Drought Forces Santa Barbara to Reactivate Desalination Plant

California is in desperate need of water. The state is in its fourth year of drought. Earlier this month, Gov. Jerry Brown issued mandatory water reductions, directing the State Water Resources Control Board to reduce city and municipal water use by 25 percent. It’s the first time in California history that a governor has issued mandatory water reductions.

One California city is turning to a source of water located up and down the state’s coast: seawater. The city of Santa Barbara is re-activating a seawater desalination plant that hasn’t been used in over 20 years. (The plant opened in 1992 but closed three months later.) Desalination plants are generally last-resort measures because they are energy intensive and costly. The desalination plant in Santa Barbara may cost five times the amount the city pays for reservoir water.

The plant is for “emergency water supply,” according to the city’s website, and was constructed as a response to the severe drought from 1986 to 1991. However, the city shut it down “due to sufficient freshwater supplies since 1991” and put it in long-term standby only to be re-activated when water supply demand can’t be met by any other means. On Feb. 11, 2014, the city of Santa Barbara declared a drought after three years of below average rainfall. Two reservoirs, Cachuma and Gibralter, supply most of the city’s water, but they are at low levels. The city also gets some water from the State Water Project.

In May 2014, the city council authorized a $746,025 contract for preliminary design services to re-activate the desalination plant and could award the construction contract "as early as April 2015.” The final decision will be delayed “as long as reasonably possible,” because re-activation will cost up to $40 million, and the city estimates it will take 12 to 15 months to re-activate the plant. Annual operating costs will cost an estimated $5 million at full production and $2.5 million in standby ready-state mode. The city plans to pay for the plant by taking out a loan.

Other desalination plants are also in the works in California. The central coast town of Cambria opened a brackish water desalination plant last year. The plant is expected to cost between $5 million and $8 million and will supply 35 percent of the city’s water use. Cambria desperately needed the desalination plant because it faced a severe water shortage. In January 2014, the city faced running out of water in three to six months and issued mandatory water restrictions. A potential brackish water desalination plant in Marina, a town in Monterey County, is in the permit stages and construction is slated to start in late 2016. Monterey County faces a water shortage due to over-drafting of the Carmel River.

In San Diego County, Carlsbad is building a seawater desalination plant. When completed, it will be the largest in the U.S. but will only supply about 7 percent of the county’s water use. Clearly, during a historic drought every drop counts.

Image credit: Michael Theis

From Nonprofit to Social Profit: Exploring Assessment For Social Good

This is an excerpt from the recently released book "The Social Profit Handbook: The Essential Guide to Setting Goals, Assessing Outcomes, and Achieving Success for Mission-Driven Organizations."

By David Grant

Imagine an executive director of a social profit organization. She is working late the night before a board meeting, completing a proposal to a local foundation, one to which she has applied before. The proposal form asks, “By what measurable outcomes will you determine the success of your work?” She repeats the metrics she reported on last year: number of workshops offered; number of people served; scores on evaluation forms at the end of workshops. But she can’t help but feel something is missing. She would like to describe the biggest change the organization made that year, but that would mean describing the big mistake that caused it as well. Maybe not.

Imagine a foundation officer receiving the latest proposal from this social profit organization and re-reading the report submitted on the previous year’s grant. It says the organization served 1,200 people, a 20 percent increase from the year before. She asks herself: "But is that good? Should it have been 30 percent? And how well were they served?" She reads the report, which says in effect that social problems are getting worse but everything is going better than ever with this organization and the foundation should continue in its wisdom and generosity with ongoing funding. The foundation officer thinks: This feels more like a dance than an evaluation.

These people deserve a better assessment system. And so do the people this social profit organization serves.

How we think about assessment is significantly affected by how we think about measurement. Social profit does not have a standard unit of measure, like a dollar, a centimeter, or an ounce, and thus is difficult to measure. Some would say it is impossible to measure. Yet talk of measurement is everywhere in the social sector. The public and politicians question the efficacy of the sector and ask for proof of results. Board members seek ways to assess progress over time. Funders ask for hard evidence of impact.

Much of the talk has to do with “metrics” and “outcomes,” and technology has given us the chance to gather, analyze, and present data as never before. As a result, most organizations in the social sector choose key metrics and keep track of them. We describe our goals in numbers, and indeed, metrics can be important.

The case for further investment in social rather than financial profit is bolstered by a body of metrics associated with key indicators: percentage of a population suffering from diabetes or obesity; percentage of young men in prison in the United States, of which races and ethnicities; parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere; number and size of farms being managed sustainably; a nation’s score on the United Nations’ index of “material well-being of children”; data on infant mortality and life expectancy. The list goes on.

Yes, metrics can focus our attention and increase our motivation. But as we know, setting targets does not necessarily help us meet them. We must ask whether this data is making our organizations any better in our internal workings and in fulfilling our missions.

Who measures what and why?

When I was at the Dodge Foundation, I remember interviewing the founder and executive director of an organization in Newark that offered an arts education program designed to be a deep, transformational experience. Anecdotal evidence suggested that it was; the program seemed to be profoundly changing the lives of the young people who participated. Yet the ED was holding his head in his hands as he told me about a recent visit from another foundation officer, a key backer of this program: “All he said to me was, ‘You have to get your numbers up. You have to get your numbers up.’”

Does the number of kids in a program trump the quality of the program when assessing whether or not it is successful? It can and often does if there is no qualitative assessment that defines a different vision of success. For better or worse, measurement becomes a proxy for intention and values.

It is hard to argue with the foundation officer’s intention to serve as many young people as possible. But that was not the executive director’s intention certainly not his highest aspiration. He did not have the capacity to do that. He did have the capacity, and it was his mission, to change some number of young lives through the arts. But there was no metric for what mattered most to him, nothing with which to make an alternative case. This is a familiar story.

In workshops with social profit leaders, I sometimes ask, “Do you feel you are measuring what matters?” and more often than not, I get a quick no. Frequently, they say they did not think they had the option to measure what matters to them — and besides, they say, it wouldn’t be a valid measure, would it?

This is a critical question. At least part of the moral of the story is that if you do not define and assess what matters to you, someone else will do the assessing of your work, based on what is important to them. The other part involves an assumption and a question: What holds us back from thinking our internal, homegrown assessment would have legitimacy?

Validity and reliability

We live in an age when measurement and its uses in assessment and evaluation have become a serious science. Indeed, when a measure itself has to meet standards — think of the SAT or the Richter scale — we quite properly train our attention on those standards. Is it accurate? Is it reliable, which is to say does it give consistent results? Is it valid, which is to say does it measure what it is supposed to measure? These criteria are extremely important if a carpenter is measuring for a shelf, or a coach is weighing in wrestlers before a tournament, or a doctor is drawing blood to determine levels of uric acid. But does a measure always have to meet strict criteria to be helpful? I think we get confused over whether it is the measure that matters or what is being measured. We get intimidated by the science of measurement, forgetting that, in the words of change expert Michael Fullan, “Statistics are a wonderful servant and an appalling master.”

We find ourselves arguing over whether a measure of levels of quality can ever be accurate or valid. But what if we were able to agree that a measure is accurate enough, or valid and reliable enough, for us to take sensible and appropriate action based on what we learn from it? This question is important because we know any measure of social profit will never have the consistency we seek in standardized measures, nor the precision.

I know from the foundation perspective how difficult it is to compare the outcomes of two different arts education programs, let alone weigh the relative benefits of preserving a hundred acres of farmland or providing “talking circles” for troubled adolescents. But I also know how enthusiastically we responded to our grantees who had a process for identifying community needs, priorities, values, and visions, and who described in detail their aspirations and their plans for achieving them.

We did not talk about criteria of validity and reliability, because they were not the main point. We were basing our social investments on something else — a clear process that led to clear benefits, even if those benefits were described in words instead of defined by numbers.

Measurement and accountability

I remember a time early in my career, when my wife and I founded the semester program at the Mountain School, and we were scheduled to have our first visit from the State of Vermont. I prepared voluminous material about the new educational program and was excited to talk about its innovations: the way the English and science courses were taught in relation to each other and to our rural environment; the use of student journals for personal reflection and group process; the three-day solo camping trip; the work program; the student-led morning meetings. You must be shaking your head at my innocence.

The visit focused on two things: whether the furnaces were safe, and whether the kitchen was up to code. This was my introduction to the idea that while program performance may be foremost in the minds of social profit leaders, it may not be in the minds of their outside assessors.

Indeed, social profit organizations are accountable in at least two major areas aside from program performance: keeping their operations legal; and appropriately managing their finances. And because many social profit organizations receive government funding, they soon learn what governments value most — compliance with minimum standards in these areas, defined by law. The danger of this situation is obvious.

In a sector where many organizations and leaders are struggling to survive, they respond first to the immediate incentives in front of them to be compliant in all legal matters and in financial accounting and reporting. This compliance takes more time than we have, and we get used to the idea that assessment and evaluation come from the outside world.

But the outside world, particularly government, is not pushing on quality of work or level of service to clients and constituents, because they don’t have a measure for it beyond numbers served. There is no law that we have to be great at what we do. We should train ourselves to ask, Whom does this measurement serve? I’ll never forget the first time I realized as a teacher that the primary purpose of the SAT was not to help my students; it was to help adults choose among them.

Similarly, traditional outside measures of the work of individual social profit organizations are not designed for them; they are designed to make distinctions among them. So, surprisingly, measuring program performance seriously, honestly, rigorously, continuously, in a way that can inform and improve our work, is up to us.

It is critically important to do so despite the dearth of outside incentives, because that is where social profit lies.

Measuring what matters

It is helpful when thinking about measurement to remember the lines often attributed to Albert Einstein: “Everything that can be counted does not necessarily count; everything that counts cannot necessarily be counted.”

I am arguing that there are particular kinds of social profit that resist quantification, that resist standard measures, that are hard to pin down because they are dynamic in themselves, but are at the heart of how we imagine our missions being realized in the world. Faced with the realization that we will never find a common unit for these visions of social profit, we have two choices. We can say it cannot be measured, or we can measure it ourselves in the manner that social profit demands: a combination of pertinent metrics and a qualitative description of that social profit that can only be created by the people who are providing and receiving it. We must envision and define and then reflect and redefine these visions of success, believing that “if you measure what you value, people will value what you measure.”

David Grant is the author of "The Social Profit Handbook: The Essential Guide to Setting Goals, Assessing Outcomes, and Achieving Success for Mission-Driven Organizations."

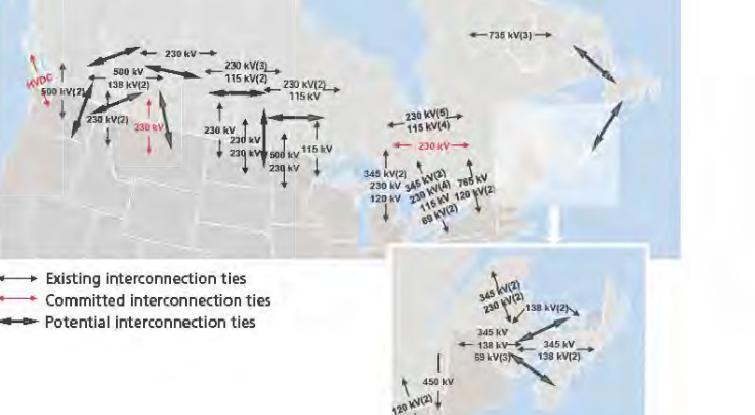

Canada's Green Energy: The Push for a New East-West Grid

The United States and Canada have a long history when it comes to electricity supply and demand. Canada provides power to U.S. communities across 35 transmission points, stretching across a north-south grid that ranges from the the Pacific coast to the Eastern Maritimes. Both countries benefit from this relationship: The U.S. is able to feed power-hungry areas like New York, and Canada benefits financially from its expansive wealth of hydraulic power and other sources.

A growing number of Canadian researchers and engineers are questioning the logic of this dominant north-south grid these days, as Canada begins to reevaluate how it can become more sustainable.

Last month, a group of 60 researchers published a report suggesting that realigning Canada's grid on an east-west axis would bolster the economic resilience of its grid as well as make Canada a more sustainable powerhouse. Acting on Climate Change: Solutions from Canada's Scholars takes an inquisitive view of the way Canada shapes its energy production and use. And from the authors' standpoint, redesigning where the power goes would not only allow those sustainable and power-rich provinces to spread the wealth, but it will also help provinces that are still digging themselves out of a carbon-based power dependency, like Alberta.

This is hardly a new idea. The Canadian Academy of Engineering has been working on this concept for some years, providing data on how Canada could not only transform its grid but its approach to the future as well.

"As Canada enters the 21st century, it remains blessed with an abundant array of energy resources. There will be opportunities for managing these big projects as an energy system which will go beyond the interest of individual companies acting alone, and require a new vision of Canada's energy future," say researchers at the Energy Pathways Taskforce, a project of the Canadian School of Engineering, which authored several reports on ways that Canada's energy sector can become more sustainable.

Part of that new vision includes enhancing electrical supply that links provinces like Quebec and British Columbia, which thrive on their hydro power, with Prince Edward Island, which has no power source.

"Canada at present has more electrical connections with the U.S. than it has among all the provinces (34 to the U.S. compared to 31 among provinces)," explain the authors of a 2012 report from the Canadian School of Engineering. They go on note that many of those north-south connectors "can transfer quantities equivalent to the output from major hydro or nuclear plants."

A pan-Canada grid wouldn't necessarily detract from the services provided to the U.S., say the authors, who point out that an interconnected grid between Canada's provinces and territories that incorporates hydroelectric generation, tidal power, wind and other sources would allow the country to develop and facilitate "the flow of other low-greenhouse gas renewable power to electricity markets."

Other benefits of the proposal, which incorporates 17 potential lines between the northeast tip of the country and Victoria/Vancouver at the southwest, include:

- Pioneers the development of new technologies

- Establishes incentives for bringing those technologies to market

- Potentially reduces long-term electricity rates across the country

Threats to the plan include the "continued interest of U.S. utilities to work on the feasibility of their on continental grid." The report points out that a dominating weakness of the plan is the political will of stakeholders across Canada to invest in and agree to the plan. One of the reasons for this stumbling block is that under the Canadian Constitution, power generation is administered by the provinces, so consensus must be reached before a new grid is established. Another challenge is its geography: Areas like eastern British Columbia's formidable Rocky Mountains have at times presented obstacles to new energy and transportation corridors.

The CAE task force estimates that preliminary costs of the pan-Canada grid would be about $25 billion, and it would take a couple of decades to build. To do this, new hydroelectric and tidal generating systems would need to be constructed in various parts of the country, adding another $2.5 billion to the price tag.

But the 60 Canadian researchers that authored this most recent report on Canada's green energy options estimate that Canada could conceivably reach "100 percent reliance on low-carbon electricity by 2035" if it built an east-west smart grid. Combined with Canada's current push for low-carbon transportation, say the authors, this innovative approach could support a "transportation 'revolution."

"In the short term, we believe that Canada, in keeping with its historical position of aligning with U.S. targets, could adopt a 2025 target of a 26 to 28 percent reduction in GHG emissions relative to our 2005 levels."

The world will be watching, Canada.

Canada's renewable energy potential map: Dialogues on Sustainability: Acting on Climate Change, Solutions from Canadian Scholars

Images of Canada-US power grid and proposed east-west grid: Canadian Academy of Engineering: Winning as a Sustainable Superpower, Vol. II

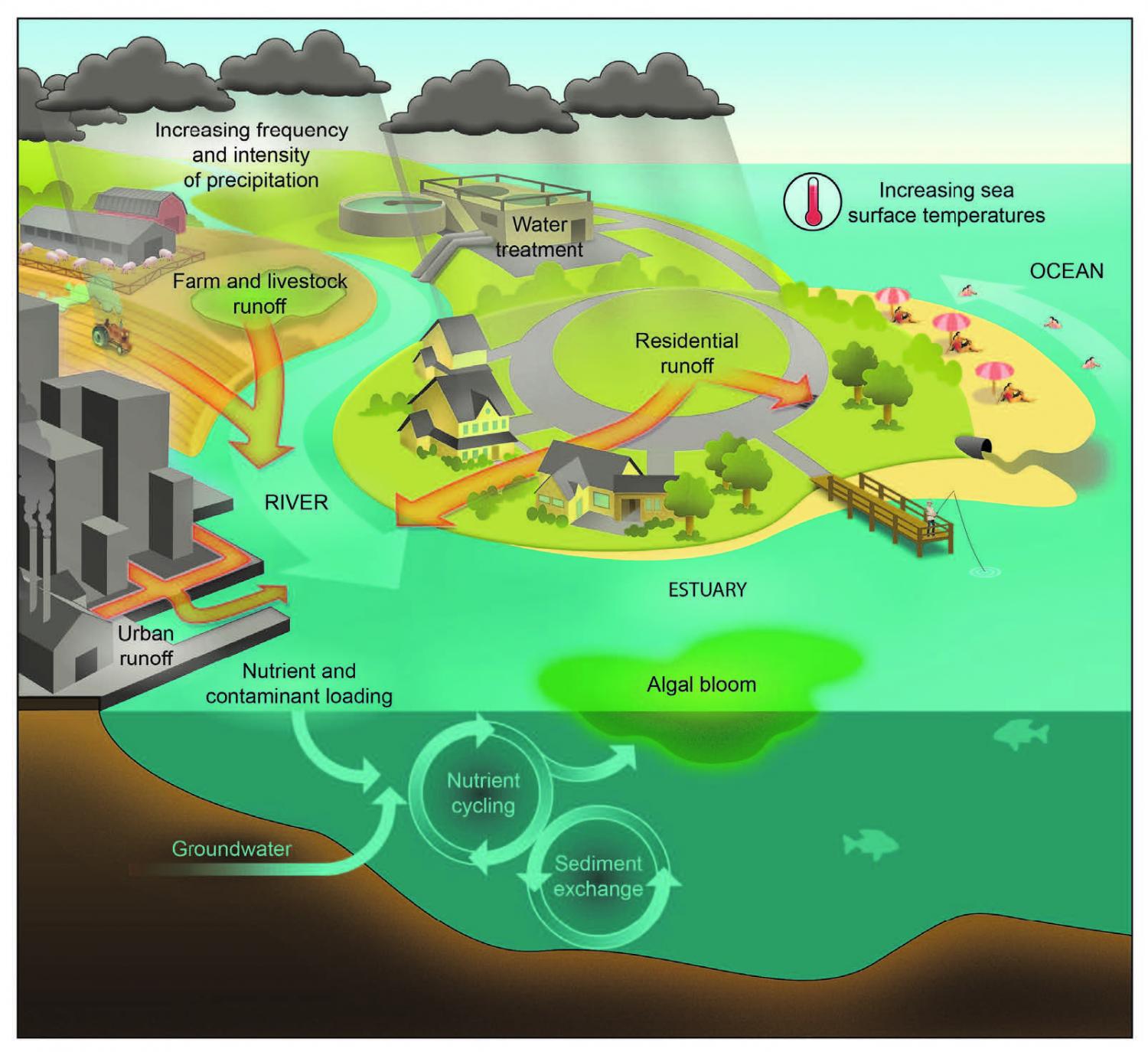

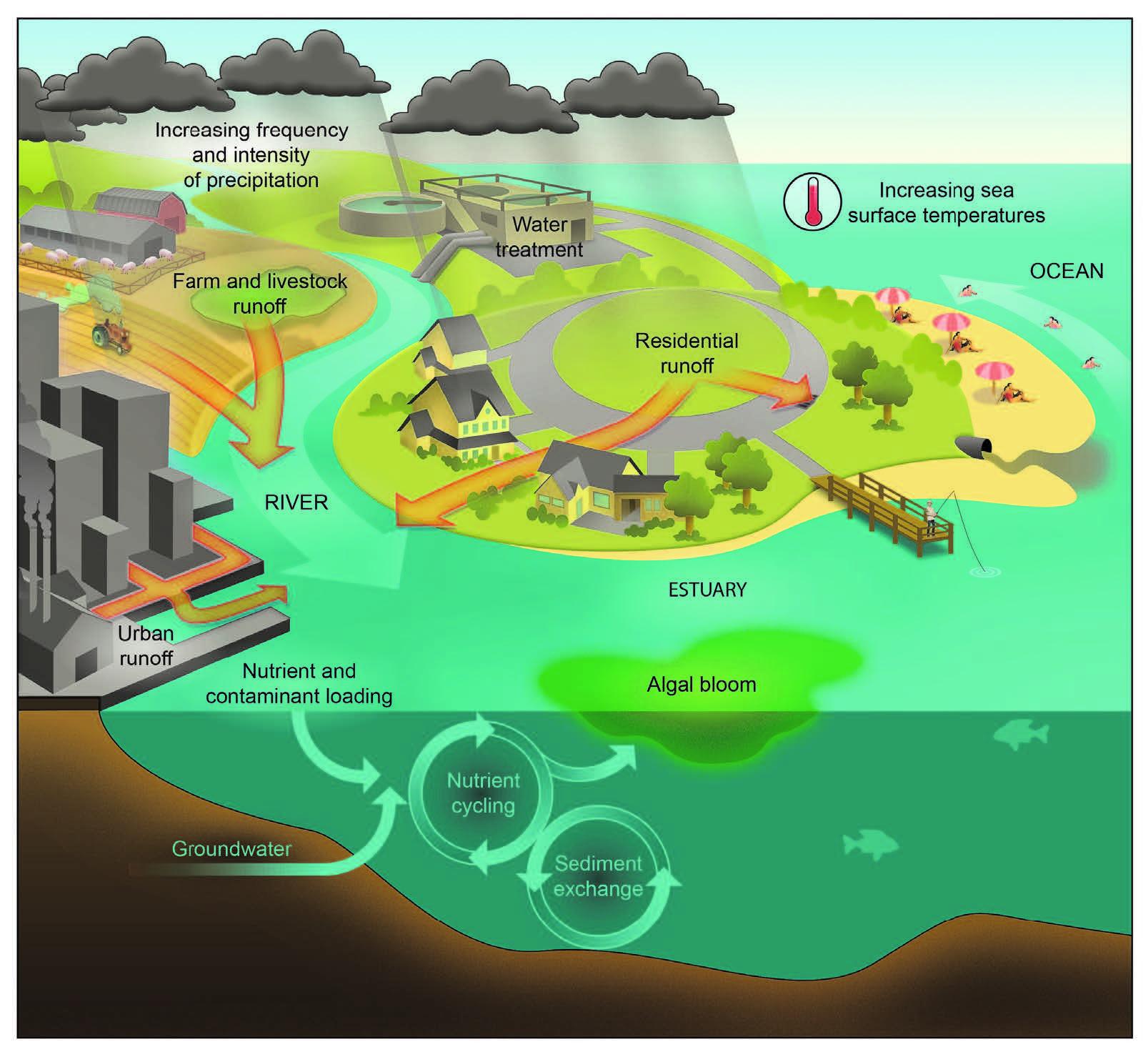

Report: Climate Change is Dangerous to Your Health

Climate change is not only bad for the environment and the planet, but it’s also bad for your — and your children’s — health.

It’s all connected, and at some level we know this, because, well, look out the window and read things besides right-wing, climate-denier talking points. But how serious are the health-related impacts?

Really, really serious, according to a 405-page draft climate and health assessment report from the U.S. Global Change Research Program. Consider a huge increase in the tick and mosquito populations, for one thing, along with increases in airborne and waterborne pathogens.

Climate change is threatening human health and well-being in many ways, say the authors of The Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health in the United States: A Scientific Assessment. The draft report, which is open for comment, was developed by the Global Change program's Interagency Group on Climate Change and Human Health. It's part of the sustained National Climate Assessment and was called for under the president’s Climate Action Plan.

The tone is set in the first paragraph of the report: “Climate change is a significant threat to the health of the American people.”

It continues: “The Third National Climate Assessment confirmed the evidence for human-induced climate change and described how impacts are increasing nationwide. Rising carbon dioxide concentrations, and the resulting increases in temperature, changes in precipitation, increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and sea level rise endanger our health by affecting our food and water sources, the air we breathe, the weather we experience, and our interactions with the built and natural environments. As the climate continues to change, the risks to human health continue to grow.”

Current and future impacts of climate change expose more people in more places to more public health threats. The report notes that in the U.S. we’ve already seen climate-related increases in “exposure to elevated temperatures; increases in the frequency, severity, or duration of certain extreme weather events; degraded air quality; diseases transmitted through food, water, and disease vectors (such as ticks and mosquitos); and stresses to our mental health and well-being.”

Nearly all of the threats will only get worse over time or at certain times of the year. In addition, people living in regions not previously exposed to these threats will also be exposed.

Here’s a taste of what’s in store for us:

- Increases in temperature-related deaths: Future climate warming could lead to “thousands to tens of thousands additional deaths” each year from heat in the summer.

- Rising temperatures, increasing precipitation and increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide are expected to contribute to increased levels of some airborne allergens and associated increases in asthma episodes and other allergic illnesses compared to a future without climate change.

- Climate change is expected to alter the geographic and seasonal distributions of existing vectors and vectorborne diseases. Ticks and mosquitoes will become more numerous and widespread.

- With respect to water, algal toxins will likely rise, and recreational waters and sources of drinking water will be compromised by “increasingly frequent and intense extreme precipitation events.”

- Extreme weather events and storm surges will likely increase the risk of failure of, or damage to, water infrastructure for drinking water, wastewater and storm water.

- Elevated sea surface temperatures and increases in certain weather extremes associated with climate change will increase human exposure to water contaminants in food, and will alter the incidence and distribution of pests, parasites and microbes.

- Rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere will degrade the nutritional value of food crops, including wheat and rice.

Then there’s health impacts from projected increases in the frequency and/or intensity of extreme precipitation, hurricanes, coastal inundation, drought and wildfires in some regions of the United States. “Adverse health outcomes associated with exposure to extreme events include death, injury, or illness; exacerbation of underlying medical conditions; and adverse effects on mental health.”

When finalized, which is expected early next year, the report will provide some context and a baseline for understanding Americans’ changing health risks.

In short: The climate change prognosis on health in the U.S. is pretty bleak and getting bleaker.

Image: Illustration from the USGCRP draft report showing the links between Climate Change, Water Quantity and Quality, and Human Exposure to Water-related Illness

Some Question New U.S. Plan to Combat Illegal Fishing

Editor’s Note: This post is an entry in the 5th Annual iPura Tweet & Blogfest at Seafood Expo 2015. It originally appeared on the Good Catch blog. Read all of the Blogfest entries here.

By Ret Talbot

Those of you who followed my coverage of the 2015 Seafood Expo North America (SENA15) know I chose to focus on aquaculture this year. Those who are regular readers of the Good Catch Blog know my usual beat is wild fisheries, and while I plan to talk about fish farming more this year, I will still primarily focus on wild-harvest.

As such, I was keen to hear the U.S. government’s announcement at SENA15 regarding an action plan, formulated by the Presidential Task Force, to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing and seafood fraud.

The plan, which will be implemented by the departments of Commerce and State, lays out a broadly coordinated plan that has been called “historic” and “unprecedented.” While there has been a great deal of improvement in domestic fisheries from bait to plate, upward of 93 percent of seafood consumed by Americans is imported, and there remain significant concerns about many of the fisheries from which those imported fishes originate. As such, the U.S. government has strong incentive to make sure the majority of seafood Americans purchase is not undermining our own efforts at home when it comes to environmental and socio-economic sustainability.

“The Obama administration is committed to working to ensure that America’s fishing industry remains the heart and soul of coastal communities across the country,” U.S. Deputy Secretary of Commerce Bruce Andrews said during the announcement at SENA15. “The steps the United States has taken to be a leader in environmental stewardship are paying off. However, our nation’s fisheries remain threatened by illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and seafood fraud, which negatively affects our markets. The Task Force’s new strategic plan will aggressively implement recommendations to guarantee that U.S. fishing fleets remain competitive in the global economy.”

Addressing IUU fisheries on a global level is not without its challenges, and although the action plan is the result of a multi-stakeholder effort, a few of the specifics announced at SENA15 have received mixed reviews from the fishing industry. In particular, some in the industry worry that the way the government plans to address enforcement challenges could unintentionally harm the U.S. seafood industry.

Why address IUU and seafood fraud?

In general terms, addressing IUU fishing and seafood fraud is good for fisheries, fishers and anyone engaged in a legal seafood industry. At the broadest level, IUU fishing and seafood fraud threatens global food security, as an estimated 2.5 billion people rely on seafood for food and nutrition. IUU fishing also threatens fish stocks and ecosystems, as well as the fishers and fisher communities who depend on those ecosystems. In addition, IUU fishing provides a conduit for a host of other illegal activities, including human trafficking and smuggling of contraband, such as drugs and weapons.

Seafood is the most traded food commodity in the world, and fraud can result in economic losses in the billions of dollars. When seafood products are mislabeled in an effort to mislead consumers regarding species, origin or quality, it undermines the economic viability of trade. There are also health concerns associated with mislabeled products. It is estimated that at least 25 percent of seafood sold in the U.S. is mislabeled, and some estimates put that number closer to 35 percent.

While there are already laws in place to address many activities resulting from IUU fishing and seafood fraud, many of these laws are, according to government officials, difficult to enforce. In addition, the government has argued, “Several critical [domestic] statutes lack robust civil judicial and criminal enforcement authority, adequate administrative penalties, or appropriate forfeiture authority to address IUU and fraudulently marketed seafood products.”

As one government official commented off the record regarding the action plan and enforcement, “We’re going to give the law some sharper teeth.”

Questions regarding enforcement

Five of the 14 recommendations laid out in the action plan concern enforcement, and, not surprisingly, there are some concerns by those in the fishing industry about those recommendations.

“All I’ve got to say,” said Robert Becerra, during a SENA15 panel presentation, “is that when these regulations from the Presidential Task Force come into effect, hold onto your wallet, hold onto your shirt, hold onto your shoes and hold onto your pants because there’s going to be all sorts of new compliance requirements that are going to come on board that, at least for smaller companies especially, are going to be very, very difficult.” Becerra is a Florida Bar Board Certified Specialist in international law, specializing in civil and white-collar criminal litigation in matters involving international trade.

The five recommendations in the action plan that deal with enforcement are:

- Recommendation 8: Information Sharing

- Recommendation 9: Customs Mutual Assistance Agreements

- Recommendation 10: Species Name and Code

- Recommendation 11: State and Local

- Recommendation 12: Enforcement Authorities

The last, Enforcement Authorities, was the one that received a fair amount of attention and criticism during SENA15. Acknowledging there are “crucial gaps” in federal authorities that “prevent agencies from monitoring the entirety of the seafood supply chain,” the plan states:

"Agencies need to leverage existing authorities through stronger coordination and, where necessary, seek additional enforcement tools to address growing concerns over IUU fishing and seafood fraud, in particular the illegal entry of seafood products into U.S. commerce."

Coordinating across agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security, the Food and Drug Administration, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Department of Agriculture will allow for more effective inspection, verification and enforcement activities throughout the supply chain. The plan states that “the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act (MSA) prohibits the import of fish taken in violation of foreign law but effective enforcement of this prohibition requires the cooperation and coordination with border control agencies such as ICE HSI and CBP.”

The National Fisheries Institute objects to the government’s premise that it doesn’t already have the enforcement authority it needs to combat IUU fishing and seafood fraud.

“[Government agencies] should be coordinating already,” said Gavin Gibbons, an institute spokesman. “In fact, we hope these agencies have been coordinating all along. I am certain quite a few taxpayers would question why federal agencies need a task force to mandate such harmonization.”

Increased penalties: Lacey and RICO

In addition, the action plan calls for “tools such as increased penalties and administrative and judicial enforcement mechanisms.” While acknowledging that a number of these mechanisms already exist, a number of key statutory authorities “do not have adequate penalties or administrative and judicial mechanisms,” according to the plan's authors. Increasing penalties and administrative and judicial enforcement mechanisms under the new plan worries some in the fishing industry.

“It’s high profile,” Becerra said. “It’s a Presidential Task Force, and their going to put a lot of money and a lot of effort into it, and the government in my experience doesn’t put a lot of effort and money into things and then not bring cases at all against people — they just don’t do that. It’s the nature of the beast so to speak.”

Becerra pointed to the Lacey Act as an example. He believes many of the cases resulting from the government plan will be prosecuted under the Lacey Act -- and said that is serious business as-is. “The Lacey Act is going to be one of the things they’re going to use to go after people,” Becerra said at SENA15. “It’s a criminal statute — it’s very easy to violate it if you don’t have your ducks in order.”

“Under the Lacey Act,” Becerra continued, “it basically makes it a crime to import fish or traffic in fish that’s been caught illegally under U.S. or foreign law … They're going to have this requirement that you have to trace the fish and to show that it was legally caught in the waters from which it came from.” He went on to say that the levels of traceability for fish caught outside of U.S. waters would be, in his opinion, “pretty onerous and pretty difficult for companies to do, correctly at least.”

Becerra and others disagree with the plan, which suggests the Lacey Act has a very low civil penalty maximum. “Most people think of the Lacey Act as an absolutely nuclear approach to enforcement,” said John Connelly, president of the National Fisheries Institute. “I don’t think you’d have many of the business people agreeing with the comment that the Lacey Act is somehow inadequate because it has low civil enforcement. People go to jail — huge criminal enforcement in that area.”

Overreaching?

The government argues that enhanced enforcement authority is necessary because existing enforcement authority doesn’t go far enough. “Tools such as increased civil monetary penalties, clear forfeiture authority, and increased authority to impose criminal fines and penalties, including through the application of laws related to money laundering and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) are needed to deter illegal activity motivated by the large profits that may be associated with IUU fishing and trade in the resulting product,” the Task Force said.

Connelly made NFI’s position clear on this point during the panel discussion following the government’s announcement at SENA15. He warned against “enforcement overreach” and expressed concern about how laws not intended to address IUU fishing and seafood fraud would be used.

For example, he pointed to RICO and recalled a high-profile story about seafood fraud that ran in the Boston Globe in 2011. “A famous chef [in Boston] mislabeled some sablefish and called it butterfish,” Connelly said. “He said ‘because it rolled off his tongue more easily’—that was his exact quote. That doesn’t make him Don Corleone. That doesn’t make him John Gotti. So, we’re concerned about the concept of overreach in enforcement in using these laws that were unintended for these kinds of things.”

Moving forward

While there are many contentious issues for the fishing industry in the government’s new plan, overall most in the industry agree that addressing the problem of IUU fishing and seafood fraud is important. Many are supportive of a risk-based traceability program to track seafood from harvest to entry into U.S. commerce, so long as that program would not ultimately cost those in the seafood industry who are operating legally.

The fishing industry would like to see the program remain targeted on those species and fisheries that pose the greatest risk, and they worry about the government’s stated plans to expand the program to all seafood entering U.S. commerce by December 2016.

“Why are we talking about expanding to all fish when a risk-based system clearly makes the most sense?” asked Gibbons. “If tilapia is not being mislabeled and is not even a wild-caught species, then why are we working to expand the effort to tilapia? This would ultimately cost and negatively impact species that are not suspected of fraud or IUU.”

As the action plan moves forward, the government will solicit additional input from all stakeholders prior to final rule-making on various aspects. For more information, or to learn how and when to submit a comment, check out the National Marine Fisheries Service International Affairs webpage.

Image credit: U.S. Coast Guard

Ret Talbot is an award-winning freelance science writer and photojournalist with nearly 20 years of experience covering stories from some of the more remote corners of the globe. From the icy summits of the Andes to the reefs of Papua New Guinea, his assignments have taken him off the beaten track and put his readers face-to-face with stories of adventure, new ideas and innovative approaches to commonplace issues. His current work focuses on the intersection of fisheries, science and sustainability.

Reflections from Career Investor Amy Domini

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of Green Money Journal on “Women and Investing.” Read more excerpts here.

By Amy Domini

"Women and Investing." The feminist in me is struggling. The suggestion of a special category implies a difference, and a difference, when it comes to women, tends to mean a weakness. Women and the sciences, women and sports, the debates about women’s powers make me, as a woman, uncomfortable. But then I review my own story.

I manage assets for people who are interested in socially responsible investing. Over 60 percent of the money I manage belongs to women. I also run a socially responsible mutual fund. It has 55 percent female investors, while the average mutual fund is 45 percent. Women have a special connection to socially responsible investing.

There are two approaches to the topic of women and investing. One involves women managing investments for others. The second involves women with money to invest. Certainly the field of socially responsible investing has many women in leadership roles, and the clients we serve include many practical and idealistic women. Is the female investor different? If so, how and why?

I looked to my own career path for clues.

I entered the field of finance during the mid-1970s, when women were clearly anomalies. There had been a feminist revolution during the preceding decade but it was our mothers who read all those books and felt the seismic shift that was beginning. We had more of a flower-child mentality. I floated through early life without the slightest ambition. My job as a photocopy clerk in a stock brokerage firm was just a job, not a career. When, after a couple of years with the firm, I became registered to sell securities, I did so for the raise, not the responsibility. When, four years later, I was introduced to a client as the firm’s first female stockbroker, I was surprised. It hadn’t occurred to me before. I did not self-identify as a woman, but as part of the team.

The initial years were tough. I had two babies and worked though the pregnancies in offices filled with cigar smoke. I took a week or two for maternity leave (three weeks was considered long then). But I’d been brought up hearing, “Never mind all that, just pull up your socks and keep marching.” It didn’t occur to me that there might be a different way. Plus, I had passion; I wanted the world to understand something I had figured out: The way you invest matters. Investors can demand disclosure and better reporting from the companies they own. Clients do not need to sully their hearts by investing in filth.

In those early days I saw many women do amazing things. Joan Bavaria launched Trillium Asset Management to manage money responsibly. Joan Shapiro, who worked at the South Shore Bank of Chicago, showed the difference that a caring bank could make to a community. Alice Tepper-Marlin, whose Council on Economic Priorities tracked corporate spending on elections, helped us understand the many ways that corporations affect our daily lives. Medical Mission Sister Regina Rowan, an activist shareholder, was famous for having a seat in the front row at Merck’s annual meeting. Each year she rose to ask the company to again pledge $100 million worth of Ivermectin to the poor, thereby reducing the scourge of river blindness. There were men too, important leaders, but the women made it more appealing to me than my male-dominated experience in the brokerage firm did.

I joined the Loring, Wolcott & Coolidge Office in 1987, where I founded the practice now called the Sustainability Group. With my partners’ permission, I also founded Domini & Company -- which became KLD Research and Analytics — and the Domini Social Index Trust, which became Domini Social Investments. I worked very hard, but I cared so deeply about moving the field forward that it was thrilling.

In terms of being successful as a money manager, there are two important elements. One is the ability to attract and maintain clients. The other is the ability to pick investments that outperform the market. The rules are clear, so a pure meritocracy should exist. That it does not is due to other factors, because on the two criteria that matter, women compete well.

Thinking it through, it was my field, socially responsible investing, that proved me as a money manager. I believe completely in the importance of the field and feel such pride when we have small wins, that my work was never a job so much as an identity. I loved helping people figure out how important socially responsible investing is, and thus I gathered many clients quickly. I also loved learning about companies and what makes them great, which helped my investments work out.

But what about the other side of women and investing — the client side? Last year Wells Fargo issued a study on affluent women and their investment habits. Like other studies, it points out that women are reluctant to manage their assets, even women who have successful careers. In this study, it was found that among affluent women, only 43 percent of single women and 34 percent of married women manage the investments the household makes.

This reluctance to be the investor, in my experience, leads to careful review before taking steps. Women study what investing is before they make a move. They read Internet stories and ask friends. Eventually, they learn about investing with purpose, in the triple bottom line of people, planet and profits.

See Amy's complete article here.

Article by Amy Domini, partner in The Sustainability Group in Boston where she manages roughly $1.1 billion in liquid assets for high net worth families. Additionally she is the founder of Domini Social Investments (www.domini.com), a New York City based mutual fund family with $1.6 billion under management. She is widely recognized as the leading voice for socially responsible investing. In 2005 she was named to the Time magazine 100 list of the world’s most influential people, and in 2009 Time listed her as one of 25 “Responsibility Pioneers”. In 2005, President Clinton honored her at the inaugural meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative.

A Sustainable Supply Chain in the Garment Industry Saves 4 Major Companies $15M Annually

The global textile and garment industry is one of the world’s largest polluters due to its massive impacts on water, soil and of course, people. While consumers are becoming more aware that their fashion choices have on distant places such as Bangladesh, China and India, much work still needs to be done until the industry can be truly described as responsible and sustainable.

While more multinationals insist they are changing their ways, the non-profit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) alleges that only five percent of the companies they monitor consider environmental performance when it comes to making decisions involving their supply chains. To that end, an NRDC report released today covering a pilot project within the fashion industry should serve as a wake-up call to companies that more environmentally responsible choices can improve their reputation while resulting in financial savings.

The report, which outlines the success NRDC’s Clean by Design program achieved in some textile mills in China, offers suggestions on how improving production efficiencies can save money and become more environmentally responsible. NRDC launched the program in a partnership with the International Finance Corporation (IFC) last year in Shaozing and Guangzhou, two cities that are large hubs of Chinese textile manufacturing. Of the over 100 mills that showed interest in the program, 33 were selected to participate. The results, claims NRDC, resulted in significant improvements: 61,000 tons of coal not burned; 400 tons of chemicals not processed; 3 million tons of water saved; 36 million kilowatt hours of electricity conserved; and on the financial side, US$14.7 million dollars saved over the year, with a five year projection totaling US$56.4 million.

The four companies partnering in this project, Gap, H&M, Levi Strauss and Target—and of course their suppliers—were the beneficiaries of these cost savings. At a time when more consumers understand the ravages of fast fashion and the water footprint of their favorite pair of denim jeans, these companies’ competitors should take notes from this project’s report and find ways to work with their suppliers in order to reduce their costs and environmental burdens. And for those in the finance department who only care about the numbers on the ledger, the NRDC points out that some of the biggest savings come from changes that result in forehead-slapping moments. Investments in more efficient motors and lighting, for example, generated the biggest cost savings at many of the mills.

Improvements at one mill alone resulted in 25 percent of the project’s total cost savings. In operation since the late 1990s, the mill dyes and prints woven textiles while employing 6,500 people. Most of the US$3.6 million savings came from retrofitting machines and installing new equipment to conserve water and energy consumption. The collection and reuse of water from dyeing machines alone saved over 500,000 tons of water a year—water that otherwise could have ended up discharged back into the local environment. The NRDC estimated that they payback time for the 13 projects at this mill had a payback period of 13 months—for other mills, the payback time from making similar improvements was far shorter.

In the end, one of the NRDC’s high-level recommendations should be compelling to any supply chain manager: the adoption of 10 best practices can account for 30 percent of a textile mill retrofit's total water and energy savings, in addition to a financial boost that would please any executive. And in China, considering the fact the country is moving towards capping its coal use by 2020, the fact that a relatively small investment can result in big savings cannot be ignored.

Image credit: Jo Sau

Whirlpool and Habitat for Humanity Partnership: True Corporate Giving

When it comes to cause marketing, there may not be a more mutually beneficial partnership than the 16-year relationship between Whirlpool and the nonprofit Habitat for Humanity. What began with appliance donations has become one of Whirlpool’s most successful corporate social responsibility programs. It is hard to argue with the numbers: over US$85 million in donations since 1999, 8,000-plus company employees who have volunteered with Habitat for Humanity, and a renewed lease on life for over 100,000 families.

Along with its commitment to manufacturing in the United States, the reputation of its products and services and, of course, its financial strength, Whirlpool’s corporate citizenship is one reason it is consistently mentioned as one of the country’s most admired companies.

To learn more about this partnership, I spoke with Deborah O’Connor, the director of global corporate reputation and community relations at Whirlpool Corp.

The relationship started when Whirlpool agreed in 1999 to donate a range and refrigerator to every house Habitat for Humanity builds in the United States and Canada. The program expanded from North America across the globe, with programs launched in regions including Europe, Central Asia and South Africa. Over the years the partnership grew deeper on many levels. Whirlpool began to donate unsellable appliances to ReStores, the home improvement stores and donation stores that are a significant revenue generator for Habitat for Humanity. The company also works with Indiana University on annual home-builds near its Bloomington campus.

Whirlpool’s bonds with Habitat for Humanity became even stronger as the company began to help fund the construction of homes in regions where it has major offices, customer service centers and factories. Those locations include Benton Harbor, Michigan; Clyde, Ohio; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; and Tulsa, Oklahoma. “It makes more sense to us to stay local,” explains O’Connor, “and spend money on actual construction materials to build homes rather than on marketing or flying people across the country to build a house.”

The company shares some of its success stories on its social media channels, but rarely discusses the campaign in its marketing and advertising. “We ran some promotions in the past, but we asked ourselves, ‘Where do we want to spend the money—isn’t it better to spend it on what we do?’” explains O’Connor. “Maybe when you go buy an appliance, we hope you select one of our appliances, but there are many important reasons why we work with Habitat for Humanity.”

For O’Connor and the thousands of Whirlpool employees who have volunteered on a Habitat for Humanity project, the experience is one that is deeply meaningful and personal. “With our unique partnership, we can provide products and services that others cannot provide,” says O’Connor, “and we also know that in providing a family a home, we offer a more structured life for their children. We in turn have the opportunity to stand next to them, to meet them and learn about their situation.

“It’s pretty moving to see someone understand that all these people are helping them build this house and that they are so grateful. I still get notes from people on homes I have helped with, especially around the holidays. They are so excited to not only have a home for the holidays, but now they can even host on a Thanksgiving. This program creates and strengthens families, it creates structure in so many ways -- a place for kids to do their homework; and families don’t have to go to a laundromat to get their laundry done. The list of benefits can just go on.”

One of O’Connor’s favorite stories was from about five years ago when Whirlpool and Habitat for Humanity worked together to build 10 houses on a block in Dallas, Texas. A woman who was going to move into one of these new homes was at first shy about wielding tools. “By the end of the week, I saw her grab a hammer out of another person’s hand, and it struck me how really it was a metaphor for what we do. She became empowered and did something she thought she couldn’t do. I’m always reminded of her as I work on other projects.”

The dedication O’Connor and other Whirlpool employees put into the company's work with Habitat for Humanity pays dividends in ways far beyond the company’s reputation and employee engagement. In her view, it ties into how Whirlpool as a company and brand has been part of the American landscape for over a century. “Cause marketing” almost sounded like a cliché to me as I listened to the enthusiasm O’Conner showed during the course of our conversation. The involvement with Habitat for Humanity is deep, as she explained. In addition to all of her other duties, she is often on the phone with her contact at the nonprofit at least once a week. Many corporate social responsibility programs I come across sound like little more than a checkbox for a company’s “do good” list, but what is going on between these two organizations is a genuine commitment.

“The reason why this partnership has lasted so long,” says O’Conner, “is because it’s a truly good fit for both organizations because we both get something out of it, and that is what’s most important.”

The success -- which has continued far away from Whirlpool’s headquarters in Benton Harbor, Michigan, and Habitat for Humanity’s head offices in Atlanta -- is a lesson for companies that are considering the launch of a cause marketing campaign. For it to work and have meaning, both partners should really be in it for the long haul. “It’s really just a matter of making sure that the fit is there for both organizations,” says O’Conner as we wrapped up our conversation. This has been more than a fit: This partnership has brought empowerment and joy to thousands that will last for years.

Image credits: Ann Schertz

Tackling the STEM Gap with Hacker Sarah Austin

In advance of today's Twitter chat about STEM Inclusion, I chatted with Sarah Austin (@sarahaustin), former SAP Hacker of the Year, Forbes 30 Under 30, to find out more. Join TriplePundit, SAP and our esteemed guest panel on today at 8 a.m. PST / 11 a.m. EST – at #SAPYouthChat.

TriplePundit: Hacker of the Year - impressive. What did you do to get that title?

Sarah Austin: SAP awarded me the title for winning so many hack-a-thons in 2013. The secret to winning hack-a-thons is combining art direction and good marketing with the fundamentals of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math).

3p: What are you up to now?

SA: Combining data science, marketing and product management, I work with companies to define their marketing messaging and assess the strengths and weaknesses of their competition in a process called broad listening. I have one of the few marketing firms that combines natural language processing, big data and online media to automate market research and competitive intelligence.

3p: You are an example of a success story for women in STEM -- Have you experienced any roadblocks along the way due to your gender?

SA: In 2012 when I was on Bravo's Startups Silicon Valley, I was quoted as saying, “people get intimidated because this package doesn’t usually come with a brain,” and people have made fun of me for saying it. But I have a “frumpy outfit” that I wear sometimes because sometimes it’s easier to put on ugly clothes than dealing with the common assumption that a well-dressed woman in Silicon Valley isn’t smart.

3p: Are you working on any initiatives to help young folks achieve what you have achieved?

SA: CodingFTW is working on curriculums for youth, and while it primarily promotes female diversity in STEM, it is at its core about making software development approachable to anyone.

3p: STEM inclusion is really complicated. What is one action our readers can take to improve diversity in these quality jobs?

SA: Get involved in your community. Volunteer at a local nonprofit that is helping to create opportunity through workforce development.

Fish Farming: Defying Conventional Wisdom

Editor’s Note: This post is an entry in the 5th Annual iPura Tweet & Blogfest at Seafood Expo 2015. It originally appeared on the Good Catch Blog. Read all of the Blogfest entries here.

By Ret Talbot

Each year I walk away from the Seafood Expo North America (SENA15) with a personal take-home point — something that, in addition to influencing my professional career as a writer, I can adopt in my personal life as a consumer. As I wrote last month, this year’s Expo inspired me to focus more on finfish aquaculture in both my writing and in my personal purchasing decisions over the coming year.

After several panel discussions, private conversations and interviews with SENA15 speakers and vendors, I believe more firmly than ever that the future of a truly sustainable seafood industry must include far more aquaculture effort supplementing well-managed fisheries. While I know many people agree with me based on the conversations I had at SENA15, I also heard loud and clear from some of my readers that there remain significant concerns about farmed fish.

Defying conventional wisdom: Great synergies to be had

Much of the work I do as a journalist covering fisheries at the intersection of science and sustainability focuses on wild fisheries. In particular, I focus on how sustainable fisheries can create economic incentive to conserve and can provide valuable income for working waterfronts. When fishers stay connected to the resource, we can gain so much in terms of both environmental and socio-economic benefit. Given that this is the space from which I often write, I understand why some of my readers may feel alarmed that I’m, as one reader wrote, “jumping on the fish faming bandwagon.”

I understand it, but I don’t agree.

Neither does Neil Sims, co-founder and CEO of Hawaii-based Kampachi Farms, and he said as much during a panel at SENA15 entitled “2 Billion People are Coming to Dinner, Let’s Feed them Fish!” During his presentation, Sims described his company’s trial of an unanchored, free-drifting fish culture system. While Sims believes open-ocean mariculture is the “only one real solution” for producing farmed fish on the scale required by increasing global demand, and while he is an unapologetic aquaculture evangelist, he doesn’t see fish farming as necessarily competing with wild harvest. In fact, he believes the two can be complimentary, especially in offshore federal waters, where there is currently no commercial aquaculture effort (that’s right, zero, but I’ll cover that in a separate post).

To prove his point regarding aquaculture and wild harvest co-existing, Sims described the response from some local fishers when Kampachi pulled the open ocean net pen at the end of the trial. He said, “We had fishermen grabbing us by the metaphorical lapels in the harbor saying, ‘Please don’t pull that net pen out — that’s the best fishing I’ve ever had in my life.’”

According to Sims, the net pen, which was free-drifting with ocean currents in waters two to three miles deep, became a great fish aggregating device. “There were tuna, there were marlin, there were mahi mahi,” he said. “This, I think, defies the conventional wisdom that fishing and aquaculture are incompatible. There are some great synergies to be had here.”

Competition and opportunities

Another major concern commonly expressed in wild-harvest fisheries about farmed fish is that aquaculture will expand supply of certain species and thereby drive all prices down. Wild salmon fisheries in Alaska are a good case study. As salmon farming became a leading segment of the global aquaculture industry, many salmon fishers and communities dependent on commercial salmon fishing expressed concern that the price of wild salmon would plummet. In short, farmed salmon, they feared, would create economic pressures in the marketplace, as it competed directly with wild salmon.

While there have certainly been struggles along the way, today we see these fears are mitigated by the fact that an overall increase in salmon supply means there is a much larger and more diverse market for all salmon products worldwide. This larger marketplace has created new opportunities for wild salmon fisheries, where a product such as wild Copper River salmon or wild Bristol Bay salmon has seen its value increase because of its own attributes. We’ve seen that in a diverse global marketplace attained largely through increase supply of farmed salmon, the two products — wild and farmed salmon — do not need to directly compete with one another as the primary mechanism for determining value. They are different products for different market segments that both can achieve a fair market value based on their own attributes.

In addition to farmed fish helping build larger, more diverse seafood markets, thereby creating new opportunities for wild fisheries, aquaculture can play a complimentary role to working waterfronts suffering from decreasing quotas in wild fisheries. In New England, for example, many fishing communities are struggling under dramatically cut quotas on iconic species like cod. Aquaculture provides an opportunity for some of these communities to diversify and create new revenue streams. Maine is leading the way in this regard, and I’m looking very much forward to covering some of these stories in the near future.

The Data are clear

So, to those readers accusing me of climbing on the farmed fish bandwagon, I say this: Aquaculture is not at odds with wild fisheries. It is not an us-versus-them paradigm. The data are clear — they show we should eat more seafood, but they also show that the sustainable supply of wild-caught fishes is insufficient to meet growing global demand.

Farming fish makes sense, when farming adheres to best management practices. It makes sense for our health, for the health of the ocean and for the health of Earth as a whole. Farming fish makes sense, but it is not to the exclusion of robust, sustainable wild fisheries. As Sims has suggested and various case studies have shown, the two can co-exist and even compliment one another, and we need to advocate for better management in both.

Image credits: 1) & 2) Kampachi Farms 3) Copper River Seafoods

Ret Talbot is an award-winning freelance science writer and photojournalist with nearly 20 years of experience covering stories from some of the more remote corners of the globe. From the icy summits of the Andes to the reefs of Papua New Guinea, his assignments have taken him off the beaten track and put his readers face-to-face with stories of adventure, new ideas and innovative approaches to commonplace issues. His current work focuses on the intersection of fisheries, science and sustainability.