Save the Children, IKEA Foundation Redouble Efforts Against Child Labor

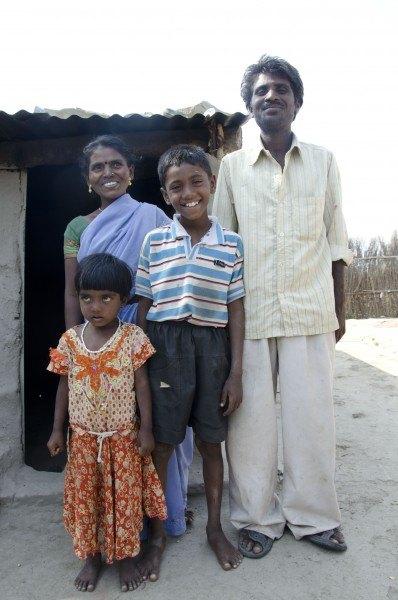

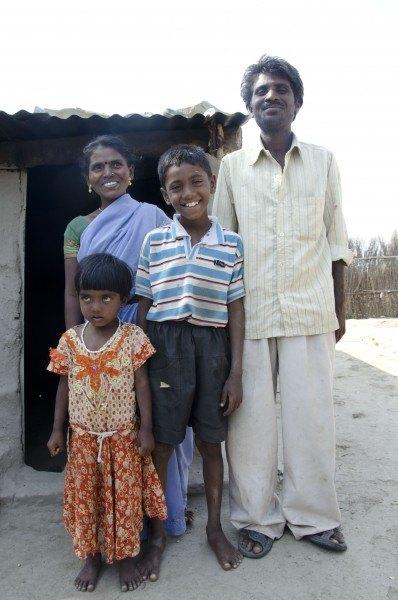

In honor of World Day Against Child Labor (June 12), Save the Children and partners Breakthrough, Pratham and the IKEA Foundation announced the €7 million second phase of their program to combat child labor and promote education in cotton communities in India. There are an estimated 12.6 million child laborers in India between the ages of 5-14, many who are involved in the cotton industry, working under deplorable conditions sometimes more than 12 hours a day. This program is working to bring children back to their communities and families, put them in school and allow them to be children.

The first phase of this long-term program, started in 2009, impacted more than 1,800 villages and 600,000 children in the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. The second phase aims to reach more than 790,000 children in Punjab, Haryana and Rajasthan. Thomas Chandy, CEO of Save the Children, said, "We will work closely with panchayat (village) leaders, farmers, teachers, families and Indian state officials, to provide children with access to quality education, improve teacher training and develop local child protection committees and school management committees." New to phase II, the program will also address gender-based discrimination.

Working from a successful foundation

“The IKEA Foundation is committed for the long-term to impacting child labor. We are focusing on making sure phase II is successful and builds on the positive impacts from phase I,” said Jonathan Spampinato, Head of Communications and Strategic Planning.

Accomplishments from phase I include:

- Creation of community groups to protect children. Comprised of parents and community members, these groups give a voice to members to guard the welfare of children in the community.

- Enrollment increase in schools. Among six-to-ten-year-olds, enrollment rate in villages that participated in the program was 92 percent, five percent higher than villages outside the program. Among eleven-to-fourteen-year-olds, participating enrollment rate is 89 percent, four percent higher.

- Communities monitoring schools and teachers. Newly created groups give parents a say in running the schools and aim to bring working children back to school.

- Abolishing inter-state migration. Phase I initiatives along with government interventions contributed to reducing children's migration between states to work in cotton. A baseline survey estimated 10,000 children migrated to work as laborers, while an impact assessment after phase I indicated almost a complete cessation of child migration in and out of program districts.

- Training of anganwadi workers and teachers. Nearly 2,000 Anganwadi (childcare centers for children under six) workers were taught methods to make classroom learning more compelling.

- Development of training materials. Phase I developed training materials that have been used by the Gurarat and Maharashtra governments and UNICEF.

In these regions, there is also the deep-seated issue of gender discrimination that starts before birth, severely limiting girls' opportunities for education and growth. Indeed, recently India has been in the spotlight due to attacks on women. In both Punjab and Haryana, girls outnumber the boys among child laborers (sometimes even double the number) and the sex ratios are the lowest in the country at 834 and 846 per 1000 male children (2011 census). In addition, Sex Selective Elimination (SSE), the practice of aborting girls in favor of having more boy babies, has lead to the decline of the number of girls in recent decades.

Phase II aims to combat gender-based discrimination in the schools, developing elementary school materials designed to address attitudes about girls and their place in society. Newly established youth clubs will also champion girls' rights and encourage girls to pursue educational opportunities.

The final program effort will be to interact with entire communities using mobile street theaters along with art, games and social media activities. Breakthrough's multimedia van will travel to participating communities to raise awareness about children's rights and gender discrimination through the use of educational videos and interactive activities like plays and other performances.

“We know there is no quick-fix solution to ending child labour, but long–term approaches can yield impressive results,’’ Per Heggenes, CEO of IKEA Foundation explained in a press release. “The IKEA Foundation, with our partners, has been tackling this issue in India for nearly a decade. This new phase reinforces our long-term commitment and our desire to help millions more children out of child labour and back into the classrooms.”

Healthy Forests Promoted Under California Cap-and-Trade

By Christine Yankel

April marked a milestone for forest carbon projects when the California Air Resources Board issued the first forest carbon offsets to a project developed under their forestry protocol.

The Yurok Tribe Sustainable Forest Project improves forest management on approximately 8,000 acres of tribal land in Humboldt County. By registering the project and selling carbon offsets in California’s cap-and-trade system, the Yurok Tribe has made a long-term legal commitment to not only maintain forest carbon stocks, but to increase storage of carbon through improved forest management. These practices enable sustainable timber production, and promote preservation of cultural values and ecological function. Improved management is also key to preserving important habitat for Coho and Chinook salmon, with additional benefits to other imperiled species.

“This forest carbon project enables the Tribe to help transition these acres back into a tribally managed natural forest system where wildlife and cultural resources like tanoak acorns, huckleberry, and hundreds of medicinal plants will thrive,” said Thomas P. O’Rourke, Sr. Chairman of the Yurok Tribe, as reported by Gloria Gonzalez in Ecosystem Marketplace.

The sustainable forest project is notable as a pioneer in this sector -- demonstrating the complex and varied demands we place on forests. The project also exemplifies the important role carbon finance can play to diversify revenue and to tip the balance toward sustainable management with both local and global benefits.

We need healthy forests. The Environmental Protection Agency reports that the U.S. forest products industry produces $200 billion in sales each year and employs about one million workers. At the same time, healthy, ecologically sound forests are among our most important carbon reservoirs; removing CO2 from the atmosphere and storing it for the long term, ultimately helping to lower emissions globally.

While the verification of this project is a critical step in the maturation and growth of the young California carbon market, voluntary carbon market standards continue to play a vital role for forests. Although the Yurok project is the first project to produce offsets under the compliance protocol, other forestry projects, called Early Action projects, have already been issued California Compliance Offsets by converting offsets that were first generated and qualified under voluntary standards.

All together, the Yurok project and Early Action projects (with offsets issued by the Air Resources Board) currently only cover about 67,000 acres of forest. While other Early Action and compliance projects are working their way through the carbon market process, well over 750 million acres of forest in the U.S. alone face multiple demands that can lead to forest degradation and loss.

Diverse options that can support improved management and conservation are needed. There is also a need for innovative and quality standards that open the market’s potential to serve new groups or that streamline participation by small forest owners. Protocols of this kind are being developed and vetted under the American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve and Verified Carbon Standard. Globally, carbon finance from varied standards impacted nearly 28 million acres of forests in 2012.

Carbon markets, like forest management, require balancing many demands. Considerations include environmentalists’ need for assurance of scientific rigor and environmental integrity of offsets, as well as ensuring that project transaction costs and management requirements are not so rigid that they prevent adoption of improved systems supported by carbon finance. It's not an easy balance, but by bringing together diverse voices, and learning from successful projects and challenges in carbon markets, more good, innovative forest projects can take root, branch out, and grow.

The Climate Trust is committed to partnering with both quality voluntary and compliance carbon offset projects to advance these scalable solutions for the betterment of our forests and planet.

Image credit: Nicolas Boullosa, Flickr

As a Senior Project Analyst for The Climate Trust, Christine is responsible for managing their growing greenhouse gas emission reduction project portfolio and providing technical support on forestry initiatives. Prior to her time at The Trust, Christine worked as a project manager and supported monitoring and training for a project that empowers smallholder farmers in East Africa and India to improve their farms and gain new income from the carbon market by planting trees on their farms.

Business Inspired By Nature

By Giles Hutchins

Can business be a force for good -- restoring society and the environment and providing solutions that genuinely help rather than hurt? Ought business to be striving for more than just limiting its harm? I think we intuitively know it can, yet it requires courage to break rank from our mainstream approach and current mindset.

The prevailing business paradigm of maximization, self-interest and short-termism is weakening its own resilience, in turn sowing the seeds of its own demise. Our prevalent business concepts, values, perceptions and practices are being disrupted and systemically challenged. Put simply ‘business as usual’ is no longer an option for those wishing to thrive in the volatile times ahead.

As individuals and organizations, we can either a) retrench (clinging fearfully to outdated mindsets) or b) transform (embracing new ways of operating). It reminds me of the ancient Chinese Proverb:

In times of great winds, some build bunkers others build windmills.

Organizations have little option other than to seek out opportunities in these volatile times, adapt and evolve to what the book "The Nature of Business" refers to as ‘firms of the future’ – businesses more akin to living organisms than mechanistic monoliths designed for the Industrial Era. These firms of the future can take inspiration from nature at all levels within their strategies and operations. For instance:

Places: Intelligent buildings that sense and respond to their environment are effective, vibrant and healthy places to work.

Products: Biomimicry is already well established in assisting the designing of sustainable products – just Google ‘biomimicry’ to come up with many examples.

Processes: Industrial ecology and symbiosis, business ecosystem mapping, systems thinking, eco-literacy, circular processes, closed loop economics and cradle-to-cradle are part of a growing list of approaches applied to shaping business processes based on insights from nature.

People: Traditionally the domain of humanists and psychologists, more and more we find nature’s inspiration positively influencing how we engage, empower and encourage our people to build resilience within their diverse stakeholder group. For example eco-psychology and natural leadership are emergent approaches to help business people deal with complexity and unpredictability

Purpose: As organizations recognise the need to have a higher purpose beyond ‘short term profit maximisation’ in order to galvanise themselves for the stormy seas ahead, many in business question whether it is ‘good enough’ to focus on becoming ‘sustainable’ by focusing on reducing negative social and environmental impacts. Some forward thinking businesses are realising that ‘reaching beyond zero impact’ means becoming restorative and net positive, where business creates conditions conducive for life, rather than merely reducing the harm inflicted.

Diversity, flexibility and inter-relations, we find, are core to the interwoven evolutionary journey of life – the driving forces that provide resilience and regeneration. Yet, the prevalent approach of business (and for that matter human society) sets itself a part from nature. How, then, can we set about attuning our approaches to the inherent grammar running through life?

This question of the moment can be answered through 3 R's – Re-design, Re-connect, Re-kindle:

- Re-designing - new ways of operating and innovating beyond 'less bad' into 'doing good' (shifting from the take/make/waste economic paradigm to a regenerative approach that heals society and the web of life rather that destroying life in the name of short-term gain). An example here is the Kingfisher Group aiming to be a ‘net positive’ force for good in the world.

- Re-connecting - reconciling our human relationship with life/nature and our own authentic human nature (re-establishing our vital bond with ourselves, our neighbours and the web of life within which we are a part of through education, authentic leadership and eco-psychology). An example here is the co-founder of Natura, Pedro Passo, who instils a business culture that understands our interrelatedness with nature and community.

- Re-kindling wisdom - working with the grain of nature and operating within the rules of life on Earth (enabling businesses and societies not merely to ‘sustain’ but to thrive in the years ahead by practicing wise approaches to life that draw on, for instance: symbiosis, ecological thinking, permaculture, systems-thinking and systems-being, business inspired by nature, presencing & indigenous wisdom). An example here would be Weleda with its bio-dynamic philosophy and its holistic approach to all aspects of its business.

U.N. IPBES Aims for Indigenous Knowledge-Science Synthesis

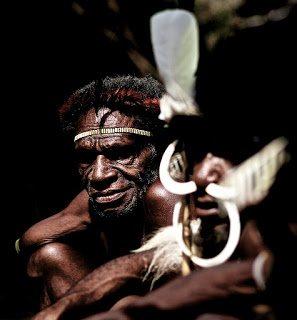

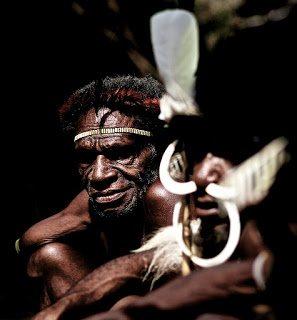

Given our dependence on the products of highly sophisticated science, engineering and technology, it's easy to pay short shrift, or look askance, at the value of traditional indigenous knowledge. To be sure, the depth and scope of our knowledge has advanced rapidly. Yet, this type of arrogance, or hubris, not only takes away all that could be gained scientifically and socially from an unplumbed yet certainly rich cultural heritage, but may leave us more open to being blindsided by “black swans.”

Traditional indigenous knowledge, as well as human resources, holds particularly high value with regard to ecological and species conservation, and efforts to preserve rapidly diminishing biodiversity. Still directly connected with natural ecosystems for their livelihoods, the practical, everyday ethics, values and attitudes of traditional indigenous cultures can also inform and motivate our quest to enhance the overall sustainability of modern life and society, and add shared value and meaning to them.

Looking to tap into and incorporate traditional indigenous knowledge into its institutional framework, the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity's (CBD) Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) convened an international expert workshop on the contribution of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) to IPBES in Tokyo June 9-11.

Science, indigenous peoples and conserving biodiversity

With 194 United Nations (U.N.) member countries and the EU parties to it, the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity is the principal multilateral treaty for governance of biodiversity. Modeled after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the recently established Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is its operational branch.

With species and biodiversity diminishing at alarming rates, the CBD secretariat, along with agencies including the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP), has been expanding efforts to incorporate traditional indigenous knowledge into the process of formulating treaties and policies regarding international environmental governance, as well as financing and otherwise supporting projects on the ground.

As UNEP reports in The Contribution of Indigenous and Local Knowledge Systems to IPBES: Building Synergies with Science:

“In the face of unprecedented declines in biodiversity over past decades, it has become increasingly apparent that synergies must be built among knowledge systems in order to provide policy-makers and science practitioners with the best available knowledge to decide what urgent action must be taken to halt the rapidly accelerating degradation and loss of the biodiversity and ecosystem services that underpin sustainability, as well as resilience in the face of global change.”

Integrating indigenous and local knowledge with modern science

Toward that end, participants at IPBES' expert meeting in Tokyo began a process to officially and formally incorporate indigenous and local knowledge into the organization's emerging institutional framework for multilateral biodiversity and ecosystems services governance. Two initial recommendations broadly set out the means of doing so:

- Recognizing that indigenous peoples and members of local communities have distinct status as knowledge-holders and rights-holders; and

- Putting in place mechanisms and procedures to ensure effective participation in the MEP (Multidisciplinary Expert Panel) itself and its activities, including in any working groups, expert bodies and other structures that may be established, in the development of the conceptual framework and work program, as well as in outreach to indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs).

A commitment to gender equality was also elaborated. As stated in UNEP's report, “Women and men commonly fulfill different, but complementary roles and responsibilities in relation to different components of biodiversity and sustainable use, resulting in different knowledge, needs, concerns, priorities and roles.

“For this reason, women may possess knowledge, not held by men, which can inform IPBES processes. To fulfill its operational priority to achieve gender equity in all relevant aspects of its work, IPBES should put in place mechanisms that ensure attention to gender specific-knowledge and gender balance in all components of its work.”

A commitment to undertake an ambitious work program aimed at integrating indigenous local knowledge with modern science also came out the expert meeting in Tokyo. This includes carrying out a scoping study “of existing experiences, approaches and methodologies on bridging between scientific and indigenous knowledge systems to better understand and assess status and trends with respect to biodiversity and ecosystems services.”

Concerned with issues such as bio-piracy, IPBES also made a commitment to enhance efforts related to intellectual property rights, access and benefit-sharing, and free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), the fundamental principle underlying an ethical commercial framework for obtaining rights to make use of indigenous knowledge and methods, as well as products resulting from research on local flora and fauna.

Images credit: 1) The Coincidental Dandy; 2) The Global Change Project; 3) NovaMind

SolarCoin: Good for the Environment but Not Social Equity?

Editor’s Note: To learn the basics of SolarCoin and catch up on the first four posts in this series, check out the SolarCoin page at theblisspoint.org.

By Sam Bliss

SolarCoin rewards solar power producers. The early adopters of a technology that helps slow climate change and brings clean electric power to new people deserve a reward, right?

Handing out digital cash to people with solar panels can benefit our electricity systems and the environment, but there might be more equitable ways to incentivize clean energy.

Getting SolarCoins

New SolarCoins enter the online "money supply" when they're granted to the residents of a property with a solar installation or to the owners of a large solar project. In essence, a new piece of electronic money is created and then given to someone who has enough money to own or lease a solar system.

SolarCoins offer a new source of income -- and eventually wealth -- that can be accessed most easily by those who already have plenty of income or wealth.

For people without solar panels or investments, on the other hand, the only way to get some of this newly created value is by exchanging another currency like dollars or Bitcoin for SolarCoin in an online currency exchange. As of yet, there's no way to turn dollars or any other national currency directly into SolarCoins; one must get bitcoins first and then trade for SolarCoins.

Exclusionary opportunity

As SolarCoin scales up and increases in value -- assuming that it does in fact become popular -- opportunists, cryptocurrency fans, and clean energy advocates will earn income just by holding SolarCoins. Digital currencies are a means of exchange as money, yet in these early days they are more like assets than stable stores of value.

Yet access to SolarCoin, like so many of the most lucrative investment opportunities in today's economy, is exclusive to those who are already at least somewhat well-off. SolarCoin grantees have a solar-paneled roof over their heads or an ownership stake in a solar project, pieces of capital that earn plenty of income just from electricity sales.

For those who do not have sufficient wealth or access to capital to become solar power producers, getting SolarCoins requires extra money with which to buy them. Those who must spend all their income on food, rent, cell phone service, electricity, transportation, heating fuel, and modern life's other necessities don't have cash lying around to turn into SolarCoins.

In addition, it takes some degree of technical competency to get your hands on any 'cryptocurrency' -- even the widely popular Bitcoin. Exchanging bitcoins for SolarCoins requires further knowledge and training to navigate complex online currency markets like Bittrex, a site whose esoteric charts and unexplained tables appear quite foreign to someone not versed in trading currencies or assets on the web.

Accelerating inequality

In short, wealthy people with leisure time have an distinct advantage in filling their digital wallets with SolarCoins. In a society where the vast income chasm separating high earners from the rest of us grows every year, introducing another instrument that make the rich richer deepens the problems that threaten capitalism instead of working toward fixing them.

Without mechanisms for extending access to the means of producing solar power to poor people neglected by the private banking system, SolarCoin speeds up the rate at which wealth concentrates among the fortunate few. Yet there are some promising developments that can counteract this troubling phenomenon.

The next post in the series will explore existing and potential strategies that make SolarCoin accessible to everyone. Stay tuned!

Sam is an aspiring economist and writer. You can read his work at theblisspoint.org. Sam’s digital wallet does not yet hold any SolarCoin thanks to his technological incompetence, but you can help change that — simply send SolarCoins to: 8Rs7YHL4z5jeNenpMD3X4BnaMZstx7QwEk

Interview: Jeremiah Owyang, Crowd Companies

TriplePundit attended Sustainable Brands 2014 in San Diego this month. These videos are part of our coverage. Find the rest here.

Jeremiah Owyang is one of the most interesting people I had a chance to meet at last week's Sustainable Brands conference. An analyst by trade, Jeremiah now runs a network called Crowd Companies who propose to "bring empowered people and resilient brands together to collaborate for Shared Value." Specifically, this shared value springs from embracing the "collaborative economy" - a meta term for business models built on shared ownership and access. It's a somewhat more inclusive description of most of what we talk about when we talk about the sharing economy.

In this quick interview, I asked Jeremiah to talk about the collaborative economy - why it's important, why it's both a threat and an opportunity for traditional companies, and what it has to do with sustainability.

UK pension fund investments linked to unethical land grabs

UK pension funds and asset management companies could potentially have £37bn invested in ‘land grabs’ worldwide, according to a new report published by Friends of the Earth.

The report, What’s your pension funding? How UK Institutional Investors finance the global land grab, is the first time UK pension funds and asset management companies have been linked directly – via their investments – to global firms either known or alleged to be involved in cases of land grabbing from communities in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Household names including British Airways Pension Fund, Legal & General, Scottish Widows Investment Partnership and Aviva Investors have been identified in the report.

Land grabbing is when wealthy businesses purchase large pieces of cheap ‘unused’ land, often to grow crops for fuel and for other industries, and infringe the rights of the affected people and communities. This sometimes results in families being forcibly kicked off the land they are using to grow food and not being given compensation.

Friends of the Earth Land Grabs Campaigner Samuel Lowe said: “UK pension funds should not be investing our money in any company that puts potential profits above the livelihoods of people who live in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

“Our future retirement funds are often being secured at the expense of the poor and powerless through widespread land grabbing – in some cases our pensions are actually under threat of being wiped-out due to the risky nature of large-scale land acquisition deals.

“There needs to be stringent international laws to rule out all of the impacts associated with land grabbing – UK investors must stop funding companies linked to this scandal.”

Picture credit: © Ronfromyork | Dreamstime.com

Carney takes on co-presidency of Heart of the City

Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, has been appointed as co-president of Heart of the City, the charity that aims to put Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) at the heart of business.

Carney will join the Lord Mayor, Fiona Woolf, to share the responsiblity of presidency for Heart of the City, a 700-strong powerhouse of responsible business leaders, CSR practitioners and change agents committed to sharing their experiences and their time with others in order to measurably improve our society.

Heart of the City was launched in 2000 as a joint initiative of the Bank of England, City of London Corporation and Financial Service Authority.

“The Bank of England, notably through former Governor Lord George, has a long history of involvement with Heart of the City, and I am delighted to continue that tradition of support by serving as Co-President alongside the Lord Mayor," commented Carney.

"Lord George rightly believed that firms must recognise their responsibility for the broader system. Such a sense of the systemic is necessary in order to build and maintain social capital and contribute to inclusive capitalism. Heart of the City plays an important role in this regard, helping firms large and small to develop their corporate social responsibility programmes. I encourage all businesses to become part of its network and take full advantage of its broad range of resources and support.”

The U.S. Prisons Network: A Cheap Supply Chain with No Checks & Balances?

Submitted by Guest Contributor

By John Arvanitis

Activists, business executives and politicians alike acknowledge the United States incarcerates more people per-capita than any other nation in the world.

What is lesser known and discussed about our prison system is that more than two million people in state, federal and privately-owned prisons are subjected to a working situation that mirrors involuntary servitude. With numerous multinational corporations utilizing prison labor as a part of their supply chain, taking advantage of desperate prisoners who are willing to work in poor conditions for extremely low wages is easy and widely implemented.

In fact, companies who utilize prison labor are being afforded an unfair advantage while facilitating the violation of these people’s basic human rights.

But it wasn’t always like this.

A Brief Look Back

Prison labor in the United States began with the abolition of slavery.

The 13th amendment banned involuntary servitude except, “…as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been dully convicted…” Since 1865, this section of the 13th amendment and other legislation established prison labor as a legal means of economic activity in federal, state, and private prisons across the United States.

In the 20th century, this form of labor moved from a prisoner leasing system to a more diversified service and industrial paradigm that closely mirrors the larger United States economy. Incarcerated workers manufacture license plates and road signs, sew clothes, construct office furniture, assemble complex components for the United States military and even help maintain fish farms.

and industrial paradigm that closely mirrors the larger United States economy. Incarcerated workers manufacture license plates and road signs, sew clothes, construct office furniture, assemble complex components for the United States military and even help maintain fish farms.

Historically, private companies weren’t legally permitted to utilize prison labor since it was seen as an unfair advantage. This changed thanks to the American Legislative Exchange Council’s Prison Industries Act of 1995 and the federal program known as the Prison Industries Enhancement Certification Program or PIE.

The Prison Industries Act was designed to “provid[e] for the employment of inmate labour in [state’s] correctional institutions and in the private manufacturing of certain products under specific conditions.” The act also stipulated that “…inmates must be paid at the prevailing wage rate,” and “…any room and board deductions…are reasonable and are used to defray the costs of inmate incarceration.”

This law may seem reasonable, but its basis only worked to further exploit prisoners by deducting their wages to pay for room and board expenses, even while companies utilizing inmate labor received tax breaks from the federal government. In addition, the specifics of this act vary from state to state. For example, incarcerated people in Racine, Wisconsin have replaced workers at public institutions and aren’t paid for their work; instead they receive time off their sentences as compensation.

According to Mike Elk and Bob Sloan at The Nation, “The same is occurring in Virginia, Ohio, New Jersey, Florida and Georgia, all states with GOP Assembly majorities and Republican governors.”

The Reality of Prison Labor

In many ways, an incarcerated person represents the ideal worker:

- The prisoner is an individual among a workforce that is massive and growing.

- They have little to no union representation.

- They are desperate for work and willing to accept low wages and less-than-ideal working conditions.

- The contractor is not obligated to offer any benefits to the incarcerated person in regards to health care, sick time, worker’s compensation, paid time off, vacations, overtime, etc.

While some of these characteristics apply to workers outside the prison system, companies who choose to utilize prison labor have an unfair advantage over others. Moreover, access to prison labor is not a readily accessible to all organizations since companies must bid for contracts and maintain relationships with private federal and state prisons. Consequently, manufactures in economically depressed parts of the country are losing contracts to privately owned prison labor organizations like Unicor to produce goods for the federal government.

Today, most prisons require 100 percent of able-bodied incarcerated people to work. Physically forcing prisoners to work would not be legal;  instead, prisons indirectly coerce inmates into working. For example, if prisoners refuse to work, institutions can send inmates to solitary confinement or take away basic privileges ranging from television time to visitation rights. Prisons can also add 30 days to individuals’ sentences if they refuse to work since refusal is a violation of certain “good behavior” standards.

instead, prisons indirectly coerce inmates into working. For example, if prisoners refuse to work, institutions can send inmates to solitary confinement or take away basic privileges ranging from television time to visitation rights. Prisons can also add 30 days to individuals’ sentences if they refuse to work since refusal is a violation of certain “good behavior” standards.

And, it doesn’t stop there.

Prisoners who want to work also experience exploitation and must constantly negotiate the violation of their basic rights as workers.

For instance, if there is a lull in demand for specific products or services, companies can deny prisoners the right to work even if they were promised working hours in advance. Incarcerated people have little control over what kind of work they do and how often they do it since few prisons have collective bargaining agreements leading to dissatisfaction, confusion and conflict in the workplace.

The Main Culprits?

According to The Center for Global Research,

Major corporations profiting from [prison labor] include Motorola, Compaq, Honeywell, Microsoft, Boeing, Revlon, Chevron, TWA, Victoria’s Secret and Eddie Bauer.

IBM, Texas Instruments and Dell get circuit boards made by Texas prisoners. Tennessee inmates sew jeans for Kmart and JCPenney. Tens of thousands of youth flipping hamburgers for minimum wages at McDonald’s wear uniforms sewn by prison workers, who are forced to work for much less.

Here is a more exhaustive list of companies who currently utilize prison labor in some part of their supply chain.

In addition to the private sector partnerships though, federal, state and local governments also establish contracts with private prisons for various kinds of labor. In a strange tone, the Washington State Department of Corrections Private Sector Partnership asks potential clients,

“Are you experiencing high employee turnover? Worried about the costs of employee benefits? Unhappy with out-of-state or offshore suppliers? Getting hit by overseas competition? Having trouble motivating your workforce? Thinking about expansion space? Then Washington State Department of Corrections Private Sector Partnerships is for you.”

By now, you should be able to piece together the vicious circle occurring between labor, politics and the private sector. While prison labor can teach inmates valuable skills, prepare some for a life after incarceration and even bring dignity to them, it is not an excuse for exploitation.

There may come a time when prison labor is mutually beneficial but for now our current prison labor system works only to marginalize people’s basic human rights and exploit the unfortunate circumstances of incarcerated individuals while increasing the profits for a small part of the private sector.

About the Author:

John Arvanitis is a blogger, media relations newcomer, social justice advocate and student of sustainability. He’s a Western New England University graduate in Sustainability with a focus in Marketing and Management. John believes that we can build more sustainable communities through environmentally, economically and socially responsible business practices.

As an intern for nonprofit organization GreenWork, John managed social media accounts, publicized events, spearheaded community outreach and worked with the board of directors to create and execute a marketing plan geared towards increasing membership. Currently, John is working as an outreach intern for Co-op Power, working toward securing a sustainable energy future for communities across New England.

Much of John’s academic time is spent theorizing what a more sustainable global community would look like. According to John, sustainability is the simultaneous intersection of meaningful social progress, economic development and environmental protection. He hopes to work with more nonprofits, cooperatives, government agencies, for-profit institutions and other NGOs to foster sustainability and grow professionally.

Shop Your Values: What Does 'Sustainable' Really Mean?

How do you measure sustainability? Most of us would have two to four quick answers: Energy usage, quality of materials, longevity or carbon footprint.

Now, how exactly do you quantify that? In other words, how do customers figure out if a clothes dryer is going to use an affordable amount of energy and be worth the purchase? How do they know if that lotion or conditioner they bought is really made of ingredients that are not only healthy but okay for the environment once rinsed down the drain? What if they need construction materials that are mold resistant and won’t create allergens or decompose from humid weather?

The answer, says Scot Case, director of Market Development for UL Environment, is the same approach we have, for years, relied on to ensure that toaster in the kitchen is safe to use, or the inspection that was used when your office was wired for lighting: validation and certification that sets thresholds and manufacturing standards.

“So if someone wants to make recycled content claim,” says Case, “[UL Environment] can validate that claim. If they want to make an energy efficiency claim, or a biodegradability claim, or a compostability claim, we can validate those specific environmental claims [as well].”

In fact, UL Environment isn’t one broad-ranging certification program, but a composite of specialized processes that, as a whole, strives to address as many environmental concerns as possible. Its GREENGUARD label is one of its more unusual examples.

GREENGUARD has made substantial strides in recent years in developing markers that help us verify and quantify potential chemical emissions in our homes, what are called volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Through laboratory testing, researchers are able to measure those VOCs and, for example, determine the safety of a particular infant mattress or the paint a consumer is planning to use in the nursery. It’s able to establish safety thresholds and performance standards that 30 years ago may have seemed more like fiction than plausible science.

“So we can actually get detailed information about what [is] off-gassing from the product” (being emitted as VOCs) explains Case. “And that is proven to be particularly important in the green building sector, where they are trying to avoid sick building syndrome.” And it’s been particularly important to consumers who often want data before they buy a product.

Interestingly, the challenge that UL Environment often sees in the sustainability sector, says Case, is the confusion over what the ‘sustainability’ label means – and what it doesn’t.

“I think in its simplest form, the big challenge is that sustainability is a big, huge complex, interconnected subject,” says Case. “And most consumers only understand a narrow slice of it. Unfortunately, different groups of consumers understand different slices of sustainability.” Often that understanding may be determined by what the customer sees as most important to their environmental concerns.

“[Some] consumers understand things like recycled content, other consumers understand things like energy efficiency. Other consumers might be really focused on no GMOs [genetically modified organisms], or no adverse chemicals. Other consumers look to combine those kinds of issues in some way.”

And oftentimes, the same confusion exists on the side of the manufacturers, says Case. “Manufactures understand these things slightly differently. So you have a group that only understands things kind of partially, communicating with another group that only understands things partially. So there are huge opportunities for miscommunication.”

The result is what some call “‘the power of eco-babble,' with a bunch of people speaking past each other, just generating additional confusion,” says Case.

And that’s why validation and sustainability standards are essential. “Because once you have things like environmental standards and verification protocols that provide clarity in the space, then you can actually have effective communication.”

The ECOLOGO label, which initially was part of Terrachoice prior to 2010, is an example of the expansive breadth of UL Environment’s focus. Case describes it as a “multi-attribute environmental standard” that is able to address needs across multiple industries, from building and construction to electronics.

The program also offers validation of recycled, reclaimed or rapidly renewable materials, which all point toward their ability to redirect materials or products from the landfill.

And perhaps one of UL Environment’s more surprising coups recently is its Zero Waste validation, which backs up businesses that attain 80 percent or more diversion from the landfill. It takes considerable effort for a company to reach that marker.

“We have a roofing materials company that has actually managed to get a close to zero-waste claim,” Case explains. “And then we have a tire company, a manufacturing facility that has managed to do that as well. So it is interesting to see the companies and fascinating how hard they have to work to get there.”

And like many of UL Environment’s validation programs, it’s proof that sustainability matters both to customers and to those who strive so hard to ensure their mark counts for the next generation.

Image courtesy of UL Environment