Support for California’s Climate Disclosure Rules Remains Strong Despite Push for Delay

Gavin Newsom, governor of California, speaking about the state's efforts to cut methane emission at the 2022 Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. (Image: California Governor/Flickr)

California Governor Gavin Newsom proposed a two-year delay on Senate Bills (SB) 253 and 261. The move comes in spite of widespread support for the initiatives. The fate of the climate risk disclosure bills now rests with the state’s legislature. The governing body has until the end of the month to decide whether they will be enacted on schedule.

SB 253 requires companies doing business in California with a total revenue above $1 billion to report the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their direct operations (Scope 1) and their purchased energy (Scope 2) beginning in 2026 and the emissions produced across their value chain (Scope 3) the following year. The revenue threshold for SB 261 — which requires companies to report on climate-related financial risks — is half that amount, at $500 million. If Governor Newsom’s proposal is passed, neither will be implemented until 2028.

“We're experiencing climate change right now. We've got wildfires, we've got flooding, and we need to take care of California and its residents,” Catherine Atkin, director and co-founder of the climate data initiative Carbon Accountable, told TriplePundit. “The only way to do that is to address the broader greenhouse gas emissions environment, and this data will support California protecting its citizens.”

An unnecessary delay

Atkin, who collaborated with bill author and California State Senator Scott Wiener to develop the framework for SB 253, said the proposed delay is unnecessary. To demonstrate this, Carbon Accountable compiled a report, which Atkin was the lead author of, detailing why the bill needs to be put into practice along its original timeline and how to do so. Additionally, a coalition of policy and action organizations joined forces with Carbon Accountable to request the passage of SB 219, which makes technical amendments to ease the bill’s implementation and gives the California Air Resources Board (CARB) an additional six months to complete rulemaking without delaying the reporting requirements.

“There really is no reason for the delay. Both bills have timelines that are attainable,” Dave Jones, director of the Climate Risk Initiative at the University of California Berkeley’s Center for Law and the former insurance commissioner of California, told 3p. “There’s some regulatory work that [CARB] will have to do, but it’s very minimal because both bills rely on well-established international standards for greenhouse gas emissions reporting.”

In addition to the internationally accepted protocols for Scopes 1, 2 and 3, Jones explained that the climate risk and financial disclosures required by SB 261 are based on a framework put in place in 2017 that’s already used by approximately 80 percent of the 1,000 largest publicly-traded companies in the United States.

Business support for California’s climate disclosure bills

“We were really heartened by the business support that built over time, and I think we've really sort of hit an inflection point,” Atkin said of the progress made over the course of passing the legislation. “We saw a lot of things shifting, and I think some of those were leading companies recognizing that they needed to be stewards for the broader business community as well.”

The California Chamber of Commerce is in favor of the proposed delay, along with other changes to SB 253, many of which are addressed by SB 219. But leading companies still support the reporting requirements, Atkin said. The same trend is noticeable globally, which is encouraging despite the pushback from business lobbies, she said.

“There was widespread business and financial institution support for both bills,” Jones said. “And those businesses that supported the bills are opposing the delay.”

Uniform reporting standards garner support and make California a leader

“What companies said to Senator Wiener, and what I heard during this process was, ‘What we don't want is … a special flavor of California ice cream,’” Atkin said. “These largest companies, as you know, are subject to other reporting regimes globally, as well. Many of them will be subject to [the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive], either now or in the future in the European Union. They may be voluntarily reporting in other jurisdictions, or be subject to [the International Sustainability Standards Board] as that gets adopted by countries. So really, what we heard from them was … ‘We want to have confidence and security in knowing that the rules are going to be the same.’”

Using the standard greenhouse gas reporting protocol was therefore imperative. And with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission delaying its climate disclosure rules — which are currently tied up in court — California’s are more important than ever. Atkin is hopeful they’ll go into effect in 2026 as originally proposed. Despite Governor Newsom’s push for the bills’ delay, his work championing low carbon fuel standards, cap and trade systems, and standing up to the oil and gas industry are examples of how the state is a pioneer in the fight against climate change, Atkin said.

“This is just another amazing demonstration of California's global leadership,” she said. “The world is watching California right now, so we need to step up to the plate and deliver on this promise for the benefit of Californians but also the rest of the country and the world.”

Delaying SB 253 and 261 would be a huge setback for the state’s leadership in the climate space and the commencement of emissions and risk reporting, Jones said.

Sticking to the original timeline is good for business

All too often, progress on climate regulations seems to be followed by government backtracking and an overall failure to meet targets. Fortunately, the public can make a difference by paying attention and holding government and business leaders accountable. Atkin credits the public with seeing through commitments and promises that don’t result in real change, specifically related to greenwashing.

“It's critically important that the public, which is paying attention to these issues, but also businesses and advocacy organizations that are concerned about the fact that the planet is literally burning, continue to support efforts in a timely and responsible way to address these issues,” Jones said. “Sadly, it is the case that when important laws like these get passed, it's not necessarily the end of the story. So it requires a continued engagement and vigilance.”

SB 253 and 261 are about transparency. Neither will require businesses to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions or climate-associated risks, Atkin said. But they will help the economy transition and grow.

“We want companies to do well, and this data is going to help them,” she said. “That, to me, is kind of the sweet spot. When we have transparency and accountability, but with an expectation that we're going to build a strong economy through this effort.”

For companies and financial institutions to transition their activities and investments, they’ll need to start by measuring and reporting their greenhouse gas emissions and climate risks, Jones said. That information is also important for the public, policymakers and financial regulators.

“Fundamentally, this is about creating a level playing field so that companies and financial institutions are both identifying and disclosing what their contribution is to climate change, as well as what risks they face from climate change,” he said. “You can't manage what you don't measure, right?”

Fair Trade Avocados Are Growing Rural Economies in Mexico

Avocado pickers harvesting Hass avocados in Michoacán, Mexico.

The global demand for avocados has surged in recent years, transforming this once-regional fruit into an international sensation. While the booming market brings economic opportunities, it also poses obstacles for farmers and communities striving to grow the market in a sustainable and equitable way.

Amidst these challenges, Fair Trade certification is a beneficial program with a mission to foster sustainable development, economic stability and social equity. For Carlos Genel, an economist and second-generation avocado grower in Michoacán, Mexico, becoming a Fair Trade organization was a win for his community.

How Fair Trade works

Fair Trade ensures farmers receive a guaranteed minimum price for their avocados, acting as a safety net against market fluctuations. This stability allows farmers to plan for the future, invest in their farms and provide for their families. Additionally, Fair Trade premiums — extra funds paid on top of the selling price — must be invested back into the community, financing projects like education, healthcare and infrastructure improvements.

“The extra money goes to our workers to improve their lives, and the workers manage and administer the money from the premium,” Genel said. “The program educates them because they learn how a company is managed and how to manage money.”

Even before joining the Fair Trade network, Genel was passionate about sustainable rural economic development. “Joining Fair Trade just formalized the way we liked to work,” he told TriplePundit. “We are part of a huge network of people who value the things that we value, like respecting people and the environment, caring for each member of our team, and thinking about the long term in everything we do.”

Fair Trade certification empowers farmers and workers by promoting democratic decision-making processes. Cooperatives and associations formed under Fair Trade principles give farmers a collective voice, allowing them to negotiate better terms, share knowledge and support each other.

Genel employs between 60 and 70 farmworkers, who used their Fair Trade premiums to launch programs that improve access to food, healthcare and education in their communities. For example, they developed a school for their families and neighbors, with classes for elementary and middle school children, as well as adults. The farm also invests in a local university, Universidad Latina de América, which provides high school, undergraduate, postgraduate and professional certification educational pathways.

“I am the third generation in my family to invest in this university,” Genel reflected. “I feel very proud of that. It is ranked in the top 50 universities in Mexico.”

The workers on Genel’s farm also invested in programs to improve community health and nutrition. Their Fair Trade premiums provide a large basket of groceries to every employee’s family each month, and workers regularly organize health-promoting campaigns such as local testing and educational workshops.

“Recently, the workers paid for an eye doctor to test all of their children’s vision,” Genel explained. “They collaborate with other organizations for other health initiatives, too.”

Social gains grow market opportunities

Fair Trade certification offers transparency and traceability to conscious consumers, assuring them that their purchases support ethical practices. For farmers, it opens access to markets that prioritize ethical sourcing and are willing to pay a premium for it.

Implementing sustainable and socially responsible farming practices has long-term benefits, including the creation of a more resilient agricultural system. However, sustainability and social responsibility are also growing market opportunities for Genel in the short term.

“The certifications I hold, including Fair Trade, have an economic benefit,” he said. “I can export directly to the U.S. without going through an intermediary, which saves money. I am starting to develop partnerships with American companies like Costco and Whole Foods.”

Genel sees other producers in Mexico beginning to realize the economic benefits of participating in programs like Fair Trade.

“There is a generational change happening now. New generations are coming into the family business, and they have a different mindset and perspective,” he observed. "They see the benefits of Fair Trade and other agricultural certifications. Many of these farmers are environmentally friendly and have a great social impact, but they don’t know that there are certifications they can leverage. It is important to educate other farmers and workers about the existence and benefits of these programs.”

Sowing seeds for the future

Genel is working hard to expand his outreach efforts. “We have a social responsibility program at the company as well as many sustainability initiatives and practices that we have put into place,” he said. “We have been working with growers in Chihuahua on developing better irrigation methods for very dry land. In Michoacán, we have implemented these methods, too, not because the land is dry but because it saves water and allows for more efficient water management.”

Even while expanding his educational efforts to other growing communities, Genel remains focused on preserving the ecosystem where his farm and family thrive. “We have a big forest on our land, full of flora and fauna. There are local, native species of animals and plants,” he told us.

He knows the success of his farm is largely tied to the ecosystem services and positive environmental impacts that forests provide. “We have developed an initiative to help maintain the health of the forests,” he explained. “It is part of our business strategy to take good care of our ecosystems and communities.”

This article series is sponsored by the Avocado Institute of Mexico and produced by the TriplePundit editorial team.

Images courtesy of the Avocado Institute of Mexico

Could AI-Bred Microbes Help Save Our Plastic-Choked Oceans?

(Image: Brian Yurasits/Unsplash)

Thanks to our addiction to easy-to-use and dispose of single-use plastic, the world’s seas are a mess. If we are to save them — and the marine life in them — we need a strategy to remove the plastic plaguing the seas and figure out ways to keep these essential waters clean.

New advances in computational biology and microbiome research could help with the development of those strategies and solutions, especially the use of microbes that actually eat plastic. Using artificial intelligence (AI) powered discovery and optimization technologies along with genetic manipulation techniques, scientists have made a great deal of progress in identifying and developing such microbes.

Mass production of these microbes could, for the first time, enable humanity to get ahead in the race to prevent a total plastic takeover of the environment, both on the sea and land. While a great deal of work still needs to be done, researchers believe these microbes could hold the key to a cleaner and healthier environment — and better human health.

Marine plastic pollution has reached epidemic proportions. A UNESCO report contains frightening statistics: There are about 50 to 75 trillion pieces of plastic and microplastics in the ocean, which is growing by 8 to10 million metric tons yearly. Plastic waste now makes up 80 percent of all marine pollution, and within three decades, the sheer mass of ocean-going plastic will exceed the weight of all fish in the sea, according to the agency.

Plastic can take as long as 1,000 years to decompose totally. In the meantime, it simply deteriorates into smaller pieces of microplastic, often consumed by fish, which are eventually eaten by humans and other animals. While the long-term consequences of this plastic consumption have yet to be studied, they are unlikely to be good. In any event, researchers say that the chemicals associated with microplastics are likely to lead to numerous serious health issues such as endocrine disruption, weight gain, insulin resistance, decreased reproductive health and cancer.

However, recent evidence has discovered some microbes — tiny living organisms — can essentially degrade certain plastics, signaling new hope for our polluted oceans. Take for instance, a chance discovery by a Japanese research team of a microbe “happily chewing through plastic bottles.” Another study collated a large database of additional microorganisms identified as capable of degrading plastics.

Earlier research initially showed that microbes could reduce plastic pollution, and more recent studies show that microbes are evolving to biodegrade plastic. A Swedish team discovered 30,000 enzymes — proteins produced by microbes that build up and break down substances — that could degrade over ten types of plastic. While these enzymes can reduce pollution on land and sea, they are especially suited to digesting plastic in the ocean.

Unlike on land, the number of these plastic-digesting enzymes increases with the depth of the water and as the presence of plastic pollution increases. This could indicate that the enzymes adjust their abilities based on the environment and amount of plastic present. It’s unclear how this evolution is taking place or through what mechanism specific microbes and genes respond to particular types of plastic, but it is a growing area of research.

Many questions remain. A large-scale study of how microbes interact with plastic has yet to occur. Much more research is needed to develop an effective, large-scale solution to microbe-based plastic decomposition. That is likely to require genetic manipulation of microbes to whet their “appetite” for different kinds of plastic, as well as developing methods to produce them in large amounts.

And while microbes can effectively break down certain kinds of plastic, they can take a very long time to do so, given their small size. Many microbes would be needed to make a dent in large pollution concentrations, such as the Great Pacific Plastic Patch.

Most of the microbes discovered operate on two particular kinds of plastic: PET and PE plastics. Often used to make bottles and bags, scientists say these are “relatively easy” types of plastic to decompose. Developing microbes to decompose other types of plastics will be a more significant challenge, though progress is being made.

Meanwhile, the decomposition of plastics could lead to other problems, such as the large-scale release of carbon dioxide, which has adverse effects on the roots of aquatic plants and abnormalities in their production of sugars and proteins and their ability to absorb nutrients.

The solution to these issues could also lie in the genetic manipulation of enzymes to increase their plastic-eating efficiency and limit or eliminate the harmful effects of releasing excess carbon dioxide or other gasses. It was also an accidental discovery that led scientists along this path. British scientists used X-rays and other tweaks to improve the effectiveness of the original plastic-eating enzymes discovered by the Japanese team, developing a new enzyme that works much more quickly and efficiently. It can also be produced in quantities, although it is primarily restricted to eating PET-type plastic.

Meanwhile, researchers at North Carolina State University developed another genetically modified microbe that breaks down PET plastic quickly and can thrive in salt-water environments, which is a challenge in other plastic-eating microbe projects.

It is clear that recent scientific advances are enhancing the ability of microbes to consume plastics. But the potential applications for waste-eating microbes go far beyond plastics. Research is increasingly shedding light on the potential to use bacteria to address other pollutants like industrial and explosive waste. Efforts should be made to address these issues simultaneously as the options increase for using biology and living organisms to clean up the environment.

While much more work needs to be done, it appears that microbes developed or tweaked with the help of AI and computational biology can help us in the battle against a wide range of pollutants, especially plastic in the oceans. And we need that help desperately.

Corporate Climate Targets Are a Mess. Could Tracking 'Spheres of Influence' Help?

(Image: Manny/Pexels)

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist's weekly newsletter here.

In order to avoid the worst impacts of global warming, scientists agree that the world needs to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by midcentury. How to get there is a more contentious question.

So far, the dominant strategy has been for companies, governments, and other institutions to set their own emissions reduction targets. The idea is that if everyone aims for net-zero by 2050 and comes reasonably close to achieving it, the world will be spared a climate nightmare.

This strategy has only worked to a limited extent — especially in the private sector. More than half of the world’s 2,000 largest publicly listed companies don’t even have a formal net-zero goal, and only 4 percent of those that do meet a United Nations initiative’s baseline criteria for reliability. Companies often rely on questionable accounting or otherwise exaggerate their progress toward climate targets, despite the emergence of several independent standard-setting bodies and verification schemes.

Researchers at the University of Oxford and the Exponential Roadmap Initiative, a Swedish organization that advocates for corporate emissions reductions, are now calling for a different approach — one that can effect change on a more systemic level. In a research paper published last week in the journal Carbon Management, they argue for an additional corporate climate reporting system that incentivizes other forms of action, like lobbying for national climate policies and investing in conservation projects.

“We have been leaving a huge amount of impact on the table by failing to encourage or invite companies to be rewarded and compared for their significant efforts beyond their value chain,” said Kaya Axelsson, a research fellow at Oxford University’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment and a co-author of the paper.

She said those rewards could take a number of forms, including interest from consumers or investors, or preferential treatment for government contracts.

Axelsson and her co-authors are by no means the first to criticize existing corporate carbon accounting practices. Over the past several years, academics, think tanks, and even government agencies have suggested ways to boost transparency and make companies’ net-zero pledges easier to compare. Standard-setters themselves have also sought stakeholder feedback to address widely acknowledged problems. Few experts, however, have called for an entirely new set of accounting standards.

Under the researchers’ proposal, companies would set targets and track progress toward three “spheres of influence,” related to categories they call “product power,” “purchasing power,” and “political power.”

This is in contrast to today’s most prevalent climate reporting regime, in which companies tally up the greenhouse gas emissions associated with their own operations, the electricity they buy, and the products they sell to customers — known as Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions, respectively. These scopes are collectively described as a company’s greenhouse gas inventory.

The authors’ first proposed sphere of influence, product power, would consider emissions avoided as a result of a company’s new products or practices, compared to a world in which those products or practices didn’t exist. The authors say this could incentivize companies to decarbonize all of society, rather than simply increase the efficiency of their existing products and supply chains.

This gets at a problem that might be faced by, say, a fast-growing renewable energy company. Under the scope-based standards, the company would be penalized for the greenhouse gas emissions it emits when it manufactures wind turbines. But those turbines might be used to displace another company’s fossil fuel use, providing a societal climate benefit. The renewable energy company should be recognized for this contribution to the greater good, Axelsson said.

The second sphere, political power, would recognize the role companies play in shaping local, national, or international regulations, and incentivize them to advocate for climate action, rather than against it. This reflects the guidance of an expert panel of the United Nations, which said in a 2022 report that corporate actors “must align their external policy and engagement efforts, including membership in trade associations, to the goal of reaching net-zero by 2050.”

The goal wouldn’t necessarily be to quantify the impact of companies’ political lobbying, the paper clarifies, but to acknowledge and reward it: “A company taking significant steps to change a political system constraining climate progress across its sector should arguably be treated preferentially to a company with the same inventory emissions who has chosen not to engage in political processes.”

Perhaps most significantly, the researchers’ third proposed sphere, on purchasing power, would address a divisive question: whether activities to drive down emissions outside a company’s operations and supply chain can somehow count toward that company’s climate targets. Today, many companies say yes — they participate in an unregulated carbon market in which credits representing some amount of sequestered or prevented carbon dioxide can be purchased in order to “offset” a company’s Scope 1, 2, or 3 greenhouse gas emissions. These credits are typically generated by activities like planting trees, investing in renewable energy to replace fossil fuels, or protecting forests that are in danger of being chopped down.

Scientists say this approach is flawed for a number of reasons, including because it implies an inaccurate equivalence between a ton of carbon emitted from the combustion of fossil fuels and a ton of carbon stored in biological systems. Research has shown that the two don’t have an equal and opposite effect on the climate system. Carbon offsets can also give companies an excuse not to reduce their own emissions.

That said, credit-generating activities themselves can actually be helpful; it’s their use as offsets that’s problematic. The purchasing power approach would track companies’ support for these activities separately from their greenhouse gas inventories, giving them an incentive to continue that support without the contentious math associated with offsetting. This is similar to the idea of “contribution claims,” in which companies simply advertise their financial contribution to renewable energy projects, grid resilience, afforestation, and other climate action, without making any claims about the amount of carbon saved.

“Projects which serve to protect nature or enable clean development still play a role, if imperfect, in global mitigation and adaptation efforts,” the paper says. “When a company uses its purchasing power in this way it goes above and beyond another company that has not done so.”

Doreen Stabinsky, a professor of global environmental politics at the College of the Atlantic in Maine who was not involved in the research paper, said the new proposal could address flaws in current climate reporting systems. But she questioned the premise that corporations will be sufficiently motivated to address climate change just because doing so would appeal to consumers and investors.

“I agree that there’s a problem with a myopic focus on inventory emissions, and I agree that you need to have innovative strategies that operate at a system level,” she said. “But I’m critical of thinking that it’s up to individual companies to innovate those system-level strategies.”

She said the researchers’ proposal focuses too much on improvements to the market system and overlooks governments’ responsibility to oversee society-wide decarbonization. “There are things that we’re not going to be able to make happen through these market-based approaches,” she added.

Axelsson told Grist she sees voluntary standards as “a necessary but insufficient tool for corporate climate accountability,” and said they can be a stepping stone to government policies.

“Standards can be a good regulatory sandbox for testing new ways of thinking about concepts holistically,” she added. “If net-zero is at a turning point where we’re asking companies not just about their footprint but also about their impact, we probably need to test that in a voluntary space and then hopefully governments can start seeing that that’s something that they can ask for.”

This article originally appeared in Grist. Grist is a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org.

Harnessing AI for Corporate Sustainability Requires Precautions

(Image: Martin Sanchez/Unsplash)

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to play an integral role in corporate sustainability. However, the massive amount of energy needed to run the technology threatens to overshadow potential advantages. Widespread use is expected to cause a 160 percent surge in data center energy demands by the start of the next decade, undoing previous gains in operating efficiency.

A recent survey from the software company Salesforce and the market research firm YouGov reflects this dilemma, with 81 percent of sustainability professionals agreeing that lowering AI’s carbon footprint is important. At the same time, 58 percent think it can be used to have a net positive impact on the climate crisis.

How are sustainability professionals using AI?

“The top use cases are for improving energy efficiency,” Boris Gamazaychikov, the senior manager of emissions reduction at Salesforce, told TriplePundit. “So things like monitoring energy consumption [and] predicting when energy use is high, carbon emissions modeling, and then ensuring compliance with environmental standards and regulations. Those are kind of the top three.”

Of those using AI in their sustainability programs, 65 percent claim it is transformative. But only 20 percent of the survey’s respondents completely integrated AI into their sustainability programs. Another 29 percent are still testing its use.

Not everyone is convinced that AI will be a boon for sustainability. While approximately half of respondents use AI in their sustainability efforts, the other half do not. Almost 40 percent said they are concerned that it will do more harm than good for their company’s sustainability.

“AI does have this very sort of wide-ranging and potentially extremely beneficial range of uses, but I do not think that we are quite there in terms of the corporate space,” Monica de Bolle, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told 3p. She expressed concern that — while AI can be used to track energy use and other beneficial monitoring activities — it’s all too common for the tech to be used for inane activities, like drafting emails, that save minimal amounts of time and use excessive energy.

Where should the line be drawn on AI?

AI is also used for forecasting and reporting, Gamazaychikov said. “It's great that we have so many [environmental] regulations,” he added. “It's really important. But now there's so much time spent by sustainability professionals filling in forms, basically, and writing the same narrative in a slightly different way to satisfy a slightly differently worded question. So generative AI is really well suited for that.”

Likewise, AI can look at millions of data points and make forecasts in a fraction of the time it would take a human. Still, it’s important for sustainability professionals to be cognizant of the carbon footprint of their AI use versus how effective it is and how much time they save.

“The kind of energy consumption that we're talking about for different types of AI algorithms is equivalent, or higher than, what cryptocurrencies consume in terms of energy,” de Bolle said. Policymakers and grid planners continue to raise concerns about cryptocurrency mining’s energy use and emissions. It’s likely responsible for 0.6 to 2.3 percent of the United States’ electricity consumption, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

That’s a big deal considering 75 percent of knowledge workers use AI in the workplace. And many of them are providing their own tools, which means the full breadth of environmental harm caused by AI use in the office may be unknown.

“I think using AI to help people write emails is definitely a waste,” de Bolle said. “If you're a corporate leader, and you're looking at the uses of AI within your own company, and you're somebody who's environmentally minded, and you care about the impact that your company's having, then you … should be delineating those activities where AI is going to be used and where AI is not going to be used.”

Instead of using it to do basic tasks like draft emails or simple online research, de Bolle said she would rather see AI reserved for things like scientific projects, medical care or energy monitoring, where it can make the kind of difference that justifies its emissions and energy use.

The need for transparency and intentional energy efficiency

Gamazaychikov and de Bolle seem to agree that AI has a transparency problem. Despite, or perhaps because of, its eruption in popularity, users are largely unaware of its environmental consequences.

“It's critical that this sector be regulated,” de Bolle said. “These [AI] companies are very opaque in terms of how they operate. And they're very opaque, in particular, with regard to disclosing how much energy is actually consumed … So there needs to be regulation that says, ‘Look, you need to disclose this information.’ Because otherwise, how can companies that are actually using your product … how can they know the costs and benefits?”

Gamazaychikov would like to see a rating system for AI similar to Energy Star, the federal program that administers the familiar blue star label on products and buildings that meet strict energy efficiency standards. That’s something Salesforce is working on with the AI firm Hugging Face, in hopes of bringing transparency to the industry.

In the meantime, he suggests that companies look at the underlying algorithms when choosing a model to use for sustainability programming. The largest models have trillions of parameters that create the foundation for their decision-making abilities and are dramatically less efficient than smaller language models that use billions of parameters, Gamazaychikov said. The smaller traditional machine learning models are sufficient for the monitoring, predicting and forecasting that corporate sustainability teams do.

“Next it's important to think about the hardware that's actually running these models … There's a lot of efficiency improvements that have been happening with AI hardware, so it's important to be mindful of what's being used to train and then deploy your AI,” Gamazaychikov said. “And then finally, the type of energy that's being used to power these data centers. How much of that is fossil fuel? How much of that is renewable energy? Between somewhere like France, with a very clean grid, and India, with a lot more fossil fuel, you can see a 95 percent carbon emissions difference. [It’s the] same exact workload, but just talking about a different type of energy usage.”

Do the benefits outweigh the harm?

It may sound like a lot for sustainability professionals to consider, but which model they choose will determine the environmental impact of their company’s AI use. After all, the whole point of using the tech in sustainability programming is to enable sustainability — not to solve one efficiency problem by creating another.

But for AI to have a net positive impact, companies need to limit its use to where it can make a real difference. “I think you have to use AI responsibly,” de Bolle said. “And using AI responsibly means: Is it really helping to get to whatever result you want to get to? Or are you just cutting down three minutes of a person's time by using AI to write an email?”

Overall, AI appears to have the potential to make a huge difference in corporate sustainability if it’s used responsibly. “We're at a really critical inflection point,” Gamazaychikov said. “AI innovation has been picking up dramatically, so we're at this point where we are seeing a potential future where AI could exacerbate climate change if precautions aren't taken.”

Two Years Later: What's the Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act?

People gather on the South Lawn of the White House to hear President Joe Biden speak at a celebration event for the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act on September 3, 2022. (Image: Official White House Photo by Katie Ricks via Wikimedia Commons)

The Inflation Reduction Act marked its second anniversary last week. Much of the attention focused on the size and number of new, mega-scale renewable energy projects it supported. That's only the beginning, as millions of households, small businesses and other stakeholders begin to explore new tax credit opportunities for investing in small-scale renewable energy and energy-efficiency projects.

The impact of the Inflation Reduction Act, two years later

A recent analysis from the U.S. Treasury Department gives insight into how individual households are leveraging the tax credits available under the Inflation Reduction Act. “New data from the Internal Revenue Service show that more than 3.4 million American families have already claimed more than $8 billion in residential clean energy and home energy-efficiency credits against their 2023 federal income taxes,” the Treasury Department reported earlier this month.

The bulk of the total consisted of $6 billion in tax credits claimed by 1.2 million families for renewable energy projects including solar panels, solar water heaters and batteries for home energy storage. Another 2.3 million families claimed the remaining $2 billion for home energy-efficiency improvements like heat pumps and insulation, for an average of $880 per family.

The Treasury Department projects the final figures for the 2023 tax season will be even higher, as late and extended returns are still being processed.

Residential investments in clean energy and energy efficiency translate into significant savings on utility bills, helping to insulate households from volatile energy costs, the analysis noted. That price protection can play an important role in mitigating recessions linked to energy price shocks, which can have a positive ripple effect on small businesses and other local stakeholders.

In addition, household savings on utility bills can free up more money to circulate in the local economy. A recent survey commissioned by the online marketplace Faire takes note of strong consumer sentiment in favor of supporting local shops and businesses as an important quality-of-life element in their communities.

Above all, the analysis emphasizes that small-scale energy investments under the Inflation Reduction Act will add up to a significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., and on the economy as well. If every household switched to heat pumps, for example, total U.S. carbon dioxide emissions would fall by up to 9 percent annually, leading to follow-on economic benefits between $84 billion and $150 billion each year, according to the U.S. EPA .

A helping hand for accessing information about tax credits

Individuals and small businesses typically don't have the same tax attorneys and accountants as large-scale energy developers, but resources are available to help smaller energy buyers find out about new opportunities presented by the Inflation Reduction Act.

Among them is the new Climate Hub launched by the office of Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) last week. Designed to ensure information about grants and tax credits reaches small businesses and other small energy consumers, the Climate Hub covers provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act as well as the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (also known as the bipartisan infrastructure law).

"Together, these two laws have created the largest and most significant climate and clean energy investments in history, putting the United States on a path to address the climate crisis, repair historic harms to disadvantaged communities, create good-paying union jobs in the clean energy economy, and work towards a Green New Deal future,” Markey said in a statement.

The Climate Hub collects all of the relevant information about available tax credits in one place, including how-to instructions, webinars and resource guides developed by Markey's office as well as the White House, federal agencies, and non-governmental organizations.

Anyone can use the Climate Hub website, but Markey draws particular attention to energy consumers who don’t have the knowledge and resources available to large-scale investors. That includes cities, towns, Indigenous Tribes and communities impacted by environmental injustice, along with schools, labor organizations and individuals.

One particularly valuable message from the Climate Hub is a reminder that the provisions of these two laws are not yet fully implemented. Tax credits available through the Inflation Reduction Act, for example, will continue in effect until 2032 or until the U.S. achieves a 25 percent reduction in carbon emissions from electricity generation.

Business owners, managers and other stakeholders can stay updated on new developments by checking into the Climate Hub website regularly, getting in touch with their representatives in the House or Senate, or exploring opportunities to enroll in the Green Power Partners program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Beyond energy tax credits

In addition to the impact on carbon emissions, the Inflation Reduction Act has also fostered an important link between climate action and benefits to small businesses, including rural businesses.

Celebrating the two-year anniversary of the law last week, Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack took note of lower energy costs, job creation, and protection from wildfire and extreme heat risks across rural U.S. communities. “The Inflation Reduction Act makes a once-in-a-generation investment that supports rural communities and their infrastructure needs, while adapting to the climate crisis and creating better health outcomes,” he said in a statement.

As the saying goes, money talks. Although the Inflation Reduction Act passed into law along strictly partisan political lines, the economic benefits have been distributed across the U.S. regardless of party affiliation, and projections indicate that U.S. communities and businesses will continue to benefit for many years to come.

The World Bank’s Accountability System Must Reform: Experts Map Out How

The World Bank Group headquarters in Washington, D.C. (Image: ajay_suresh/Wikimedia Commons)

The World Bank marked its 80th anniversary last month, and while a lot has changed in the past eight decades, one aspect of the institution remains the same: its resistance to being held accountable. Past and current World Bank-funded projects displaced people, destroyed livelihoods, polluted water, harmed biodiversity and exacerbated sexual exploitation, among other harms. Even though harm to people and the planet is a known outcome of some of its projects, the World Bank does not routinely acknowledge or redress it.

Instead, it falls on brave human rights and environmental defenders to raise the alarm, demand justice and convince the bank to be accountable. That shouldn’t be the norm. And right now, there is an opportunity to finally change course. The World Bank’s board can empower the institution’s accountability mechanism to identify and redress environmental and human rights harm.

The World Bank has an institutional channel — albeit a flawed one — for hearing from people harmed by its projects, which is called the independent accountability mechanism. Created by its board in 1993 in response to people demanding accountability, the World Bank’s Inspection Panel investigates allegations of non-compliance with its own environmental and social policies.

The panel’s creation was a groundbreaking development that other development finance institutions have since replicated. And over the past 31 years, the Inspection Panel published multiple investigation reports confirming the concerns raised by communities globally.

Despite its successes and incremental changes made to the panel over the years — including the creation of a mediated dispute resolution process for impacted communities and implementing agencies — the World Bank’s accountability mechanism was never given the mandate to fully hold the organization responsible for the impacts of its projects or deliver remedies to address harm. The mandate is woefully behind its peers at other development finance institutions. That’s something the bank should be ashamed of, because it means that the organization knows there are better ways to ensure projects do not harm the environment or infringe upon human rights yet is unwilling to act.

The ways in which the World Bank has hindered its own accountability mechanism are myriad: The panel needs the board’s approval before it can begin an investigation, communities filing cases are not permitted the counsel of their choosing, communities have to consider a dialogue with the Dispute Resolution Service before an investigation, and the panel can’t even recommend remedial actions or monitor how the bank responds to its investigation findings, among others.

The shortcomings of the World Bank’s accountability mechanism are not theoretical. They limit communities’ access to justice and undermine the credibility of the bank. For example, the panel could not monitor the actions taken by the bank after an investigation confirmed harm caused by an energy project in Nepal. Bank management was able to misrepresent the level of communities’ consent to ongoing project construction and the nature of government intimidation and violence toward the communities.

We demand that this changes now. The World Bank’s accountability mechanism should be best-in-class and truly have the mandate to underpin the bank’s ambitions to become bigger and better.

Last month, a team of experts published a Draft Report and Recommendations for the World Bank’s board based on a review of the effectiveness of the bank’s accountability mechanism and asked for the public’s feedback. The terms of that review were limited and imperfect, but the report recommends multiple important improvements to the World Bank’s accountability mechanism. Civil society organizations provided detailed feedback based on our experience advocating alongside local communities demanding justice. Several key improvements are needed for the World Bank’s accountability infrastructure to truly be effective.

The structure of the accountability process must facilitate justice. The structure of the accountability mechanism hinders its effectiveness and is confusing to affected communities trying to understand what to expect from the case process. As discussed in the review report, a near-term solution is to separate the Inspection Panel from the Dispute Resolution Service and ensure that both have the necessary resources to do their work.

The entire accountability process should be accessible to impacted communities. Barriers to accessing the accountability process should be removed, including prohibiting individuals from raising complaints and restrictions on communities’ choice of representation. Importantly, communities must have the ability to choose how they want their concerns addressed, whether through a compliance investigation, a dispute resolution process or both.

Findings of noncompliance should always be addressed. The World Bank should be obligated to rectify and remediate harm related to any non-compliance the Inspection Panel finds during an investigation. To facilitate that, the panel should be given the power to recommend ways for the bank to course-correct. And the panel should always monitor the implementation of the bank’s remedial efforts to ensure they are actually accomplished.

The outcomes of the accountability mechanism’s dispute resolution processes should be published and transparently monitored. Reaching an agreement to address community grievances is just one step in ensuring justice. Because of the stark power imbalances between the parties, the bank’s borrowers can all too easily back out of commitments without transparency and effective monitoring of the agreement’s implementation. The accountability mechanism should publish the specific outcomes of its mediation process so that expectations are clear. It should then monitor and report publicly on implementation.

The World Bank knows its projects cause serious human rights and environmental harms that undermine its mission. It should want to hear about mistakes and rectify them to ensure its financing meets the mark and the bank can be trusted by the people it claims to serve. A critical way to do that is by making sure the people suffering have a fair and accessible way to raise issues and have harm addressed. For that to be true, the World Bank’s Inspection Panel and overarching accountability mechanism must be empowered to truly hold the institution to account. An 80th anniversary seems as good a time as any to chart a new course of accountability.

New Credit System Encourages Businesses to Halt and Reverse Biodiversity Loss

La Fortuna Waterfall in Costa Rica, a country home to about 5 percent of the world’s biodiversity. (Image: Etienne Delorieux/Unsplash)

Biodiversity loss is recognized as the third largest global risk over the next decade. As awareness grows, businesses are increasingly setting biodiversity-related targets due to reputational risks, stakeholder expectations, operational and financial risks, and dependency on ecosystem services like pollination and clean water. But integrating biodiversity in responsible investment and reporting is challenging, as it’s difficult to measure an organization’s impact. Businesses attempting to take action on biodiversity encounter obstacles like a lack of understanding of the impacts and measuring methods and difficulty incorporating the management of shared resources into standard business practices.

To address these challenges, and biodiversity loss at large, researchers developed a credit metric with support from the United Kingdom Natural Environment Research Council. The Biodiversity Impact Credits (BICs) metric computes changes in the probability of a species long-term survival related to businesses' actions. This metric assesses species extinction risk and is based on the changes in global species population patterns caused by an organization — with adjustments for species nearing extinction.

The researchers propose that this metric aligns with the global biodiversity goals set in place to reduce extinction risk at the 2022 United Nations climate change conference. It could also be adopted in biodiversity policies and financial reporting. The membership organization Botanic Gardens Conservation International manages the credits.

Applying Biodiversity Impact Credits

The BIC metric helps people understand how species populations are changing due to business activities, said Axel Rossberg, lead researcher of the study. Companies can use this credit metric by measuring their intentional and unintentional impact.

For example, a business emitting harmful chemicals that reduce the population of a local species would earn them negative credits but taking action to prevent biodiversity decline would earn positive credits. Businesses calculate their result and effect on biodiversity by adding together all negative and positive impacts, Rossberg told TriplePundit. These credits are based on a business’s current state and not on its future restoration plans, projected improvements, or risks and uncertainties of future restoration plans with other organizations.

Benefits beyond business

There is a global funding shortfall for biodiversity conservation with an estimated $700 to $900 billion needed to restore and preserve global biodiversity. Biodiversity credits create the potential to boost private funding in biodiversity and conservation. And these credits bring benefits to businesses, such as market differentiation and being up to date with regulations and consumer preferences and interests.

While the prevailing narrative suggests businesses should protect biodiversity because they depend on the ecosystem, this view is only partially correct, Rossberg said. Species extinction is a weak argument because the species close to extinction do not significantly contribute to ecosystems. The real benefit for businesses lies in contributing to the common good, he said.

“In different places, different people in different cultures value biodiversity in different ways," Rossberg said. People derive unique benefits from ecosystems, so the conservation of species is for the benefit of future generations and the opportunities it may bring. We currently cannot predict the benefits future generations might seek from ecosystems, so preserving species is critical, he said. "If it's lost, it's the most difficult to get back."

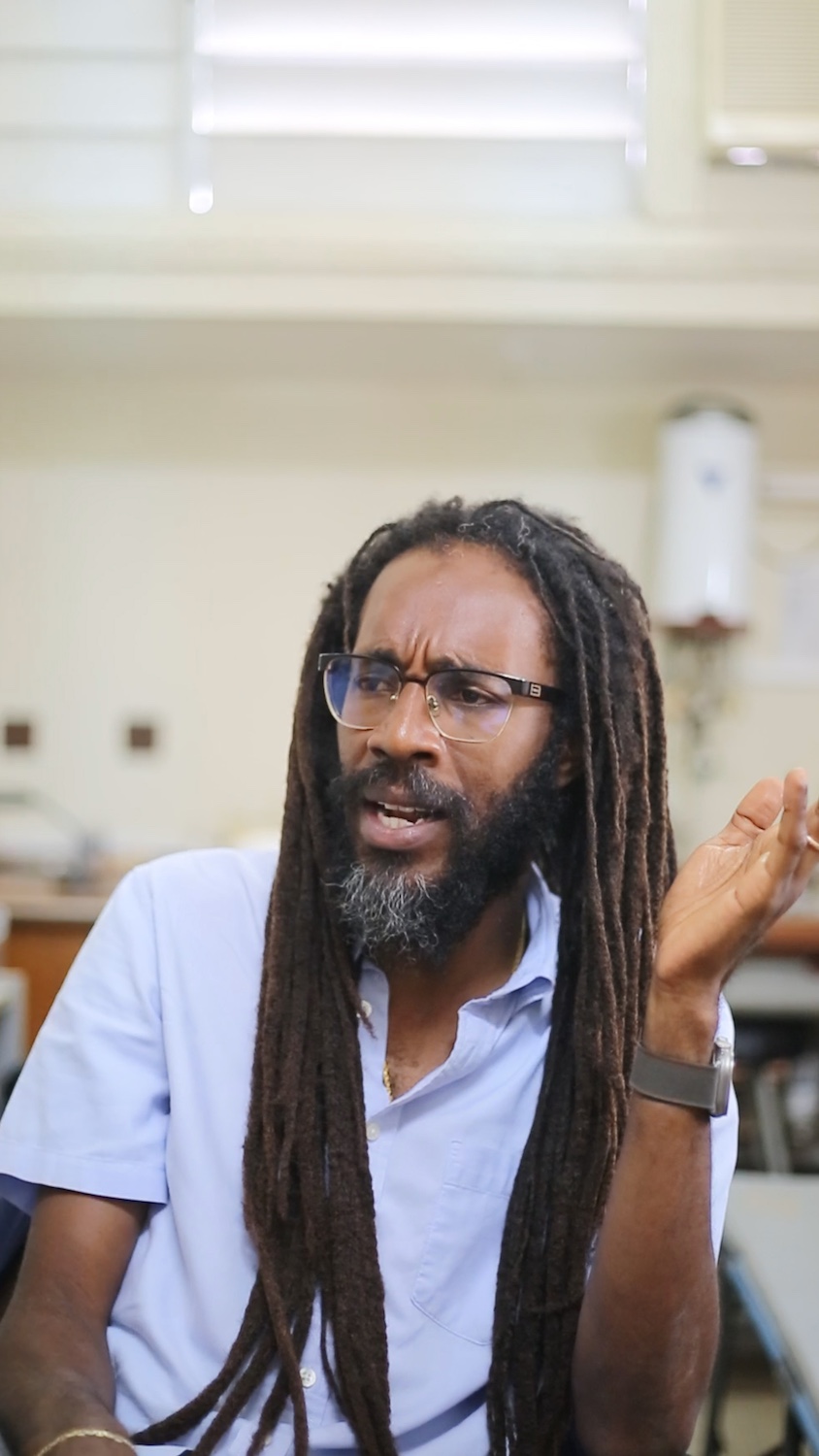

Sustainable Takeaways from the Rastafarian Ital Diet

Local fruit for sale in Falmouth, Jamaica. (Image: Alison Toon/Adobe Stock)

Bob Marley is widely known for his music, his Rastafari faith and even some pro-environment sentiments. After all, climate change was already an issue in the seventies during the height of his career. What many people may not know is at the heart of Marley’s faith sat strong environment-friendly principles that still persist among the Rastafarians of Jamaica today.

An essential principle within their beliefs is the concept of Ital. The Ital diet is similar and often even conflated with the vegan diet, but it is not the same. So what does Ital mean? It can be considered differently by different people within the Rastafari faith.

“My interpretation of it is ‘natural,’” said Kareece Lawrence, a wellness event producer at the Rastafari Indigenous Village in Montego Bay, Jamaica. “One of the special things about Rastafari is the language. We’ve chosen to use words with more feeling and positive meaning. Which is how you get words like ‘I&I’ instead of ‘we’ and that is how you get words like ‘Ital’ instead of ‘natural.’”

Though there are different factions with different beliefs and lifestyle practices within Rastafari, there is some consistency with the Ital diet, Lawrence said. “Not having processed foods, animals and eating from the earth — preferably your own garden or a farmer you know and trust.”

The Ital diet is what’s known as a sustainable food system. A closed-looped way of eating that

allows the food source and the environment to replenish. Food system transformation is a great way to address health and the environment at once, according to research published in the Journal of Cleaner Production.

Food systems are estimated to be responsible for a third of human-caused greenhouse emissions. But it’s not just the emissions that contribute to climate change, it’s also the growing practices, said Machel Emanuel, life sciences lecturer and botanist at the University of the West Indies. Pesticide and fertilizer runoff can be absorbed deep into the earth, blighting the land, or washed into waterways, significantly disrupting the ecosystem there. Pesticides can also pose health risks to humans, particularly people with high levels of exposure like agricultural workers.

While it may not be possible to completely overturn the food processing industry in one fell

swoop, some key takeaways from the Rastafarian Ital diet could help inform and inspire a healthy transition.

Leonard Howell, who is widely regarded as the first Rastafarian, established a 500-acre commune in the hills of St Catherine. It was fully self-sufficient with over 4000 members eating and living off the land. This is where the germ of the Ital concept of a three-pronged approach to food system transformation began to thrive. For Howell, it was about creating economic independence by eating what they grew, but it was just as much about the health of the people and the environment that nourished them.

The principle of eating what you grow is a great place to start. You don’t need a 500-acre commune. A simple backyard garden or planters on a balcony would do.

Limiting the consumption of ultra-processed foods is another key principle that has application in any household. These foods have preservatives, flavorings, sugars and other substances added to them to enhance flavor and lengthen shelf life. Looking into organic alternatives for some of your favorite ultra-processed foods is an excellent first step. Developing a relationship with a farmer’s market in your area could also be a good way to support organic agriculture and fill in areas where your backyard garden may fall short. Support for these markets is already growing, Emanuel said.

“We see the change taking place,” Emanuel said. “People are becoming more conscious of where the food comes from, who is actually growing it, and what sort of inputs are being used. So you’ll see a lot of farmer’s markets being set up around the country. We see consumers are willing to patronize agricultural products where they are closer to the people growing them and are able to have a certain amount of input in the way things are done.”

But food processing isn’t necessarily the enemy. Not all processed foods are ultra-processed, and there are ways to do it without risking the viability of the environment. A project from the Norway-based food research institute Nofima, for example, tested new technology with the potential to replace autoclaves — a machine used to ensure food safety and extend shelf life that requires a lot of water and energy. These new sustainable ways to process food are slowly making their way into the industry.

More Than Socks: How a Knit Manufacturer is Changing Lives with Second Chances

FutureStitch makes socks and other knits for brands like Crocs. (Image: Leeor Wild for Crocs)

Roughly three out of four people remain unemployed a year after they are released from prison. Long-term, that unemployment rate remains at about 27 percent — exponentially higher than the rate for individuals who have never been incarcerated. People who were formerly incarcerated also face substantially higher rates of homelessness and economic and social inequality. Unsurprisingly, unemployment, homelessness and a lack of access to resources are among the factors linked to recidivism.

By and large, employers remain biased against hiring justice-impacted individuals. Sustainable knits manufacturer FutureStitch wants to change that. The company focuses on hiring formerly incarcerated individuals and reducing recidivism among employees for its U.S. factories, a practice known as second chance hiring. FutureStitch makes socks and other knits for brands like Lululemon, Crocs and New Balance. It also partners with the NBA and the MLB.

“We feel like the biggest proof point that we could create in business was around this social cause, which we think is a plague in America.” Taylor Shupe, CEO of FutureStitch, told TriplePundit.

Offering the training and support needed to thrive, not just survive

Shupe, who was involved with the criminal justice reform nonprofit the Innocence Project, was inspired to bring manufacturing back to the U.S. and, in the process, create a program that would prove there is a better way forward than the revolving door of the criminal justice system. The resulting program is called SecondStitch. It offers justice-impacted individuals employment, training and development, while also connecting them with the support and community resources they need to successfully reintegrate.

It begins with foundational skills — such as personal finance and computer competency — and builds up to more specialized training, Shupe said. The goal is to create an entrepreneurial mindset and foster growth. Classes are offered in things like marketing, finance and other in-demand subjects, so employees can choose from a wide range of skills to benefit their future.

That education and training empowers graduates to move up in the company. “My head of HR is justice impacted, and one of my controllers is justice impacted,” he said. “So it's not just production work. It's actually like, let's build the right skill sets.”

In other words, it’s not just about giving formerly incarcerated people the bare minimum in employment. It’s about providing a foundation for them to build their lives on. That’s an important distinction considering that being limited to low wage jobs is another contributing factor of recidivism.

“It’s equally as important to get them into position where they can make enough money to support themselves and their family, buy a house,” Shupe said. “Things that they thought that they wouldn't be able to do, ever.”

A working environment that fosters retention to reduce recidivism

“Most people that get out of the system are not online,” he said, which can make recruitment difficult. “Where we've found opportunities, [is] working with charities that help ex-incarcerated individuals or also homeless people.”

In addition to being justice impacted, more than half of FutureStitch’s employees are previously unhoused, he said. Although not all of FutureStitch’s employees have been impacted by the legal system, 71 percent were, according to the company. The employees who were formerly incarcerated have a higher retention rate than the workers who were not, Shupe said. Whereas the overall retention rate at the knit manufacturer is 80 percent, justice-impacted employees stick around over 90 percent of the time. Both numbers are impressive considering turnover in manufacturing hovers around 40 percent.

By providing stable employment with sustainable wages, as well as a strong support system and access to resources, the company is able to achieve its primary goal: preventing people from going back to prison.

“The objective for us is to prove as low of a recidivism rate as possible, and right now, we're still at 0 percent over two years in,” Shupe said, comparing the numbers to California’s overall average rate of 50 percent. “It just goes to show, if you have the right wage, if you have the right community, the right support, if you create a culture that's about self-improvement and optimism, then you can make huge impacts in the labor market. So we're trying to evolve this further.”

A model for other employers

Part of evolving further is sharing the SecondStitch model with other employers. Shupe likened doing so to a nonprofit franchise model. Most of FutureStitch’s website is sparse, but a lot more money and effort was poured into the dedicated SecondStitch pages, he said. That’s because, in addition to providing employees with resources, it gives the framework for other employers to learn from and eventually emulate.

So what’s stopping employers from jumping on the bandwagon right away? “I think it's just a risk tolerance thing,” Shupe said. “There's this general sensitivity that I think sort of pushes the executive or the founder to pause … They're nervous that employing an individual like this — who may have a history of selling drugs, or a history of prostitution, or whatever — is going to create a legal liability for them. And it couldn't be further from the truth.”

In fact, the only risky situations FutureStitch has experienced came from employees who had never been incarcerated, Shupe said. He’s hopeful that by showing just how much the company benefits from increased retention and production, other employers will see the value of offering former offenders a second chance with the necessary programming.

“When you give out trust, when you give out empathy and love for somebody else, it reciprocates. And that's what we've learned here. Most of the people that we've hired from the system were never really given trust,” Shupe said. “It's interesting what happens when you give somebody trust first, instead of giving them cynicism … You get so much more passion and you get so much more loyalty.”

Homepage image courtesy of FutureStitch.