In a Step Forward for Oceans, Obama Expands Largest Protected Area on Earth

On August 26, President Barack Obama approved the expansion of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument, known in Hawaii as Papahānaumokuākea, to 582,578 square miles. The protected area, lying in the outermost stretches of the Hawaiian chain that extend 1,200 miles northwest of the island of Niihau, is now quadruple the size of what it was before Obama’s announcement.

Marine biologists hope this expansion helps preserve some of the world’s most pristine coral reefs and marine ecosystems where new species are frequently discovered. Papahānaumokuākea's natural wonders include a deep-water black coral reef approximately 4,300 years old and an underground mountain that rises 13,800 feet from the sea floor – taller than Hawaii’s highest point, Mauna Kea.

This expansion is a huge leap forward for the preservation of the world’s oceans. The seas provide an economic lifeline for many of the world’s poorest citizens but are under threat from the double-whammy of overfishing and climate change.

The preservation of this region started during Theodore Roosevelt's presidency after the U.S. annexed the Hawaiian Islands in the 1890s. Roosevelt enacted protections in order to stop the unfettered slaughter of seabirds including the albatross, the feathers of which were coveted for women’s hats. Over the years four other U.S. presidents increased conservation and protection measures for this region, which is visually striking with its turquoise waters jeweled with volcanic lava formations.

Then, in a surprise political move a decade ago, President George W. Bush designated these islands and the immediate surrounding waters a national marine monument. Bush’s landmark, or shall we say, watershed, moment was the first time in U.S. history that a large area of oceans was transferred to the protection of the U.S. National Park Service, which for over a century established national parks and monuments on land.

But despite that protection, estimates suggest that only about 3 percent of the world’s oceans have been protected for conservation purposes. Many scientists insist that the amount to be conserved should be at least 30 percent worldwide in order to to safeguard biodiversity, allow fisheries to replenish, and ensure sustainable development for the citizens who rely on the oceans for their economic security. The United Nations’ Convention on Biodiversity pledged to set aside 10 percent of the world’s oceans for preservation by 2020.

And Hawaiians are leading grassroots efforts to promote the idea of such an expansion. A group representing Native Hawaiians proposed the idea to the White House in January. Papahānaumokuākea is a spiritual place to many Native Hawaiians, as traditions link the long chain of atolls to gods and places where people’s spirits return after death.

This move by the U.S. should inspire other countries to follow suit. Over the past 18 months more ocean territory was designated for protection than at any other time in history. Joining the U.S. on these efforts are countries including Chile, New Zealand, Palau and the United Kingdom. Such efforts will be discussed at the annual Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), which is hosting its annual meeting this week in Honolulu, the first in the U.S. in its 68-year history.

One effort that should inspire other countries to study, and then protect, their oceanic territory is a recent 25-day expedition led by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In late May, NOAA started one of the most extensive studies of Papahānaumokuākea. The team of researchers’ scope included old-growth coral forests; albatross nesting grounds at iconic Midway Island, the scene of the battle that changed the course of World War II’s Pacific Theater; and algae growths already underway due to the effects of climate change and ocean acidification. Some of this group’s research findings and photographs, which concluded this June, are on display at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu.

Several organizations offered logistical support for this effort, including the Pew Charitable Trusts. The Pew’s Global Ocean Legacy campaign partnered with Native Hawaiian groups, local businesses, marine scientists, elected officials and environmental NGOs to make the case for Papahānaumokuākea’s expansion. Projects included studies of the region’s cultural and scientific significance, seminars, community meetings, and a media campaign. Over 1 million people in Hawaii and across the U.S. sent letters or signed petitions in urging the Obama administration to support the expansion.

“With our oceans warming and acidifying, Papahānaumokuākea will be a climate refuge where ocean life will have a chance,” said Matt Rand, director of Pew’s Global Ocean Legacy Campaign. “This historic announcement of Papahānaumokuākea as the world’s largest marine reserve is a symbol of hope that we can change course and protect the health of our planet.”

The White House decision to expand Papahānaumokuākea is one of the largest steps taken by this administration to expand the amount of U.S territory set aside for conservation. But this move has social impact as well. President Obama designated the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) as a co-trustee of this massive marine monument, a move that allows Native Hawaiians to have more influence on how the monument is managed. “This has been a 10-year effort to achieve this position,” said Kamanaʻopono Crabbe, CEO of OHA, in a written statement. “This success marks the beginning of a new era of collaboration for the co-managers of the area to fulfill the tremendous responsibility of protecting and caring for this sacred place.”

Preserving the world’s oceans will improve quality of life for people who rely on them for sustenance and economic opportunities. These same people were careful stewards of these waters for generations, and have no control over externalities such as climate change or the massive ocean trawlers that devastated fisheries. But if other countries commit to such protection at the scale of what the U.S. just accomplished, the odds that the oceans can heal and help sustain the world’s population improve.

More protected areas mean that more occasions will exist to study these complicated and fragile ecosystems. And that, in turn, can encourage civil society, governments and business to develop new strategies for managing this precious resource so they can help ensure their long-term viability.

Image credits: NOAA

Disclosure: Asia Pulp and Paper (APP) is funding Leon Kaye’s trip to Hawaii to cover the IUCN Congress. Neither the author, nor TriplePundit, were required to write about the experience.

Smartphones Are a Lifeline for Refugees, and NGOs Are Responding

An estimated 85,000 refugees will resettle in the U.S. this year. Many of them will have to balance the painful separation from loved ones with tasks such as searching for a job, finding housing and setting up a bank account.

One item that has become a necessity, even a lifeline, is a smartphone. Images of Syrian refugees taking selfies after making that treacherous trip from Turkey to Greece sparked plenty of angst among Europeans and Americans, with many trying to reconcile those images with assumptions that all refugees are poor with the clothing on their backs in tatters. Faux outrage over Syrian 20-somethings appearing "happy" upon landing on Greece’s shores led the United Kingdom’s Independent newspaper to publish an article last year explaining that it is not just affluent Westerners who tote around a cell phone.

As the World Bank explains, the cheapest smartphones can prove to be valuable for those escaping countries including war-torn Syria and Iraq. Messaging services like WhatsApp can make it easy for families to communicate. GPS and map apps can give refugees an idea of where they are, whether they are making that treacherous trip across the Mediterranean by boat or they need to find a safe place to stay in Europe.

Furthermore, this technology can make settling in a new country easier and even cheaper for nonprofits and government agencies. To that end, more NGOs found that programs which help new refugees from Afghanistan, the Middle East and Africa secure a cell phone can help make building a new life far more seamless.

The Oregon chapter of Catholic Charities, for example, has long helped resettle refugees in the greater Portland area. As explained in a recent CNET report, a retired Intel executive involved with the NGO worked with local retailers to procure cheap and discounted Android phones while convincing wireless and broadband providers to offer access for refugees for at least a few months. Another nonprofit in North Carolina seeks volunteers who can advise resettled refugees on how to purchase a smartphone, with suggestions on how to find the cheapest services while avoiding expensive two-year plans to eliminate any financial risks.

According to many nonprofits, the reality is that a smartphone is not an indulgence, but a key to communicating with loved ones abroad while integrating into new homes in the U.S. The feedback community volunteers often hear is that refugees prefer to secure a smartphone long before thinking about purchasing a car. And of course, we all know that that there are plenty of apps out there than can help consumers vet and purchase a used car when that time comes.

Friends and family still abroad also have options. GeeCycle, for example, seeks unwanted smartphones after consumers upgrade to a new device. The social enterprise provides those interested in donating old phones with a free shipping label. The devices are then shipped to Greece, and distributed to refugees so they have a way to keep in contact with the outside world and maybe even learn about the events going on around them while they seek a path to freedom.

Some needs that smartphones can provide, such as banking apps, money transfer services such as Wave and even job search sites like Indeed, are obvious. But the fact is: These small devices could offer even more potential for people who escaped the ravages of war and are now living between two very unsettled worlds. Last fall, a London hack-a-thon organized by the social enterprise Techfugees brought together programmers and engineers to discuss potential apps refugees could use, such as programs that could document war crimes or apps that assist in reuniting families. The result is that a device often seen as a luxury is now a tool that can provide much-needed emotional and logistical support.

Image credit: World Bank

Water Security Projects in Colombia Help Protect 10 Percent of the Earth's Species

The water that accumulates in Colombia’s Andes Mountains provides fresh water for 75 percent of the country’s 47 million people. That water is also the life source for over 1,800 birds and 2 million species of flora and fauna. The incredible variety of plants and wildlife is why Colombia is ranked by most researchers as being within the 10 nations richest in biodiversity – or what some scientists even describe as “megadiverse.”

One environmental NGO, Rare, estimates that Colombia hosts approximately 10 percent of the world’s biodiversity. Yet water scarcity threatens quality of life for millions of Colombians, as well as the country's wildlife.

To that end, Rare embarked on several programs that aim to increase the country’s water security. And if these initiatives succeed, Rare and other nonprofits working in Colombia can show how this country, larger than the U.S. states of Texas and California combined, can lead on sustainable development and even the development of eco-tourism.

Rare’s efforts are centered in Valle de Cauca, a department (similar to a province or state) on Colombia’s central Pacific coast that is home to over 4.5 million people. Much of Valle de Cauca’s economy is dependent on agriculture, including sugar cane, coffee and commodities such as cotton and soy. The products grown here in part fuel the economy of the local capital, Buenaventura, a port city of 350,000 through which 60 percent of Colombia’s exports leave the country.

But the increasing production of these crops, and the surge of large industries such as paper and building materials, have increased water stress across the region. Rare’s goal is to implement water conservation practices that do not just serve an environmental purpose, but also become everyday practices amongst urban citizens, businesses and farmers.

In order to pay for these water conservation and remediation projects, the NGO will partner with Valle de Cauca’s environmental agency in convincing local businesses to contribute money to a local fund. Those monies in turn are distributed to farmers in the countryside so they can build fencing or adopt more sustainable farming practices. The results ensure that the water eventually flowing downstream is cleaner and more consistent, critical to Valle de Cauca as 80 percent of its people live in cities and towns.

The partnership between local regulators, water utilities and business is a win-win: Farmers benefit financially from becoming better stewards of the land, and businesses and residents can access to cleaner water. Valle de Cauca’s local government is also tackling other projects, including ensuring the region’s aquifers continue to serve as reliable sources of clean water.

Ensuring reliable sources of water ensure Valle de Cauca’s natural wonders can thrive, which also offer local options for employment as more citizens embrace sustainable economic development. After years of political turmoil, Colombia is safe and has long been ready to embrace visitors. This region showcases plenty of natural wonders, including the country’s newest national park, Uramba Bahía Málaga. The park is rich in mangroves and other marine ecosystems to which humpback whales from Antarctica migrate annually. A cleaner environment also ensures the way of life for citizens in remote villages such as San Cipriano, where largely Afro-Caribbean residents live surrounded by water pools and a wide variety of tropical birds. Even mainstream publications such USA Today are tout Colombia’s travel potential.

Efforts such as those launched by Rare offer hope that Colombia’s economic development can continue fairly for all while preserving an important part of the world’s biodiversity.

Image credit: Rare/Jason Houston

7 Tips for Compelling Communications About Sustainable Agriculture

By Aaron Pickering

In Louisiana, a farmer continues her father’s legacy of growing quality rice, making a living by producing a key ingredient for breakfast cereals enjoyed around the world. Meanwhile, in Sierra Leone, 5,000 smallholder farmers have been trained as beekeepers – which will help families pay school tuition for their children.

These stories aren’t from NGOs or the lifestyle section of a local paper. It might be surprising, but they actually come from major corporations: Kellogg, which is working with growers and farmers to limit environmental impacts in its supply chain, and General Mills, which is helping farmers develop sustainable beekeeping businesses in Sierra Leone. Big changes are taking place in the agriculture industry, as some of the world’s largest brands increase their focus on having a positive social, economic and environmental impact, while continuing to grow and produce the food that millions have made a part of their daily lives.

This idea of “sustainable agriculture” is of increasing importance as today – more than ever before – consumers care about where their food comes from. According to a recent study by Trace One, 68 percent of U.S. consumers said they are not provided with enough information about what is in their food and where it comes from. In fact, the vast majority of consumers reported that it is important to know where their food is coming from. At the same time, target consumer groups like Millennials consider sustainability as an important factor in making purchasing decisions. A recent Cone Communications study found that while health and safety and nutritional value remain the most important, 77 percent of Millennials consider product sustainability as an important factor.

Given consumers’ motivations and evolving feelings about food, it makes sense companies like General Mills and Kellogg’s are telling compelling stories about where their products come from and how they’re made. So, what does it take to craft a powerful narrative and develop effective communications about corporate sustainable agriculture efforts? Let’s take a look at two other companies that are doing it well.

- Unilever has set ambitious goals, such as committing to zero-deforestation associated with key ingredients. This is notable, given deforestation is responsible for an estimated 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. The company has also partnered with WWF to educate consumers about the issue. Meanwhile, it is supporting smallholder farmers through education and training, underscoring Unilever’s commitment to enhancing livelihoods across its value chain – a key component of the company’s Sustainable Living Plan. And, CEO Paul Polman is a vocal leader in the corporate responsibility space. These are just some of the reasons why Unilever topped GlobeScan’s 2015 sustainability leaders list.

- Stonyfield is a New Hampshire-based organic dairy brand that provides a SourceMap for consumers interested in where their food comes from, allowing them to check out farm conditions and the history of individual yogurt ingredients, such as milk, peaches and pears. The company offers grants to empower the next generation of organic dairy farmers, which support the industry and local economies. Stonyfield also supported the development of farmer-owned processing plants for banana famers in Costa Rica, which can drive local economic growth and increase quality, efficiency and income for farmers.

As companies strive to make progress when it comes to sustainable agriculture, here are seven tips for building a communications strategy that is both effective and compelling:

- Define your core essence. What does the company stand for? What does it believe in? This will become the “red thread” that comes across clearly in all communications and storytelling, across all channels.

- Be authentic. What is the clear vision for how the brand can contribute to making the global agriculture industry more sustainable? Explain how the issues you are addressing are core to the company’s business and long-term success.

- Set ambitious goals for improvement. Whether it’s empowering 5 million women by 2020 (Coca-Cola) or eliminating deforestation for core commodities (Unilever), setting time-bound, science-based and measureable goals will lend credibility and resonate with stakeholders. Not to mention, it makes your work newsworthy.

- Demonstrate executive-level leadership. CEO or c-suite ownership and communications around your sustainable agriculture efforts helps to demonstrate the importance of corporate responsibility efforts for a brand.

- Engage with stakeholders and consumers. Seeking input from the experts on the ground and involving them in campaign planning is crucial from a programmatic perspective, but will also be a key component of authentic storytelling moving forward.

- Make communications both relevant and personal. Once you understand the needs of each stakeholder, make sure to communicate what’s most relevant to them, in a way that makes the issue both personal and urgent. And of course, creative, human and emotive storytelling across all channels is a must.

- Report on progress and communicate your challenges. Setting goals is just the start. What’s most important is reporting on the progress the company is making and being transparent about the challenges you face.

Aaron Pickering is an account director on Cone Communications’ Corporate Communications team with over a decade of experience in strategic public relations, project management and media relations. Aaron advises corporate and nonprofit clients on how to effectively communicate with diverse stakeholders, articulate their vision and build brand awareness. He has worked with companies and organizations across industries and on a range of issues – from labor and human rights to the environment – to tell compelling stories, cultivate media relationships and engage stakeholders to launch strategic public relations campaigns that change minds and drive results. Aaron also teaches as an adjunct professor at The George Washington University.

Did We Make a Difference? Calculating the Social ROI on Philanthropic Dollars

By Nicole Anderson, President of the AT&T Foundation

In an era of strained public investments in education, philanthropy has never been more important to ensure that all students have the opportunity to succeed in school, in the workforce and in life. Fortunately, a groundswell of foundations and corporate funders has risen to the challenge. In fact, education philanthropy is projected to top a record $2 billion in 2016 — a 7 percent increase over last year, according to a Grantmakers for Education report.

As more organizations roll up their sleeves to tackle some of the most stubborn problems in education today, they also face increasing pressure to demonstrate how the programs they run are impacting the issues they are working to solve. Board members, shareholders, funders and the public want to know just how their philanthropic dollars are driving positive social change.

These are important questions, to be sure, but there isn’t always a straightforward answer. Articulating the social return on investment (ROI) for programs that help our vulnerable students succeed is a complex undertaking; the outcomes we seek are often difficult to define in dollars or data points. Even so, as social investors, we still need tools and metrics to show us that our funds are being invested in the most effective programs and having a real positive impact on students in the present and future.

When we at the AT&T Foundation launched AT&T Aspire, our signature philanthropic program with a specific focus on improving the U.S. high school graduation rate, we knew we needed to measure how our investments led to positive impacts on student outcomes, but we were less clear on how to go about doing it. Who would collect the data? Would the organizations be able to meet our measurement expectations? And the question of impact — how we would show social change as a result of our giving — loomed large.

Needless to say, our first competitive request for proposal (RFP) program was a learning experience, both for us and the non-profits. But it made us smarter, and we had a clearer sense of what our expectations would be for future programs. We also learned that we can’t expect organizations to do it without support. In subsequent years, we continued to hone our processes for articulating goals and metrics, prioritizing outcomes and providing technical assistance and resources to build our awardees’ capacity to report their impact.

We are still learning and improving, but the data are beginning to show positive outcomes — for students and for society. Initial findings from the first year of our 2014 competitive two year funding program, conducted by the independent research firm Westat, show that students (grades 10-12) who participated in AT&T Aspire-supported programs are more likely to graduate than their peers. And for Aspire students, who in comparison to their matched peers, moved on track to graduate (or were preventing from falling off track), the overall increase in life-long earning and taxes for these students is estimated to fall between $89 and $283 million. In that data point, we see the life changing impact of our funding.

To put a finer point on it: Not only are we able to measure a student’s likelihood of success as a result of interventions, we’re now able to estimate the lifetime value — in personal income and taxes — of programs funded through AT&T Aspire. These results tell us our social investment strategy is working. When we bring underserved students across the finish line in high school and provide economic value to communities where students live, learn and work, everyone wins.

This data certainly help us make the case for effective philanthropy, but they also help us to see in which programs and types of interventions we should invest and what to look for in new investments. And indeed, there is more work to be done. While the U.S. high school graduation rate has improved to 82.3 percent, according to the 2016 Building a Grad Nation report — representing nearly 2 million people in the last decade alone — troubling graduation gaps persist for students of color, students with disabilities, English-language learners and low-income students. This is why we just awarded 18 organizations a total of $10 million to continue to lead the way towards meeting Grad Nation’s goal, which we share, to have a 90 percent high school graduation rate by 2020.

We know that a high school diploma is the first critical step to achieving long-term success for individuals. It also leads to greater economic gains for the country. Together we can continue to move the needle, but it requires further investments in programs that work and are able to demonstrate tangible returns. The data confirms investment is warranted. More students graduating confirms lives are transforming.

Image credit: Flickr/TaxCredits.net

Nicole Anderson is Assistant Vice President for Social Innovation at AT&T and President of the AT&T Foundation.

CDL partners to launch sustainability academy to achieve climate goals

by Antonio Pasolini—The city-state of Singapore is making a pioneering move towards meeting its climate mitigation goals. A joint effort by City Developments Limited (CDL) and the Sustainable Energy Association of Singapore (SEAS), the Singapore Sustainability Academy (SSA) is described as “the first major People, Public and Private (3P) ground-up initiative” to help the small country meet its goals laid out in the Sustainable Singapore Blueprint and the recently-released Climate Action Plan.

Expected to be completed in March 2017, the Academy’s goals is to promote a low-carbon economy, resource efficiency, and sustainable practices among businesses and the community, in particular, youths. One of the innovations of the initiative is that for the first time a local private property developer and a non-profit organisation have teamed up to create a major training and networking facility on sustainability.

Suitably, SSA will be located atop CDL’s City Square Mall, Singapore’s first eco-mall and will consolidate all of SEAS’ operations for Asia, besides serving as the platform for the organisation to implement its existing plans.

Singapore has sent out clear signals it is serious about climate change. Prior to the Paris Agreement, it had pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 36 percent compared to 2005 levels by 2030.

It is also working towards stabilising its emissions with the aim of peaking around 2030. How this ambitious plan going to be achieved is detailed in the Climate Action Plan released on July 10.

“There is tremendous potential for the private sector to play a major role in our journey towards mitigating and adapting to the devastating effects of climate change. The Singapore Sustainability Academy by CDL and SEAS is an excellent 3P ground-up initiative in the push forward to become a more sustainable Singapore,” Dr. Amy Khor, Senior Minister of State, Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, said during the launch event.

As part of its mission to involve business, government and the public, SSA will invite senior policy and decision-makers to share on relevant subjects and explore other key sustainability topics related to banking, power, building and infrastructure sectors.

The building

The academy will be spread across 4,300 square feet. It will comprise classrooms, a veranda, an office, and an exhibition gallery. The zero-energy building itself will be a source of inspiration, with 3,230 sq. ft. of photovoltaic panels and a monitoring system to track real-time energy generation and consumption.

Designed and built by REC in Singapore, the solar panels expected to generate an annual energy yield of over 60,000 kilowatt hours (kWh)m beating SSA’s estimated annual energy consumption of about 50,000 kWh.

There will also be an automation control and energy monitoring system that adjusts light and air-condition to demand in order to save energy and maintain comfort at the same time.

The initiative is also supported by the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, the National Environment Agency, the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Building and Construction Authority.

Image credit: CDL

Is the UK too reliant on EU workers?

International Tourism Partnership launches Hotel Water Measure Initiative to set industry standards

COP21: Getting down to business

by RP Siegel — COP21 has been hailed as a historic event because of the way it facilitated 196 countries to come together in support of a shared ambition to head off accelerating climate change before it’s too late. It’s a tremendously important moment, or at least it will be if those words and promises lead to action. It raises the unprecedented possibility of all the peoples of the world working together towards a common goal. A newly released report by Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) along with the We Mean Business coalition, entitled “The Paris Agreement: What is Means for Business,” lays out a set of recommended actions for businesses and investors in response to and in support of COP21.

The report translates the multiple outcomes of the Paris Summit into a concise set of straightforward statements:

• [What]: Climate ambition is universal (2°C with a stretch goal of 1.5)

• [When]: The international community has committed to net zero emissions in the second half of this century.

• [Where]: All countries are subject to the same reporting and verification framework

• [How]: Financial flows are committed to shift towards low-carbon and high-resilience investments

• [Who]: The private sector is recognized as an integral part of the solution

The days of businesses focusing exclusively on profits, while governments make sure that no one gets hurt, (minus exceptions made for special relationships)—are not yet over, but a new vision of a better way for the world, and for businesses in particular to work has been articulated and is gaining considerable traction.

An overarching outcome of the summit is the establishment of a level of policy certainty not seen before in this area. Certainty is as crucial for investment as sunlight is for the plants that feed us. For investment, there is a goal of US $100 billion (£76.8bn, €90.3bn) per year from the governments of developed countries by 2020. It is understood that substantial additional expenditure will be made. An estimated $90 trillion (£69.1tn, €81.3tn) will be spent on infrastructure by 2030, most of it in developing countries. So, as long as the commitment is to spend that money on sustainable infrastructure, there should be no problem achieving the required investment level. That, in turn, should provide ample incentive for both businesses and companies to invest further in sustainable technologies.

The main process is for each country to prepare national climate plans that will be updated every five years. We are in the preparatory phase for the first cycle which begins implementation in 2020. At that time, the new or updated national plans are submitted, and the process repeats every five years afterwards until the goal is reached.

Another major element coming out of the summit is Mandatory Reporting & Verification. This is a commitment on the part of participating countries to tell the truth when it comes to their emission levels, as least as well as they understand them. This effort will be greatly enhanced by the deployment of new technologies such as space-based verification systems. Not only will this allow countries to get a better handle, with considerable detail, on what their actual emissions are, it will also allow for independent, third-party verification.

Cross-border Carbon Pricing will provide a sizable market within which countries can match capabilities with needs, while at the same time providing continuous incentive for each country to follow a cleaner path to energy production and consumption.

Recommendations

Given this backdrop, the authors make the following recommendations to businesses hoping to thrive in this emerging environment. They are as follows:

1 ) Seize the Opportunity – We are on the brink of a tremendous surge in demand for clean energy solution of various kinds. China alone invested $110 billion (£84.5bn, €81.3bn) in clean energy last year, an increase of 17% over the previous year. Other major economies will likely follow a similar path in their effort to meet this stated goal. This is now relatively predictable. Embedded in these commitments is a 4,400 TWh of renewable supply that will be required by 2030. That will bring the renewable portion of global electricity generation up to 32%. Renewable capacity in OECD countries should surpass 54% by 2040. The dollars required to get there are considerable. IEA estimates annual expenditures close to $230 billion (£176.8bn, €208bn) in the 2026-2040 time frame.

2 ) Put a price on carbon – Based on data provided by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, onshore wind is already cheaper than both coal and natural gas in the EU. It is expected to hit that point in both the US and China no later than 2023. Utility scale solar will come down to that level a few years after that, all without new government interventions. That’s good but it may not be good enough. Those cost transition points can be accelerated immediately by putting a price on carbon, which will also allow it to more accurately reflect its true cost to society.

3 ) Manage climate risk - According to the World Economic Forum’s 2016 Global Risk Assessment Report, failure to mitigate or adapt to climate change is the highest impact risk to business for years to come. A recent BSR survey showed that 75% of suppliers felt that climate change would impact their business, yet only 50% had taken action to prepare for this. Risks to be considered include: physical and operational risk, input risk, market risk, financial risk, reputational risk, and regulatory risk. Several detailed examples from across the globe are provided including textiles, manufacturing, agricultural and insurance.

4) Be bold and be recognized - Businesses that have moved aggressively “have benefited from an average 27% internal rate of return on their low carbon investments, alignment with incoming climate and energy regulation, first-mover advantages in low carbon markets, more resilient operations and supply chains, and a stronger reputation among employees, consumers, and other stakeholders.”

Image credit: Moyan Brenn Flickr Creative Commons

3p Weekend: These Partnerships Are Out to Revolutionize Transportation

With a busy week behind you and the weekend within reach, there’s no shame in taking things a bit easy on Friday afternoon. With this in mind, every Friday TriplePundit will give you a fun, easy read on a topic you care about. So, take a break from those endless email threads and spend five minutes catching up on the latest trends in sustainability and business.

In this day and age, everything is changing. Each day brings with it a new smartphone, wearable device or tech-driven service that promises to make our lives simpler and easier. These "disruptive" innovations span every industry, from energy generation to agriculture.

But perhaps no industry is evolving more quickly than transportation -- and it probably needs to be that way: This year, transportation outpaced the utility sector as America's largest carbon emitter.

This shift brings with it an unavoidable need to cut those emissions down to size, particularly as the U.S. and China aim to formally join the Paris agreement before the G20 Summit this weekend. The emissions cuts the agreement requires demand big change. And no single company can go it alone.

Fortunately, this reality hasn't escaped big players in the space. This week we round up seven partnerships that aim to revolutionize transportation. Do you think they can?

Ford taps partners for driverless cars

Ford CEO Mark Fields made a big announcement last month: "Ford will be mass-producing vehicles with full autonomy, within five years."

Ford is hardly the first company to eye driverless cars in earnest. But Fields' announcement of a mass-produced model goes the furthest so far. And while rumors circulated that the automaker would link up with Google to develop autonomous cars, the partnership has yet to materialize.

That said, Ford won't go it alone when it comes to the next generation of personal transport. Four new partnerships -- with Velodyne, SAIPS, Nirenberg Neuroscience and Civil Maps -- will help the automaker hone functions like distance sensing and machine learning.

And while the Google partnership seems to be on the back burner, we wouldn't count it out just yet. This spring, the two companies joined a cohort of stakeholders advocating for federal approval of driverless cars. And Ford may need more partners if it hopes to make a mass-produced vehicle a reality by 2021.

GM bets big on Lyft...

As the two largest ride-sharing services, Uber and Lyft, battle it out for domination in the future of transit, automakers previously tied to personal mobility are wary of being left behind.

With the financial crisis and auto bailout still top of mind, many are surprised General Motors even made it this far, but the automaker has no plans to throw in the towel. And with a new partner in Lyft, GM could be ready to turn over a new leaf.

At the start of this year, GM announced it would invest $500 million in the ride-sharing company to envision the future of auto transport. GM will provide cars at “hubs” for Lyft drivers who want to make some spare cash, but don’t necessarily own a car. The companies also say collaboration on autonomous-driving technology will be a component of the partnership.

... and Toyota strikes back with Uber

A few months after GM linked up with Lyft, Japanese automaker Toyota announced a "strategic partnership" of its own -- with Lyft's larger rival, Uber. Toyota said it planned to offer cars to Uber drivers through "flexible" leasing plans. The automaker didn't disclose how much it invested in Uber. But a source close to the situation told the Wall Street Journal that the figure was under $100 million, far lower than GM's investment in Lyft.

But the Japanese auto label is making moves, and those dollars and cents may not matter. The creator of America's most popular hybrid, the Prius, is now out to revive the oft-discounted hydrogen economy. Toyota's hydrogen-fueled Mirai made its debut this year, turning heads in the clean-tech space. (3p's Bill Roth tested the Mirai side-by-side with the Tesla Model S. Click here to check it out.)

And Uber is making moves of its own, although not the ones labor advocates may like. Despite its car-leasing partnership with Toyota, Uber is rapidly expanding its own leasing service, Xchange Leasing, which critics say is often predatory.

Walmart tests delivery services with ride-sharing giants

Gone are the days of hauling rickety carts up to that fifth-floor walk-up. If you live in a major American city, chances are you have at least a few options for getting your groceries delivered. Startups like FreshDirect made a splash in the space. And larger competitors, like Amazon and its Amazon Fresh service, are now looking to jump on the bandwagon.

You can now add Walmart to the list -- and the big-box retailer hopes a secret weapon can help it take the lead. At its annual shareholders meeting this summer, Walmart announced it would explore a partnership with Uber and Lyft to expand its grocery-delivery service.

In a few test locations, Walmart customers will submit their online orders, personalized shoppers will gather the items, and then an Uber or Lyft driver will haul the order the “last mile” to the delivery destination. As is often the case with Walmart -- and Uber and Lyft, for that matter -- some questioned how well the partnership will work out for employees. We'll keep an eye on this one as it develops.

Zipcar and Yakima deliver outdoor adventure to urbanites

Zipcar is the world’s leading car-sharing network. Yakima Products makes vehicle racks and cargo solutions. It seems like a match made in heaven. And in August, they proved it is.

Thanks to a new partnership, the two companies will bring Yakima bike, ski and surfboard carriers to Zipcars in North America. This exclusive deal enables Zipcar members to enjoy their favorite outdoor activities outside of the city without the cost and hassle of owning a car (or perilously bungee-cording bicycles into the trunk of a rented sedan).

According to the Outdoor Industry Association, 34 percent of the outdoor consumer market lives in cities. The partnership enables urban adventurers to "live a car-free or car-light lifestyle without sacrificing their ability to get out of the city and enjoy their favorite outdoor activities," the two companies said in a press release. More than 150 Zipcars in 17 North American markets will receive the new treatment.

Tesla and Panasonic build battery 'Gigafactory'

https://player.vimeo.com/video/108958187Back in 2014, the partnership between Panasonic and Tesla was the handshake heard round the world. The time-honored tech firm and electric-vehicle upstart agreed to work together on a battery 'Gigafactory.' The completed factory, they promised, would support the manufacture of 500,000 electric cars per year, and also produce utility-scale batteries fit for municipal energy storage.

No sooner had the partners announced their plans than states began lining up to host the new factory. In the end, it was Nevada that came out victorious. But that was over two years ago. How are things progressing?

Well, it depends on who you ask. Tesla CEO Elon Musk told a group of journalists this summer that EV batteries will start coming off the assembly line next year. That's a pretty optimistic statement considering that the factory was less than 15 percent completed as of late July. But 1,000 people are working seven days a week to hit the deadline, reported Jack Stewart of Wired.

After acquiring SolarCity this summer, the automaker plans to seek a new round of financing to support the Gigafactory, as well as meet demand for the forthcoming Model 3, Fred Lambert of Electrek reported this week.

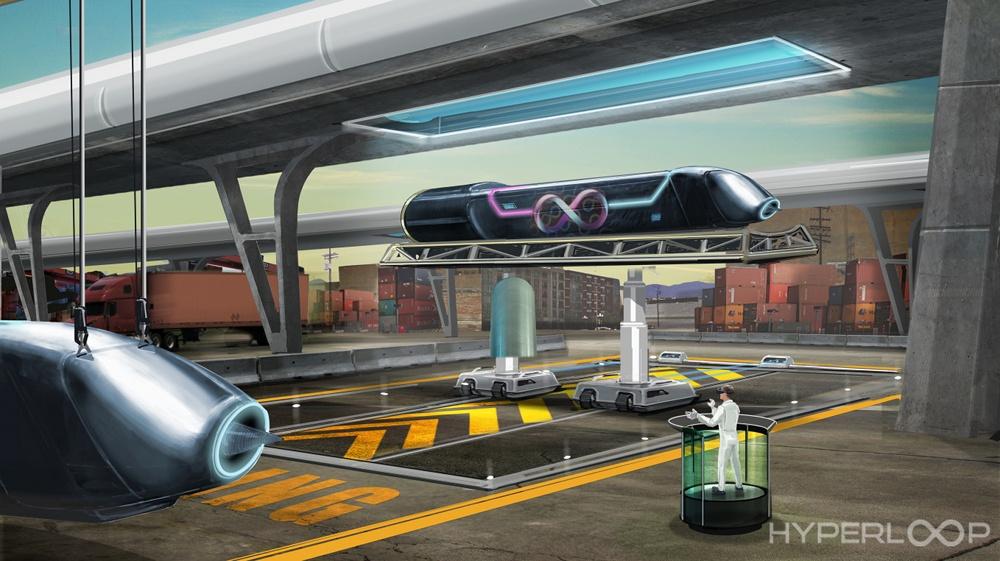

Players converge on the Hyperloop

Clean-tech visionary Elon Musk first unveiled his idea for a high-speed ground transport system called Hyperloop back in 2013. The concept — in which passengers are transported in magnet-propelled capsules at more than 750 miles per hour — was quickly dismissed by many as a pipe-dream.

Musk opted not to pursue the concept himself (in all fairness, he has a lot going on). But he open-sourced his plans, allowing partners to convene and make his vision a reality. Earlier this year, three similarly-named companies -- Hyperloop Technologies, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies and Hyperloop One -- claimed to be inching closer.

Hyperloop One was the first to complete a public test. But all three companies, along with a few others, are still in the race. In the most recent development, Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (HTT) scored a coveted partnership with German railway company Deutsche Bahn. The two firms plan to collaborate on a new “Innovation Train” that will combine Hyperloop technology with more traditional transportation methods, Jacob Kleinman of Techno Buffalo reported in July.

Will it be enough to bring HTT's technology to the head of the pack? Only time will tell. But we hope to see more collaboration, along with a healthy dose of competition, to move this groundbreaking concept forward.

Image credits: 1) and 6) Courtesy of Zipcar and Yakima; 2) Ford; 3) General Motors; 4) Toyota; 5) Walmart; 7) Hyperloop Technologies, Inc. (all editorial use only)

Video courtesy of Tesla