Employee Engagement Key to Sustainability for Tech Networks of Boston

Editor's Note: This is the second post in a three-part series featuring Tech Networks of Boston. In case you missed it, you can read the first post in the series here.

In part one of this series, we described how this small, Boston-based professional information services company has built sustainability into its strategy from its inception in 1994 with a commitment to making its own operations as resource-efficient as possible.

Founder and CEO Susan Labandibar understood that engaging her employees in the company’s sustainability strategy would be critical. From the beginning, she has adopted a hiring process that ensures staff additions share her passion for maximizing human and environmental resources, and maintained a commitment to building a culture that maximizes the value generated by its human assets. “This commitment is a key element of a genuinely sustainable business strategy,” Labandibar stated.

However, the obvious benefits of this type of strategy are frequently overlooked or even ignored. Supported employees who feel that they are fairly treated, enjoy their work environment, and appreciate what the firm stands for in its approach to customers, the community in which it works and the natural environment are more productive in their work and remain with the firm over a longer period.

Employee retention is significant in financial terms. The cost of finding, hiring and training professional staff is estimated by human resource management firms to be 1.5 times the base salary of an employee. This measure does not include the lost productivity or the negative impact on clientele due to staffing shortages.

Landibar has learned that it is not a given that employees will embrace the principles of sustainable business. If people are feeling uncomfortable about some aspect of the business, that is not the time to bring up a new sustainability-focused initiative. Moreover, employees like to feel that a proposed sustainability initiative is relevant to the company’s business in some way; an effort to engage her staff in the plight of Orangoutans “backfired,” according to Landibar, because the staff couldn’t relate to it. “We have continued to evolve the program so that staff honestly feel as if they are part of the efforts,” she says, “and that these are efforts they can be proud of.”

TNB has employed many of interns over the years and made a point of utilizing them in the early years to be the point persons for both internal and community-focused sustainability initiatives. It was not until 2006 that the company formally brought on a sustainability specialist.

Landibar is a firm believer that small businesses have a key role to play at the local level in helping each other to understand the clear benefits of sustainable business practices. She has used her own experiences and leveraged TNB’s employees and interns to find ways of communicating this message to other local business and other organizations. This effort has resulted in the creation of several startups to further drive specific messages on the value of sustainability in the local business community. These startups include:

- Climate Action Liaison Coalition (CALS), which works with small and mid-sized businesses to build internal, metrics-based, sustainable businesses; acts as a political advocacy platform; and works to foster strong ties to local communities.

- Southie Trees, an environmental initiative aimed at preserving and maintaining trees in the South Boston area.

TNB has never had a formal Green Team but is now making use of CALS to, for example, help establish a baseline and metrics tracking system for a variety of sustainability parameters as required by their recently achieved B Corp status.

Another example of how TNB seeks to engage others in the local business community in the value of sustainable business practices is its series of IT Roundtables for non-profit organizations. There is a strict company policy that meat is not served at these roundtables or other company functions. This policy ensures any waste is wholly compostable, supporting one of the firm’s core principles of treading lightly, and demonstrating to others how they can do the same.

Part 3 of this series will show how sustainability has been a key factor in helping TNB identify new business opportunities and expand its revenues. Stay tuned!

Image courtesy of Tech Networks of Boston

Target’s 'Made to Matter' Collection Boasts Expansion of Sustainable Products

Large retail chains are no longer putting sustainability on the back burner. Within the last five years, big brands have been pursuing bold moves to stake their claim in complying with growing customer demand for quality products with a socially driven or environmentally sustainable mission attached.

Such is the case for brand giant Whole Foods that in 2012, introduced an ingredient certification process for all of the personal care products it sells. Walmart is equally pushing the sustainability needle on its offerings, having recently made headlines for its latest venture to offer cheap, organic food products across 4,000 stores.

Following suit is retail giant Target, which recently unveiled its latest move toward expanding sustainable, organic and natural product offerings. Housed under its “Made to Matter—handpicked by Target” program, 120 new organic or natural health, wellness, grocery and beauty products will roll out to all of Target’s 1,754 stores over the next several months. The collection promises to make it easier to find products made with simple, recognizable ingredients with unbeatable prices.

“Almost all of our guests, 97 percent, say they buy some product that is natural, organic or sustainable,” Kathryn A. Tesija, Target’s executive vice president for merchandising and supply chain told The New York Times. “They’re looking for products in this category,” she said. “We’re making it easy by calling them out.”

The new program is the result of a unique collaboration between Target and brand CEOs who came together nearly two years ago to push the envelope on retailers meeting the needs of customers who shop with a conscience.

Seventeen brands are included in the Made to Matter Program and consist of: Annie’s Homegrown, Burt’s Bees, Chobani, Clif Bar & Co., Ella’s Kitchen, EVOL, Horizon Organic, Hyland’s, Kashi, Method, Plum Organics, Seventh Generation, SheaMoisture, Target’s Simply Balanced, Vita Coco, Yes To and Zarbee’s Naturals. Participating brands, many of which are currently offered at Target, will introduce an exclusive item for six months.

Not only does this move make organic and sustainable products much more accessible to current Target customers with an affinity for eco-conscious lifestyle brands, but it also has the potential for Target to boost sales in a rapidly growing category for the chain.

Made to Matter will also serve as a launching pad for the introduction of sustainable spins on everyday products, such as Seventh Generation’s release of their first bleach-free cotton baby diaper. Select products will be available on Target.com and through Target’s mobile app.

Image courtesy of Target

Social Enterprise Alliance Summit 2014: Day 1

By Robbie Hall

With 405 registered attendees and 37 represented social enterprises, the Nashville Social Enterprise Alliance Summit '14 began with a tremendous start. This year’s theme, “Connecting For Purpose,” aimed to create person-to-person engagement and interaction at every step. With tools like Pathable, attendees could stay up to date on the speaker directory and event schedule, and connect to a community of other individuals who are ready to produce massive social impact through successful social enterprises and networking.

Whether being motivated while listening to a dozen of our colleagues share during the Spark Stories session or having our eyes opened with new solutions to old problems in the workshops and keynotes, there was no lack of inspiration at this event. Constantly, I found myself scrambling to put pen to paper and absorb the wealth of knowledge and advice given by industry leaders who were offering a new way of seeing the economy.

One such session that stood out to me was “The Solution Revolution” with Bill Eggers, Javier Flaim, Elizabeth Schwan-Rosenwald and Jim Fruchterman. In the session, these thought leaders hit on a repetitive theme and topic of the day -- which was finding a new perspective, a new lens, a creative way to conquer an existing problem.

Bill Eggers, author of “The Solution Revolution,” focused on this by honing in on tough societal problems, as well as citizens and social enterprises, and how they are relying less on government-only solutions. Instead, we are seeing more weight leaning towards the solution economy perspective. Bill took us through the example of traffic congestion. Traditionally the response might have been to invest in more or new roads, in additional bus services, or the introduction or extension of mass transit services such as subways.

The solution economy perspective however presents a range of other options that collectively offer an emerging congestion relief system. Elements include:

- Ridesharing (facilitated by services such as Carma or Carpooling.com)

- Car-sharing (such as services as Car2Go or Zipcar)

- Bike-sharing (e.g. Capital Bikeshare)

- Personal travel assistant apps

- Mobile parking apps (such as San Francisco’s SFpark)

- Real time traffic management and tracking

- Telecommuting

- Integrated fare management.

While these solutions may not fully ‘solve’ the issues, they do greatly relieve the pressure and reduce the costs associated with traditional methods.

A further example he shared was that of Dean Kamen’s Slingshot water purifier. Dean developed the purifier in the private sector, but ultimately he had trouble finding partnerships with global health institutions, so instead partnered with Coca-Cola to bring it to those most in need. “By 2015, Coca-Cola and partners plan to bring 100 million liters of clean, safe drinking water to 45,000 people across 20 countries.”

Bill explained that through the solution economy perspective, we need to look differently at who we could partner with to achieve our goals, not just the traditional avenues that we might have intuitively relied on in the past.

To Javier Flaim, of Recyclebank, this meant finding a better way to recycle waste and engage a community. Now we are not talking about the proverbially sense of waste as in an earlier post but instead the physical sense. Think landfills and garbage bins full of items that could and should be recycled but somehow never are. What new way of thinking can help solve this crisis that is so damaging to our planet?

The solution comes from the company's creative method that helps create a more sustainable future by rewarding people for taking everyday green actions with discounts and deals from more than 4,000 local businesses and national brands. The company empowers individuals to make a collective impact on the environment by increasing household recycling and taking other environmentally-friendly actions. The company made it measurable, adding sensors to the trucks so that they know exactly how many pounds are loaded onto the truck and recycled house-to-house and community-to-community.

“Recyclebank has a rich history of innovation and environmental impact. Over the years, we’ve seen that while recycling is often the gateway into sustainable behavior change, our more than four and a half million members are eagerly looking for new ways to deepen their commitment to a greener lifestyle,” said Flaim.

Elizabeth Schwan-Rosenwald offered some critical insight as well -- not in the sense of physical waste but through pro bono. She sets the strategy in the creation of a thriving pro bono marketplace in each city. Typically you would not think of the social enterprise sector as the pro bono avenue, but by changing the way you look at an existing issue and adding some new perspective we find a powerful tool to create social impact.

"Pro bono is the key to changing how the social enterprise sector looks at problem-solving. When strong pro bono resources are in place the result is a flourishing sector that has the supports necessary for growth," said Schwan-Rosenwald.

For example, she mentioned Hilton, who is considered first in class in regards to hospitality. Hilton approached her with an offer to provide their expertise in hospitality as a pro bono service. Not the typical thought when it comes to pro bono but a game changer if we wrap our minds around the concept. What if industry experts, in development, design, implication, delivery and almost all fields, offered up their knowledge and experience as a pro bono service to the social enterprise and non-profit sector? The end result would be astounding social impact and change fueled by the leaders of these industries, companies who are already doing it right and ready to share that knowledge with others who want to make a difference in this world.

Image courtesy of the Social Enterprise Alliance

Video Interview: Justin Bakule; Exec. Director, Shared Value Initiative

Every Wednesday, TriplePundit takes 30 minutes or so to chat with an interesting leader in the sustainable business movement. These chats are broadcast on our Google+ channel and embedded via YouTube right here on 3p.

Today, TriplePundit’s Founder, Nick Aster, spoke with Justin Bakule, Executive Director of the Shared Value Initiative.

Justin is responsible for the overall strategic direction and management of the Initiative, and works closely with major corporate, civil society, government and academic stakeholders in order to track and influence the development and capture of shared value research, the shared value idea in practice, and the growing global community of practitioners.

WATCH THE LIVE INTERVIEW RECAP BELOW.

Many viewers around the world chimed in to the conversation on Twitter with #3pChat!

If you missed it, you can learn about the Shared Value Initiative right here or on our YouTube channel.

About Justin:

Justin led FSG’s thinking about how to build a shared value field first through the launch of the Shared Value Leadership Summit in 2011, followed by the development of the Shared Value Initiative business plan and partnership development process. These efforts led to the formal launch of the Shared Value Initiative as a 2012 Clinton Global Initiative Commitment to Action currently supported by leading shared value organizations around the world. Justin is also an experienced public speaker having addressed executive teams, industry organizations, and academic audiences around the world on shared value and the role of the corporation in society.

Justin came to the Executive Director role with over 15 years of experience advising corporations, foundations, nonprofits, and governments on issues of strategy and performance management. He has played a leadership role in FSG’s shared value consulting having worked with Mars, Inc. focused on improving cocoa production in West Africa and rice production from the Mississippi Delta. He has also advised Arauco, a leading Chilean forestry company, and Mercy Corps, a leading international NGO on their shared value strategies. Justin was in the Peace Corps as a small enterprise development volunteer with the Malian Ministry of Tourism in Gao, Mali.

Seafood Traceability Makes for Better Products and a Healthy Bottom Line

The environmental benefits of seafood traceability are obvious: By tracking a fish through the entire supply chain – from capture to plate – you can ensure the fish wasn’t caught using illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices. But many companies, like Norpac Fisheries Export, are discovering that traceability is also good for their bottom lines.

When Norpac set up an electronic tracking system in 2002 to monitor the fish it captures and sells, the company wasn’t trying to certify its seafood as sustainable, Norpac’s Managing Director Thomas Kraft says; the goal aim was to develop a tool to better manage the flow of the company’s product. It was only after the system had been in operation for a few years that Kraft realized it could help the company follow fish through the supply chain -- essentially creating a reliable audit trail for its product -- and guarantee its seafood was not captured using IUU fishing methods.

Under Norpac’s monitoring system, fishermen tag each fish with a barcode and record information about the vessel and the catch while offloading their boats: species, weight, and time and location of capture. Some of the company’s boats are outfitted with radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags; on these ships, fishermen wrap a Velcro strap with a RFID chip around each fish’s tail. Norpac’s RFID reader connects to a vessel monitoring system, which allows the company to identify where fish were caught within a few hours of capture, Kraft says. To further verify the ship’s catch, government observers document each fish caught once a boat lands and corroborate their records with vessel log books.

During the processing stage where fish are broken down into their component parts, processors assign barcodes for each part of the fish and tie the new codes back to the fish’s original barcode, Kraft says. Each of the four loins of a tuna will have a separate barcode, for example. To authenticate the company’s traceability data, Kraft says Norpac works with third-party auditors FishWise and MRAG Americas.

Is such a thorough tracking system time-consuming and labor-intensive to implement?

“It actually saves us time and money,” Kraft says. “It’s a value add to our business.”

Fish is a highly perishable product, so it’s invaluable for a fishing company to know what product it has in a timely manner – information a fish tracking system can provide, Kraft says. If a company doesn’t know its inventory, product tends to idle in storage, losing freshness and potentially ending up unsellable and wasted. On the other end of the spectrum, a company may short customers and lose a sales because it didn’t realize it didn’t produce enough product.

“There’s less waste [with our traceability system],” Kraft says. “It improves efficiency and our utilization of the material.”

Following fish through the supply chain can also improve customer service, according to Kraft: If a customer has a question about product it purchased, Norpac can track the fish’s barcode to quickly identify the issue and where in the chain it happened – a process that used to take days, now takes hours, Kraft says.

Businesses should also look at traceability as a risk mitigation tool, Kraft says, to protect their financial liability or prevent public relations crises.

“If [a store, restaurant, etc.] is buying fish from a company, and it comes out that they have IUU fishing in their supply line or use slave labor on their boats, that’s going to reflect poorly on [the buyer],” Kraft says.

But can traceability translate to higher profits? Can a fishing company using sustainable fishing practices fetch a higher price for a fish that it can track through the supply chain and demonstrate its environmental credentials?

“It’s not enough to say fish is moving toward sustainability,” Kraft says. “Customers appreciate that, but they don’t feel like they want to pay more for it.”

According to Kraft, a fully traceable fish, caught in an environmentally responsible way, doesn’t necessarily command a higher price, but it can attract new customers and open doors to new opportunities in the marketplace. However, he says, a company may be able to charge more for sustainable seafood if they can promote its excellent quality, proving that the fish is fresher and was in transit for a short period of time, for example.

Michael Carroll, vice president of the fisheries and aquaculture division at environmental consulting firm Vertex, agrees that sustainable seafood doesn’t always yield higher profits in consumer markets, citing a lack of peer-reviewed studies that show U.S. consumers will spend more on sustainably caught fish. But many studies indicate that consumers already pay more for high-quality fish from premium locations, such as lobster from Cape Cod, says Carroll, also a co-founder of BackTracker, a database system that helps companies follow fish through the supply chain and validate their data against government records.

Without a grounded traceability system, fishermen will struggle to see market premiums flow back to them through the market, Carroll explains. If a fishing company can verify the origin and attributes of the fish, using a traceability system like BackTracker, it has the opportunity to reap the higher price its product commands in the marketplace, he says.

“If a fisherman produces a high quality product from a premium location but doesn’t have the ability to pass data [about the fish’s capture] through the supply chain, he has no chance to get a higher price for that fish,” Carroll says.

In general, Carroll says that traceability – combined with a system to authenticate its data – should increase the value of products from most fisheries that strive for food safety, sustainability, quality, premium location or other “desirable attributes,” depending on the consumer and market.

Look Twice, Buy Once: Sustainability Through Consumer Restraint

By Mark Paigen

There are many angles to sustainability in the fashion/apparel world.

- Fair trade companies seek to create good living conditions for underserved populations by providing first-world markets for developing world labor.

- Use of organic fabrics and materials lessens the impact of industrialized agriculture with its heavy dependence on petrochemical fertilizers.

- Recycled polyester from beverage containers is perhaps the most eco-friendly fiber, yielding a smaller environmental footprint than organic cotton.

- Domestic manufacturing minimizes trans-oceanic transportation costs and seeks to bolster local economies more than global ones, creating a sense of community along the way.

- Lifecycle analysis provides impact transparency of a product from cradle to grave, a much more comprehensive picture than the discrete burden of the manufacturing process.

Each of these initiatives has value, merit and positive outcomes. All of these efforts need further energy and attention as our collective footprint becomes heavier. All should be championed, celebrated and expanded.

There is however, a more fundamental issue to be addressed. I am reminded of my early days backpacking when the lure of innovative new products inspired more than a few to carry “a hundred pounds of lightweight backpacking gear." Overconsumption of organic/recycled, fair-trade clothing is still overconsumption.

Ultimately, we must all learn to buy fewer things, repair them as we can, and recycle, upcycle or compost them when we are finished. Today, the average American purchases 64 garments each year. Between 1980 and 2005, American clothing consumption increased five times. Purchases have risen because fast fashion, with an ever-moving style target, pushes consumers to continually buy more clothing.

The shift to shopping as recreation rather than necessity and the emergence of clothing cheap enough to throw away has also made a big impact. Fashion is big business, and nobody needs as many clothes as are produced each year. Companies need to promote new styles to keep demand strong. The largest companies, Zara, H&M etc., have become experts at creating demand through style changes, churning out millions of pounds of cheap clothing -- most of which is tossed out before it wears out. High-end fashion produces far fewer garments, but is often predicated on the idea that last season’s style is outdated and unsuitable for today’s wear.

The return of some classic, durable styles for men (raw denim, heavy flannel shirts, heavy leather work boots) seems like a positive direction towards durable goods, but the effort will be wasted if the lumberjack look of today is out of fashion next fall. When was the last time you mended a garment, patched a hole, resoled a shoe? It is fashionable to wear clothing that was worn out before it was sold, but unfashionable to wear clothing that you have worn a hole in. How backwards is that?

Zoom out yet again, and the picture is not just about fashion, it is about a “growing economy." The success of any nation’s economy is measured in percent growth, with consumer spending driving the majority of this growth. The equation looks like this: More stuff sold = more stuff built = more jobs and a better standard of living.

Unfortunately a corollary equation is: More stuff sold = more stuff built = more pollution + fewer resources + more trash

I am not an economist, but there has to be a better way. We live on a finite planet, with finite resources, and growth cannot continue without environmental degradation. We must learn to produce a better life for everyone on this planet without constantly producing more “stuff.” Perhaps we need a “Quality Revolution," a major cultural shift where quality becomes our holy grail and we all purchase half as much stuff for the same amount of money.

My first company, Chaco, produced sport sandals that were distributed through specialty outdoor and footwear retailers. We made the most durable sandals on the market and were the only American company that resoled their sandals. We paid our employees not to drive to work and to quit smoking. We shared profits and sponsored substantial philanthropy. And yet we were always cognizant of the bottom line -- we made garbage. Without a material separation/recycling/composting program, everything manufactured is ultimately trash.

My second venture, Osmium, concentrates on domestic production, quality construction and a brand message to look twice and buy once. The footwear that we are working on will all be resolable and re-buildable. As a serial entrepreneur, I am stuck between that rock and a hard place – striving to build better product, trying to educate towards less consumption, yet ever aware of the impact of our products.

Image credit: Cam Morin/Unsplash

Mark Paigen is founder and CEO of Osmium, offering high quality menswear to guys who look twice and buy once.

Global Renewable Energy Investment Drops, But Installed Capacity Rises

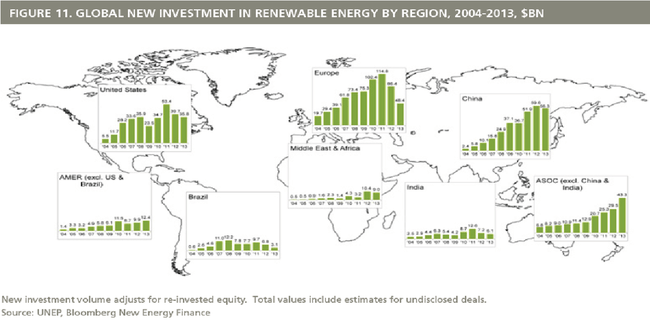

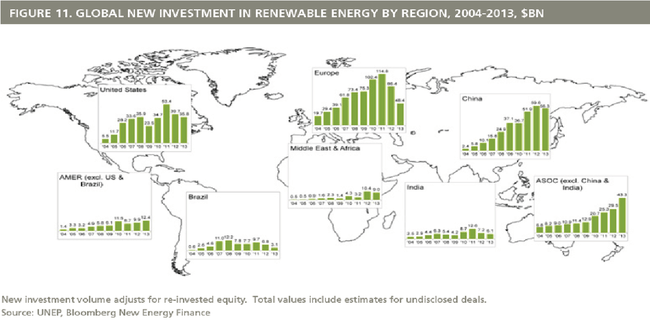

Renewable energy investment fell year-over-year in 2013, down 14 percent, but the drop belies some heartening news for market participants and clean energy supporters. In short: Renewable energy's share of overall power generation continues to grow, and more renewable energy generation capacity is being brought online at much lower cost, solar energy generation capacity in particular.

According to the latest global renewable energy annual report from the Frankfurt School-United Nations Environment Programme Collaborating Centre (FS-UNEP) and Bloomberg New Energy Finance, global renewable energy investment totaled $214 billion in 2013, a second consecutive year of decline and 23 percent below a 2011 peak. Even so, renewable energy accounted for 43.6 percent of new power capacity, while renewable energy's share of worldwide electricity generation rose to 8.5 percent from 7.8 percent in 2012.

There were several other reasons for optimism regarding the outlook for renewable energy, according to FS-UNEP-BNEF's, “Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2014.” For one thing, some 1.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions were avoided as a result of renewable power generation last year. But that's not all.

Solar and renewable energy: A virtuous cycle

Reductions in the installed costs of solar, wind and other renewable energy systems is driving a virtuous feedback cycle, with wind, solar and other renewable energy systems now competitive, or cheaper, than conventional fossil fuel-fired electricity generation in a growing number of countries and markets.

Solar energy investment did fall sharply in 2013, down 20 percent to $114 billion year-over-year. Other developments across the solar energy value chain illustrate how the confluence of advances in technology and manufacturing, along with a little help from supportive government policies and regulatory frameworks, is now being leveraged to greater effect by private and public sector organizations around the world, however.

Sharply lower costs for solar photovoltaic (PV) systems drove installations to a record-high 39 gigawatts (GW) in 2013, according to FS-UNEP-BNEF's latest report. More solar PV capacity was installed last year than in 2012 (31 GW) and for less money, the report authors highlight.

Another positive development in the solar energy sector was improved profitability for manufacturers, whose profit margins – despite record-high demand – were being squeezed to, and beyond, the point of insolvency and bankruptcy. This had a two-fold knock-on effect for the share prices of clean energy companies -- which staged a 54 percent recovery -- and prompted a surge in public share offerings on stock exchanges.

Wind energy investment fell just 1 percent worldwide last year, to $80 billion, and there were some strong positive signs looking ahead. Of particular note, even on an unsubsidized basis, installing new wind power capacity is now cost-competitive with the lowest cost fossil fuel-fired (typically coal) electricity generation, if not even cheaper, in a larger number of countries around the world. And that's not even considering the other benefits and advantages of wind energy, such as its zero-fuel cost, zero running greenhouse gas emissions and essentially zero water use.

Investment in geothermal energy development was the only renewable energy sector covered in the report (large-scale hydroelectric is excluded) to rise in 2013, increasing a sharp 38 percent to $2.5 billion. Biofuel investment dropped 26 percent to $5 billion, the lowest tally in nine years, while that for biomass and waste-to-energy systems fell 28 percent to $8 billion. Investment in small hydroelectric (less than 50 MW) dropped 16 percent to $5 billion.

Emerging markets driving renewable investment growth

In large markets around the world, Europe's investment in deploying renewables tumbled 44 percent to $48 billion and China's, though down 6 percent to $56 billion, surpassed Europe's for the first time. U.S. renewable energy investment dropped 10 percent to $36 billion, while Brazil's dropped 54 percent to $3 billion -- its lowest since 2005. India's renewable energy investment fell 15 percent to $6 billion, according FS-UNEP-BNEF's report.

Regionally, renewable energy investment for the Asia-Oceania region excluding China and India surged 47 percent higher, to $43 billion, with Japan's investment in renewable energy shooting 80 percent higher to $29 billion excluding R&D. Renewable energy investment in the Americas excluding the U.S. and Brazil also rose, gaining 26 percent to reach $12 billion.

Uncertain economic and regulatory outlooks – including initiatives to curtail the construction of new fossil fuel-power capacity and reduce CO2 emissions – also contributed to a decline in fossil-fuel power generation investment in 2013. Yet, even amidst the rising frequency, intensity and costs of extreme weather events and atmospheric CO2 measurements surpassing the 400 parts per million-level, investment in fossil-fuel power generation still exceeded that for renewable energy in 2013.

Renewable vs. fossil fuel-power investment

Including large-scale hydroelectric power, investment in renewable energy capacity, at $227 billion, came in below gross investment in fossil-fuel power, which came in at $270 billion, the report authors highlight. When factoring out fossil-fuel-power replacement investment, investment in renewable energy was about double, however.

Accounting for a growing share of worldwide power generation capacity and new additions, more consumers, businesses, governments and public sector organizations are recognizing the vital, and increasingly valuable, benefits rapid deployment of renewable energy brings to economies and societies. More can, and needs, to be done, however, according to renewable energy proponents.

As the world's preeminent multilateral organization, the United Nations (U.N.) is working to increase the momentum behind renewable energy's development and growth.

Writing in the foreword to the FS-UNEP-BNEF report, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon stated,

“To expand on these trends, we need better policy mechanisms, more public finance and more private investment. That is why, on 23 September 2014, I am convening a Climate Summit at United Nations Headquarters in New York.

The Summit will engage world leaders at the highest level – from governments, business, finance and civil society – to catalyse ambitious action on the ground as well as accelerate political momentum for a universal, legal climate agreement.”

The U.N. Secretary-General went on and said the Climate Summit “is an opportunity for public and private actors to rise to the challenge and work together in a ‘race to the top’ to develop the policies and solutions that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support adaptation and resilience.”

Image credits: FS-UNEP Collaborating Centre-BNEF, "Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2014

Fuzzy Math on Pennsylvania Fracking Jobs

Incumbent Republican Gov. Tom Corbett of Pennsylvania has been campaigning for re-election on a platform that touts the 200,000 jobs created through his support for natural gas fracking, but the Pennsylvania fracking boom is not all that it's cracked up to be. A provocative article newly published in The National Journal casts some serious doubts upon Corbett's representation of the number of jobs created by fracking, an unconventional method of extracting natural gas from shale formations.

The National Journal makes a good case that the fracking industry accounts for less than 1 percent of current Pennsylvania job creation, which gets us to thinking that the number of jobs actually created by the Pennsylvania fracking industry is offset by the jobs at risk in the state's rich and varied historical tourism, recreation and agricultural sectors -- all of which are threatened by fracking operations.

A brief history of fracking

For those of you new to the subject, here's a quick review. Fracking is short for hydraulic fracturing, an unconventional method of extracting oil and gas by injecting a chemical brine into shale formations.

Fracking is not a new technology as far as drilling operations in sparsely populated areas of the western U.S. are concerned, but it only erupted into cross-country boom status after 2000, under the Bush/Cheney administration.

In recent years fracking has spread far beyond the West to encompass populated areas on both coasts, the Midwest, Appalachia and other inland northeastern states including Pennsylvania.

With millions of gallons of water involved in a typical modern fracking operation, you would assume that fracking would be covered by the Clean Water Act, but that is not the case.

Then-Vice President Dick Cheney successfully won an exemption for fracking from the Clean Water Act back in 2005, leaving the oil and gas industry free to drill thousands of fracking wells across the U.S. with virtually no federal oversight.

In Pennsylvania, a patchwork of inadequately policed state regulations and local zoning rules have filled the gap, with predictable results on local water resources.

Adding to the impacts is the common practice of injecting spent fracking brine into existing, unused oil and gas wells, leading to additional hazards including earthquakes in areas that were formerly free of earthquakes.

Though not affecting Pennsylvania as of yet, a series of brine disposal and direct fracking-related earthquakes in neighboring Ohio has given industry watchers fresh cause for concern.

Pennsylvania, fracking and job creation

The National Journal article is a must read (here's that link again), but for those of you in a hurry here are some of the tidbits from reporter Clare Foran.

Let's cut straight to the mustard. Midway through the article, Foran debunks the significance of direct fracking-related job creation in Pennsylvania:

The energy boom has injected fracking—and energy jobs in general—into the gubernatorial race, but its role in the political discussion dwarfs the sector's actual impact on the state economy: In 2012, jobs in core industries tied to natural-gas production made up less than 1 percent of Pennsylvania's total 5.5 million jobs.

Leading up to that point, Foran unpacks Gov. Corbett's misleading use of state employment statistics.

As Foran reports, Corbett cites a figure of over 200,000 jobs supported by the shale fracking industry.

However, Foran uncovers a Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry report that breaks that down to just over 30,000 jobs "closely connected" to fracking.

The remaining jobs, as Foran confirmed with Corbett's campaign, pop up in a state study of the fracking supply chain. However, that study includes a number of industries with a connection to fracking that Foran characterizes as "tenuous at best."

In particular, Foran cites the construction industry, which is booming in Pennsylvania whether fracking is happening or not (see this recent federal BLS report for details).

The pace of fracking job creation in Pennsylvania has also tapered off sharply in recent years, as the gas market has become more competitive and the boom edges closer to a bust.

Speaking of competition, while Pennsylvania has less than ideal wind resources the wind power industry in that state actually ranks fairly high compared to other states, and it is beginning to grow into permanent wind-related manufacturing facilities as well as the installation of new turbines.

Fracking vs. tourism

The state's tourism sector is also far outstripping fracking in terms of job creation, whether direct or indirect. The Pennsylvania Tourism Office posted this nuggest about the 2012 travel year:

Travel Industry Leading Job RecoveryThe total number of leisure and hospitality jobs in Pennsylvania rose to a new, record-high 521,000 jobs in 2012, with a 2.1 percent growth rate that was three times the 0.7 percent increase in the state's total of nonfarm jobs.

To support that trend, last year a bipartisan group of state legislators proposed creating a new, independent Pennsylvania Tourism Commission, complete with a $3 million marketing budget and $15 million in tax credits.

In that context, pushback against the fracking industry in Pennsylvania will most likely gather steam, and Gov. Corbett's support for that industry could hurt his campaign more than it helps.

Image credit: Flickr/dfb photos

The Quick & Dirty: A CEO. A Leader. Sometimes We Need a Bit of Both.

By Henk Campher

I participated in another great Twitter chat with Aman Singh from CSRwire and Nick Aster from Triple Pundit hosting Aron Cramer from BSR, Nigel Topping from CDP and Peter Graf from SAP.

One of the many interesting side discussions I had was with Christine Bader, John Friedman and a few others about how CEOs say they want to lead when it comes to sustainability but most of them are completely absent in the debate. There are leaders -- like Elon Musk from Tesla, Sir Richard Branson from Virgin, Craig Jelinek from Costco and Blake Mycoskie from TOMS -- who have taken up very vocal and thoughtful leadership roles. But in most cases, CEOs say they want to lead but go completely missing when it comes to substance. They give us the usual "it is in our DNA" nonsense and jargon and lack substance to back it up. Sometimes they even give us the "our employees are our greatest asset" baloney.

When we are lucky these empty words will give us lots of hot air for a little while, but many CEOs aren't willing to take up true leadership. To lead is to suffer the consequences of leading; to sometimes have to take people (consumers, investors, employees, etc.) to places they do not want to go. That is what leadership requires -- brave and bold like a Star Trek captain who will "boldly go where no man has gone before." Unfortunately most business leaders are just plain missing in action and hiding behind the soft and cozy walls of "investment community." That isn't leadership. That is the yes-men mentality that has taken hold amongst too many leaders.

Novel idea: To be a thought leader you need a thought -- and you need to lead. A bit of both please.

That is why I love those true business leaders out there and why we need to go out of our way to applaud them. It is so easy to go back into the comfy offices and focus on the next quarter or lead on soft issues. Or hide behind some lobby group or business association that lobbies for less regulation and lower taxes or deny climate change. Do not blame the public when they don't trust businesses or when consumers shout "greenwashing." True leadership is undermined by those leaders who fight the issues that are important to society -- fair taxes, less business subsidies, decent wages, climate action, etc. Every time a business leader speaks out against these issues or are caught with their hand in the pocket of a politician or lobbyist, the reputation of business in general takes a knock. Don't blame the consumer. Blame your CEO. Not enough businesses are showing them that they can be trusted. Ask yourself -- how does your leader rate amongst CEOs?

We need to support those leaders who are willing to step up and speak out. But we also need to make it possible for them to speak out against other business leaders. Those business leaders hiding in dark offices or behind interest groups undermine true business leadership. And they undermine the interest of business in general. The public doesn't have the voice to speak out, and the media is too soft on these business leaders. We need business leaders to speak out. We need heroes -- business heroes.

True leaders tackle tough issues and build companies for today AND tomorrow. They build sustainable businesses. True leaders don't shy away from the tough issues they face today and the tough issues they will face tomorrow. And true business leaders will point to those "leaders" who undermine confidence in business and reject their voices and their business models -- loudly and vocally. They will remind us of who the true leaders are -- those who lead. True leaders are never afraid. True leaders have courage, and they lead.

I leave you with this quote from one of my personal heroes and one of the great modern leaders, Nelson Mandela, "There are times when a leader must move out ahead of the flock, go off in a new direction, confident that he is leading his people the right way".

Image credit: Flickr/opensourceway

-

A series of quick & dirty opinion pieces by Henk Campher. Senior Vice President, Business + Social Purpose and Managing Director of Sustainability at Edelman out in the Wild West of San Francisco. Disrupter of purpose. Engineer of big ideas. Slayer of myths. Social media junkie – @angryafrican. He never wears ties. Ever. But always wears an accent with a strategy and opinion in his back pocket. Please note this series will not focus on individual companies and any reference is purely to provide color commentary.

Follow Henk Campher on Twitter.

Shell Joins Pledge For Drastic Cuts In Greenhouse Gases, But...

Last week, the Royal Dutch Shell company got a lot of nice publicity for signing the Trillion Tonne Communiqué (TTC), a climate action project of the Prince of Wales' Corporate Leaders Group. However, when we took a quick look at the group's FAQ page and put that together with a news item from our friends over at TheHill.com, two things jumped out at us: coal and carbon capture.

When you put coal and carbon capture together with TTC, the most you can say about Shell is that the energy company is using the declaration more as publicity leverage for its existing oil and gas operations, rather than a meaningful step toward transitioning its business model into renewable sources. So, let's take a closer look at TTC and the answers to those frequently asked questions (FAQs).

The Trillion Tonne Communiqué and coal

Here's TTC describing itself:

The Trillion Tonne Communiqué is a global call to arms from businesses who take the science of climate change seriously and are demanding a proactive policy response.

Now, let's take a look at the Communique itself (you can download it as a PDF here after selecting your language). Skip down to the section on the specific steps that TTC recommends to bring down greenhouse gas emissions (break added):

Create a plan for fossil fuels, especially coal. Achieving net zero emissions will require substantial changes to our energy supply ... the scale of demand for fossil fuels means we will only be able to continue to use them if the emissions can be captured and stored.This is particularly true of coal, which, although abundant and cheap, is also the energy source associated with the most carbon emissions. New investment plans must take this into account.

TTC focuses on coal rather than weighing in with equal urgency on all fossil fuels. The answer to FAQ No. 6 elaborates on that point (break added):

We cannot manage the risk of climate change successfully if the world continues to expand unabated coal use.However not only is coal the fossil fuel that is associated with the most carbon emissions, but there is also a growing international effort to make a strategic shift away from the burning of unabated coal.

FAQ No. 6 further elaborates by providing examples of aggressive anti-coal policies that are already in the works.

That includes the World Bank and the European Investment Bank, which have announced that they will limit their investment in coal plants.

FAQ No. 6 also cites President Barack Obama, who announced the end of U.S. public financing for new coal-fired power plants overseas. Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden are among those signing on to Obama's call for other nations to join the ban.

Clearly, TTC is not an across-the-board action plan for fossil fuels. It aggressively zeroes in on coal as the low-hanging fruit of climate action policy, leaving oil and gas off its radar for now.

That's perfectly legitimate as far as picking off the low-hanging fruit goes, but it also makes TTC a climate policy safety zone for oil and gas companies like Shell, enabling them to burnish their green cred without substantially altering their business model.

Shell and carbon capture

The absence of movement on Shell's business model becomes even more obvious if you take a look at the aforementioned news item from TheHill.com.

Following up on the addition of Shell to the list of TTC signatories, reporter Laura Barron-Lopez got this email statement from a company spokesperson (emphasis added, and here's that link again):

We recognize that over the long term, net global emissions must trend towards zero. Both of our New Lens Scenarios show that this objective can be realized by the end of this century, but not without action by governments to stimulate changes in the energy system and considerable deployment of carbon capture and storage.

We're not sure what Shell means by "changes in the energy system," but the reference to carbon capture and storage is a definitive statement of business as usual: Shell will continue to sell oil and gas, other folks will continue to burn it, and other folks will have to figure out how to deal with the emissions.

TTC and great publicity for Shell

As for the publicity Shell has been getting out of signing on to TTC, that article from TheHill.com was headed "Shell joins ranks in fight against climate change."

Echoing TheHill.com was a story in the Guardian, which put Shell in the same company as the highly regarded Unilever as far as climate action goes.

The article sourced a BusinessGreen.com piece titled "Corporate giants' 'Trillion Tonne Communiqué' issues fresh demand for climate action."

It's easy to see why Shell put an excerpt and link to the Guardian article in a prominent position on its home page. Here's the headline, subhead, photo caption and opening paragraph as it appears on TheGuardian.com:

BT, Shell and corporates call for trillion tonne carbon capTrillion tonne communiqué signed by 70 companies calls for rapid response to rising emissions, reports BusinessGreen

A trillion tonnes of carbon must stay in the ground to stop dangerous climate change, say 70 companies with a combined annual turnover of around $90bn.

Unilever, Shell, BT, and EDF Energy are among 70 leading companies today calling on governments across the globe to step up efforts to tackle climate change. The companies, which have a combined turnover of $90bn, say the world needs a "rapid and focused response" to the threat of rising global carbon emissions and the "disruptive climate impacts" associated with their growth.

That's what you get when you cherry-pick a climate action group that best fits in with your current operations, rather than adopting a policy position that requires fundamental change.

Image (cropped): Shell gas station by Martin Abegglen