Little Bets Can Have Big Impact in Corporate Philanthropy

By Anne Wintroub and Nicole Anderson

Philanthropies could learn a thing or two from comedian Chris Rock.

Rock spends months grinding through hundreds — if not thousands — of ideas from which only few will emerge as jokes for a one-hour comedy special. Those initial ideas mark a series of “little bets,” according to author Paul Sims.

In his book "Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries," Sims maintains that these little bets -- experimental, iterative, trial-and-error approaches -- gradually build up to a breakthrough, and often achieve more success than far larger ones.

He offers some compelling examples. Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin didn’t set out to develop an algorithm that radically changed how information is searched on the Internet, but to address a much smaller problem of how to prioritize library searches online for the Stanford Digital Library Project. Beethoven developed a musical style distinct from Mozart’s only after he continuously experimented and wrote hundreds of new compositions. Similarly, Jeff Bezos believes so deeply in experimentation that Amazon’s employees are encouraged to develop new ideas with the understanding that many concepts may go down “blind alleys.”

We’ve seen this little bets approach achieve big results in business, science, technology and even entertainment, so why not philanthropy? What if funders focused on enabling and accelerating these little bets?

According to Sims, this experimental approach requires the ability to fail quickly, learn fast, try imperfect ideas, and engage in highly immersed observation (e.g. carefully noting what does and does not work).

That is the idea behind the AT&T Aspire Accelerator, a six-month program designed to accelerate startup organizations -– both for- and non-profit -- with the potential to impact AT&T Aspire’s goals of helping students succeed, strengthening schools and communities, and preparing learners for employment. These organizations are our “little bets.”

Participants receive a financial investment, access to expertise, services and relationships tailored to their organization, and expert mentors from the education and technology ecosystems.

The program is based on trial and error, innovation and re-innovation. As Sims puts it, little bets require being “unshackled by constraints of conventional planning, analytical thinking, and linear problem solving that our educational system overemphasizes at the expense of creativity.” This means greater risk-taking, experimentation and failure.

Examples of these little bets include CommonLit, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving adolescent literacy through high-quality, free curriculum and advanced analytics. Through the support of the accelerator program, CommonLit developed a new suite of tools to help teachers track progress in reading and personalize instruction to better address the unique needs of individual students. These tools were offered for free to teachers and parents this September, helping to level the playing field for all students.

Another example is Couragion, the company behind an app that inspires underrepresented youth to pursue STEM careers via diverse video role models, games, quizzes and personalized learning plans. Through the accelerator program, Couragion was able to expand its technical platform support from Apple iOS to responsive Web, thereby making its app accessible to the 50 million youth that do not have access to iPads.

2015 accelerator participant GradGuru is a nonprofit whose software service and mobile app guides community college students to take actions and engage in behaviors that lead to higher and faster completion rates. While in the program they partnered with five new colleges with a total of over 125,000 enrolled students.

So much of traditional philanthropy involves making big bets to solve complex problems like poverty, climate change or infectious diseases. Yet, as Sims notes in his book:

“The top-down, procedural planning approach is highly dependent on making predictions about the future based on past experience. … The fact is that much of what we would like to be able to predict is unpredictable. … In this era of ever-accelerating change, being able to create, navigate amid uncertainty, and adapt using an experimental approach will increasingly be a vital advantage.”

Accelerators are now commonplace for many technology companies, but this model of incubating little bets is ripe for philanthropies as well. By making little bets, philanthropies can fail quickly and learn fast and they can inspire and empower what just may be the most creative and ground breaking approaches to solving our greatest challenges.

Image credit: Pixabay

Anne Wintroub is director of Social Innovation for the AT&T Foundation.

Nicole Anderson is assistant vice president of Social Innovation and president of the AT&T Foundation.

A Look Back: The Evolution of LCA and Life Cycle Impact Assessment

By Harnoor Dhaliwal

Life cycle assessment (LCA) has emerged as an important tool for understanding the environmental footprint of products and services, with inventory analysis and life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) helping to itemize and quantify environmental impacts. Although LCA and LCIA are new concepts for many outside the sustainability community, they have a remarkably long history. Here’s a brief look at their evolution, and the ongoing intellectual investment and refinement that make them such powerful tools today.

That evolution began more than four decades ago, with the earliest relevant studies dating to the late 1960s and early 1970s when emerging environmental issues such as energy, solid waste and resources were primary concerns. (Excellent historical perspectives can be found in the 2011 policy analysis Life Cycle Assessment: Past, Present, and Future, edited by J.B. Guinée.)

It wasn’t called LCA back then. The term resource and environmental profile analysis (REPA) was often applied to these kinds of assessments, which used diverse approaches and definitions. This lack of standardization and absence of a shared common framework for impact assessment made it very difficult to get reliable and reproducible LCIA results until the 1990s.

The first method to emerge as a standard LCIA methodology was CML 1992 (Guinée et al., 2002). Built with what were then state-of-the-art modeling tools, it gave us a set of 10 impact categories based on what we care about and need to protect. The CML method used models like RAINS-LCA for assessing acidification and eutrophication and USES-LCA 1.0 for assessing toxicity, and has provided a basis for subsequent advancements.

Many new methods and models have been developed since then. We saw EDIP, a Danish method (Wenzel et al., 1997). In addition to measuring climate change, ozone depletion and toxicity, it included solid waste as one of the impact categories. In 2002, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released TRACI (Bare, 2002), in which impacts are modeled in the context of North American conditions – a step that made it more attractive for U.S.-based LCA studies.

We also saw methods like Ecoindicator 95 and Ecoindicator 99 (Goedkoop et al, 1999) that introduced a new approach to impact assessment: measuring impacts at the end of the cause-effect chain. This endpoint method was created to ease decision-making by presenting results as three key relatable areas of protection, i.e., human health, ecosystems and resources. This approach was later incorporated into hybrid methods like IMPACT2002+ (Jolliet et al., 2005) and ReCiPe (Goedkoop et al., 2009), which include impact assessment at both midpoints and endpoints.

Along the way, one of the most challenging aspects of impact assessment remained the modeling of toxicity, and the challenges associated with assessing its potential impact using generic values. Actual toxicity impacts are, of course, highly location-specific and dependent upon existing background concentrations and thresholds. This discrepancy between measured impacts and actual impacts leads to great uncertainty in the results.

To make matters worse, each impact assessment method used different models, parameters and units, making it nearly impossible to compare results across different methods.

This criticism led to efforts to unify and harmonize the models. The Life Cycle Initiative, sponsored jointly by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and the Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC), engaged the developers of CalTOX, IMPACT 2002, USES-LCA, BETR, EDIP, WATSON and EcoSense in creating a consensus model that incorporates the strengths of each and provides the most robust results.

The result of this effort was the USEtox model (Hauschild et al., 2008). USEtox has since been reviewed and endorsed by the Life Cycle Initiative and was incorporated in some of the newer methods, such as ILCD 2011 (European Commission, 2012), TRACI 2.1 (U.S. EPA, 2012) and IMPACT world+ (now in a beta version).

Making impact assessment more spatially specific is another area of ongoing work. Given how geographically spread out LCA can be, developing spatially specific methods means greater complexity and a lot more data. The IMPACT World+ method attempts to address this issue by creating several regions based on an archetype approach. For example, for assessing respiratory impacts, urban and rural archetypes are used which consider population density.

Another area of big change and evolution is the treatment of water depletion – a topic that wasn’t even considered in the early days, but is now at the front and center of environmental evaluations. A milestone in water depletion LCIA came in 2008, with regionalized characterization factors at both midpoints and endpoints (Pfister et al 2009; Pfister et al 2010; Motoshita et al 2010; Berger et al 2014).

Today’s LCIA methodologies have come a long way from where they started, thanks to the hard work, patience and persistence of hundreds of researchers around the world. With an increasing understanding of the environmental mechanisms and more and better data, we are continuing to reduce the uncertainty in the results. While many aspects of LCIA need additional work and improvement, we have better tools than ever before, and increasingly reliable guidance towards more-sustainable approaches.

Image credit: Nixon Presidential Library via Wikimedia Commons

Harnoor Dhaliwal is a certified LCA consultant at EarthShift Global. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Botany from University of Delhi, India, and a Master’s degree in Environmental Policy Studies from New Jersey Institute of Technology. She did her graduate research work on sustainable remediation of contaminated sites. At EarthShift Global, Harnoor has carried out ISO-compliant Life Cycle Assessment studies on products including biofuels, packaging materials, food products, medical and pharmaceutical products, and industrial equipment. She has also developed and taught LCA courses. Her current focus is evaluating social Life Cycle Assessment and its application.

This Small Business Became Carbon Negative - And Wants to Make It Easier for You

By Robert Garza

Normally at our all-hands meetings we at Pacific Medical Training think about new CPR guidelines, getting jobs for our students or other ways we can change the world. But this time a new idea floated up: Could a small business like us become carbon neutral, and how hard would it be?

Admittedly this wasn’t very high on our list of priorities, especially considering how difficult it was to get started, and we had no idea what it might cost. But with persistence we were able to make it happen and document the whole process.

By skipping to the answers below, maybe your company can make this socially conscious change and get it done a lot faster than we did!

What is carbon, and why be neutral?

Before industrialization and through hundreds of millions of years of balance, Earth created an atmosphere that supports animals, which need oxygen, and plants, which need carbon dioxide. Basically animals breathe in oxygen and exhale carbon dioxide, and plants do the opposite. All of the natural things that happen in this world support and depend on this balance. But recently there has been a disturbing change.

Human activity generally upsets this balance. Cutting down trees, burning things for fuel, and the ways we raise livestock all add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere or remove the replenishment of oxygen. We have done these things with such reckless abandon that it is starting to impact Earth’s natural systems. Humans have a responsibility to understand their own personal contribution to this balance. And doubly so for industrial concerns, like businesses.

For more than a third-graders’ analysis on the carbon ecosystem, check out this resource from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

We don’t burn anything. How much carbon does our company use?

Short answer: A lot, but it is manageable.

Our company is a high-tech education business. A lot of the people work from home using their computers and phones, and we definitely don’t directly burn anything — at least not on purpose. But when you use electricity or commute to work, this results in carbon emissions. Luckily, it is pretty easy to find out how much.

If you are a large company and have your own metered utilities, it is dead simple to find your carbon usage. But our company is in a shared space, so we needed to do an electricity survey. Just write down the model number of everything that plugs into the wall, and look up the energy usage in watts online. (Don’t forget the lights overhead!)

We added everything up and found THE NUMBER. We would love to share this number with you. But our competitors rip off our website, copy our products and actively call us on the phone digging for information. So, we cannot tell you how many square feet we lease or how many servers we have.

This article is mostly for small business. But other calculators out there for big business can estimate the carbon impact of industry conferences and other large-scale items. Be careful: Many carbon calculator websites have buy buttons -- read the next section before clicking them!

More calculators and how to estimate your carbon footprint:

- EPA: Carbon Footprint Calculator — for individuals

- Constellation Energy: Carbon Certificates — for large companies

- EPA: Carbon Calculator — for utility usage

We emitted carbon. So now we have to stop breathing?

Don’t hold your breath.

Through a process of offsetting, your company can invest in a renewable energy or other carbon emission reduction project. The idea is simple: A bunch of people put up money (“credits” or “offsets”) and then use it to plant a bunch of trees or replace a coal power plant with a solar one. So, at the end of the day, you can still drive a car to work instead of walking, but the trees you planted eat that carbon for breakfast. And it all nets out to zero. Or in other words, you’re carbon neutral.

That’s it.

And who plants the trees for me?

This was the hardest part.

An aside: If you (more likely your parents or grandparents) have a home phone line, you probably get lots of phone calls from “nonprofits” asking for donations to save firefighters or needy children. Well, a lot of those organizations are complete scams.

When researching how much carbon we produce, we saw lots of free calculators on lots of websites. Each one ended with a 'buy' button that promised to absolve us of all our sins. But always be careful before starting a new business relationship.

First we called PECO, our local utility, to see if the company could recommend or directly sell us carbon credits. This led to a long list of transfers and redirections. I just want to emphasize that everyone was very helpful and willing to solve the problem. They even answered the phone promptly, which was a great surprise. But nobody answering the phone had heard of carbon offsets or carbon neutrality before, and said they hadn't received other calls about them.

Contacts that have never heard of carbon offsets:

- PECO customer service — 800-494-4000

- PECO business services — 800-454-4100

- PECO Montgomery County new service lines — 215-956-3270

- Exelon customer service — 800-483-3220

- Exelon marketing department — (transfer from above)

- Constellation (an Exelon company) — 888-635-0827

This is when I started taking notes and realized we need to blog about this. A second source we trust is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The agency has a page on carbon offsets, and we reviewed each carbon offsetting program it discussed. Most of them are geared toward large companies, and they promise to put your name on a specific project and provide contacts you can call to discuss your project. That is way too big for us! We reviewed each program and listed below the ones that have “buy now” buttons for small business.

- EPA Greenhouse Gas Offset Program List — our starting point

- Carbon Fund — projects all over the world for renewable energy, forestry and energy efficiency

- Colorado Carbon Fund — projects in Colorado for landfill methane capture and solar power

- Carbon Zero Canada — projects mostly in Ontario for landfill and food waste carbon recapture

You can find a local project near you. Or you can invest in decommissioning coal plants on the other side of the world. Either way, you are going to breathe that air at some time. So research these projects and pick one you can get passionate about. Or tell us about other projects you have found!

Conclusion

We looked at all the options and tried to decide among them. Then it happened. We decided to do all of them. That’s right … Pacific Medical Training is carbon negative! Technically, any carbon neutral company can just invest in one more project, and they become carbon negative. It sounds way cooler, you should totally do it.

We calculated our carbon usage, went to each of the three pages above, and signed up for carbon credits. Well, at least we tried. Then we found out that only Carbon Fund accepts American Express, so we just contributed more to those projects. We asked the other organizations to accept AmEx and look forward to supporting them in the future. Colorado Carbon Fund responded and agreed to accept AmEx. Its website has been updated.

I am sorry that we cannot give you the exact number, but I can tell you that the cost to become carbon neutral is on par with our corporate budget for beverages. So if your company consumes as much as we do, now you know how easy it is to do so in a socially conscious way.

Image credit: Pixabay

Robert Garza is a project management and web development intern at Pacific Medical Training and part-time student at the University of Pennsylvania. Robert's professional focus is on providing useful resources for medical workers and students. As a student, Robert is majoring in economic history and has a particular interest in labor and in education.

A Snapshot of CSR in Central and Eastern Europe

By Sandra Feltham

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is regarded as a universal concept based on the triple bottom line principle. But despite this widely acknowledged concept, its interpretation and popularity change over time and differ between regions. This applies not only to world regions such as the U.S. and Europe, but also on smaller scales, e.g. between Western Europe and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

Europe is the continent that first dealt with the CSR movement. Europe boasts traditionally more consistent CSR values, norms and perceptions compared to other areas of the world. European corporations tend to hold stronger and broader approaches to stakeholder relations, and that network is being established to help companies share and diffuse relevant information about CSR. Through CSR, corporations importantly contribute to the EU’s treaty objectives of sustainable development and highly competitive social market economy.

While CSR has a particularly strong resonance in parts of Western Europe, it took root slowly in Central and Eastern Europe. As the U.N. Development Program put it: "Due to the socialist heritage, there is a general perception, both in the business community and the public at large, that social responsibility and social caring is the primary role of government. Most companies consider their responsibility to operate in compliance with the legal and regulatory environment of the given country."

However, in recent years CSR a became a “hot” topic in Central and Eastern Europe. CEE countries are increasingly integrating themselves into the global political and economic system, and there is an emerging need to integrate corporate responsibility in the mainstream management education and executive education.

Western and Eastern Europe compared

Reputation remains the main focus of CSR in both Western and Eastern Europe. The main drivers for companies to adopt CSR in the CEE region is to protect brands and keep a company's ‘licence to operate’ -- society’s approval for their activities. The same is still true for many Western companies, but leaders moved on to addressing how sustainability affects the core business through innovation and strategy.

CSR (or sustainability) reporting is taking a similar route. While people in the CEE region are slowly learning how to apply it, in the West most of the companies have already managed to leverage reporting into significant benefits. Committing to CSR reporting led companies to develop their stakeholder relationships and also to improve management communication systems. One of the notable benefits was the setup of public commitments, which assisted companies in moving forward. Now, the new systems have worked into the company culture and yearly reports do not require extra effort.

In the CEE region, most of the big players are subsidiaries of multinational corporations normally headquartered elsewhere. Such subsidiaries are applying centrally managed CSR, customized to local laws and regulations. Only some would take the opportunity and make this process a competitive advantage.

The other issue is starting a conversation about any type of government intervention; the legacy of communism is vividly remembered. It has to be clear governments should limit the use of sustainability promotion policy measures through market devices not through direct planning. Although, the stance on whether CSR should be regulated or remain voluntary is equally mixed.

Data from the Czech Republic

Our CSR agency is based in Prague, Czech Republic, which is one of the leading countries in the area of sustainability in the CEE region. Many businesses still refrain from setting up their own CSR programs, usually citing the fear of increased costs, lack of time and human resources, lack of motivation, and insufficient knowledge of how to set up and apply a CSR strategy. Similarly, there are still some businesses that understand CSR as a false promise or an empty PR strategy rather than an inherent part of their corporate identity, although this trend is now luckily diminishing.

In 2016, research conducted by Ipsos showed that while consumers care about whether a product or service is provided under ethical conditions with regard to environmental conservation, their theoretical knowledge of CSR is not as widespread. According to the research, the public still wants companies to communicate ethically, focus on environmental friendly products and services and secure the safety of their employees.

Currently, phenomena such as fair trade, environmentally friendly products, farmers markets, social enterprises or organic farms demonstrate that products made in the context of ethical business and produced in a sustainable way are not only appealing, but also bring social benefits and are economically profitable. And thanks to the successful CSR case studies that have happened in the West, it is now only a matter of time before this concept will be fully applied also here.

Image credit: Flickr/Roman Boed

Sandra Feltham is Founder & Director of Flagship Consultancy - first specialized consultancy in the CEE focused on corporate sustainability strategy and non-financial reporting. Sandra is a leading expert on corporate sustainability strategy and sustainable development in the Czech Republic.

The future of power, death & money

Talking About Race and Police Violence at Work

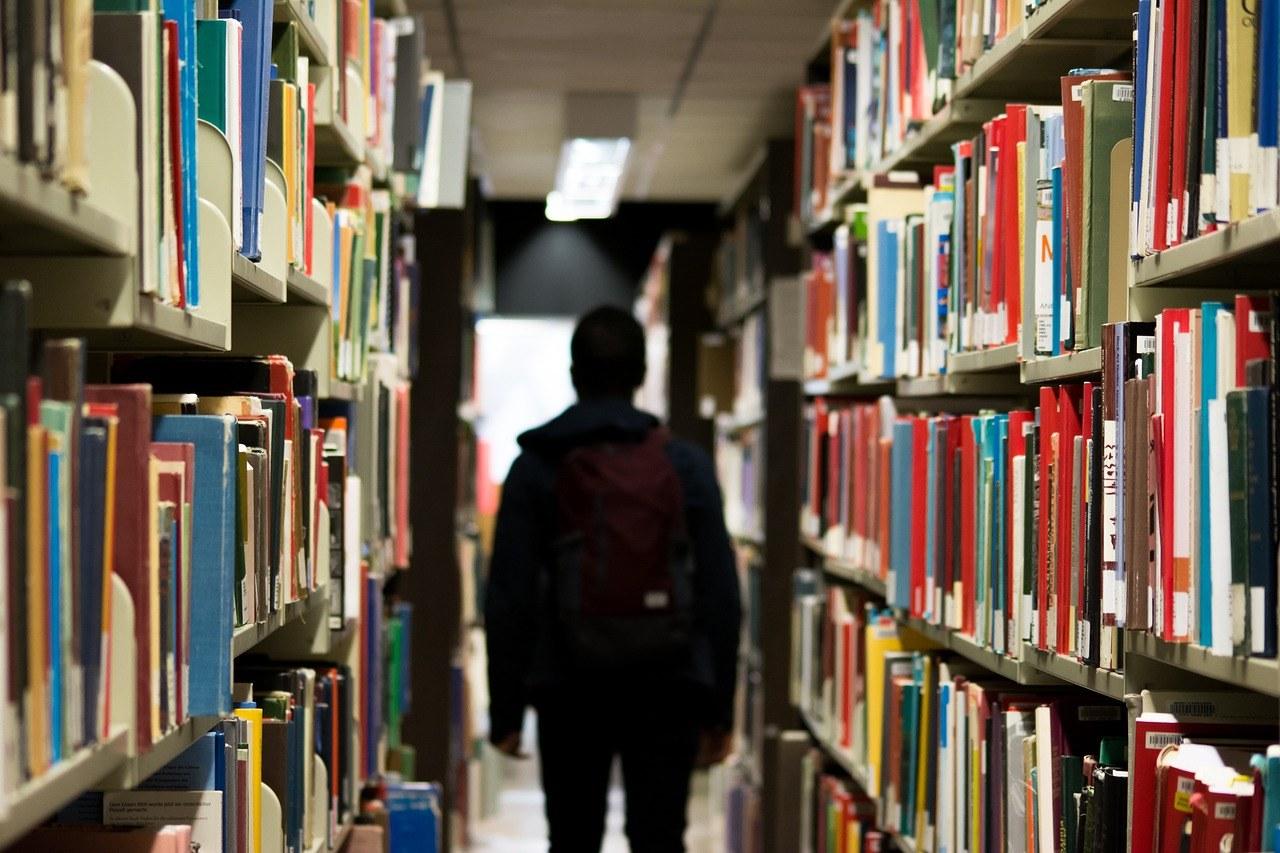

A total of 816 people and counting have been killed by police in the U.S. this year. That number is increasing at an almost daily rate, according to information culled from an open-source database established by the Guardian newspaper to track fatal police shootings around the country.

The impact of these murders has been thoroughly expressed within affected communities, across the news cycle, and rooted within the deluge of op/eds written by black community leaders sounding off about the state of emergency on black lives.

Unfortunately, most of corporate America remains mum on said emergency. Reasons vary, but the silence is strange given corporate support for other social issues such as the LGBT community's quest for equal rights and elimination of the gender pay gap.

Those hardest hit by the silence may be those at home: minority employees who do not have the luxury of sharing their thoughts and feelings without the fear of being ostracized, silenced, or potentially putting their job in jeopardy.

In a heartfelt open letter following the killings of several black men, Mandela Schumacher-Hodge (who is a black woman) wrote passionately about her very first experience having her boss (who is a white woman) speak up on these surmounting issues.

“When I went into work yesterday, the first thing my boss, who is a White woman, mentioned to me was the anger and pain she was feeling about the fatal shootings of two more Black men by White police officers,” wrote Schumacher-Hodge, portfolio services director for social impact investment firm Kapor Capital.

When asked why her employer’s open dialogue about race and the subsequent killings of black men was significant to her, Schumacher-Hodge adds that not one of her previous employers or colleagues broke the silence to discuss how she or any other employees of color might be feeling in the wake of national tragedies.

The article, written in early July, offered several straightforward tactics white colleagues can implement to help support colleagues of color:

- Educate yourself

- Talk about it

- Give people space

- Take action

- *Keep* looking in the mirror

Readers took that advice to heart. The letter fueled an onset of outreach from Schumacher-Hodge’s former colleagues who apologized for never thinking to ask her about how she was feeling. A few simply claimed they weren’t sure how to bring it up or even how to start the conversation. That's something Freada Kapor — Schumacher-Hodge’s boss and company founder — admits must drastically change if the work environment is to ever truly be a space for everyone to fully be themselves.

Kapor is also the founder of the Level Playing Field Institute which promotes innovative approaches to fairness in higher education and workplaces.

“We need a new norm," Kapor says. "You can’t be a decent boss unless you create an environment about what’s going on in the world and how it impacts [people] coming into work every day."

“People have the right to have their experiences and thoughts and to express them to the point that they are not being uncivil or disrespectful to others. People who are marginalized [in this country] are usually silenced in society.”So, how does leadership cultivate a safe environment where employees can have an open dialogue about the state of affairs without fear?

Kapor prescribes creating a culture of diversity and inclusivity by physically creating safe spaces and then starting the conversation at the top.

For example, Kapor and Schumacher-Hodge point to the signals riddled throughout Kapor Capital’s San Francisco headquarters indicating the environment is a safe space to have emotional conversations. Black Lives Matter signs are posted on the windows and sentiments about what’s going on in the world remain highly visible. Staffers also use email exchanges to share content and resources on a variety of topics to facilitate these important conversations.

Kapor also points to the makeup of the firm: A majority of its portfolio company's CEOs are people of color, and leadership staff is also very diverse. That's in stark contrast to most corporate environments, particularly in the Bay Area's massive technology industry where black and brown people represent less than 3 percent of employees.

This diversity, Kapor says, makes all the difference when it comes to willingness to discuss race in the workplace. LGBT issues come to light the first time a favorite cousin brings his boyfriend to Thanksgiving, and gender equality takes on new meaning when a daughter hears offhand insults in the workplace. But many executives lack a frame of reference when it comes to relating to people of color. That means they must be intentional when it comes to fixing the problem.

“I think it is a complete and utter lack of empathy and reflection of how separate we are by race in this country,” Kapor explains. “White Americans live in a bubble and don’t have a real opportunity to interact in real ways with people of color that will give us a basis for empathy.” Thus, a police officer murdering a black man registers a closeness for people of color -- they realize the next person transfigured into a hashtag at the hands of a police officer could very well be their fathers, husbands, brothers, nephews or sons.

Contrastingly, white people without close ties to people of different races can show apathy through inexperience. That can be extremely detrimental as it translates into discriminatory policies throughout society and police held unaccountable for racially motivated killings. As a minority in the workplace, it doesn't surprise me that a person of color might choose to stay silent.

Kapor's firm holds listening tours and trainings for CEOs, particularly the white males, who have directly asked for help having conversations on race and diversity.

“It’s our responsibility to educate ourselves and other white people, especially those in power,” she says. “It’s not our job to delegate [the responsibility of diversity] and ask others to clean up the mess we made.”Image credits: 1) Flickr/niXerKG 2) and 3) courtesy of Kapor Capital

BP's Failed Attempt to Go 'Beyond Petroleum'

The following is an excerpt from a newly released book from the former CEO of BP, called "Connect: How Companies Succeed by Engaging Radically with Society." It has been condensed for readability in blog format.

By John Browne, Robin Nuttall and Tommy Stadlen

In 1997 I was the first big oil chief to acknowledge the link between man-made carbon emissions and global warming.

I believed that oil companies, or at least BP, could no longer deny the problem. Something had to be done. But while my belief came from the heart, the last thing I wanted admit at that point was that it came from anywhere but my head. The board, executive team and employees had to be persuaded that BP was not about to commit commercial suicide. Taking a stance on climate change could make the company a sitting target for NGOs and competitors alike.

While American oil majors railed against BP for exposing the industry to environmental regulation, NGOs voiced concerns that the company was not going far enough. Some, such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, refused to countenance anything other than a complete replacement of the world’s hydrocarbon system.

It was extremely hard to engage them in productive debate because their starting point was that BP should not exist. Others, such as the Pew Center and the Environmental Defense Fund, were more realistic but still nervous that my 1997 speech was little more than ‘greenwash’. BP worked hard to win their trust and eventually forged excellent working relationships with both groups. They wanted to make sure the company’s actions were meaningful, and BP needed their expertise to make that happen. Fred Krupp, the long-standing head of the Environmental Defense Fund, played a central role in the creation of the emissions trading scheme. In the 1970s his organisation had successfully halted the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline; now, twenty-five years on, Krupp was working at the heart of BP as it sought to fix its relationship with the environment.

None of this was easy. It took a lot of senior-management time, required investment and demanded a large exercise in external engagement. But BP also achieved tangible impact in the battle against climate change.

At Stanford, I announced a target of a 10 per cent reduction in carbon emissions based on the 1990 baseline, to be achieved by 2010. BP reached this goal in only four years, saving $650 million in the process, by tightening up valves, halting the venting of gas and improving energy efficiency. This was low-hanging fruit that the company had ignored until the climate programme focused minds and provided the right incentives. Quick wins helped to generate momentum and build belief in the strategy amongst the workforce.

At the centre of the carbon savings was the emissions-trading scheme. Beyond its direct impact on pollution, the development of this market-based instrument also helped BP win a seat at the policy table. When the UK government wanted to develop its own cap-and-trade system, it came to BP for advice. Today, emissions-trading schemes are a crucial plank of climate-change policy across the world. The Clinton administration also began to view the company as a trusted adviser on global-warming solutions, as did California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Most importantly of all, BP changed the debate on climate change. With Shell, it led the oil industry from a position of vehement denial to an acceptance that the status quo was unsustainable. Today every international oil company acknowledges man-made climate change. Instead of arguing with the energy sector over the science, governments and NGOs can now concentrate on working with industry to develop solutions. It was this realisation that Big Oil must move towards a low carbon world that motivated me to change the firm’s tagline to Beyond Petroleum.

In hindsight this went further than the public could then accept. It was a mistake to push so hard. Beyond Petroleum should have been a subheading, not a main line. The renaming symbolised the shortcomings in our climate strategy. In essence, the company had got ahead of itself and ahead of where industry and government were willing to go at that time. Beyond Petroleum was never meant to be literal – not yet, anyway – but there was still too much of a gap between the aspiration and reality, which I now regret. The actions we took were bold, but they could have been bolder. Ultimately that was my fault, and the barriers I failed to overcome provide a useful lesson for today’s CEOs as they attempt to change the status quo.

It became exceptionally difficult to keep up the pace of progress. When it became obvious that the race was on to succeed me, some saw an opportunity to moderate the firm’s position on climate change. Others sensed a growing hostility to environmentalism among right-wing voters in the US and lobbied hard to stifle coverage of BP’s actions.

In other areas BP was let down by government inaction. When environmental protection requires companies to incur costs, it is up to the state to introduce regulation that creates a level playing field and stops free-riders taking advantage of firms that invest voluntarily. After twenty years of failed UN conferences, governments are still unable to agree an international treaty on climate change. That is not an excuse for business to sit on its hands but it certainly makes it harder to justify investments to lower carbon emissions. BP did allocate time and money for research and development on carbon capture and storage but did not receive sufficient backing from the US or UK to make it an economically viable option. Like Shell, BP was willing to share the results of any breakthrough as a public good, but needed the state to underwrite part of the significant costs.

My developing view of climate change at BP demonstrated why the environment is the most difficult stakeholder of all to connect with effectively. Society was no longer willing to tolerate denial of climate change but neither was it ready to create a context that rewarded a full-blown attempt at a solution. To understand that paradox we need to look to the past.

John Browne, chief executive of BP from 1995 to 2007, is now executive chairman of L1 Energy.

Robin Nuttal, partner in Mckinsey's London office and Tommy Stadlen, Tech entrepreneur, co-authored this book.

Theranos, 23andMe and Zenefits: Why Medical Startups are Still Struggling

Startup opportunities seem endless in the digital age. From a website connecting consumers with garage sales in their own cities, to platforms that streamline the way enterprises monitor and manage their cloud infrastructure, the overnight business sensation for which Silicon Valley has come to be known is far from over. Last year, Inc. magazine featured 53 young companies that were due to take the economy by storm. While not all of them made the cut, those that offered concrete but ingenious support for things like data management seemed to fare well. So have companies that offer actionable ideas, like ways to spruce up your interior decor or make great recipes.

What you generally won't find in this year's list of blockbuster startups are scores of innovative, break-the-mold healthcare companies. Companies like Theranos, whose minimalist outlook toward blood testing was at one time, touted as the evolutionary stage for a $75 billion industry. Or Zenefits, which reportedly offers easier ways to manage employees' healthcare benefits. Or the host of do-it-yourself testing companies like 23andme that offer genetic testing by mail. Each one of these models offers the market (either to the consumer to client businesses) a never-before seen approach to a common healthcare demand. And all three of these companies were confident that the path they were carving out for themselves would not only create blockbuster success, but help redefine medicine as we know it.

But would the medical field, and the US regulators be ready for them?

Theranos, 23andMe and Zenefits: the venture capitalist's dream

There was a time when Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes' vision seemed unassailable. The 19-year-old Stanford dropout founded the company in 2003 with the aim reportedly to democratize healthcare and bring the cost -- and the method -- of blood testing down to an affordable level. Her aim wasn't entirely altruistic. Lower cost would mean more people would be willing to be tested for health risks before they became sick. It meant impoverished communities would have quicker access to testing as well as treatment, minimizing the cost of healthcare in general. And it meant a more efficient healthcare industry.

Her vision was to revolutionize the way blood was obtained by developing a method that would extract blood from the finger in small amounts instead of from the arm. To healthcare workers dealing with natural disasters where sterile environments and a full array of testing equipment are rarely available, developing a hand-held device that took blood from the finger, required a smaller sterile field and less patient stress was a long overdue innovation.

For venture capitalists, it was a godsend as well. Valued at $9 billion (there are some who dispute this valuation now), the company touted an almost fail proof concept: lowering blood testing costs by even 0.8 percent could save the healthcare industry almost $100 billion in overhead in the next decade. How could a product like that not work?

For Parker Conrad, Zenefits' founder and ex-CEO, a cloud-based software company that helps employers navigate the often complex world of human resources management made sense as well. Conrad made his entry into the HR management field in 2013, just as the Affordable Care Act was gaining ground and companies were struggling to understand the regulations.

In the first few years of its very short rise to fame the company investments paid out and paid out well. By 2015, the company's value had risen to $4.5 billion and its services were gaining a footing in both in California and New York, while expanding across North America.

Genetic research into diseases like Alzheimer's and Multiple Sclerosis has propelled the growth of companies like 23andMe. With the genetic testing industry slated to grow almost 10 percent in the next five years, a testing system that allows individuals to order a genetic profile by mail made sense to founder Anne Wojcicki. Instead of driving across town to a lab, clients simply spit into a vial and mail the sample back for analysis. It's not hard to see how a testing regimen that can scan for hundreds, if not thousands of genetic mutations could have tremendous revenue potential as genetic research continues to grow. Now in its 10th year, 23andMe has a valuation of $1.1 billion. Small, compared to Theranos and Zenefits, but packed with potential.

Disruptive companies vs. the feds

There's a reason that successful startups are often coined disruptive companies. They make waves, and they create change.

But what happens when the industry you are attempting to break into is governed by privacy regulations that determine what can and can't be sent to a patient or client? In November 2013, 23andMe was ordered to discontinue consumer access to its health-related reports due to concerns by the Food and Drug Administration that it hadn't met regulatory requirements related to medical testing and diagnosis. According to Wojcicki, the issue was due to a mixup, and you can read the company's official statement here. According to the FDA, it was noncompliance: 23andMe hadn't met the requirements to operate, and the fact that the company would be issuing detailed test results that could be interpreted as medical advice sent off warning bells for regulators. 23andMe eventually resolved the confusion, but the message was clear: Even startups had to jump through regulatory hoops in order to operate. Even disruptive companies had to meet compliance.

The Theranos story is more complex and circuitous, but arrives at the same conclusion: Companies that challenge the conventional path to success are great for Silicon Valley's tech industry, but problematic for sectors that delve into more personal arenas like medical testing. In October 2015, Wall Street article reported that Holmes wasn't being entirely truthful about the accuracy of her products. The investigation included statements from former staff that said Theranos' labs were practicing unsafely and were skirting federal regulatory procedures. Later that year Theranos announced that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had visited one of its labs and subsequently banned Holmes from operating a medical testing lab for two years. It also imposed a monetary fine of undisclosed amount. Lawsuits from patients saying that they were duped by faulty equipment have been filed as well. It may take Holmes longer than two years to weather the effects of this controversy.

Critics maintain that accuracy and transparency are at the heart of the debate over whether Theranos should be allowed to operate. Advocates of the company -- and there are many -- maintain that it's more a fight about industry dollars: what will happen to the wealth of the industry if Holmes does succeed in slashing medical costs. Politics and controversy, one investor acknowledged, are sometimes the bi-product of a successful disruptive company that has the potential to up-end a market.

Still, Holmes does admit that her brand-new technology is still in development stage and may need more tweaking. But the benefits that will emerge from technology that is so small it can take a blood sample from a premature baby the size of your palm, she maintains, is worth fighting for.

When it comes to Zenefits, it's hard to fathom how a well-respected and fast-growing brokerage firm with a yearly recurring revenue of $100 million could fall from grace so quickly. But by the time Conrad had been forced to resign as CEO, the three-year-old company had already wracked up millions of dollars in state fines and was fighting for its life. Conrad, a programming whiz, had unwisely devised a macro that would allow staff to bypass state training courses that were required in order to gain a broker's license. The macro effectively allowed 80 percent of its staff to sell insurance packages without being licensed. It also prompted multiple state investigations and nearly forced Zenefits into bankruptcy.

On the surface, it would be easy to blame Zenefits' fall on hasty decisions and the naive assumption that a startup is somehow exempt from the regulatory demands of the industry. But Zenefits' early encounters with the state of Utah's regulatory arm suggests that the company's real problem was lack of preparation. It assumed that state regulatory agencies would allow the company to market its products. Instead, it found itself locked out of the state of Utah when the state insurance department (incorrectly) labeled its free software as a rebate gimmick, which state law prohibits. The company also didn't investigate to make sure that state insurance offices across the country would be able to use the software it was offering.

But the real question may be whether federal and state regulatory agencies are prepared for business ventures that promise to deliver in record time and have the venture capital to prove it. Do they have the mechanisms in place to support healthcare enterprises that are out to improve ailing delivery systems and boost technology? With an aging population that is expected to outgrow its younger cohorts in the next four decades, developing state and federal regulatory frameworks that can meet the innovative healthcare companies of tomorrow may be the country's greatest disruptive challenge.

Image credits: 1) Flickr/TechCrunch; 2) Flickr/TechCrunch; 3) Flickr/Dennis Crowley

Study: The World's Reservoirs Release More Methane Than All of Canada

According to a Washington State University study, the world’s reservoirs create more greenhouse gases than all of Canada. The paper, to be published this week in the journal BioScience, also found that reservoirs in particular contribute a large portion of the world’s methane emissions, a greenhouse gas the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suggests is 28 to 36 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The amount of greenhouse gases from all of the globe’s reservoirs could be as high as about 1 gigaton, or about 1.3 percent of all emissions generated by human activity.

The study could roil the global hydropower sector, a provider of as as much as 16 percent of the world’s electricity, as many of the world’s reservoirs store water before it flows through a turbine. The U.S. alone is home to over 1,600 of these hydropower installations, which supply power across all 50 states.

Although it may not be obvious to people who have long enjoyed reservoirs for the recreation options they offer, scientists have long known that reservoirs release a significant amount of methane. In contrast to bodies of water that formed naturally over time, reservoirs have often flooded areas that contained massive amounts of organic matter. Hence the methane “bubbling” that researchers say is the cause of these emissions. Add the fact that many reservoirs are the receptacle for materials such as phosphorous and nitrogen which flow in from rivers and streams, and the result is that these bodies of water become generators of nitrous oxide, carbon dioxide and methane. Now the Washington State study posits that reservoirs emit 25 percent more methane than scientists previously thought.

The research also challenges the conventional wisdom that reservoirs in tropical areas emit more greenhouse gases than those in colder climates. The scientists who worked together on this study concluded that a reservoir’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions depends on how biologically active it is, as algae and other organisms are behind the release of methane gas.

Whether this study moves the needle on global debates centered on climate change, sustainable development and renewable energy remains to be seen. Countries invested in hydropower for decades as it supplies citizens and businesses a cost-effective means to generate electricity – and now it is seen as a key to ending dependence on fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas. Then there is the social benefit of reservoirs, as they offer many citizens opportunities to enjoy the outdoors.

But if any “winners” from this study had to be named, there are definitely two groups vested in the global water industry that could benefit in the long run. First, proponents of aquifer recharging, a process that must scale if the world is going to be able to supply reliable sources of water for citizens. In addition, proponents of desalination technology -- a process that's now an energy hog but has the potential to become more sustainable -- will want to point out that coastal areas will need to rely on this source of fresh water as space for future reservoirs will come not only with a huge financial cost, but possibly with its own environmental price tag as well.

Image credit: California State Parks/Flickr

What California's History-Making Climate Laws Mean For Emissions Policy

By Chris Busch

California fortified its role as a global leader in climate policy with the passage of Senate Bill (SB) 32 and Assembly Bill (AB) 197. On Sept. 8, Gov. Jerry Brown signed these bills into law, establishing a new ceiling on emissions in 2030 under SB 32 – 40 percent below 1990 levels – and new rules guiding regulators on how to accomplish emission reductions.

While these new laws clearly demonstrate California’s unprecedented ambition to decarbonize its economy (more so than any other jurisdiction in the Western Hemisphere), SB 32 and AB 197 also raise questions about their implications for California’s cap-and-trade system. As Ethan Elkind, director of the Climate Change and Business Program at the University of California contends, "The passage of AB 197 makes the future of the [cap-and-trade] program even more murky." In fact, it is highly likely cap-and-trade, with some changes, will be enabled under SB 32 and AB 197.

AB 197 requires the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to prioritize local emissions reductions, and sets out a new analytical frame accounting for social costs, defined to include the impacts to public health and environmental risks, as well as energy system costs that are commonly included in cost-effectiveness measures. AB 197 states CARB shall prioritize direct emission reductions (specifying a particular reduction at a specific source) within California’s largest polluting sectors.

In a sense, these direct emission reductions are the mirror image of a cap-and-trade program, which establishes a market signal — the price of an allowance — and allows decentralized actors to respond flexibly using knowledge of their own facilities. Policy analysis will show that that cap-and-trade, with some modifications, helps overall program cost-effectiveness even when a broader social cost approach is used.

One change that would be required involves offsets — credits from emission reductions projects outside the sectors directly covered in California’s cap-and-trade program. So far, the majority of offsets have been sourced from outside of California.

The rationale for the inclusion of offsets as part of the cap-and-trade program has been the necessity of avoiding unacceptably high decarbonization costs. However, given consistently low allowance prices, it is hard to justify the lost co-benefits that come from sending money from California’s capped entities to fund out-of-state projects that generate offset credits. Low allowance prices are a signal California has not yet begun to exhaust the supply of in-state low-cost emission reduction investments.

A likely outcome under AB 197 is the introduction of new conditions before emitters in California would be offered these offsets as a compliance option. In this scenario, allowance prices would have to reach some price threshold much higher than the auction price floor before they would be allowed into the system.

SB 32 and AB 197 also leave unresolved questions surrounding auctioning authority after 2020. Even without auctioning, cap-and-trade can continue with free distribution of allowances. The best approach to this would be to distribute permits to people and provide them an easy mechanism to enter these into auctions — run by CARB, or perhaps by a third party — where polluters can acquire them from the public.

The prognosis for the planet just got measurably better with the adoption of SB 32 and AB 197. California has a bold new target and CARB has all the authority it needs to do the job.

Image credit: Flickr/Håkan Dahlström

Chris Busch is the Director of Research at Energy Innovation, where he leads the firm's work on California climate policy programs. His work has helped shape the state’s cap-and-trade program design and a successful set of the state’s 2030 climate policies. In spring 2015, Chris wrote a report recommending the state set a 2030 emissions reduction target of 40 percent below 1990 levels, a target later adopted in Governor Brown’s Executive Order. Chris evaluated California’s current climate strategy—a broad spectrum of performance standards overlaid with a carbon price—concluding it is working well and should be extended to 2030. Prior to joining Energy Innovation, he served as Climate Economist with the Union of Concerned Scientists, Policy Director for the Center for Resource Solutions, Policy Director for the BlueGreen Alliance, and Senior Research Associate at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Chris holds a Ph.D. in environmental economics and a master’s degree in public policy, both from the University of California, Berkeley; and received a B.A. in economics and history with honors from the University of Pennsylvania.