Investing in Sustainable Fishing: A New Lease on Life for New England Communities

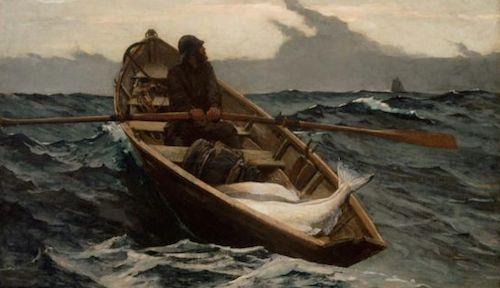

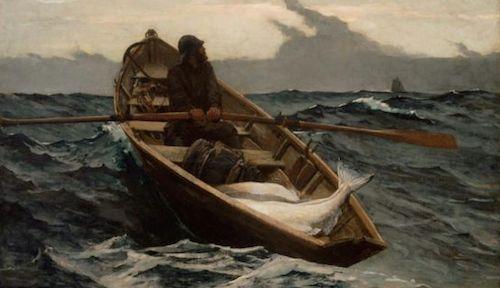

America was built on Cod.

When Americans today think of the first Thanksgiving feast, we often lean on our childhood history lesson version of events; the brave settlers celebrating with their new neighbors the survival of those first harsh months in a new world. Long tables of turkey and maize are etched in our minds, symbolizing a land of plenty and a unifying, if short-lived, bond with the newcomer’s native benefactors.

It is a foundational moment in the mythology that helped carve out a new country. But it was not as much the turkey and maize, but the even more bountiful harvest from the North Atlantic, cod especially, that underpins the foundation of the new American continent. Cod built colonial America, at least in New England.

It is said that cod was so abundant in those times that you could walk across the ocean on their backs.

Those days are long gone. The North Atlantic cod, once fabled as inexhaustible, is all but a faded memory of the past. What then happens to the towns and villages up and down the Atlantic seaboard that once thrived on what is now a tapped-out resource?

The communities that cod built

Many fear that a way of life for small-boat Atlantic fisherman is gone or nearly so; a fear endemic in many American communities like Cape Cod, where fishing has been the common organizing thread for centuries.

Fishing communities represent a resilient and traditional way of life. The evolving realities of growing competition for increasingly stressed resources challenges the survival of this resilinece. The fishing industry, including wild and farmed, represents a quickly changing, often controversial, and in most instances economically and emotionally disruptive future for the communities that cod built.

Resilience: A delicate balance of boom and bust

Periods of want and plenty were common in the North Atlantic. Historical research suggests that for at least 100 years the small fishing communities built up around groundfish (cod, flounder, halibut and sole) experienced cycles of “boom and bust.” Periods of abundance were interspersed about every 30 years with severe decline, even failure, of local cod fisheries.

Fishing grounds were exploited, but mostly inshore and limited by the available technology of the day, maintaining an overall sustainable balance. The cod always came back, and the cycle helped forge an idiosyncratic cultural resilience to cope and adapt.

Then came industrial, global fishing. Fishing schooners gave way to large, deep-water trawlers. By the mid-2oth century ships became ocean-going fish factories, able to scrape up cod (as well as tons of wasted bycatch) and process the catch while still at sea.

Even a 200-mile exclusion zone could not keep the decimation of the North Atlantic cod at bay. The Cod Wars between Iceland and Great Britain, the changing demographics of Newfoundland outport communities, increased competition between extraction methods, and friction with international players brought cod fishing to environmental, social and economic crisis.

The tentative balance maintained between fishing communities and the cod that supported them was broken.

Managing fisheries, maintaining communities

The inability to sustainably manage or assess the cod fishery throughout the North Atlantic not only decimated the fish -- once crowding the seas from North America to Northern Europe -- but also tore communities apart.

Despite nearly a century of warning signs that cod fisheries could not long withstand the onslaught of industrial fishing, the collapse in 1992 of the once great cod fishing grounds off the Grand Banks of Newfoundland caught Canadian communities, government and resource managers off-gaurd. Left without a means of supporting their families, as many as 30,000 small boat fisherman were left angry, bitter and without jobs.

The writing was on the wall for New England fisherman. Many who spent their lives on the sea felt their way of life going the way of the cod -- into commercial extinction.

Small-boat fisherman up and down the Atlantic coast grew ever more skeptical of quotas set by scientific fishery assessments. A pervading sense of uncertainty of whether the Cod would ever recover in New England, even if boat captains scrupulously maintain the quotas handed down, tested the resilience and optimism of even the hardiest of fisherman.

“The humans have been brought under control, but it’s still haywire,” Frank Mirachi, a Scituate, Massachusetts fisherman said in a 2013 Boston Globe article “I can’t get to a point of stability, because the system delivers endless chaos.”

Community development - fisherman helping fisherman

As fisheries management shifted toward Catch Shares or Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQ), sometimes referred to as "cap and trade for fish," small-boat fisherman in Cape Cod increasingly saw access to their own traditional fishing grounds snapped up by large global interests with the capital resources to trawl the seas with their floating fish factories, leaving little left over for anyone else.

But what the small fishing communities of New England lacked in sheer economic power was compensated by an economic force built on a bond community trust, of tradition and a determination to maintain a way of life -- independent, small boat fishing.

In 2005 a partnership, commercial fisherman in Cape Cod formed the Cape Cod Fisheries Trust. Through grants and low-cost loans, the trust can purchase Catch Share quotas and lease the Shares to local fisherman at half-market rates.

The trust manages the mechanics of leasing and transparency in pricing quotas through a key partnership with the Cape Cod Community Development Partnership.

A source I spoke with familiar with the trust emphasized the community-based approach and criteria required for access to the low-cost Catch Share quotas:

- The applicant must be a resident of Cape Cod

- An owner-operator of their boat

- Employ only local crew

For many, this approach has helped bring back a sense of optimism to the future of fishing off Cape Cod, but some still have reservations as to whether the trust can ever fully counterbalance the new reality of fishing in Cape Cod.

Despite an optimistic assessment for Gulf of Maine Cod in 2008, fisherman aren't seeing it in their nets. Quotas for cod haven't been filled in the region for a "number of years" says a source, and the optimism for cod professed in 2008 turned on its heels when the 2013 season was declared a "disaster."

What cod is left is pursued from large trawlers, based in bigger New England ports like Gloucester and New Bedford, able to venture further offshore -- though even then the cod is harder and harder to find.

But even if the halcyon days of cod fishing are done, access to community-driven solutions are vital to maintain a way of life through sustainable fishing. The small-boat, inshore fisherman of Cape Cod that once depended on groundfish began pursuing more plentiful species like starfish, moonfish, scallops and sea clams years ago.

The trust still holds Quotas for cod in order to leverage the power of local fisherman for the hopeful return of the cod, but most of the activity for leasing Quota Shares is for scallops and sea clams.

The sea clam is often considered the "poster child" for ITQ mismanagement. Sea clam was the first species in the U.S. to fall under an ICQ quota system in the late 90's, soon disappearing after large, vertically integrated commercial interests bought up the entire quota. What had been a traditional Cape Cod fishery was gone.

Fortunately, sea clams have now recovered, and the trust helps insure access to the sea clam fishery for local fisherman with a vested interest in its sustainable management.

A principal tenet of Cape Cod Fisheries Trust, beyond active on-the-ground support for Cape Cod fisherman, is to serve as a model for managing the nexus between evolving sustainable resource management and the survival of traditional fishing communities.

Market-based incentives and impact investing for sustainable fisheries

A March 2014 report from Oceana and RARE, entitled Sustainable Fisheries - Financing Strategies, explores how best to invest resources to sustain fisheries and fishing communities. Typically, the report states, fishery management and conservation has revolved around political advocacy, community engagement and media campaigns targeting “charismatic” species (North Atlantic cod, for instance) and threatened habitats.

Investment funds like the Cape Cod Fisheries Trust, the growing “traceable fish” movement and community engagement like the Gloucester Fisherman’s Wives Association are examples of market-based incentives increasingly employed, in one form or another, around the globe.

While each of these methods are effective if properly managed in the right circumstances, the report suggests these initiatives are further enhanced with impact investing to attract, as stated in the report's executive summary “private, return-seeking capital to support sustainable fisheries management.”

The report outlines three principal components of sustainable fisheries management that drive such investment:

- Commercial

- Regulatory

- Scientific

By unifying these three components, private investment can manage the complexities of fisheries restoration, price and supply chain volatility, and inadequate regulatory oversight.

The report identifies microfinance and SME (small to medium enterprise route-to-market), public/private partnerships and “Fisheries Impact” (providing investments directly for sustainable interventions) as three robust and effective investment models for sustainable fisheries management.

In the end, even impact or triple-bottom-line investing must be pragmatic. Effective vehicles such as those described here offer valuable return on investment while managing the inherent risk that has always been a part of fishing. Programs like the Cape Cod Fisheries Trust builds social cohesion and access to capital in communities beleaguered by endless quotas, declining fish populations and encroaching commercial interests.

In general, innovative strategies employed globally, yet addressing specific local needs, can accelerate the the impact of sustainable fisheries management.

Rooted in tradition, the story continues

The story of cod and small-boat fishing in America continues to evolve. But, until relatively recently, it has always been a story of resilience and abundance, of men and women taking to the sea and feeding a new world.

It is a romantic vision of the fiercely independent spirit that our mythology tells us built a nation. But too often that tradition of resilience and independence is overrun with globalization, industrialization, mismanagement and collapse -- of fisheries and fishing communities.

It doesn't have to be this way.

Through local community development, competent regulation and private impact investment, a new spirit of independence can emerge, built not on scraping the seas to desolation, but on flourishing communities put back in balance with the thriving fisheries the define them.

If we invest wisely, Cape Cod will always be a place to fish.

Image credit: "Rowing Home" by Winslow Homer, 1890

Finding a Narrative: 'Sustainability' Doesn’t Mean Anything Real to Consumers

Last week at the Sustainable Brands conference in San Diego, gDiapers CEO, Jason Graham-Nye said: “I think sustainability is like fight club. The first rule of fight club is don’t talk about fight club. The first rule of sustainability is the word is so dead.”

And he’s not alone. In one of the conference events, Raphael Bemporad -- co-founder and chief strategy officer at BBMG and Tensie Whelan, president of Rainforest Alliance -- presented a new report entitled The New Sustainably Narrative, which tries to address the following problem:

“Sustainability doesn’t mean anything real to consumers. Too often, it brings to mind technical issues or seemingly insurmountable environmental challenges.”

I guess this problem statement shouldn’t be surprising news to anyone involved in or following the many efforts to engage consumers in sustainability. The issue it raises has long become the Achilles' heel of the sustainability movement, making companies wonder what on earth can be done to get consumers on board.

So, what can be done to change the status quo when it comes to consumers with or without using the ‘S’ word?

Well, to answer this exact question a group of industry experts in consumer behavior met in a workshop hosted by the Rainforest Alliance. The group brainstormed “a new global narrative that taps into the consumer shift towards a broader and more meaningful set of values around mindful living and sustainability.” And the results of this effort can be found in The New Sustainably Narrative report, which was sponsored by Domtar and authored by BBMG.

The first part of the report includes some compelling information about consumer trends that was introduced by industry experts, including:

- Consumers don’t connect sustainability to their own wellbeing or success (BuzzBack Market Research)

- Consumers want brands to empower a meaningful life, and yet ... Most people would not care if 73 percent of brands disappeared (Havas)

- Brands must evolve to deliver on social and cultural benefits – caring for my wellbeing and the wellbeing of my family, for the wellbeing of my community and for the wellbeing of the planet (Coca-Cola).

When you look at these findings in the context of narrative then it becomes quite clear that the challenge is to translate sustainability into concepts people understand and find compelling -- wellbeing, betterment, purpose and so on.

Yet, it might be that the problem isn’t just the narrative but also the narrator. Many of the brands that struggle to make sustainability compelling to consumers are the ones that told us for many years stories in which their products are the heroes, helping us to express ourselves. Now as marketing expert Jonah Sachs explains companies interested in sustainability try to tell different stories, in which people, not the brands are the heroes.

In these stories brands empower helpless consumers to become true citizens that can make a difference. The only problem is that this transition isn’t easy because people apparently find it hard to believe that companies, which for decades were mostly focused on selling more stuff convincing us that “happiness is the smell of a new car,” suddenly take interest in our wellbeing, not to mention our communities’ wellbeing.

So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that all the examples brought up in the report on how to do it right when it comes to creating a sustainability narrative are of new companies (Lyft and Toms), B2B companies, or companies that worked from day one to build an authentic sustainable profile (Ben & Jerry’s and The Body Shop). Apparently rebuilding your sustainability narrative is much more difficult than creating it from scratch.

Still, this is not an impossible mission, and this is where the report comes in handy for companies facing this challenge. Its second part provides practical advice on how to engage people with an effective sustainable narrative. The first recommendation is to go tribal, exploring the symbols, language and rituals that shape our culture and approaching his tribe differently in accordance with these elements.

The report identifies three different tribes – the radius tribe: the people who do rather than talk (they share assets and skills, celebrate local traditions, and unite in local events); the good collective tribe: the people who make every moment count (they do good and volunteer, share their activities online and are rewarded for “do gooding” and sharing); and the bettering tribe: the people who see what’s possible (they enhance products, services and experiences to be more sustainable, influence companies by sharing ideas and experiences, and engage with them in various ways like crowdsourcing).

Okay, so we have divided the target market into three tribes. Now, what’s next? The report offers three simple but important key innovation pathways to reach these tribes: Communicate sustainability in the context of everyday life, connect to the universal aspiration to live a meaningful and happy life, and inspire innovation and refuse to accept compromise.

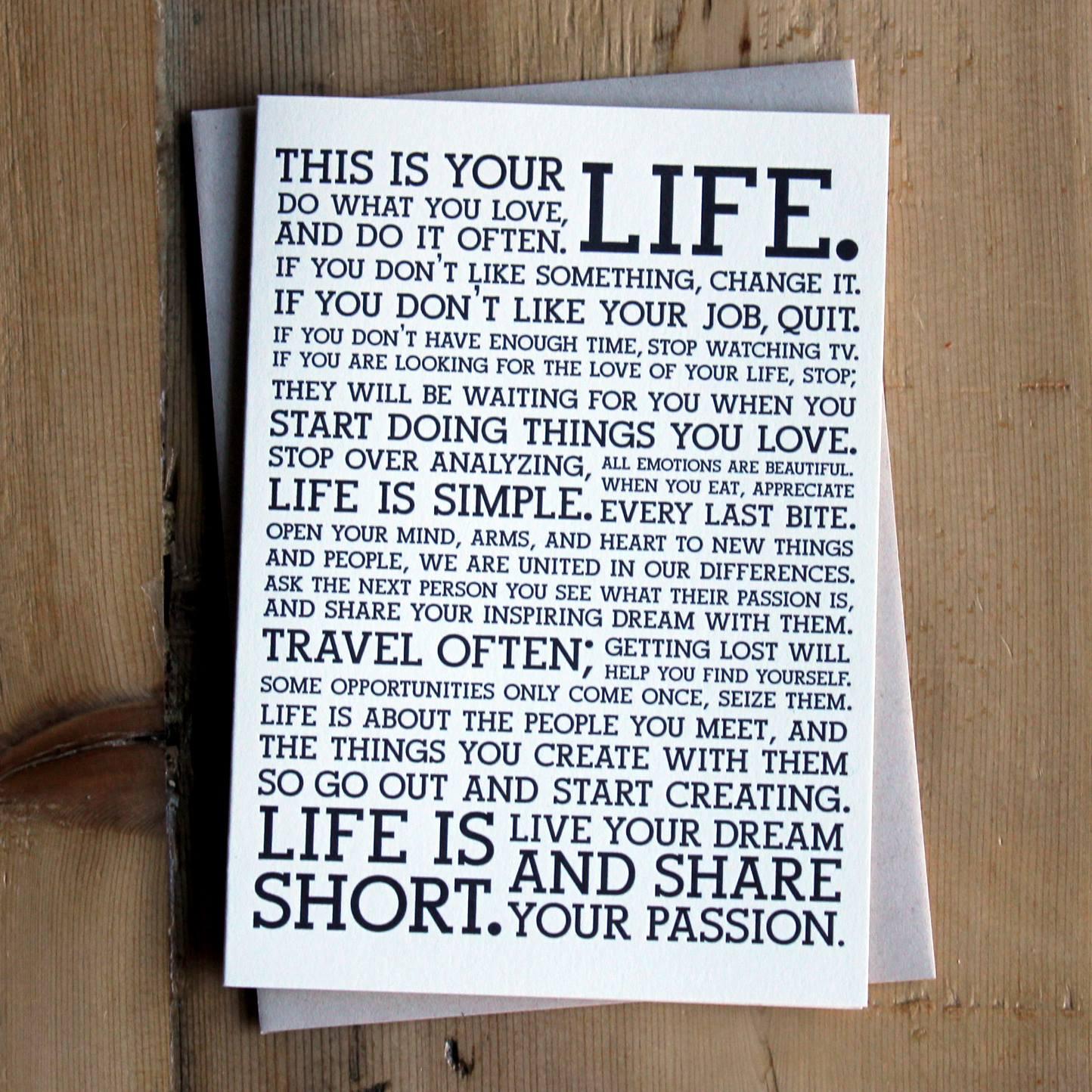

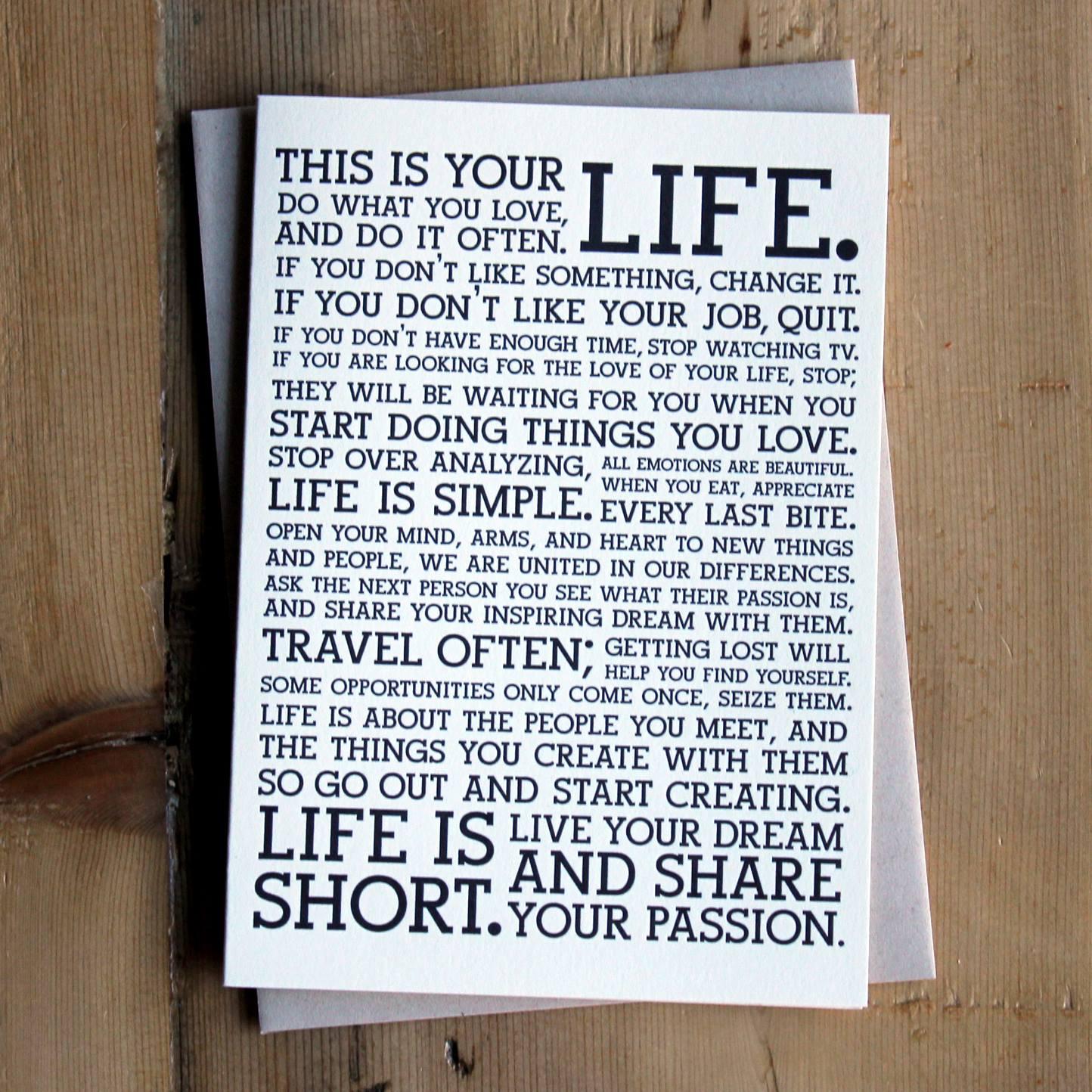

Finally, the report offers couple of takeaways on how might brands lead the way forward: give them something to believe in (for example Holstee manifesto); give them community to belong to (Toms); amplify their voices and creativity (GE garages); give them social status and something to share (Upworthy); and give them a platform for participation and impact (Ben and Jerry’s).

Overall, the report rightly identifies the disconnectedness between people and the sustainability as both a problem and an opportunity for companies. Can they meet this challenge? I believe the answer is yes, but only if they are really up to the challenge and understand that this is as much about the narrator (i.e. themselves) as it is about the narrative.

Companies should also remember that this fight is may be more about the seventh rule of fight club – “fights will go on as long as they have to” -- more than it is the first rule. The winners will be those that build an authentic, transparent narrative for the long run -- one that is all about sustainability, with or without the ‘S’ word in it.

Stay tuned for more coverage from the 2014 Sustainable Brands conference this week on Triple Pundit!

Image credit: Holstee

Raz Godelnik is an Assistant Professor of Strategic Design and Management at Parsons The New School of Design. You can follow Raz on Twitter.

Report: Government Could Catalyze Growth in U.S. 'Impact Economy'

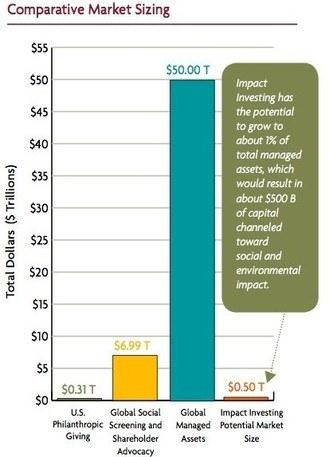

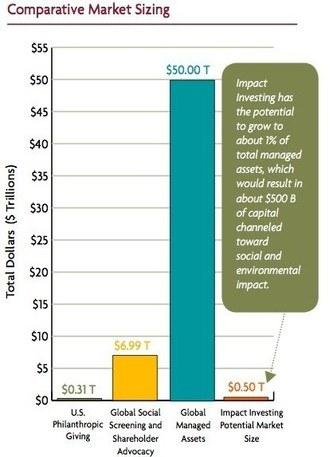

Employing as many as 10 million Americans and generating an estimated $500 billion in annual revenue, the U.S. “impact economy” is already sizable, and still developing. Growth could be accelerated substantially were the federal government to make a concerted effort to support the social enterprise sector's ongoing development, according to a policy paper from Deloitte Consulting's GovLab.

Emerging over the course of the past decade, the so-called “impact economy” has grown rapidly as entrepreneurs, investors and nonprofit sector leaders across the U.S. began developing more socially and environmentally conscious and responsible business models, legal structures and investment vehicles. Yielding triple bottom line returns, 2020 growth prospects for “impact investing” have been estimated to range between $400 billion and $1 trillion.

Part and parcel of a broad-based effort to spur further growth in the impact economy, federal government action to develop a market for “Payment for Success” (PFS) financial instruments, such as social impact bonds, would help make up shortfalls in government budgets and deliver substantial social and environmental, as well as economic, benefits across society, Deloitte GovLab asserts in, Government and the impact economy.

The Impact Economy's triple bottom line returns

In its report, Deloitte Consulting's GovLab zooms in on the social impact bond as an example of the “win-win-win” manner in which innovative “impact investing” can deliver triple bottom line benefits across society.

As GovLab recounts, the first social impact bond was launched in the U.K. in 2010 with the objective of reducing recidivism at Peterborough Prison. Since then, 16 social bonds have been issued in the U.K. and nine in the U.S. According to the report authors:

“These activities as well as other innovative financing mechanisms have contributed to an ecosystem in which a range of support organizations are eager to participate in the impact economy...With the rise of the impact economy, all have an opportunity to challenge conventional thinking and reinvent their models.”

The federal government's pivotal role

As is true for any new economic sector or market, the federal government can play a vital role in shaping and supporting the impact economy's growth and development.

In the report, Deloitte GovLab authors outline steps the U.S. government could take to help the social enterprise sector realize its full potential, broken out across three main lines:

- As a convener or “market facilitator,” by providing resources and infrastructure and building relationships among those engaged in building the impact economy;

- As a buyer of goods and services, by focusing more public resources on achieving social outcomes; and

- As a regulator, by crafting regulations, policies and incentives that drive more investment capital into the impact economy.

More specifically, in its prospective role as a market facilitator, Deloitte GovLab encourages the Obama administration and Congress to:

- Build a repository of leading practices;

- Develop platforms to facilitate investment;

- Standardize and track metrics; and

- Create dedicated impact funds.

As a buyer of goods and services, GovLab continues, the federal government could:

- Fund Pay for Success and other performance-based programs; and

- Reform procurement processes.

Finally, as a regulator, the federal government could catalyze development and growth of the impact economy by:

- Creating legal defnitions for social enterprises;

- Encouraging impact investment through the tax code;

- Reforming the Community Reinvestment Act; and

- Clarifying definitions under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act

An L3C – low profit, limited liability company – whose business is firmly rooted in triple bottom line principles, 3p is a growing part of the impact economy landscape. As such, it plays an active role, as well as having a growing stake, in its ongoing growth and development. As Deloitte GovLab highlights in the conclusion to its report:

“With promising new vehicles such as social enterprises, social impact bonds, impact investments, and benefit corporations, we have a chance to use public and private investment in ways that generate real, measurable social impact.

“If the impact economy is to reach – or top – $1 trillion by 2020, the federal government will need to encourage its growth and activity, set the rules of the road, and help bring together a diverse community of players.”

*Image credits: 1) IR Matters; 2) WhyDev; 3) SOCAP

Finland Aims for 80 Percent Emissions Cuts with New Climate Act

Not heavily industrialized and with large tracts of remaining forest, Finland contributes a small percentage of global greenhouse gas emissions. Yet, like many nations around the world, it is experiencing the effects of climate change to a disproportionate degree. Situated at Western Europe's northernmost extreme, climate change is making an impact on just about every aspect of Finnish life and society.

Nearly 500 national climate change laws have been passed in 66 countries, according to the 2014 GLOBE Climate Legislation Study. Adding to these numbers, Finland's government on June 6 approved a proposal for a National Climate Act that entails reducing carbon and greenhouse gas emissions 80 percent by 2050.

Finland's ambitious climate change action plans

A member of the European Union (EU), Finland has already pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions at least 20 percent by 2020. The northern European nation is also a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and Kyoto Protocol.

Passage of the national climate change act is seen as reinforcing and building momentum for these initiatives, as well as the nation's own Low Carbon Finland 2050 program and efforts to establish climate change mitigation and adaption as core aspects of its economic, social and environmental policy framework.

Finland's changing climate

2013 was an exceptionally warm year in Finland, with the country's central region experiencing higher than normal levels of precipitation, according to preliminary statistics from the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

Experiencing its sixth warmest year on record, the 2013 mean temperature across most of Finland was 1 to 2 degrees Celsius (1.8 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than the long-term, 1981-2010 average. The one exception was in the coastal southwest, where last year's deviation from the long-term average temperature remained just below 1 Celsius degree.

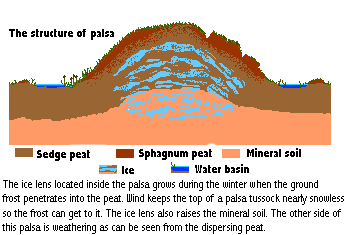

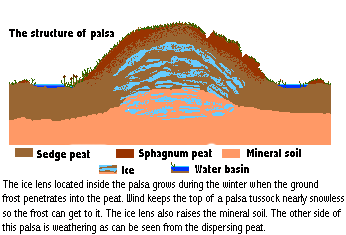

Extensive ares of palsa mires wetlands typical of Finland's Lapland region are beginning to disappear, and a shift in plant species composition, richness and frequency is occurring at altitudinal margins due to recent trends in temperature and precipitation, according to the U.N. International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report.

Expected continuation of such trends will bring costs and benefits. On the one hand, Finland will become more suitable for cultivation of crops grown primarily in southern Europe, such as maize, sunflower and soybeans. On the other hand, a continuation of the warming trend is likely see the melting of large areas of permafrost that may turn arctic regions for a net carbon sink to net source of carbon emissions.

Government plans for a low carbon Finland

Finland was the first nation in the world to complete a national climate change adaptation strategy. Published in 2005, Finland's national climate adaptation strategy “outlines adaptation measures for 15 sectors up to the year 2080 and considers both anticipatory measures and measures responding to the effects of climate change,” the Finnish Foreign Ministry explains.

Incorporating climate change mitigation as well as adaptation measures, the proposed national climate change act would set Finland firmly on a course to a low carbon society. Greenhouse gas emissions reductions of 80 percent by 2050 are envisioned.

A political breakthrough ushered in passage of the proposed new climate change act. Quoted in an Eco News post, Finnish Minister of Environment and Greens Party MP Ville Niinisto stated:

“The climate change act is an attempt to establish Finland as a leader in low-carbon society. The current emissions targets, which extend until 2020, are simply not enough, and we must plan for the society of 2050 today.”

Characteristic of climate change policy debates in the U.S. and around the world, concerns about the possibility that enacting strong greenhouse gas emissions reductions initiatives would hinder economic growth were paramount in the political deadlock in Finland. Proponents of taking stronger, longer term actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate and adapt to climate change eventually won out.

Countering such contentions, Energy Minister Niinsto stated, “In fact, this is an opportunity for Finnish industries. It’s a breakthrough that so many sectors seek to address these issues. We will commit to the emissions cuts cost-effectively in order to ensure that the economy thrives and the well-being of citizens increases.”

Image credits: 1) Yle Uutiset; 2) Finnish Meteorological Institute; 3) Oulu Finland; 4) VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland

Why Finance is (and Always has Been) an Important Sector for Impact Investors

By Marta Maretich

If you were asked to guess which sector attracted the biggest proportion of impact investment, which would you say it was? Looking at the websites of major impact intermediaries and financial institutions you might guess the answer was agriculture, clean energy, water, or healthcare. But you’d be wrong. Finance still makes up the biggest single slice of the impact investing pie. According to the recent survey by GIIN and JP Morgan, 42 percent of all impact investing assets under management in their sample were finance, with microfinance and financial services each accounting for 21 percent of the total. This compares to just 8 percent for agriculture, 11 percent for energy, 6 percent for healthcare and just 3 percent for water. This means that a significant proportion of impact investments are actually made into finance institutions, and not directly to companies or individuals.

This answer may surprise you — it may even disappoint you — but it shouldn’t.

The social investing movement has its origins in banking, with well-meaning pioneers trying to find ways to use the tools they understood — financial tools — to better the lot of their fellow men and women. Providing finance, whether in the form of small loans or more sophisticated services like consumer credit or banking, was the possibly earliest form of social investing and it still makes sense to many responsible investors who choose to put their capital into finance businesses.

Popular with investors

As the GIIN/JP Morgan survey indicates, there are also practical reasons finance is attractive to impact investors. Microfinance, according to their information, appeals to “closer-to-market” investors while financial services attracts “competitive return” investors. Although the research sample isn’t large, the findings indicate a reality: As one of the longest-established sectors of social investing, finance now has a track record. With experienced service providers like the Grameen Bank, Triodos and PAX World returning stable profits over a number of years (17 years in the case of veteran Grameen), finance has made a place for itself as a mainstay of impact investment portfolios that may also include riskier and low-return investments.

Financial provision has also proven a flexible tool the face of a changing world, especially in an era where the practice of economics is seen as an important lever for social change. Recent years have seen an explosion of innovative ways to “do” finance using models designed to reach underserved markets, especially ones in developing economies. Today, alternative finance intermediaries, including banks and insurers, are proliferating across the social investing sector and impact investors are following that expansion.

This trend reflects a deeper development in the social investing space. Once a controversial idea, now the notion that financial services are a necessary part of human life — or even, as Nobel Laureate Muhammed Yunus states, a “human right” — is widespread. Social finance in all its forms is one of the most familiar aspects of the social investing movement in the eyes of the public, for whom many of its more arcane forms, like catalytic capital and public-private partnership deals, are too complex to grasp and hold little human interest.

But which types of financial services are popular in the impact investing sector? And how is the relationship between impact investors and financial service providers set to change in the future?

To find out, see part two of this series: A Guide to the Different Forms of Impact-backed Finance and part three: The Future of Investable Social Finance.

Find impact deals in financial services.

Image credit: Copyright: bartderijk / 123RF Stock Photo

About the author: Marta Maretich writes about impact, sustainable and social investing for Maximpact.com, a deal listing portal and information hub for the new finance sector. She is Chief Editor of the Maximpact blog.

About Maximpact: Maximpact is a free global portal for the social, impact and sustainability sectors. It operates as a secure web-based listing service that allows sustainability, philanthropy and CSR professionals, as well as entrepreneurs, intermediaries, and funds to share information about initiatives and impact investment deals, online. For more information on the platform or to review latest impact projects visit: www.maximpact.com. This article first appeared on Maximpact’s blog.

Raising Dough: Two Bakery Chains Drive Social Innovation

By Annika Hoeltje

The Social Innovation Summit in NYC brings together organizations that aim to scale their social impact, such as the two large bakery chains Greyston Bakery and Panera Bread. Both are utilizing their core competencies in order to drive positive social change and community development. Greyston Bakery provides jobs and training opportunities for people, who haven’t been given a chance before, and Panera Bread addresses the problem of food insecurity in their community cafes.

Greyston Bakery creates apprenticeships for people who might otherwise not get the opportunity, so that they can move forward on their path to self-sufficiency. The certified B Corporation provides integrated training programs for individuals such as Dion Drew. After leaving jail in 2008 it was very hard for Dion to find a job that paid a salary he could survive on or that would enable him to start a family. Greyston Bakery took him on as an apprentice. During his yearlong apprenticeship he learned patience, self-discipline and a new attitude. He successfully completed the training program and was later promoted to the position of Lead Operator in the Research and Development Department. Dion finally had the means to support a family and his first child, a daughter, was born in 2010. The training program provided structure, taught him applicable hands on skills, and let him contribute to the making of high quality products.

Greyston Bakery shows how vocational training can open up opportunities for people that want to turn their lives around. This is a great example of how a company can tackle one of America’s most pressing social challenges, while operating a profitable business.

Another example for creating social impact is Panera Bread. Panera founder and CEO Ron Shaich believes that everyone deserves a dignifying dining experience in an uplifting environment regardless of their means. According to Shaich, one out of six people in the U.S. live in food insecure homes. At the Social Innovation Summit, he explained how this unique purpose guides the organization’s new initative, Panera Cares: At Panera Cares cafes guests will find the same menu of freshly baked goods, but no set prices. Instead they pay what they can into a donation box based on the honor system.

Panera didn’t just want to give left overs to homeless shelters – the company wanted to connect with those suffering from food insecurity. Panera opens up a new bakery café every 72 hours and Shaich wanted to apply this knowledge and skills to have a direct impact. He says: “It’s not just about feeding people’s bellies but also about raising their dignity.” In order to alleviate the social pressure no one can see how much a customer actually pays or donates. In order to sustain the bakeries, Panera Cares cafes are located in economically diverse neighborhoods.

Shaich said he learned a lot about his customers, his staff, and about the nature of humanity. He points out the following lessons from his pursuit for social innovation and impact. A company should:

- Identify its unique purpose and impact goal.

- Utilize its core competencies when innovating for social impact

- Pilot one impact project first and be prepared to fail fast and reiterate constantly.

- Raise awareness and challenge other organizations to do the same.

At the Social Innovation Summit both bakeries showed how they innovate in order to grow their business and their social impact. The next Social Innovation Summit will be in Silicon Valley in November.

Image courtesy of Panera Bread via Facebook

Annika is a consulting and cross-cultural project management professional with experience in Germany, India, China, Costa Rica and the U.S. She is passionate about social innovation, sustainable and change management, employee and stakeholder engagement, as well as organizational development. Annika recently finished her MBA in Sustainable Management and is based in San Francisco.

Interview: Dan Persica, Domtar

TriplePundit attended Sustainable Brands 2014 in San Diego this month. These videos are part of our coverage. Find the rest here.

We've been getting to know the paper industry a bit better in the past year. It's always refreshing to hear a first hand account of what sustainability means for a fiber or paper company. Last week at Sustainable Brands 2014, I had a chance to talk to Dan Persica of Domtar. Specifically we discussed Domtar's earth choice brand and how it has evolved over time as well as some of the ways that Domtar is tracking sustainability metrics and what the future holds.

Apple faces renewed calls to address worker safety

Environmental and human rights organizations, socially responsible investment firms, and occupational health professionals from 27 countries have sent a letter to Apple vp of environmental affairs Lisa Jackson, the former head of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), urging her to live up to her legacy by halting Apple’s suppliers using toxic chemicals in China.

At the EPA, Jackson monitored benzene levels in the water and air to ensure no one was exposed to dangerous levels of this known human carcinogen. According to the groups, Apple’s workers could be exposed to more than three times the amount of hazardous chemicals legally permissible in the US. They also estimate that the move to safer chemicals is less than $1 per device.

“As a global technology leader, Apple can and should be the first consumer electronics company to implement reforms to protect workers from hazardous chemicals,”, said Elizabeth O’Connell, campaigns director for Green America. “Apple has the financial resources to make these changes and the global leadership to make it count. Apple is not alone in these offenses, but its leadership is needed to make worker health and safety reforms a broader priority within the technology industry.”

Apple maintains that it requires its suppliers around the world to meet or exceed US safety standards.

Investor Ready Cities: From London to Rio de Janeiro

Ed note: This article is part of a short series on financing smart city infrastructure, sponsored by Siemens. Please join us for a live Google Hangout with Siemens, PwC and Berwin Leighton Paisner on June 12 at 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET, where we’ll talk about this issue live! RSVP Here.

Yesterday, we went over a few success stories told in timely and valuable report from Siemens, PwC and Berwin Leighton Paisner. Entitled Investor Ready Cities: How cities can and deliver infrastructure value, the report examines in some detail how cities that have “the appropriate foundations of institutional stability can leverage financial mechanisms to their advantage to help deliver the infrastructure that is so critical to their future.”

Here are three more inspiring snapshots that tell the story of cities moving towards a more sustainable future.

Medellin

The second-largest city in Colombia, with a population of nearly 2.2 million in 2005, saw a threefold increase in population over a 20-year period. This came at a time when governance and power was concentrated at the national level and control of financing was distributed to nationally important projects. As a result, informal settlements appeared on the city fringes and up onto the precarious hillsides that surround the city, leaving residents disconnected from the commercial heart of the city and the employment opportunities they had sought to access.

“Poor infrastructure and lack of opportunity led to Medellin experiencing some of the highest levels of crime endured by any city across the globe,” according to the report.

In 1991, a new constitution increased the influence and powers of municipal governments. For Medellin, this meant the power, authority and responsibility to tackle these issues through strategic intervention that was to literally change the city landscape.

Starting in 2000 and over the next 10 years, a succession of mayors created and implemented an integrated urban development plan. The vision encompassed a comprehensive strategy that sought to tackle issues facing the most deprived neighborhoods of Medellin and to identify solutions to the growing problem of poor connectivity, education and governance, and the use of public space. PUIs (Integral Urban Projects) were identified, introducing major infrastructure projects; these projects also provided an anchor for local development and a catalyst for the enhancement of public and green space. The plans sought to recover the most marginalized areas of the city, in an effort to invigorate local communities and re-engage the dispossessed.

The first major infrastructure project to take place under the PUI was the gondola system ‘Metro Cable, Linea K.' The cable car, opened in 2004, stretches 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) into the neighborhood of Santo Domingo -- creating a link directly from the city center to one of the city’s poorest areas. Travel times of up to 2 hours were reduced to 7 minutes on the cable car.

“As a transport solution success, it is worthy of recognition in its own right, but when delivered in conjunction with the urban development plan, the story is one of social mobility and revived community integration that is far greater than the transport story alone,” the report says. Cable car stations were made places of social integration through IT training and an adjacent library.

By connecting communities, the report continues, there has been a significant decrease in the levels of crime, with violent crime reduced by nearly 80 percent. “Commercial activity is said to have increased by 400 percent, and new businesses have developed along the route of the cable car, creating employment for less skilled workers.”

Medellin has demonstrated the “benefits of applying the ‘correct’ solution for its city, which as a consequence has made Medellin one of the most vibrant and commercially active cities in Latin America.”

London

Transport for London (TfL), a statutory body that was set up in 2000, is responsible for the planning, delivery and day-to-day operation of London’s public transport system. Its main mission is to provide or secure the provision of public transport passenger services to, from or within Greater London. TfL’s largest current infrastructure project is Crossrail, which involves construction of 21 kilometers (13 miles) of new twin-bore tunnels under central London, construction of nine stations and procurement of new rolling stock. Services are expected to start in 2018.Each train will carry 1,500 passengers, with peak services of 24 trains per hour in each direction. The projected cost is pegged at £15 billion ($25.2 billion), and it is currently the largest construction project in Europe. Funding at that level requires a variety of channels: More 60 percent of Crossrail’s funding will come from Londoners and London businesses, through fares. Also, “value capture schemes” have been set up: compulsory developer contributions as part of a Mayoral Community Infrastructure Levy; and a more generally levied Crossrail Business Rate Supplement. There will also be a grant from the central government. Financing has included a loan of £1 billion ($1.7 billion) from the European Investment Bank to TfL, one of the largest loans the bank has ever made.

“The success of TfL is a good example of the benefits of enabling holistic city wide control and decision making over the most important modes of transportation,” the report concludes, because efficiency, evolution and innovation are thus enabled. “The model of a transport body with cross-modal powers, the ability to raise finance directly in capital markets and answerable to city rather than national politicians is one that has broad relevance to major cities.”

Thameslink is the key north-south rail corridor running through central London and the South East of England; it carries more than 50 million passengers per year. Along London’s key commuter lines, increasing demand and aging infrastructure have contributed to overcrowding and delays. “Because of this, improving the quality of London’s key rail services, such as Thameslink, has been highlighted by a succession of U.K. governments as a top transport priority,” the report notes.

In 2005 the DfT took control of control of Thameslink as sponsor in order to manage the delivery of needed upgrades. Two years later, DfT laid out its plans for the Thameslink Program as part of its wider rail infrastructure and funding policy initiative. This included £6.5 billion ($10.9 billion) worth of commitments to upgrade the Thameslink infrastructure and procure new rolling stock through the Thameslink Rolling Stock Project (“TRSP”).

Following a competitive bid process, the TRSP contract was awarded to the Siemens-led Cross London Trains Ltd. consortium last year. To finance the project, a Private Finance Initiative/Public-Private Partnership (PFI/PPP) arrangement for lease of the rolling stock and the two depots was put in place.

These leases, together with the maintenance of the trains over a period of 20 years, have an aggregate contract value of £2.6 billion ($4.4 billion) in present value terms discounted to 2013 prices. Siemens Financial Services and its Cross London Trains consortium partners (3i Infrastructure and Innisfree), the DfT, and a syndicate of 19 banks worked to close the deal.

Financing major developments of rail infrastructure “presents many complex challenges, requiring significant planning, a well thought-out solution and skilled execution teams,” the report says. The conclusion: “Managing multi-stakeholder partnerships is critical for major infrastructure projects in order to develop realistic project-delivery milestones and build robust contingency plans. Furthermore, coordinating these partnerships so that interests are closely aligned and communicated is vital to keeping major infrastructure projects on-track throughout financial negotiations.”

Rio de Janeiro

Rio’s port area was traditionally a dynamic area that connected the city to international trade routes. That all changed starting in the 1970s, and the port entered the 21st century with vast stretches of underutilized and degraded areas, poor infrastructure and sanitation, and derelict historic buildings.

Enter the $3.5 billion Porto Maravilha (Port of Wonder) project. It is “central to the regeneration of Rio’s physical and social infrastructure,” the report says. By regenerating the port, Rio is using the only centrally located area available for substantial development while also refocusing commercial growth back into the city center and supporting greater transport integration.

When completed in 2016 the port will have 1,235 acres of modern infrastructure and mixed-used real estate. This will be accomplished through the use of CEPACs, or Certificates of Potential Additional Construction, that are issued by municipalities. They are used to finance building projects and infrastructure development within a particular area through sale of real estate development rights. Within Porto Maravilha, Caixa Economica Federal (CEF) — the Brazilian Federal Savings Bank — took up all CEPACs issued from Rio City Hall. CEF did this through a specifically created fund – the Porto Maravilha Real Estate Investment Fund (FII), which is able to sell CEPACs directly to developers or otherwise bring engage them for joint venture purposes “both to help make a market and to capitalize on market buoyancy.”

The report concludes that Porto Maravilha “is an excellent example of an holistic approach to city-led regeneration and infrastructure delivery,” because it combines urban project legislation; land use zoning; real estate tax breaks; creation of an urban development company, real estate investment fund and PPPs; strategic use of public land and tradable financial instruments.”

As a result the City of Rio is able to use new and existing assets to leverage private investment; to stimulate regeneration through strategic infrastructure investment; to direct of development activity; and to share in value uplift through strategic land disposal, joint ventures and CEPAC trades.

Image credit: Flickr/sico_activa

Join Triple Pundit for a live Google Hangout with Siemens, PwC and Berwin Leighton Paisner on June 12 at 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET, where we’ll talk about how to finance cities of the future.

Employee Engagement: The 'Human Thread' Between Sustainability and Results

The 2014 Sustainable Brands conference in San Diego gathered some of the most influential companies, organizations and thought leaders in the sustainability space. During the event, one unexpected theme arose over and over: employee engagement and its role in corporate sustainability.

A recent PwC study found that more than half of recent college graduates are seeking a company that has corporate social responsibility (CSR) values that align with their own, and 56 percent would consider leaving a company that didn't have the values they expected. As Andy Savitz, author of "Talent, Transformation and the Triple Bottom Line," put it in a panel discussion on Tuesday: "They're looking for purpose, not just a paycheck."

While some business leaders may have a first-instinct shrug when it comes to employee engagement, it offers scores of benefits for companies. In a 2012 report that compiled 263 research studies across 192 companies, Gallup found that companies in the top quartile for engaged employees, compared with the bottom quartile, had 22 percent higher profitability, 10 percent higher customer ratings, 28 percent less theft and 48 percent fewer safety incidents.

In a panel discussion on Tuesday, Desso CEO Alexander Collog d'Escury called employees a company's "most important resource," while Savitz identified employee engagement as "the human thread between sustainability, the triple bottom line and business results."

In the past, the best 'business cases' for sustainability focused on cost savings. It makes sense: When a company reduces environmental impact, it ups efficiency, reduces waste and reaps the financial benefits. But in recent years employee attraction, engagement and retention has caught up to -- if not surpassed -- cost savings as the driving factor influencing companies to embrace sustainability goals.

"I hear this a lot in companies: The ability to attract and retain really good people partly depends now on how you're managing [the world's] mega challenges," Andrew Winston, environmental strategy consultant and author of "The Big Pivot," told Triple Pundit in a recent interview. "Companies are hearing this in recruiting, even from the millennials who are desperate for jobs."

While brand values are surely important to millennials entering the job market, it's worth noting that those PwC figures are down from a much more substantial 88 percent in 2008. (The drop may be thanks to a job market that hasn't been too kind to recent grads; more than 25 percent are unemployed or underemployed, compared to just over 10 percent in 2000.)

In its report, PwC noted that the importance of corporate responsibility in attracting and retaining young talent is "waning" in raw numbers alone. But in an exclusive interview with Triple Pundit, Clinton Moloney and Amy Longsworth of PwC championed employee engagement as crucial to a company's success -- and said in no uncertain terms that corporate responsibility will only become more important in achieving it.

"Wherever you are in an enterprise, everybody wants to be part of something positive," Longsworth told Triple Pundit. Moloney agreed, pointing to PwC's emphasis on sustainability and social responsibility in its own recruiting.

"This is a critical part of the strategy for our own firm," Moloney said. "We're the No. 1 on-campus recruiter in the United States. So, if you're trying to hire the best and the brightest all over the country, [one of] the distinguishing factors that set us apart from our competitors is that we not only do the sustainability work with our clients, but we do a great deal of it for ourselves."

In its most recent move to bolster employee engagement around sustainability while doing social good, PwC made a $150 million commitment over five years to drive up volunteerism in the company. The program, called Earn Your Future, allows PwC employees to increase financial literacy in children and teens by creating lesson plans for students of all ages.

"What we've seen is the leaders of our 20-something offices compete on how many hours they can get volunteered to deliver the Earn Your Future program, so it's actually a core success metric for our most senior partners," Moloney said. "The advantage is: Next time there's an economic downturn, we're not going to defund this because it's seen as critical to our long-term success. So if you can get all these things in alignment, that's what I think true sustainability is."

In his discussion, Savitz listed off a number of similar initiatives enacted by other forward-looking companies -- such as Timberland, which surpassed 1 million volunteer hours served, and Patagonia, which boasts more than seven ways for employees to get involved in social and environmental good.

A program like Earn Your Future makes sense for PwC, but Longsworth noted that it's important for companies to find programs that resonate with their own core values and those of their employees. As Savitz put it bluntly in his discussion: If a company isn't allowing its talent to engage in sustainability at the workplace, "someone else will."

As I listened to Moloney and Longsworth speak about the Earn Your Future program, it was easy to see that both were happier employees as a result of the company's commitment -- a testament to the benefits such programs can have on employees.

"I love telling this story because it's exactly the kind of stuff we would love our clients to adopt, and I'm very proud to be in a workplace where I feel we can lead by example," Moloney said. How's that for an engaged employee?

Stay tuned for more coverage of the 2014 Sustainable Brands conference all week on Triple Pundit!

Image credit: Sustainable Brands via Facebook

Based in Philadelphia, Mary Mazzoni is a senior editor at TriplePundit. She is also a freelance journalist who frequently writes about sustainability, corporate social responsibility and clean tech. Her work has appeared in the Philadelphia Daily News, the Huffington Post, Sustainable Brands, Earth911 and the Daily Meal. You can follow her on Twitter @mary_mazzoni.