Q&A: Andrew Winston on Climate Risk, CSR and His New Book 'The Big Pivot'

It seems the topic of resilience is coming up more and more on the heels of the latest three-part report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Pundits, business leaders and journalists are asking questions like: How can we keep up with an increasing population? What does the threat of climate change mean for our society, and how can we remain resilient? Is it possible to prosper in a resource constrained world?

These are just a few of the issues addressed by author, speaker and consultant Andrew Winston in his new book, "The Big Pivot." While most conversations surrounding resilience to climate change and resource constraints end in hypotheticals and not much else, Winston's argument is concise and constructive. In less than 300 pages, he not only breaks down the risks businesses face in a changing world, but also provides clear direction on the strategies and tactics that will help companies meet these risks head on.

I had a chance to speak with Winston, who also advises some of the world’s biggest companies on environmental strategy, about his new book--and the mega-challenges that are on everyone's minds.

TriplePundit: When did you decide this was a story you wanted to tell and this was the time you wanted to tell it?

Andrew Winston: It was after Hurricane Sandy in the fall of 2012 that I felt that I really wanted to say something more than I've said before. I hadn't written a book for a few years at least; "Green Recovery" came out in 2009. And I just felt that the science has been getting harsher and clearer over the last couple of years. It was pretty clear already, but it got clearer. Then with things like Hurricane Sandy--and that was a personal thing because I was in the middle of it in Connecticut--the urgency kind of hit me. I kind felt like we're running out of time--that the impacts of climate in particular are right now, and the resource constraint stories were starting to really pop up as well. These two related mega-challenges were just kind of taking over and becoming serious threats to our society.

I felt that all of my previous work--or most of it, "Green to Gold" in particular--was telling the story of why green was good for business: what works and what doesn't when you're trying to go green and how to think about value creation. And those are all really important things, but that in a way tells you which direction you need to head. It doesn't tell you how fast you need to go, and it doesn't really challenge business at a fundamental level. It kind of still basically works within normal business framework.

So, I thought with the stuff that's happening now, there's just no way that the way we operate--the way business runs--is going to handle this. It was a bunch of things coming together and realizing that we're not going as fast as the science says. And that's starting to really paint a dire picture for society and for business, which people forget sits within society--not the other way around.

3p: Your first mention of a 'big pivot' moment is the metaphor of a wake-up call for someone to lead a more healthy lifestyle--maybe a doctor noticed high blood pressure or high cholesterol, shocking the person into action. For someone who hasn't read your book, what does the 'Big Pivot' mean for business, and why is it important?

AW: I use the metaphor in the book of health warnings--that you don't want to wait until you actually have the heart attack to start changing your behavior. The equivalent is that we're getting these warning signs: We're getting high blood pressure readings; we're out of breath as we try to chase a ball around; we're getting these danger signs.

It's always challenging to ask: Why now? Well, because it's getting too late to do it later, which is knd of the macro answer. But at the micro level, there are a lot of companies I work with where the signals they're getting are very real and very impactful--the cost of doing business is rising pretty dramatically. General Mills in their last quarterly report said that due to the extreme winter they lost 62 days of production ... and this cost them a significant amount for their earnings for the last six to nine months.

This is the time because the costs are starting to hit, but it's not so devastating that we don't have the resources to react. We're getting those warning signs, but we're not having the heart attack yet in most businesses. So, now is the time to get healthier before things get ugly ... It's challenging. You're talking about strategic choices and looking past this quarter, and that's very hard for companies to do--which is why I spent a lot of time on short term-ism in the book.

3p: Speaking to that, in practice, how would this 'Big Pivot' affect a company's bottom line in the short and long term? Is the holdup the fact that these changes are too expensive?

AW: It depends on what we're talking about. There's a whole range of things companies do that save money very quickly--and a lot of money, and a lot of energy and a lot of carbon. The story I tell about Diageo is the perfect example because it's both short and long: They cut their carbon by 75 to 80 percent in North America, and they cut 50 percent of that all through low- and no-cost initiatives. That's not only not prohibitively expensive--it's good business; it's the opposite of prohibitively expensive. Then they took the leadership choice to take another 30 percent of their footprint down by investing in landfill methane from a place near one of their Canadian facilities.

So it's not expensive. That's the big myth. The point is that it's getting increasingly expensive to not do this. If resource prices keep rising as they do, then not getting more material efficient, not building a circular economy, not finding ways to de-materialize, is going to get more expensive ... There are always going to be investment choices, but that's why I have a couple of different chapters around valuation and about asking what we mean by 'return'. What do we mean by 'expensive,' and what's the value we're creating? Even if we do things that cost more up-front, there's a whole bunch of value that we don't measure currently in business. If you're not measuring value right, you're underinvesting in the things that create value.

3p: How can we create value around these hard-to-measure resources? Will we ever get there?

AW: That's the biggest challenge. I talk in the book about two different categories of things that we don't put numbers on. [First is] the natural capital, and we're getting better and better at putting numbers on that. There are some really good economists and NGOs working on it, and there are some basic estimates of what it costs society. But getting that into business? Until it's actually priced in the marketplace--priced by either regulation or by self-regulation--it's just so hard to see why a company is going to take it into account. The other category of indirect value includes things like employee retention, risk reduction or resilience, or a hedge against fuel prices.

What's changing is these challenges are getting so big and so systemic that the things that [were once] external are becoming internal. Climate change is not some theoretical cost of carbon down the road, it's a hurricane destroying part of New Jersey. There's a physical, actual cost. And when you talk to Dow [Chemical Co.] and these companies that are trying to put numbers on natural capital, they believe there will be a price on it; they believe it's coming. They're not sure how, but they believe there will be regulation.

3p: In addition to describing a hotter and more resource constrained world, you also describe a more open world--there really isn't anywhere for a company to hide anymore. Can you speak to how transparency plays into all of this?

AW: Very little is hidden anymore. Everything gets captured. The data that we're collecting on all of our lives, all along the value chain in business, is growing. I talk about that in the book and give the example of the apparel supply chain, and what's different now is that the connections are easier to make. When there's a factory collapse, almost instantly everybody knows which companies have any association with that factory. Even if they're subcontractors, that comes out immediately: 'This is a Walmart subcontractor to a subcontractor," even before Walmart knows it in some cases.

The next generation of workers and consumers increasingly expect to know everything about a product if they want to: What's in it? Where was it made? Who made it? Were they paid a living wage? There are just higher expectations of getting answers to those questions, and I think in business-to-business relations it's even more pointed. Companies are asking for more and more data from their suppliers and just expect it to be transparent--to be given out the world, not just to them.

The way i think of it--and I may not say it as clearly in the book as I've thought about it since I wrote it--is that the transparency really is the multiplier. The mega-challenges are the climate and the resources; the transparency is just this lens over the whole thing, so there's nowhere to hide. We're not there yet, but we're getting closer and closer to much better information about every step of the way.

3p: Another thing that really struck me was your emphasis on partnerships--partnerships with government, partnerships with competitors, partnerships with advocacy organizations--relationships that many companies would otherwise never consider. Why is this crucial to the 'Big Pivot'?

AW: To me it's all related. The example I use in the book that I love is Coke and Pepsi working together--just because they are known as the biggest rivals, and they've been working together for a number of years on refrigerants.

When you think about it, all these things come together. There's a growing acceptance that we have a huge climate problem and a desire to find the biggest places we can reduce carbon or CO2 equivalent, so in that industry [they recognize that] refrigerants are a big problem. That comes from better data, better understanding, better science. It becomes more transparent over time as [companies] start to calculate their footprints. Then they identify and say, "Well, we need scale." That's part of the 'Big Pivot' is that it's big. We need scale to shift refrigerants, and we can't do this alone ... So we have to go find partners.

That's the part of the whole story that's really optimistic. You're seeing more and more of these pretty effective partnerships come together as companies realize that there's this notion of the pre-competitive--that they can ask themselves: What are we really competing on? I think that's kind of the interesting and cool question.

3p: You also touch on the need for science-based targets. Can you speak to the difference between a the typical sustainability goals we see from companies--cut GHGs by 10 percent by 2030, reduce energy use by 20 percent by 2017, which are often arbitrary--and setting an intentional, science-based target?

AM: The difference is fundamentally an internal versus external reference point. We normally set goals based on "What do we think we can do?" versus "What do we have to do based on the outside? What does the science tell us?" ... [To bring back] the equivalent of health again: Once you get that diagnosis from your doctor that you have to lose 50 pounds, you have to get your blood pressure down to reduce your heart risk, all of a sudden it doesn't really matter anymore that: "Well, I think I can lose 5 pounds." You now have to go by what the science is telling you. If you look at the PwC numbers or the McKinsey numbers, all based on IPCC, we need to get reduced carbon intensity of 6 percent a year. That adds up pretty quickly--that means that by 2020 you need to be on a path to 36 percent lower carbon intensity from here.

I will say that I was surprised in putting together the PivotGoals site [a free database available online here] -- we now have the 300 biggest companies in the world in there -- that there were many companies with goals on some key issues that were aligned with science. More than I thought. It wasn't enough, but I just thought kind of anecdotally that there were very few because very few companies say specifically, "We tied this to IPCC." Some have done it, I've discovered, without really saying it publicly. When they say "we want to cut 50 or 80 percent by 2050," they're looking at the science.

3p: What do you hope companies, executives and business leaders will take away from your book

AW: A few things: An understanding of the mega-challenges and a sense of urgency about them; a kind of inspiration or belief that the business community can play an enormous role and profit from managing these issues. [It all boils down to] an understanding of the problem and a belief that we can make the pivot--that we have the tools and that it will be profitable for the business and for all of us in a larger sense.

Third is the actual tools: the strategies and tactics that do something. That's actually most of the book. So, that's what I really hope [readers] walk away with is a to-do list: things they feel like they can walk away and do.

Click here to learn more about "The Big Pivot" or to snag a copy for yourself. PivotGoals, a free database of the environmental, social, and governance targets set by the Fortune Global 500 companies, can be found here.

Based in Philadelphia, Mary Mazzoni is a senior editor at TriplePundit. She is also a freelance journalist who frequently writes about sustainability, corporate social responsibility and clean tech. Her work has appeared in the Philadelphia Daily News, the Huffington Post, Sustainable Brands, Earth911 and the Daily Meal. You can follow her on Twitter @mary_mazzoni.

Solazyme Produces Algae-Based Lubricant for Cleaner Drilling and Fracking

When it comes to fracking, I am a NIMBY. I would prefer that it not be done anywhere near where I live, due to a number of concerns, primarily involving threats to the water supply, as well as concerns about methane leakage and even earthquakes. Yet, I knowingly consume natural gas to keep me warm and keep my lights on. As I do, I am grateful that most power no longer comes from coal, due to the enormous threat to climate stability posed by the large-scale coal burning that has taken place throughout my lifetime.

Of course I am a big fan of clean energy and efficiency, but I also recognize the fact that our society has come to its present state on a very rich energy diet, one that renewables alone cannot provide. Someday, perhaps they will, but that is likely decades away. In the meantime, how do we proceed? Even as we transition to cleaner and more efficient technology, the world’s population continues to grow, as do a number of very dynamic emerging economies.

Natural gas produces roughly half the amount of CO2 as coal. Because of this, unless the carbon can be safely and effectively captured, we will want to eventually move away from gas as well. But since it is both cleaner and readily available (via fracking), it is widely considered the logical choice as a bridge fuel. Let the buyer beware however. I have previously cautioned that shale wells tend to give out quickly and will prove far more costly in the long run than what we are looking at now.

However, reluctant to fully embrace “new nuclear” without a sizeable list of legitimate post-Fukushima concerns, that leaves me close to an indefensible position. John Miller wrote a very informative piece last fall, published on the Energy Collective, that examines the impact of unilaterally ceasing all fracking operations in this country.

Given that domestic shale gas production has increased tenfold since 2006, the U.S. is projected to provide 9 percent of worldwide supply by 2040. We have, in fact, been transitioning from a natural gas importer to a natural gas exporter. Most imports have come from Russia and the Middle East. They are currently projected to fall to zero by 2020, but that trend would clearly reverse without fracking. In a nutshell, this would cause substantial economic disruption both at home and around the world at a time when most economies are far from robust.

That leads to the question I asked a couple of weeks ago: If we can’t make fracking unnecessary, can we at least make it safer? In that article I describe a number “green fracking” developments, some of which I originally mentioned here. One approach that sounds particularly promising is the use of propane gel to produce waterless fracking. The process uses a pressurized gel instead of water, which expands into a gas once injected that can be cleanly collected along with the liberated natural gas.

Since then, I have become aware of another effort by Solazyme to develop a green drilling fluid from algae. I have previously written about Solazyme and their efforts to develop biofuels from algae, notably for the aviation industry.

However, as producers of cellulosic ethanol have found, the road from R&D to full production is both long and challenging. Solazyme has cleverly branched into other markets--producing high-value oils for cosmetics, food additives and other chemicals, in smaller quantities--to keep the cash coming in as they continue to grow into a large-scale fuel producer. Earlier this month, Unilever announced a trial of Lux bar soap made using algal oil produced by Solazyme.

Solazyme's latest announcement brings the versatile the company into the oilfield services market. It features Encapso, a highly effective, encapsulated lubricant that is far cleaner than its predecessors and can also be used to enhance drilling performance and production rates. By using the entire algal cell, the oil contained within is encapsulated. That means the oil will not flow until the cell bursts during the actual drilling process. That allows for more targeted application of the oils and reduces oil seepage. Since shale oil and gas wells tend to be short-lived, that means there will be lots of drilling.

At the end of the day, exploitation of shale gas and oil fields seems to be the economic reality of the day--and fracking a necessary evil, if you will. Indeed, there have been many necessary evils along our path of development, many of which have gone unreported. In today’s world there is far more awareness and more transparency, which means that these activities and their risks are now in the public eye. Pressure will continue to be applied to undertake these as cleanly as possible, and, at the same time, to keep looking for cleaner and safer alternatives.

Image credit: Andrea: Flickr Creative Commons

RP Siegel, PE, is an inventor, consultant and author. He writes for numerous publications including Justmeans, ThomasNet, Huffington Post, and Energy Viewpoints. He and Roger Saillant co-wrote the eco-thriller Vapor Trails, the first in a series covering the human side of various sustainability issues including energy, food, and water in an exciting and entertaining romp that is currently being adapted for the big screen. Now available on Kindle.

Follow RP Siegel on Twitter.

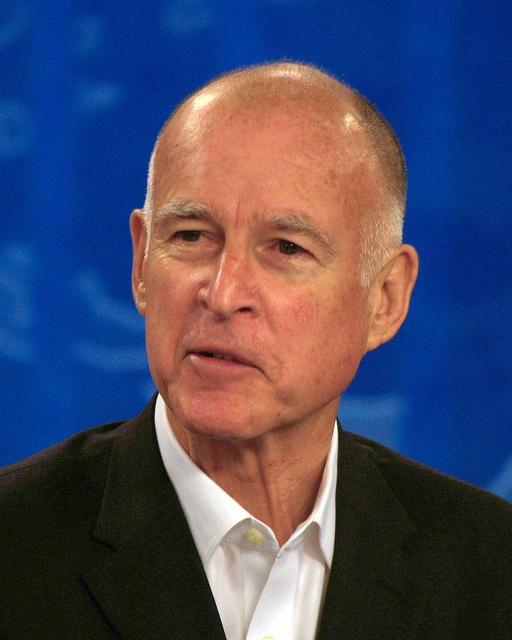

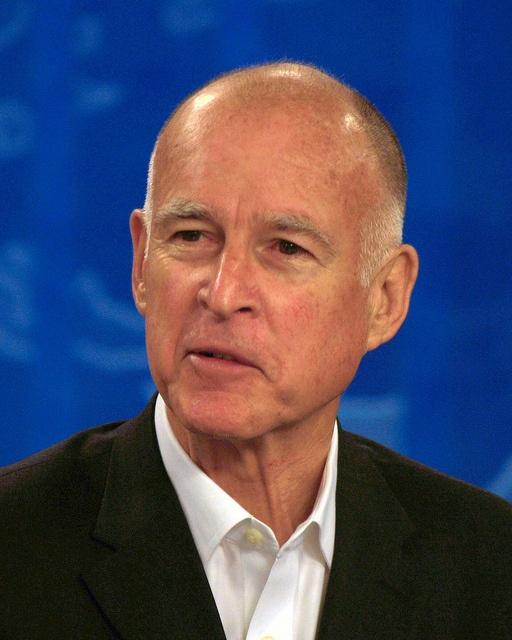

Gov. Jerry Brown: California is the 'Epicenter' of Climate Change

On Monday, Gov. Jerry Brown called California the “epicenter of climate change” while speaking at the University of California's Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics. Gov. Brown just might be right. This past week, wildfires have blazed across thousands of acres in Southern California. All of California is in a drought, according to the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor report. The U.S. Drought Monitor characterized 100 percent of the state as being in either a “severe drought or worse” and called attention to the heat wave “settling in, which will only serve to exacerbate and accelerate drought impact concerns across the state.” The Monitor also warned that there will be increases on water demand and increased fire risk as the temperatures rise.

Gov. Brown also appeared on ABC’s "This Week" discussing the impacts of climate change on California. “The state's climate appears to be changing,” Brown said. “The scientists tell us that definitely. So we've got to gear up here.” Brown made it clear that California is not just adapting to climate change but “taking steps to reduce our greenhouse gases in a way that I think exceeds any other state in the country.”

What is California doing to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs)? For starters, in 2005, then Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger signed an executive order setting short and long term greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals: to reduce GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020 and by 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. Schwarzenegger then signed the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 which set the reduction goals into law. In 2009, California adopted a Climate Adaptation Strategy, which summarizes climate change impacts and recommends adaptation strategies.

California is encouraging the growth of renewable energy. The state has one of the most ambitious renewables portfolio standards (RPS) in the country. Established in 2002, it was increased in 2006 and expanded in 2011. It requires utilities to obtain 33 percent of total electricity from renewables by 2020. California also is putting a price on GHG emissions: In early 2012, California’s Cap-and-Trade Program took effect, and on Jan. 1, 2013 the enforceable compliance obligation for GHG emissions began. California is part of the Western Climate Initiative, a collaboration of several western states and Canadian provinces to create a regional carbon trading market.

California takes energy efficiency so seriously that it is using the grizzly bear on its state flag to promote the importance of using power more efficiently. For two weeks this month, the bear is “traveling” around the state promoting energy efficiency. Energy Upgrade California launched a contest via social media so California residents can locate “Where the Bear” is--promoting energy efficiency in the state.

Image credit: Phil Konstantin

Op-Ed: The Hidden Costs of 'Cheater Economics' on Human Health

Ed Note: A version of this post was originally published on The Daly News.

By Brent Blackwelder

In a true cost steady state economy, the real costs of goods and services would not be disguised, hidden or kept off the accounting ledger. The former head of Friends of the Earth England, Tony Juniper, makes a significant contribution to the discussion of a true cost economy in his new book "What Has Nature Ever Done For US?: How Money Really Does Grow on Trees."

'Cheater economics' enables polluting products to be sold cheaper than many clean products and includes subsidies for fossil fuels, pesticides and toxic chemicals. Cheater economics tolerates pollution externalities, as economists have noted. For example, many damages caused by air pollution from coal-fired power plants are not incorporated into the price of coal but simply borne by the victims. The act of mountain top mining eliminates forests and streams while air pollution from burning coal results in loss of crops, damage to buildings, health problems, and mercury contamination of fisheries, etc.

Here is a sample of the astonishing set of ecological costs stemming from economic activities that damage or rearrange ecosystems that are presented in "What Has Nature Ever Done For US?"

Vultures in India

India has almost lost its total population of 40 million vultures as a result of anti-inflammatory drugs injected into cattle and water buffalo. The vultures consumed the carcasses of these and other dead creatures and accumulated a fatal dosage. Now 12 million tonnes of animal flesh that vultures consumed annually is left rotting, fed upon by growing packs of dogs that have caused a massive outbreak of rabies among the human population. The annual medical costs exceed $30 billion as a result of the demise of the vulture population, which had previously provided free of charge essential garbage/carrion collection services.Pollinators of human food crops

About two thirds of the world’s food crops require animal pollination and one trillion dollars of the $3 trillion annual sales of agricultural products are dependent on animal pollinators such as honey bees and bumblebees. Certain pesticides are killing off these crucial pollinators. In the 1980s, extensive use of pesticides in part of Sichuan, China, eliminated the bee pollinators. Today in this region, about 40,000 people now have to pollinate apple and pear trees by hand.

The United Nations Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports that in 146 countries, 90 percent of the food supply is provided by 100 crops. What is significant is that 71 of these 100 crops are pollinated primarily by wild bees. These crops include squashes, cherries, plums, cucumbers, strawberries and pears.

Destruction of ocean fisheries via subsidies

Ocean fisheries contribute $274 billion for global GDP but various countries provide $16 billion in subsidizing fishery harvesting practices that are highly damaging to fish stocks: i.e., the equivalent of killing the goose that laid the golden egg.

One square kilometer of mangrove forest is worth between $200,000 and $900,000 annually. Destruction of coastal mangrove forests, as occurs with Asian shrimp farms, eliminates the storm protection barrier that is increasingly important in the face of sea level rise.

High health care costs as a result of destroying natural areas

To deal with the poor health of people in the polluted Gateshead area in Northeast England, a group of British public agencies in 2004 initiated a program of walks in a 360 hectare mixed forest zone. Tony Juniper reports that these walks were very effective in improving patients’ health and were far superior to the alternative of exercise in a gymnasium.

A growing body of evidence points to the health benefits from interactions with nature. Dr. William Bird, a British doctor, ran a diabetic clinic in the 1990s in Oxfordshire where he initiated a very successful program of health walks in natural areas. But the sad fact is that natural areas are declining in many urban areas. In Sheffield, England, the “roaming” range for children has declined over 5 generations from six miles when the great-grandparents were children to about 300 yards today for children. The health costs of destroying natural areas globally is simply a pollution externality for developers and extractors and is shoved off on the public.

Pharmaceuticals and the loss of tropical rainforests

Experts estimate that between a quarter and a half of the $640 billion global pharmaceutical market is based on natural genetic diversity. Tropical rainforests contain a significant portion of the genetic diversity on earth, but despite the grave concerns about deforestation, an area the size of Germany or Montana was lost between 2000 and 2013.

To establish a true cost economy, we must get the ecological price right on products and services. The examples presented in Juniper’s book illustrate the extraordinarily large benefits provided by nature but neglected in today’s economic accounting. These compelling illustrations can be of great benefit in pushing toward a paradigm shift in current mainstream economic thinking. They are straightforward matter-of-fact descriptions of externalities that are undermining the life-support ecosystems of the Earth.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) should be requiring companies to disclose their pollution externalities annually so as to alert investors and the public to the true cost of their products. However, not only will a steady state economy depend on accounting for these costs and putting an end to cheater economics, but will also depend on changing our macroeconomic policy goal of continuous growth. Only then can we begin to stop the destruction of our planet and ensure our health and the environment are protected for generations to come.

Image credit: Nagarjun Kandukuru

Sociocracy: An Organizational Structure for Distributed Leadership

Many organizations are governed by top-down or command and control management. This management approach is based on the notion that the boss has all the answers and that the employees will be slackers if not kept in line (also known as Theory X by psychologist Douglas McGregor). By contrast, Theory Y depicts employees as intrinsically motivated with a participatory approach to problem-solving.

Although the latter may sound like a good idea--helping to bring out the best in employees--it is difficult to implement on a factory floor or in an office setting. It requires a cultural shift that isn't prevalent in schools, government and organizations. Sociocracy, or Dynamic Governance, is an organizational structure developed by Gerard Endenburg, a Quaker born in the Netherlands who was the CEO of Endenburg Elektrotechniek during a downturn. Sociocracy provides a non-authoritarian organizational structure that empowers people to make decisions within their domains, and fosters trust and effective decision-making.

Sociocracy organizes participants in circles, has feedback loops and uses consent (not consensus) decision-making. Circles elect delegates to represent their circle as a member of a higher circle. The top circle in a corporation would include the CEO, the board, and at least two members from the general management circle, with all members participating fully in decision-making. The organizational structure assumes that all participants have a piece of the "answer" or a special contribution, thus encouraging all voices to be heard.

Consent

Many hierarchical organizations have a decision-making body that creates policy and relies on other employees below them to enforce that policy, regardless of buy-in. In sociocracy, consent is reached when there are no "paramount objections" to a proposal, which occurs when it conflicts with the organizations aims or mission.

"Everything is done with an aim," explains Jerry Koch-Gonzalez, while leading a sociocracy workshop for Belfast Ecovillage. "The greater the divergence of the group [regarding the aim], the harder it is to work together."

Circles

These semi-autonomous entities use consent decision-making within a given domain and are given freedom within defined parameters. Individuals make decision in matters that directly affect their work and leadership is distributed. The group determines by election which individuals have specific roles or functions, such as delegates or facilitators, and for what length of time. The circles aren't isolated bodies, but rather two members of a circle participate in the higher circle (double linking) and the circles are linked in a non-hierarchical manner. There guiding principles provide the structure for sociocracy, but transparency is the necessary ingredient.

Feedback loops

Policies are in effect for a specific period of time and will be evaluated at or before the given time period ends. The policy can then be ended, revised or continued, depending on the feedback. This practice allows of reflection and continuous improvement over time.

Transparency

All members of the organization need access to information--such as meeting agendas, minutes and organizational policy--for sociocracy to thrive. The exceptions to this would be proprietary knowledge or information that presents a security threat to individuals or clients. All members of circles must feel empowered to raise concerns, for sociocracy to function. A tool in achieving this is rounds at a meeting, where all participants have the opportunity to speak about a proposal, asking clarifying questions, giving quick reactions or suggesting amendments to a proposal.

"All these things support everyone having a voice," explains Gonzalez. " Nobody can be ignored. Feedback loops allow people to keep learning."

Beyond the walls of a single corporation, sociocracy can be applied to link various stakeholders. For example, small farmers can gather to form a cooperative business to negotiate contracts with retailers or shipping rates with transportation companies. Woodbury University utilizes sociocracy to foster trust and collaboration between departments. Nonprofit organizations are using sociocracy to boost participation and incubate innovative ideas and Mondriaan, a large mental health facility in the Netherlands is using it to create distributed leadership. Cohousing communities, including Belfast Ecovillage and Pioneer Valley are attempting to reduce the time spent in meetings for all members by delegating tasks to small groups.

Image credit: Flickr/Baltic Development Forum

Sarah Lozanova is a regular contributor to environmental and energy publications and websites, including Mother Earth Living, Green Building & Design, Triple Pundit, Urban Farm, and Solar Today. Her experience includes work with small-scale solar energy installations and utility-scale wind farms. She earned an MBA in sustainable management from the Presidio Graduate School and she resides in Belfast Ecovillage in Midcoast Maine with her husband and two children.

Op-Ed: Latest Global Roundtable on Sustainable Beef Criteria 'Falls Short'

Ed Note: A version of this post originally appeared on the Natural Resources Defense Council's Switchboard blog.

By Jonathan Gelbard

This past Friday, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and our partners at Rainforest Alliance, Food Alliance and Friends of the Earth U.S. submitted joint comments to the Global Roundtable on Sustainable Beef (GRSB) detailing why the latest version of its “Principles” and “Criteria” falls short of serving as a credible framework for recognizing sources of verified sustainable beef.

We offered recommendations on how the GRSB can better translate the “menu” of proven ranch and farm management solutions into effective yet practical criteria for recognizing credibly less impactful sources of beef. That is, those that can be trusted to come from ranches, farms, feedlots and feed crop operations that maintain the health of ecosystems and their biodiversity, prevent and minimize pollution, and protect public health, animal welfare and the well-being of farm workers.

Climate change

GRSB’s criterion for minimizing the massive carbon footprint of beef production ignores strategies for reducing methane emissions (now estimated to have 34 times the global warming potential of CO2). After all, burps and farts of cattle and other ruminants (enteric fermentation) are the single largest source of methane emissions in the U.S. (24.9% of the total according to the EPA’s 2014 greenhouse gas inventory). Manure management is fifth (9.4%). GRSB also fails to mention opportunities to reduce nitrous oxide (310 times the global warming potential of CO2) from feed crop production and manure management.

Land conversion

We applaud the GRSB’s acceptance that deforestation from cattle expansion must be “minimized and eventually eliminated”. Yet it seems easy for producers to say they are in compliance because they will “eventually” stop cutting forests to create pasture. Why not set a target date for eliminating land conversion driven by cattle expansion, such as within five years?

Deforestation is, of course, not the only type of land conversion associated with beef production. Here in the U.S., 23.6 million acres of grasslands, wetlands and shrublands were converted to row crops (particularly corn—much of that ending up as feed for farm animals)—between 2008 and 2011 alone. This conversion is destroying our precious grassland heritage and releasing large amounts of carbon from the soil (where it is beneficial) into the atmosphere (where it accelerates climate change). For this reason, we believe this criterion should encompass all types of land conversion related to beef production.

Freshwater conservation

The GRSB falls short on fresh water conservation in several ways:

- What about groundwater? Numerous scientific studies have found that poor manure management can cause both surface and groundwater pollution, including of expensive-to-replace drinking water supplies.

- Water quality AND quantity. The criterion does not address fresh water depletion in water scarce regions. We recommended an additional criterion to cover water quantity.

- Toxic pollution in our waterways. The Fresh Water criterion does not address impacts of toxic pollutants from feedlots or processing facilities, where residues of antibiotics, hormones, heavy metals, pesticides, and pathogens in manure, not to mention dead-zone forming nutrient pollutants, are too often discharged into waterways.

Soil health and high conservation value habitats

Healthy soils are the foundation of healthy ranches and farms. They support forage plant growth, absorb and store water, and help counteract climate change by trapping carbon below ground. Thus when well-cared for, healthy soils buffer ranches and farms against the impacts of drought and climate change, and enable them to recover more quickly once rainfall returns. Given the foundational importance of soil quality, we are curious why GRSB lumped it into a criterion with high conservation value habitats (i.e, lands important for conserving rare, threatened and endangered species and habitats – whose conservation is also an essential part of responsible ranching). We recommended that both receive their own criterion.

Additionally, we advised replacing the vague language pertaining to soil health (simply requiring “adoption of appropriate management practices”) with something more specific and outcome-based: Beef production systems maintain or improve soil quality by minimizing erosion, maintaining or enhancing soil carbon and nutrients at appropriate levels, and promoting healthy biological systems and chemical and physical properties.

Feed crop production

GRSB’s current criterion simply requires that “Where possible, feed is sourced from verified sustainable sources.” It seems easy for beef producers to claim they meet this requirement because it is not “possible” to source feed from verified sustainable sources. It is also important to define outcomes of what “sustainable feed” really means. Using fewer chemical inputs, protecting and restoring soil health, preventing conversion of diverse forests and grasslands to monoculture crop fields, protecting pollinators and predators of pests, and reducing runoff that pollutes our waterways are all critical elements of more sustainable feed crop production systems.

Responsible manure management

GRSB currently lacks criteria for defining responsible manure management. A single cow can produce as much excrement as 20 people, so beef feedlots can generate as much raw sewage as an entire city. As such, this suite of criteria will remain incomplete until it includes a definition of responsiblemanure storage – that which prevents leakage into streams and groundwater, protects against catastrophic failure of manure storage and runoff catchment lagoons, and fortifies manure storage facilities against 100+ year extreme precipitation events. This criterion should also define outcomes pertaining to responsible manure disposal – e.g., that manure is applied to crop fields at appropriate agronomic rates, as required to prevent the excess from running off into waterways and contaminating drinking water.

Use of pharmaceuticals to maintain animal health and welfare

We are deeply concerned that current language, which calls for “preventative” health care to “control” disease, could be interpreted to enable routine, non-therapeutic uses of antibiotics. A growing body of science has documented that such misuses of antibiotics (including for disease prevention and growth promotion) degrade the effectiveness of critical human medicines, and contribute to the breeding of antibiotic-resistant superbugs that threaten human health. GRSB should require that antibiotics be used only to treat sick animals, and never for routine disease prevention.

Other areas in which we identified important weaknesses include criteria related to air quality; biodiversity; climate change adaptation; use of other pharmaceuticals, nutrients and chemicals; and use of technologies to improve efficiency.

Toward credibly more sustainable (or at least “better”) beef

We acknowledge the difficulty of crafting Principles and Criteria suitable for widely diverse groups of stakeholders, especially at the global scale given the vast diversity of beef production systems, regionally-relevant impacts, and locally appropriate management solutions. However, the GRSB’s latest draft contains critical flaws that render it vastly inadequate to serve as a credible framework for recognizing verified sustainable beef in the marketplace.

NRDC and our partners look forward to working with the GRSB and its members on not just improving these Principles and Criteria for defining more sustainable beef, but also on implementing guidelines for more sustainable cattle ranching and farming, including via regional roundtables.

Image credit: Flickr/intercontinentalhongkong

Jonathan Gelbard is a conservation scientist and sustainable agriculture specialist based in San Francisco. Read more from Jonathan on the NRDC Switchboard blog.

Homeworking could save 3bn tonnes of carbon a year

Increasing the numbers of UK employees working from home could save over 3 million tonnes of carbon a year as well as cut costs by £3 billion a year for UK employers and employees, according to a new report by the Carbon Trust.

While over 40 per cent of UK jobs are compatible with working from home, the Carbon Trust found that only 35 per cent of companies have a policy allowing their employees to work from home. And where homeworking is offered by companies, between one-third and one-half choose not to accept it.

Homeworking reduces employee commuting, resulting in carbon, money and time savings. If office space is properly rationalised to reflect this, homeworking can also significantly reduce office energy consumption and rental costs.

However, the research revealed a critical finding: carbon savings are sometimes not achieved because of potential rebound effects, particularly the increased carbon emissions from employees now working in homes that are often energy inefficient. Business must therefore take care to factor in their individual circumstances when considering homeworking policies, to ensure that these will actually cut carbon emissions and not increase them.

Hugh Jones, Managing Director of Advisory at the Carbon Trust, said: “Homeworking is on the rise, with numbers increasing by over half a million since 2007. This new research shows that in the right circumstances, it has the potential to be expanded significantly and be a win-win for business and the environment.

“Significant financial and carbon savings can be achieved from the roll out of homeworking. But companies must be careful to ensure that they get the balance right, for if employers do not take account of their individual circumstances, a rebound effect, from employees heating inefficient homes, may actually lead to an increase in carbon emissions.”

Picture credit: © Ala Charnyshova | Dreamstime.com

OECD urges action to reduce road traffic pollution

Air pollution is costing advanced economies plus China and India an estimated $3.5 trillion a year in premature deaths and ill health and the costs will rise without government action to limit vehicle emissions, a new OECD report says.

In OECD countries, around half the cost is from road transport, with diesel vehicles producing the most harmful emissions. Traffic exhaust is a growing threat in fast-expanding cities in China and India, as the steady increase in the number of cars and trucks on the road undermines efforts to curb vehicle emissions.

“The price we pay to drive doesn’t reflect the impact of driving on the environment and on people’s health. Tackling air pollution requires collective action,” said OECD secretary-general Angel Gurría, presenting the report at the International Transport Forum’s 2014 Summit in Leipzig, Germany.

The Cost of Air Pollution: Health Impacts of Road Transport calculates the cost to society across the OECD’s 34 members at about $1.7 trillion, based on the value people attach to not having their lives cut short by cancer, heart disease or respiratory problems. It puts the cost at nearly $1.4 trillion in China and nearly $0.5 trillion in India.

More than 3.5m people die each year from outdoor air pollution, says the OECD. From 2005 to 2010, the death rate rose by 4% worldwide, by 5% in China and by 12% in India.

The report underlines the fact that there is no public policy case for applying preferential tax treatment to diesel. It also supports taking action to reduce road transport pollution which could include tightening emission standards, expanding urban bicycle-sharing and electric car programmes and extending road charge schemes to reduce congestion.

“There is no environmental justification for taxing diesel less than petrol. Air pollution is destroying our health and the planet. Phasing out tax incentives on diesel would be a step towards reducing the costs to both and in fighting climate change,” said Gurría.

Picture credit: © Ilya Glovatskiy | Dreamstime.com

It IS About Logistics: How FedEx Integrates Community Engagement into its Core Operations

Submitted by Guest Contributor

By Jackie Norris, Executive Director, and Yvonne Siu Turner, Senior Manager, Corporate Resources and Programs, Points of Light Corporate Institute

This is part five in a seven-part blog series exploring the community engagement practices of winning companies in The Civic 50, an initiative launched in 2012 by Points of Light, the National Conference on Citizenship and Bloomberg. The Civic 50 identifies the top 50 community-minded S&P 500 corporations that best use their time, talent and resources to improve the quality of life in the communities where they do business.

Today, we explore how FedEx has integrated volunteering and community engagement into its core business strategy and specifically how it helps communities in times of disaster.

When Hurricane Sandy pulverized parts of the East Coast in 2012, Bill Bonneau found himself in a unique position. As manager of station operations for FedEx Express, he could help deliver relief supplies throughout New York.

“FedEx’s logistical expertise and  extensive network made us a key player,” said Bonneau. “Despite the logistical challenges associated with route access after a natural disaster, we found a way to answer the call.”

extensive network made us a key player,” said Bonneau. “Despite the logistical challenges associated with route access after a natural disaster, we found a way to answer the call.”

Together with thousands of FedEx volunteers, Bonneau directed an effort to deliver almost four million pounds of relief aid for agencies such as the American Red Cross, Heart to Heart International, Direct Relief and The Salvation Army. They delivered everything from meals and clothing to water and medical supplies. They provided logistical expertise to deliver more than 85 generators to LaGuardia Airport, police stations and even polling stations to help residents vote during the 2012 presidential elections.

Thanks to volunteers like Bonneau, agencies like Direct Relief quickly met community needs. “The residents of the area were really hit hard after Hurricane Sandy,” said Kerri Murray, vice president of communications for Direct Relief. “Thousands lost power, heat, hot water, so we distributed personal care packs, nutritional supplements and food supplies, all delivered by FedEx.”

In total, FedEx provided $1.5 million in monetary aid, moved nearly four million pounds of disaster aid supplies and shipped 23,000 meals and 17 polling stations in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy.

For Bonneau and his colleagues, volunteerism is part of the FedEx culture. The company has managed to connect the dots between corporate citizenship and employee satisfaction, skill development and strengthening the FedEx brand by integrating community engagement into its business – earning it the No. 1 spot in the “Business Integration” category of the Civic 50.

Here are a few examples of how this integration works at FedEx:

Volunteering During FedEx Cares Week Boosts Employee Loyalty and Satisfaction

From building solar-powered playhouses in the San Francisco Bay Area to helping prepare meals in Atlanta, almost 10,000 FedEx volunteers around the globe stepped up to contribute more than 46,000 hours during the company’s annual week of service in 2013.

What did they like about FedEx Cares Week? Reasons ranged from pride from  working for a company that gives back to meeting other FedEx employees with the same passion to support the community.

working for a company that gives back to meeting other FedEx employees with the same passion to support the community.

“During FedEx Cares Week, I had the opportunity to help make a difference in the lives of others. I felt proud to see the team spirit from all the team members who attended,” said Giulia Fontana, a FedEx volunteer.

Training Future Leaders through International Corporate Volunteerism

FedEx also launched a Global Leadership Program that began in 2012, which has included a total of 24 participants to strengthen the leadership skills of high performers. Groups of volunteers are sent in teams to emerging markets like Brazil and India to work with governments and NGOs on skills-based volunteer projects.

Returning volunteers report acquiring critical leadership skills such as recognizing cultural differences; encouraging teamwork; demonstrating resilience, flexibility, resourcefulness and creativity; mentoring; communication, and even conducting research.

“Outstanding program – learning to manage in a different culture displays your effectiveness in communication and lets you know your strengths and weaknesses,” said Paul Davis, Global Leadership FedEx Participant.

From the U.S. Chamber to NASCAR: Building a Good Corporate Citizen

Building on its disaster relief support, FedEx sponsored a month-long campaign in 2012 to help the American Red Cross promote its Ready Rating program, which helps small businesses prepare for disasters.

While the company could have written a check and walked away, FedEx chose to engage by using its wide array of relationships and corporate assets to support Ready Rating. The result?

NASCAR team owner Joe Gibbs and driver Denny Hamlin spoke on a satellite media tour to promote disaster readiness; America’s Small Business Summit featured a panel discussion addressing the need for small business preparedness with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Red Cross and FedEx; and a Red Cross Ready Rating ad ran in Inc. magazine featuring FedEx as a Ready Rating sponsor.

The campaign gave FedEx an incredible boost to its corporate brand: 32 small businesses signed up for Ready Rating and the ad reached over 700,000 print subscribers and nearly one million unique visitors online. As part of the satellite media tour, Hamlin also gave three national broadcast TV interviews and three local television interviews about the program, which generated more than 50 news stories reaching potentially more than 20 million people.

Raj Subramaniam, EVP for Marketing and Communications at FedEx summed it up: “FedEx built a commitment to CSR into the business from the very beginning—dedicating itself not just to moving packages but also to connecting people and businesses to the global marketplace, improving living standards and building social capital across the world. It’s credibility you can’t generate by simply making a donation, rather it needs to radiate from the heart of your company and your employees to believe in it.”

Why it's Important to Know Who Made Your Clothes (and What They're Made From)

By David Dietz, Modavanti

Fast fashion has become the hundred-billion dollar industry it is today on a very simple premise: As consumers, on face value, we will always chose the similarly styled $10 T-shirt over the $25 T-shirt. We'd be stupid not to if that were the whole story. But that simple premise, one that H&M, Zara and others have so expertly milked, doesn't tell the whole story. It's unfortunately not that cut and dry.

If that $10 shirt had a label saying it would only last three or four washes compared to the $25 shirt that would last a year plus, would that savings still be as appealing? Probably less so since you'd need to buy another dozen shirts to last you the year. Then what if you learned that that $10 T-shirt used dozens of more cancer causing pesticides than its $25 counterpart? Uh oh... Finally on top of it all, a sign above the rack read: "Your $10 shirt was made by garment workers toiling in slave like conditions so you pocket those 'savings.'" Yikes.

You’ll never find a $10 T-shirt on Modavanti, the sustainable fashion startup I founded. You’ll find a lot of cool brands with incredible stories, but if you are looking for a $10 tee or even a $20 shirt we’re not for you. And that’s something we’re damn proud of. In this modern era of fast fashion and a race to the bottom, we’re never going to compete on that price level, and we don’t want to, because that $10 tee you’re looking for was made by seamstresses working in slave labor conditions. Mostly women and girls as young as 12 with no rights or voice at all -- women and girls who make $38 a month so that we can save a few dollars on a T-shirt.

That’s the horrible reality about most of the clothing we wear. In 1950, more than 90 percent of our clothes Americans made were produced here at home. Today only 2 percent of all textile manufacturing worldwide is done in the U.S. Yet as consumers we hardly notice -- until something tragic happens. Like what happened a year ago, when 1,133 people were killed and over 2,500 were injured when the Rana Plaza factory complex collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

There were obvious warning signs about the building’s structural integrity which were ignored by local managers under pressure from major big-box retailers to meet quotas and satisfy a western crave for inexpensive, disposable clothing. But Rana Plaza wasn’t the first tragic incident and won’t be the last. Last year, the Bangladeshi garment industry produced roughly $23 billion in exports to the West, and yet according to Oxfam International, the 4 million mostly women garment workers are forced to live on half of what Oxfam deems a living wage.

As we remember the victims of one of the fashion industry’s worst disasters, it is time to say enough is enough. It is time to come together to continue to raise our voices and demand change. It is time to stand up and say: "Yes, we know where are clothes were made; we know who made them; and we know what they were made of." True fashion is a force to be reckoned with. It is an art form, a craft; it is beauty in motion. And it will mean even more because we all can turn fashion into a force for good.

Social and environmental catastrophes in our fashion supply chains are still happening all around the world. But there are a lot of incredible brands that are making a difference -- brands that are using fashion as a force for good. Brands like Nakate which works with Ugandan women with HIV to create beautiful jewelry and reinvests much of their profits into helping the women earn more than a living wage to be able to afford necessary medicine. Brands like Popinjay, which employs women in Pakistan who face severe gender discrimination to give them a sense of hope and increased dignity. Brands like Indigenous. which has empowered thousands of artisans in Peru and helped elevate them from poverty.

These are the new faces and leaders in fashion. Brands that know the story of how their clothes are made and are proud of those stories. Brands that believe in a transparent and fair supply chain. Brands that are using fashion as a force for good. Fifteen years ago organic food was for hippies. Then we had a food revolution. Five years ago hummers and other gas-guzzlers dominated our roads, now were in the midst of an electric car revolution. Last year, over 1,000 garment workers needlessly lost their lives so we could have $10 T-shirts. It’s time for a fashion revolution.

Join the revolution and look good, feel good and do good in what you wear.

David Dietz is the founder and CEO of Modavanti, an online fashion destination for the new generation of socially conscious consumers.

Image credit: Pexels