’: Coronavirus Is Creating a Fast Fashion Nightmare,” warned another headline, this one in GQ.

Situations like the current crisis in Bangladesh, the world’s second largest ready-made fashion exporter, increasingly demonstrate the human, environmental and economic downsides of the current fast fashion market.

Garment factories across Bangladesh have reported more than $3 billion in cancelled and postponed orders due to decreased demand stemming from COVID-19. Ready made goods make up more than 80 percent of Bangladesh’s total exports, so these unpaid orders could have catastrophic implications for the Bangladeshi economy and population.

What will happen to the more than 2 million workers (and, subsequently, families) affected by the factory closures and unpaid paychecks as Bangladesh’s garment factories close in response to these cancellations? What will be done with the 980 million items of clothing produced but now left without a destination?

Fortunately, new initiatives are signaling progress in sustainable fashion.

As Andrew Busby wrote in the aforementioned Forbes article:

“Prior to the coronavirus pandemic … the direction of travel was beginning to shift away from mass fashion consumerism and brands were having to re-think their business models for 2030 and beyond. That kind of timeline now seems laughable. Most felt that this process would take years, but what the coronavirus has done is to shrink what might have happened in years to just weeks."

Here are three ways the fashion industry can take advantage of this new accelerated timeline to improve sustainability and prevent future supply chain catastrophes like those in Bangladesh.

Know and respect each link within the supply chain

Companies with strong relationships to suppliers are more likely to keep commitments to them when crises should arise. One way this can be done is through local manufacturing partnerships. Another way is through clear, open lines of communication. Jane Mosbacher Morris, founder and CEO of apparel brand To The Market, told Vogue Business that she has been talking with her suppliers to get a stronger understanding of their needs. She’s hosting an upcoming webinar to provide suppliers within the fashion industry with resources to stay viable in the current business climate.

“There are creative ways to support everyone in the value chain, and it takes effort to figure out what that looks like given your constraints,” Mosbocher Morris said in the article. “My ability as a CEO to support myself and my team is probably stronger than the garment workers’ ability to support herself and her family.”

Embrace circular fashion

The circular economy is having quite the fashionable moment. Retailers ranging from Patagonia to Puma have introduced circular initiatives this year, and the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) has named circular fashion its “2020 Earth Day Focus”. So what does circular economy in fashion mean? It means that organizations must create apparel and production systems “that maximize the value of healthy materials through multiple cycles of use before reprocessing them into new raw materials of equal or greater quality at their very end of life.”

Some analysts say now is an excellent time to work toward circularity in the fashion industry. The production of garments worldwide has paused while many employees are working from home; how consumers view their apparel needs in the long run could change dramatically.

Brands can begin by brainstorming ways to reinvent the overstock clothing currently waiting in warehouses and stockrooms throughout the COVID-19 lockdowns. For example, McKinsey & Company’s State of Fashion 2020 Coronavirus Update suggested organizations breathe new life into current stock through efforts like apparel personalization, improved customer experience, and reorganization of the fashion calendar to accommodate current stock into later seasons.

Collaboration is key for the future of the fashion industry

The McKinsey & Company report also encouraged fashion companies big and small to work together: “This will also be a time for collaboration within the industry—even among competing organizations. No company will get through the pandemic alone, and fashion players need to share data, strategies, and insights on how to navigate the storm.”

One way companies can collaborate is through shared manufacturing sites and resources. The tech startup Unmade’s software allows brands like New Balance to “rent” blocks of manufacturing time on a specific machine at a factory according to product demand, rather than reserving a factory run for the entire order at once, often resulting in product surplus. On-demand manufacturing also allows flexibility. Orders scheduled to run in Indonesia, for example, were moved to U.S. facilities when the novel coronavirus first closed factories in Asia.

Virtual industry events are another way for key players in fashion to collaborate while maintaining social distancing. This week’s Fashinnovation 2020 featured more than 80 speakers focusing on how the industry can better respond to the current COVID-19 pandemic while also implementing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Through these efforts and more, the fashion industry can emerge more sustainable than ever following the COVID-19 crisis. As Guardian writer Tamsin Blanchard wrote in a March article: “The cycle of fashion for fashion’s sake has been broken. We must use this time to rethink how this industry can be redesigned with respect for the planet and the health of the people who work in it.”

Image credit: Unsplash

After COVID-19, We Can Go Back to Normal, or Move Forward

The COVID-19 pandemic will long be a defining event for younger generations - much as the Great Depression, the Kennedy assassination, the moon landings and the housing market crash of 2008 affected society for years. People lament missed graduation ceremonies (mostly those who remember their own fondly) but there are other lessons that may be even more compelling. Rather than seeking to turn back the clock a few months, let us do so thoughtfully, carefully and fully implementing the lessons we can take from this unintended and unexpected experience we find ourselves facing.

Environmental stewardship won’t go away after COVID-19

Over the decades, the gradual increase in air pollution has lowered visibility in many of our cities. Even with reductions due to lower-polluting vehicles and the shift away from coal-fired power plants, it is still stunning to see vistas that most of us never remembered before. The swiftness with which the cleaner air has revealed the natural beauty of clearer skies has been remarkable. Will we lament the loss when, inevitably, locales reopen as the threat from the novel coronavirus fades? Or will we seek to ‘hang on’ to what we had forgotten we had lost and seek to maintain the benefit even as the economy comes back online? The bottom line: will we seek to hang on to what we have forgotten we had lost?

Social justice disparities have been magnified

COVID-19 has demonstrated the foresight of those who built the Internet; they demonstrated the importance of building a redundant and resilient system that handled the increased traffic and dependency. It also demonstrated the need to make sure that access to this critical infrastructure reaches to every community and every home. Some counties in North Carolina, for example, made the decision not to reopen schools and offer distance-based learning because a high percentage of their students would have been left behind.

Rather than creating disparities, they chose to offer only review for the balance of the school year. That is not a sustainable solution, as those disparities exist all the time. Now that COVID-19 has made that lesson clear, will we learn? What will we do differently? Or will we simply accept going back to what has been exposed as being unfair?

Similarly, the great economic boom of the last decade has left all too many behind. After missing one or two paychecks, millions of people were desperate for economic relief and assistance, whether through unemployment benefits or checks. Some countries offered a substantial portion of salary, tax relief and payments. Clearly the soaring stock markets and political rhetoric did not match the experience of many people and their families. Now that such a stark reality has been exposed, do we accept going back to the way it was?

Another social aspect from sheltering in place: will some choose to continue to telework and will companies be more receptive, especially if they maintained productivity and costs were reduced? What does this portend to the dual-income-family and issues like child care? What will the long-term impact be on our roads and public transit, if fewer people use them? Will people be inspired to travel themselves, if fearing potential exposure and backlash on social media? The answers will emerge after a long time, only for more questions to arise.

Sound corporate governance still matters

COVID-19 has revealed to many companies that team spirit does not rely on proximity to be created; nor does proximity offer enough of it. Leaders who never, or rarely met with their subordinates may have felt, or been compelled, by these circumstances to communicate and check in more often via conference calls and videoconferencing). Will they go back to their old management style, or move forward?

Finally, the importance of being able to influence without authority has been demonstrated. That is something sustainability professionals have had to do for years – how do you build productive relationships with those whom you need to be on board, when you don’t have the authority to do anything by lacking the opportunities to ask, discuss and persuade?

We have learned that in order to thrive, we must have established relationships so that the first time you reach out to someone, you’re not asking a stranger for a favor. Building credibility by demonstrating a shared purpose as well as an understanding of their goals and situation are lessons that politicians will need to have learned sooner rather than later. After all, reopening “for business” is going to take collaboration, cooperation and coordination. And that starts with mutual respect and trust.

In the words of Thomas Paine; “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” To do otherwise would only compound this ongoing tragedy.

Image credit: Victor He/Unsplash

Think Earth Day Doesn't Matter in the COVID-19 Age? Not So Fast

The 50th Earth Day has eerie similarities to the first one that millions of citizens observed a half century ago. In 1970, the U.S. was divided over the Vietnam War, but growing concern over environmental degradation pushed an estimated 20 million Americans to demonstrate peacefully for reform. A week later, President Richard Nixon escalated the war with the invasion of Cambodia, and protests erupted across college campuses nationwide. Days later, a demonstration at Kent State University in Ohio ended in violence, with the shooting deaths of four unarmed students.

The momentum surrounding Earth Day at first appeared to fall back into the rearview mirror, but all was hardly lost. In the following years, the U.S. Congress passed a dozen major environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act.

Now, we face similarly dark days, and again we're confronting a tipping point. There’s no shortage of evidence suggesting the novel coronavirus pandemic, and future disease outbreaks, have and will continue to have links to climate change. Society in turn faces a host of challenges: the proliferation of single-use plastics, rethinking our approach to food waste, surging deforestation, and the lack of environmental justice within our most vulnerable communities.

Sure, we may feel some optimism from being able to see the mountains for once from our neighborhoods. We’ve also fawned over the photos of marine life returning to the canals of Venice. But the Earth’s climate risk trajectory hasn’t changed, and in any event, the current clean air and sights of wildlife roaming in our neighborhoods have come at the expense of economic collapse and human despair.

At some point, we’ll have to rebuild our economy, but we must find a way to do so while we strike a balance with nature. I’ll give you one reason: Of the top 150 prescription drugs in the U.S., about three-quarters of them are derived from plants. The bottom line is that if we want to stay healthy, the planet must be resilient, too.

"As we inch from a ‘war-time’ response to ‘building back better,’ we need to take on board the environmental signals and what they mean for our future and wellbeing,” wrote Inger Andersen, head of the U.N. Environment Program, “because COVID-19 is by no means a ‘silver lining’ for the environment.”

Here’s the reality: At some point, the curve will finally flatten, and we can take baby steps back toward the way of life we once knew. But we’ll need to work even harder to ensure our planet can sustain life far into the future.

From the Brands Taking Stands newsletter. Be sure to subscribe!

Image credit: Sergio Souza/Unsplash

COVID-19 Fallout: A Temporary Relief for Plastic Bags

The 50th anniversary of Earth Day is saturated with ironic twists as the COVID-19 pandemic wreaks its history-making path of havoc across the world. One example is the impact the novel coronavirus has had on efforts to reduce the use of single-use plastic bags. Here in the U.S., concerns over infection may have motivated some jurisdictions to suspend, reverse, or relax hard-won bans on plastic bags. The question is, is this a temporary setback or a new chance at life for the petrochemical industry?

COVID-19 and bans on plastic bags

There are some good indications that the setback is strictly temporary, and simply delays the inevitable.

New York State is a good case in point. The state is an epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S., so it is reasonable to assume that state officials are particularly sensitive to the potential for enabling the virus to continue spreading.

Coincidentally, a newly passed statewide ban on single-use bags went into effect on March 1, just as the virus began to take hold. As reported by Sophia Chang of Gothamist, the ban was supposed to be enforced starting on May 15. However, last week the New York State Supreme Court delayed that starting date until June 15.

If that sounds like good news for single-use plastic bag stakeholders, it’s not. The Supreme Court directive was not motivated by concerns that the single-use plastic bag ban would enable COVID-19 to spread. It was simply because the courts in New York are closed in order to adhere to the state's social distancing guidelines.

As the Albany Times Union reported, the Supreme Court directive grew out of a lawsuit brought against New York by a plastic bag manufacturer.

“Because the courts have all but closed down due to the coronavirus pandemic, both sides in the suit agreed to hold off enforcing the ban until June,” the Times Union explained.

Similarly, the COVID-19 outbreak has had an impact on some recycling programs, as government offices and facilities have closed for all but essential functions. In other words, the mere fact that some jurisdictions have rolled back regulations against plastic bags is not evidence of concern that reusable or paper bags involve a greater threat to public health.

Plastic bags: do they protect against the spread of COVID-19?

In fact, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, which is responsible for enforcing the ban, has continued to carry guidance on keeping reusable bags clean and sanitary on its website, as does the New York Department of Health.

The ongoing concern, virus or not, is bacterial cross-contamination between meat and produce. That is not a matter specific to reusable bags, as it could occur if different items are commingled in a single-use plastic bag as well.

On April 10, well into the New York outbreak, the state’s Department of Agriculture also provided detailed guidance for grocery stores on preventing COVID-19 infection. Providing single-use plastic bags to customers did not make the list.

Chang also cites two academic health experts who back up New York’s position on the use of reusable bags during this time.

Similarly, on March 26, Canada’s CBC News interviewed a health expert who noted that reusable bags were not considered a risk factor, and that shoppers should wash hands in order to help contracting or spreading COVID-19 regardless of what bag they use.

The defense of single-use plastic bags

Nevertheless, the plastic industry’s stakeholders and supporters have been quick to portray single-use plastic bags as a preventive measure against COVID-19, compared to reusable bags.

For example, on March 12 the publication City Journal carried an article arguing that reusable bags spread “deadly viral and bacterial diseases” including COVID-19. City Journal, though, is produced by the think tank Manhattan Institute, which bills itself as a “leading free-market think tank” and has received substantial funding over the years from the Koch brothers.

The article was written by City Journal contributing editor John Tierney, whose work for the publication is characterized by criticism of government-sponsored science.

In a 2016 article supporting the presidential campaign of then-candidate Donald J. Trump, for example, Tierney wrote that President Obama’s appointees to the CDC and FDA “used junk science—or no science—to justify misbegotten crusades against dietary salt, trans fats, and electronic cigarettes.”

Turns out, bags not made from plastic may be safer after all

Despite the lack of evidence for any impact on public health, some grocery stores may still prefer to provide single-use plastic bags for their customers, in order to avoid having their employees handle items that shoppers have brought from home.

That is a matter of employee relations, and it is understandable considering how much is yet to be known about how COVID-19 spreads.

Somewhat ironically, though, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 17 actually indicates that if anything, plastic bags may involve measurably greater risk than cloth.

The study demonstrated that the novel coronavirus was detectable on a plastic surface for up to 72 hours, a significantly longer period of time than on copper or cardboard surfaces — though in any case, barely any of the original virus remained on any of the surfaces tested.

Nevertheless, in a letter to U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar dated March 18 and obtained by Politico, the Plastic Industry Association pushed back, asking the agency to “speak out against bans on [plastic] products as a public safety risk and help stop the rush to ban these products by environmentalists and elected officials that puts consumers and workers at risk.”

Plastics after COVID-19

Despite the reference to risk, the science does not support the Plastic Industry Association’s case.

Just as importantly, the demographics do not support it, either.

The all-important Millennial generation — which spans younger adults who are more likely to survive the COVID-19 virus — is also the largest group currently contributing to the waste stream, and the least likely to recycle according to some studies. However, the Millennial generation is also increasingly focused on environmental stewardship and zero waste as a lifestyle.

If single-use plastic bags are a symbol of the consumer response to the COVID-19 crisis, then it is all the more likely that once the immediate crisis is past, reusable bags will become the symbol of recovery, and a symbol of the movement toward a more healthy and sustainable future.

Image credit: Peter Uetz/Wiki Commons

1970 Earth Day Organizer: 'Election Day Should Be the Real Earth Day in the U.S.'

(Image: An estimated 50,000 people gathered at the University of Michigan on March 11, 1970, for "Give Earth a Chance," the first known event affiliated with Earth Day.)

Fifty years ago today, activists across the U.S. and around the world staged mass demonstrations, rallies and teach-ins in observance of the first Earth Day, held on April 22, 1970. A year earlier, Denis Hayes was a 25-year-old graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, but he dropped out after one semester to lead a grassroots movement that would ultimately become the Earth Day Network, the primary organizers of the first Earth Day.

Although the nation was being torn apart by the Vietnam War and still reeling from the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., evidence of environmental degradation — from the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill to Ohio’s infamous Cuyahoga River fire — had become too significant to ignore, Hayes recalled during a webcast hosted this week by the climate action network We Don't Have Time.

"In the backs of people's minds was the recognition that breathing the air in major American cities was very much like smoking two packs of cigarettes a day. Rivers were catching on fire and species, even our bald eagle and California condor, were going extinct for reasons relating to pesticides as written in 'Silent Spring,'" he told attendees from more than 130 countries on Monday. "We had literally dozens of issues suggesting that as we got richer and richer, our quality of life was getting poorer."

On Earth Day, an estimated one in 10 Americans gathered to "demand changes in the way the country does business," Hayes said — and they got it. Mere months later, the Clean Air Act passed unanimously in the U.S. Senate and with only one dissent in the House of Representatives. It was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on the final day of the year.

"For the next 10 years, we were almost unstoppable," Hayes remembered. "The Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Toxic Substances Control Act, the Superfund Act, the National Forest Protection Act, the Environmental Education Act — it just went on and on for 10 years. We began to restructure the country."

Of course, the United States is a very different place today than it was 50 years ago. We've come a long way in some respects — the air in major cities is cleaner, waterways and forests are legally protected, and biodiversity has returned to corners of the country where it was once feared to be lost forever.

But in many ways, we've regressed. Advocates have continually tried and failed to put climate action on the national agenda, as the current administration holds firm in its decision to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement. The march toward corporate personhood, culminating in the 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision, has put unprecedented political power in the hands of corporations. Some have used it for good, but many have not.

Hayes, now 75, and his colleagues at the Earth Day Network envisioned this year's festivities as a massive call-to-action to once again shift the direction of environmental and climate policy in the U.S. Then, of course, came the novel coronavirus.

"COVID-19 basically took two years of organizing and turned into a massive belly flop," Hayes said, lamenting the disruption in activism that accompanies the humanitarian tragedy of the pandemic. "Where we wanted to have 750,000 people on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., it would now be illegal to have more than 10 people together."

In an op/ed published in his hometown newspaper, The Seattle Times, Hayes offered a bold suggestion in response: Let’s make Election Day Earth Day.

(Image: A 100,000-person “human traffic jam” on Fifth Avenue in New York City on April 20, 1970.)

Election Day: "The real Earth Day in the U.S."

"A big part of what we were trying to do with Earth Day this year was to catapult climate to be one of those issues that you vote on," Hayes said. "For most Americans, there are a dozen issues out there that you're considering, but there are one or two or three that if the candidates are wrong on that, you simply will not support them. Climate has never been that kind of an issue in a presidential race."

But it can be, Hayes insists — and if it is in 2020, great things are possible. He pointed to massive policy shifts around renewable energy in China as evidence of what political impetus can achieve.

"When China decided to get into solar energy, it made no solar panels at all. It set on a program, and 10 years later it was making more solar panels than the rest of the world put together. It had driven the cost down from about $30 a watt down to today, at utility scale, about 25 cents a watt," he explained. "You can set these things up, come up with policies to get there and then, if you're genuinely committed, bring about heroic change."

The Earth Day Network will host virtual teach-ins, social media campaigns and voter education drives over the next five months leading up to Election Day on Nov. 3. In his op/ed published earlier this month, Hayes called on everyone to be a part of the solution.

"If you have never walked precincts for a candidate, volunteer to do it as soon as travel restrictions are lifted. If you have never raised money for an inspirational candidate in a tight race, do it now. If you have never participated in a get-out-the-vote drive, November 3 is the day you should prepare for," he wrote. "On November 3, don’t vote for your pocketbook, or your political tribe, or your cultural biases. This November 3, vote for the Earth."

Click here to take the Vote Earth pledge and get involved.

Image credits: University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability/Flickr and Bettmann/CORBIS via Tommy Japan 79/Flickr