New ideas for a new economy

SEC Investigates ExxonMobil As Climate Science Witch Hunt Continues in Congress

In an ongoing climate science witch hunt, U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith issued controversial subpoenas to state attorneys general and NGOs investigating ExxonMobil. Hearings began this week in the House Science Committee, of which Smith is the chair. Smith says the investigation infringes on ExxonMobil's First Amendment rights. But the attorneys general, as well as groups like Greenpeace and 350.org, say Smith violated their free speech rights by attempting to derail the investigation through excessive subpoenas.

Tom Wakely, the Democratic candidate who is challenging Smith for his congressional seat in the November election, agrees. "To abuse political power for the purpose of advancing corporate interests -- and to do so under the guise of academic integrity and freedom of speech -- is the epitome of corruption. Lamar Smith is completely overstepping his bounds as the chairman of the House Science Committee."

But other branches of the federal government refused to roll over for ExxonMobil, which is also one of Smith’s largest benefactors. According to several press accounts, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched an investigation into the oil and gas giant on two fronts: the company's accounting procedures and its valuation of assets.

The SEC says ExxonMobil failed to lower the estimated value of its oil and gas reserves after the prices of these commodities fell, and it plans to evaluate further, the Wall Street Journal reported on Wednesday. And the problem appears to be exclusive to Exxon among the big-four oil giants. Shortly after global oil prices tumbled downward, BP lowered its assets’ valuation by $3.6 billion in order to reflect a more accurate estimate of its reserves. ExxonMobil’s largest competitors, Shell and Chevron, also reduced the dollar value of their assets, as most energy industry analysts estimate oil prices will stay low for another two year at minimum.

The SEC investigation will also focus on how ExxonMobil is, or is not, accounting for the long-term risks climate change poses to its financial performance. In a world where both developed and developing countries are investing in renewables in order to expand energy access and mitigate potential climate change risk – even during a time when fossil fuel prices are low and many subsidies for renewables have been either reduced or eliminated – the fact that more of those reserves may stay in the ground, and therefore never sold, could have a longstanding impact on ExxonMobil’s valuation and stock price.

The bottom line is that it is illegal for a company to misrepresent asset values and other financial information to investors.

In an emailed statement to TriplePundit, Annie Leonard, executive director of Greenpeace, said:

“This investigation is a welcome opportunity for transparency from the fossil fuel industry. We know Exxon has published projections showing that demand for oil and natural gas will continue growing for decades to come -- projections which are flatly incompatible with limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, as called for by the Paris climate accords. What we don’t know is how Exxon’s balance sheet would change if the world meets the climate challenge.”The SEC requires companies to disclose risks related to climate change, and has for several years. Critics of the agency, however, say the huge step to mandate climate disclosures was followed by years of tiptoeing around the issue. Earlier this year, three former U.S. Treasury Secretaries, Republicans George Schultz and Henry Paulson and Democrat Richard Rubin, urged the SEC to take greater action on how it monitors financial disclosures tied to climate change.

Congress, however, balked at any constructive discussion of the issue, leading the House to pass a spending bill that included an amendment prohibiting the SEC from enforcing its climate risk disclosure rules. But advocates of more stringent accounting practices say that such legal maneuvering is foolhardy. They point to the example of coal producer Peabody Energy, a stock that earlier this decade was valued at over $700 a share. Natural gas largely led to the company’s decline, but more institutional investors and individual buyers of securities have also turned away from coal over climate change concerns.

Yet Peabody was accused of knowing that coal prices would collapse, and communicating internally. Instead of telling its shareholders, company execs said they believed the discussion over climate change would not affect Peabody's business. The company declared bankruptcy earlier this year, and its stock currently trades at about $1.50 in over-the-counter trading. Hence the argument that, had the company been more forthcoming with its shareholders, fewer people would have lost their money (or as much money if they could have shed the stock sooner with better information).

So, investors are the big winner of the SEC decision to follow through on what the agency is supposed to do. The big loser is Smith, chair of the House Science Committee. For almost a year, he used his position to take a stand on what he says is an attack on ExxonMobil’s First Amendment rights.

The SEC reportedly based its investigations on the work of New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, who is part of an investigation on whether ExxonMobil’s climate science research is linked to any fraudulent activity by the company. Smith in turn used the power of subpoenas to demand information about these investigations from Schneiderman, other state attorneys general and NGOs. These organizations in turn pushed back against what they call Smith’s abuse of power, which led to the congressional hearings last week.

"Lamar Smith's vendetta against the state attorneys general and climate science groups investigating ExxonMobil is evidence in itself that the corporation has something to hide," Wakely told 3p. "It's no coincidence that Smith is so preoccupied with keeping Exxon's research on climate change under wraps given the fact that he's received nearly $700,000 in funding from the oil and gas industry."

Smith and his allies are lone warriors in what is both a social and market shift toward new forms of energy. “Millions of people around the globe have long demanded action to hold Exxon accountable. This investigation marks a moment of reckoning for the corporation,” Katherine Sawyer of Corporate Accountability International told TriplePundit in an email. “Coupled with attorneys general investigations into Exxon’s campaign of climate denial, the SEC’s probe means the corporation’s days of deception are numbered.”

Image credit: SEC/Flickr

Amazon's Jeff Bezos Doubles Down on Wind Energy

The U.S. Energy Department released a new report predicting a huge drop in the cost of wind energy by 2030, but Amazon is not waiting around for that to happen. The company is already heavily invested in wind energy and just signed on to buy 90 percent of the output from a new 235-megawatt wind farm in Scurry County, Texas.

The news comes with an interesting political twist. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is a huge fan of renewable energy. He also recently purchased the Washington Post, and was largely credited with galvanizing the languishing publication into reporting aggressively on the 2016 presidential election cycle.

That approach prompted GOP presidential hopeful Donald Trump to attack Jeff Bezos and his ownership of the Post during the heat of the primary season. To complete the circle of twists, Donald Trump is no fan of renewable energy in general, and wind energy in particular.

Amazon hearts wind energy

Amazon's wind energy ventures first crossed the TriplePundit radar last year, when the company announced an agreement with Ibderdrola Renewables for a 208-megawatt wind farm in North Carolina.

Amazon also has an interest in wind farms in three other states: Indiana, Ohio and Virginia.

The new Texas wind farm, dubbed Amazon Wind Farm Texas, will be the company's largest renewable energy project so far. The developer, Lincoln Clean Energy, is an up-and-comer in the wind industry. According to our friends at Fuel Fix, Lincoln already has two Texas wind farms to its credit and it is moving ahead with two more projects in the 200-megawatt range. It also has fingers crossed for a third Texas project that tops 200 megawatts.

Amazon's Texas wind farm is due to come online toward the end of next year, with more than 100 turbines generating about 1 million megawatt-hours annually. According to Amazon, that's enough to power about 90,000 typical U.S. homes.

The project is particularly interesting because it involves large wind turbines that have a rotor diameter Amazon compares to the wingspan of a Boeing 747. The new Energy Department report indicates that a continued drop in wind energy costs will be largely due to just that factor -- namely, larger wind turbines.

All together, Amazon's wind projects in Texas, North Carolina, Indiana, Ohio and Virginia will generate more than 2.6 million megawatt-hours annually. The idea is to counterbalance the existing and predicted demands on the grid that Amazon anticipates from its cloud-based Amazon Web Services data centers.

Amazon committed to 100 percent renewable energy for its infrastructure globally, and the new project will get the company closer to that goal. Amazon was up to 25 percent as of April 2015, and it expects to close in on 40 percent by the end of this year.

As for why Amazon is such a big fan of wind and solar, the looming global warming crisis is only part of the equation. Aside from that, the importance of engaging with more stable, reliable energy sources has come into sharp focus this week, on the heels of yet another major pipeline spill that is bringing high prices, long lines and empty pumps to gas stations all over the southeastern U.S.

Texas hearts wind energy

If Texas and wind energy don't sound like they go together, you might have some catching up to do. Texas has iconic status in the history of U.S. oil and gas development, but it didn't stop there. After propelling the nation into the fossil fuel landscape of the 20th century, Texas has become a main driver of the transition to renewable energy.

That's particularly true of the state's wind industry, but wind farm development is only part of the equation. The other, equally important factor is the construction of the billion-dollar CREZ wind energy transmission line, to bring the juice from those far-flung wind farms into urban centers.

For his part, Bezos doesn't seem ready to slow down any time soon. Last time we checked, he was looking forward to relocating energy-sucking, heavy industrial activities into space, where they could be powered 24/7 by the sun.

In recognition of Emmy night, let's also give a shout-out to Jeff Bezos for Amazon Studio's "Transparent," which just won a bunch of trophies.

Photo courtesy of Lincoln Clean Energy

Taking Care of Business in the High-Road Economy

By Zach Bernstein

It’s been an article of faith that any measure that would be good for workers -- raising the minimum wage, guaranteeing paid leave, boosting worker ownership -- must be bad for business and the economy.

Of course, that’s not actually the case. Results-minded companies are embracing the idea of workers as resources worth investing in, not just as commodities. They’re adopting what groups like the American Sustainable Business Council (ASBC) call “high-road” business practices. The high road covers a lot of ground, and it’s only starting to gain prominence with policymakers and the media. In time, however, it could change for the better how companies take care of business.

High road, higher profits

Some high-road policies are fairly well known -- raising the minimum wage, guaranteeing paid family leave, paid sick days, and more. If you’ve been following the news, you’ve probably seen a story on how important these policies are to workers, or on how far we’ve fallen behind other nations in guaranteeing them, or how a state or city has passed laws guaranteeing one or more of these benefits.

Other high-road policies are less familiar -- increasing worker ownership to give more employees a share of their company’s success; “banning the box” to give applicants who’ve served time a fair chance at a job; supporting worker skills development through funding for college or other training programs.

These widely different policies, aimed at different groups, have one thing in common: They benefit not just the worker, but also the bottom line.

Pay now... or pay later

High-road policies, put into practice, help the bottom line because they unleash the ingenuity, energy and devotion employees at all levels have to offer – and want to offer – if their basic human needs are considered and their efforts are appreciated. High-road policies earn a level of loyalty and productivity no amount of labor-intensive micromanaging can instill.

When a company invests in its people’s wellbeing, those people become invested in the company’s success. Companies can set rigorous standards and ambitious goals because people aren’t trying to just get by, or working with one eye on the clock and the other on the door. They’re motivated to stay, which means employee turnover is lower. Companies that reduce the high cost of turnover, both in lost productivity and having to recruit and train replacements, come out ahead. While measurements vary, one estimate found that the cost to replace a mid-range position worker could be 20 percent of his or her salary, and cost to replace an executive could be as high as 213 percent.

That’s without knowing for sure you’ll get your money’s worth from that new hire. While it’s harder to peg a specific ROI for engaged, productive employees, high-road policies help ensure people come to work focused and motivated. Whatever your job level, if you’re worried about a new baby or seriously ill family member, if you’ve got the flu yourself, or if your pay is so low you’re juggling rent and other necessities, it’s hard to stay focused, work hard and fast, or make a good impression on those valuable customers.

Investing in high-road benefits does have a cost to the company, of course. A higher wage means less cash on hand; paid leave also means shifting schedules around. But like any good business investment, these benefits can be expected to pay off down the road – perhaps sooner, if you let employees know what you are doing, and why.

Practice makes perfect

Just ask Lauren Rasnake, head of development and culture at online retailer UncommonGoods, which sets a minimum wage of $14 an hour -- including for seasonal workers brought in to cope with higher demand during the holidays. “There’s obviously a significant cost to paying $14 an hour for a warehouse operation that grows by 500 team members during [the fourth quarter],” Rasnake said, “but we make adjustments across the business because this is the company’s value.”

Fair pay incentivizes those seasonal workers to work hard so they’ll be asked back, and they also come back year after year, which saves the company time and money on recruitment. “Being an employer that people continually want to come back to, in a seasonal capacity, is really exciting,” Rasnake says.

Or ask John Abrams, president and CEO of South Mountain Co., an architectural firm on Martha’s Vineyard that focuses heavily on environmentally friendly buildings. The company is a worker cooperative that offers employees shares after five years and 7500 hours of work. “I believe that whatever modest successes we have had are directly attributable to the decision to become a worker cooperative 30 years ago,” Abrams said.

Initially, there were concerns about how becoming a cooperative might change the company’s values, but South Mountain solved this by factoring ownership interest into its hiring criteria. The company assumes all new hires will take an ownership stake, and works to ensure their values mesh with the company’s. So far, it’s gone well.

“Anyone who says that providing extensive benefits is bad for business can’t possibly have run a successful business, at least not in the way I define success,” Abrams concluded. “I walk in each morning and say to myself, ‘Wait a minute; I get to work with all these people, all day long, and get paid for it?’ That’s the kind of place I want to work, and that doesn’t happen by accident.”

As more companies make the business case for high-road practices, more policymakers will listen -- as they often do when the topic is more jobs and more growth in their regions. But getting all firms to take the high road will require many more Innovative executives to lead the way by going public with their support. One way is to sign these High Road Workplace Principles.

Taking care of business should mean taking care of employees – every employee in every business. With enough business support, some day it will.

Image credit: Flickr/HD_Vision

Zach Bernstein is Manager of Research and Social Media for the American Sustainable Business Council.

Patagonia's Founder Rewrites His Philosophy for a New Era of Environmental Crisis

Editor's Note: The following is an excerpt from the new edition of "Let My People Go Surfing" by Yvon Chouinard, including ten more years of business unusual.

By Yvon Chouinard, Founder of Patagonia

We believe quality is no longer a luxury. It is sought out by the consumer, and it is expected.

The Strategic Planning Institute collects data on the performance of thousands of companies. Its yearly report, titled PIMS (Profit Impact of Market Strategy), now shows quite clearly that quality, not price, has the highest correlation with business success.

In fact, the institute found that companies with high product- and service-quality reputations have average return-on-investment rates 12 times higher than their lower-quality and lower-priced competitors.

Whenever we at Patagonia are faced with a serious business decision, the answer almost always is to increase quality. When we make a decision because it’s the right thing to do for the planet, it ends up also being good for the business.

During the worst days of the Great Recession, I spoke on a panel of surf industry leaders about Patagonia's use of only organic cotton and efforts to clean up our supply chain. A CEO of one of the largest surf companies said he made a few T-shirts and hats from organic cotton, but had to stop when the recession hit. I asked how his sales were doing, and he mentioned they were down 20 percent. Ours were up 30 percent that year.

That company and others in the surf industry are barely hanging on now because they didn’t understand that their young customers have changed.

Product returns and bad quality in manufacturing cost millions of dollars annually. (In 1988, each return cost us an average of $26 to process, and that number has only increased.) But what is the cost of a dissatisfied customer? Surveys show few customers will contact a company about a problem, but up to half who experience problems will never purchase from that company again.

Patagonia is privately owned. We have no desire to sell the company or to sell stock to outside investors, and we don’t want to be financially leveraged. In addition, we have no desire to expand Patagonia beyond the specialty outdoor market. So, how does finance react to these very clear-cut dictates?

First of all, by growing only at a “natural rate.” When our customers tell us they are frustrated by not being able to buy our products because of constant out-of-stock situations, then we need to make more, and that leads to “natural growth.” We do not create artificial demand for our goods by advertising in Vanity Fair or GQ or on buses in inner cities, hoping to get kids to buy their black down jackets from us instead of the North Face or Timberland. We want customers who need our clothing, not just desire it.

We never wanted to be a big company. We want to be the best company, and it’s easier to try to be the best small company than the best big company. We have to practice self-control. Growth in one part of the company may have to be sacrificed to allow growth in another. It’s also important that we have a clear idea of what the limits are to this “experiment” and live within those limits, knowing that the sooner we expand outside them, the sooner the type of company we want will die.

Because of our pessimism about the future of a world economy based on limited resources and on endlessly consuming and discarding goods we often don’t need, not only don’t we want to be financially leveraged, but our goal is to have no debt, which we have achieved.

A company with little debt or with cash in the kitty can take advantage of opportunities as they come up or invest in a startup without having to go further in debt or find outside investors.

In an age when change happens so quickly, any strategic plan must be updated at least every year. Many Japanese companies don’t do yearly budgets; they do a new budget every six months. In our case, an inflexible plan would be centralized planning at its worst. It builds in a certain rigidity, a certain bureaucracy, that is oblivious of changing realities. A budget can be a valuable guideline and planning tool, or it can be a bludgeon.

We have to look ahead in other ways as well. It’s the role of financial people not only to tell you what happened, but also to prevent rude surprises in the future. A company should always be playing “what if” scenarios—e.g., what if all our top management goes down in an airplane crash, our warehouse burns down, our main computer melts down or gets a virus? We don’t need operational plans already set up to deal with these crises, but we do need to identify which could strike so we are less likely to take a hit.

That same desire for transparency extends to our dealings with the government. We don’t play games with the tax man or auditor. Our tax strategy is to pay our fair share but not a penny more. We don’t, with clever advice, develop complex schemes to avoid our taxes. The same holds true for our accounting procedures. We know of legal ways to change how we account for our money that would result in dramatically different reported earnings from year to year. In fact, we could, within accepted and legal accounting practices, like so many public companies, show a profit every quarter. But our accounting strategy is to use only those techniques that, in the view of our CFO, provide the most accurate and consistent reflection of our true financial position.

We are approached by prospective buyers almost weekly, and their intent is always the same. They see an undervalued company that they can rapidly grow and take public. Being a publicly-held corporation or even a partnership would put shackles on how we operate, restrict what we do with our profits, and put us on a growth/suicide track. Our intent is to remain a closely-held private company, so we can continue to focus on our bottom line: doing good.

Yvon Chouinard is the founder of Patagonia.

This is an excerpt from "Let My People Go Surfing" by Yvon Chouinard, published on Sept. 6, Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright by Yvon Choinard, 2005, 2016.

Arrest Warrant For Democracy Now! Host Sparks Questions About Press Rights

Last week, a North Dakota county issued an arrest warrant for a journalist who reported on the bloody standoff between protesters and Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) security guards days before. Democracy Now! host Amy Goodman followed protesters onto a construction site over the Labor Day weekend in order to cover the developing story. Her report and photos of security dogs being directed to harass and bite protesters went viral that night. Days later, Morton County issued a warrant for her arrest for criminal trespass.

While media outlets around the world denounced the call for her arrest, Goodman is only one of several journalists to find themselves on the wrong side of the law for doing their job. Goodman herself was quick to accuse the county of violating her rights.

"This is an unacceptable violation of freedom of the press," Goodman said in a Democracy Now! statement. "I was doing my job by covering pipeline guards unleashing dogs and pepper spray on Native American protesters.”

But as reporters continue to discover, in the eyes of local law enforcement, the journalist's right to tell a story may be protected under the First Amendment, but their right to uncover the story isn't.

And the issue seems to be more than whether the reporter "trespassed" in an effort to report the story. In 2014, at least six journalists were taken into custody during clashes between protesters and police in Ferguson, Missouri. One was Getty photographer Scott Olson, who routinely supplies photos to media outlets around the world. At least three reporters said they were detained for a "few hours" during the height of the protests and then released once they subsided. According to journalists covering the Ferguson demonstrations, those who weren't arrested were expected to research and report their stories from a cordoned-off area far from the actual police lines.

This summer, journalists covering a Black Lives Matter protest in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, after 37-year-old Alton Sterling was shot by police, found themselves in a similar predicament. Five journalists were arrested during the protest and charged with "obstruction of a highway" while doing their job, according to a statement released by Reporters without Borders. Those charged included the assistant news director for the local station WAFB, who allegedly stepped momentarily onto the highway to get a better shot of the protest.

The right of access is a prickly issue for news journalists who often assume their right to dig for a story is inherent in their right to report what they found. After all, they argue, how else are they going to accurately substantiate and report stories to the public? How will they be able to interview observers and accurately time-stamp the events they report? For environmental organizations and interest groups concerned with water and environmental conservation, it's a valid question that goes far beyond whether a reporter can meet a press deadline or make a living. As Goodman's report on the DAPL protest demonstrates, the world seems to listen more closely and become more engaged in critical issues when people have a front-row-seat to a debate.

And to that end, journalists aren't the only ones finding roadblocks thrown in their way. Last spring, the North Carolina Public Utilities Commission informed the environmental organization NCWARN that if it wanted to appeal a $1.1 billion infrastructure project being built by Duke Energy, it would be required to post a $10 million bond.

The decision came after Duke Energy argued that any delays to its project could cost the company upwards of $140 million. After the nonprofit said it would be unable to meet the monetary demand, the Commission issued a permit to Duke Energy. The company then asked the Commission to increase the bond to $240 million for any further appeals, arguing that any interruption to its fast-tracked construction would cost even more to the energy company. Needless to say, the bond -- much like the controversy surrounding journalist arrests -- has a chilling effect on public scrutiny and environmental advocacy.

The impact such bonds can have on environmental advocacy was also summed up by Richard M. Clerkin, executive director of the the Institute for Nonprofits at North Carolina University: "Regardless of where we as individual residents of North Carolina stand on the environmental and business interests at stake in this matter, we ought to be collectively concerned about nonprofits needing to 'pay to play' when they raise their voices about public policies."

The Committee to Protect Journalists has the same kind of message when it comes to the arrest or unexplained detention of journalists trying to gather information at protests and in other controversial settings. It issued a list of eight steps that journalists would be advised to take "to avoid getting in harm's way or risking arrest" when reporting in settings of potential conflict -- which, they say, also include U.S. presidential conventions.

Of course, many reporters already put many of those points into practice, including by Amy Goodman, whose arrest warrant wasn't announced almost a week after her broadcast. With both sides of the DAPL conflict equally intent to exercise their assumed rights, journalists may find it increasingly difficult to do a job that starts with the right to information -- and the assumption that they won't be incarcerated for accessing it.

Image: Flickr/Chris Eaves

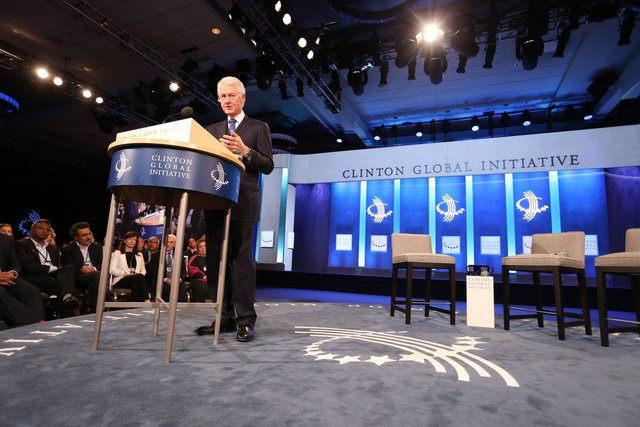

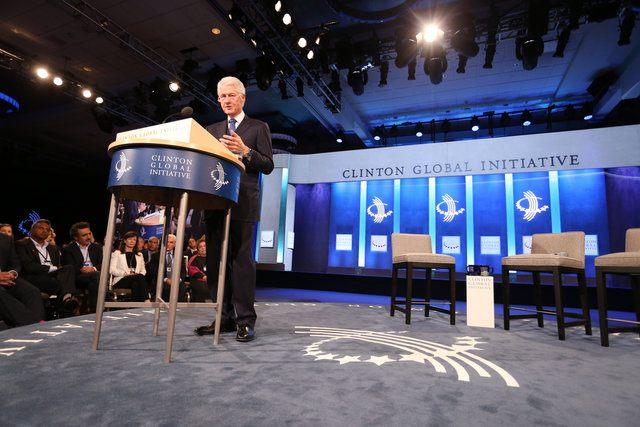

How the Clinton Global Initiative Changed the World By Changing Corporate Philanthropy

By Derek Yach

This week, the Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) convened top leaders from business, government and civil society for the 12th and final time. The end of the CGI Annual Meeting brings to a close not just an event, but a force that has helped change the way that companies everywhere think about social responsibility.

It’s been a decade since the Rockefeller Foundation (RF) endorsed me to advance CGI's global health work, which at the time was new and already starting to make waves in philanthropy. President Bill Clinton’s enthusiasm for encouraging the private sector to step up as key players in the social impact space — rather than leaving such work to governments and nonprofits — was met with both curiosity and skepticism at the time. But the leadership at Rockefeller recognized that CGI’s approach to addressing global challenges represented a fresh and needed way forward.

By facilitating the development of specific and measurable corporate plans to make a positive social and environmental impact — coined as Commitments to Action — CGI bet on the idea that corporate philanthropy could become more effective by embedding societal values into companies’ core business plans.

It turns out former President Clinton’s experiment worked. Taking philanthropy beyond the traditions of corporate social responsibility -- “doing well by doing good” -- is now the accepted norm for business 10 years later.

Its success paved the way for similar approaches, such as Michael Porter and Mark Kramer’s shared value, PepciCo CEO Indra Nooyi's “performance with purpose,” or Novo Nordisk's approach to the triple bottom line. All of these new approaches seek to find a new and explicit nexus between financial performance and social impact. As an advisor to CGI, I witnessed the powerful way former President Clinton’s platform stimulated, guided, cajoled and excited companies to go beyond their quarterly earnings reports and bring about positive social change through their commitments to action.

The direct benefits to society have been most obvious in the myriad global health commitments that have been carried out since 2005. Because of the collective body of commitments made by the CGI community, more than 114 million people have increased access to maternal and child health and survival programs, and more than 33 million people have increased access to safe drinking water and sanitation. Because of these commitments, more than 36 million people received treatment for neglected tropical disease, and more than $318 million in research and development funds was spent on new vaccines, medicines and diagnostics.

Due to the CGI community’s embrace of “doing well by doing good,” many companies transformed their business models to place health gains as central to their work. Traditional corporate philanthropy was soon reframed to meet market failures, including research, human capacity and humanitarian crises.

In fact, many of the United Nations Global Compact’s (UNGC) member companies are also CGI members. From the start, the CGI Annual Meeting was held during the week of the United Nations General Assembly, in the hopes of spurring synergy between goals and visions discussed on the East and West sides of New York City. CGI companies brought their experiences into the U.N. system at a time of unprecedented support for new forms of private-public partnerships to complement the role of government in addressing the newly adopted Sustainable Development Goals. This could allow for CGI’s commitments to reach the scale needed to have true global impact. Health should be a major beneficiary.

To accelerate progress on health, the UNGC is collaborating with Discovery Vitality and Novo Nordisk to elevate health within business in other areas that have become the norm, including the environment, labor, human rights, and corruption. Discovery Vitality's CEO, Adrian Gore, pledged to work with others to advance the integration of health metrics into corporate reporting in his plenary address at CGI 2013 in the presence of the Director General of the World Health Organization, Margaret Chan, and the session chair, Chelsea Clinton. This pledge is being advanced during the UNGC in 2016.

It has been a privilege to see how seemingly intractable health and social problems are being tackled in new ways that build on the joint expertise of companies, NGOs, academia and government. While at PepsiCo, our CGI commitments tackled undernutrition in Ethiopia and obesity in China, India, and Mexico. We’ve also partnered with the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, the American Beverage Association, and private-sector peers to curb the marketing and sales of unhealthy foods and beverages in the United States. All of these commitments had profound implications for the future of business models of food companies.

At Discovery Vitality, we are now expanding our CGI Commitments to Action with a very sharp focus. Vitality Shared Value Insurance is leading our members around the world to live longer lives while also transforming one of the oldest business models – life insurance. Our plan is having impact on health in profitable ways. CGI’s leadership in supporting and steering companies to do this will have enduring impacts on peoples’ lives and on the survival of our planet.

Few global platforms can claim to have the direct and indirect impact of the Clinton Global Initiative. As I and other leaders from the private sector depart CGI’s 12th and final Annual Meeting later this week, the important work and impact of our commitments will continue. Doing well by doing good – and valuing the integration of both business purpose and societal gains – is now an unstoppable force in best business practices and in modern philanthropy.

Image credit: Paul Morse/Clinton Global Initiative

Derek Yach, MBChB, MPH is Chief Health Officer at Discovery Vitality. He has been a full time employee of PepsiCo and has been on the Advisory Committee for the Clinton Global Initiative since 2006.

For Impact Companies, 'Exit' Is Not a Four-Letter Word

By Adam Wiskind

As a mergers and acquisitions advisor with an interest in serving the social impact community, I arrived at SOCAP16 seeking strategies to preserve the missions of social impact companies that go through a merger or acquisition.

I was surprised to discover that many impact investors and entrepreneurs haven’t given much thought to exit strategies. Or they believe exiting is antithetical to mission, and that exits involve private equity vampires swooping down on hapless impact companies, stripping them of their missions and selling them off to the highest bidder.

But one informative, hands-on session -- called Structuring for Impact without Relying on Exits -- stood out. It provided practical advice on creative investment terms, such as demand dividends and variable payment option loans which “patient” capital can use to structure investments that match certain types of impact companies’ limited ability to pay. Clearly these approaches are important when businesses create real world impact but less-than-market returns. However, the expectation that social impact must receive exceptional investment terms to be viable comes with the risk that more mainstream capital will not want to or be able to participate.

Furthermore, access to patient capital does in no way negate the need to plan for the eventualities of the future. There are many impact companies for whom planning an exit is not just a good idea, it is essential to deliver on impact goals and to protect the companies against the very loss of mission for which they fear.

An exit strategy is a contingency plan that is executed by an investor or business owner to liquidate interest in a company once certain predetermined criteria have been met or exceeded. It may be executed for the purpose of divesting from a non-performing investment or closing a business that is not generating sufficient returns. In this case, the purpose of the exit is to limit losses.

An exit may also be executed when an investment or business venture has met its profit (or impact) objective and for various reasons financial or otherwise the investors or entrepreneur no longer chooses to participate in the venture. It is wise to plan for both of these scenarios. Indeed, the very lack of disciplined exit planning that defines success and failure for social impact enterprises results in a great deal of wasted capital, Ned Breslin argues in the Harvard Business Review.

Michael Whelchel of Big Path Capital and Jeff Woodward of Taylor English Duma LLP, longtime participants in the social impact community, pointed to a growing portfolio of companies to that have exited successfully while managing to amplify their impact. Ben and Jerry’s, Honest Tea, Stonyfield Farm, and Plum Organics were all acquired, maintained their missions, and went on to have a significant influence on the mission of the acquiring company.

Their strategies provide a roadmap for others to follow:

Plan ahead

Successful exits don’t happen. They are planned, sometimes years in advance of execution. Take the time to set goals and strategies for exit; it will pay off in the end.

Most entrepreneurs only sell one company in their lives. Hire an experienced professional to help with the process so that during the sales process the entrepreneur and management team can focus on running the business.

Know your buyer

Most merger and acquisition failures are due to lack of cultural integration between buyer and seller. Spend time to identify mission-aligned investors and actively pursue them. Once potential investors have been identified work hard to understand their values and motivations.

Embed mission in the DNA of the company

Make mission core to the company’s brand and inseparable from the company’s product or service. Patagonia’s mission to “use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis” is evident in all of their marketing and the products that they make. Patagonia’s value as a company is its relentless pursuit of its mission, without it they are simply another outdoor clothing company.

Structure matters

Judy Wicks of the White Dog Cafe chain developed a unique structure to preserve mission during the sale of her company. Wicks retains ownership of the brand name and licenses it back to the new owner with a "social contract" that protects key aspects of the company's social mission. Failure to adhere to the contract would lead to a termination of the license.

Incorporating as a benefit corporation signals to potential investors the importance of preserving mission. This gives legal protection to directors and officers to consider the interests of all stakeholders, not just shareholders, when making decisions.

Another way to find investors who share the company’s mission is to turn employees into owners through worker cooperatives or employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). Employees are often best positioned to appreciate a company’s mission and to carry it forward.

The bottom line

While none of these exit planning strategies can assure that mission will be preserved through a merger or acquisition, it's fair to say that they will produce better results than not planning for exit at all.

Image credit: Flickr/Kevin McGill

Adam Wiskind, based in the San Francisco Bay Area, is an M&A advisor to lower middle market companies with revenues between $1-$50 million. Please contact him at [email protected] or linkedin.

Is ACA Succeeding At Promoting Workplace Wellness?

Rising healthcare costs are a national crisis. Healthcare costs have jumped from $634 billion in 1980 to over $3 trillion in 2014.

In an effort to reduce healthcare costs and improve outcomes, Obamacare, aka the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which went into effect in March of 2010, included regulations for employers who choose to offer workplace wellness programs like discounted gym membership, free flu shots or biometric screening for healthcare risk factors.

The language of these regulations was quite vague and unfortunately had the unintended consequence of incentivizing some bad programs. For example, the original language actually made it okay for companies to set different health insurance pricing based on wellness program participation, weight and smoker status.

"While group health plans and health insurance issuers in the group and individual market are generally prohibited from discriminating against participants, beneficiaries, and individuals in eligibility, benefits, or premiums based on a health factor. An exception to this general prohibition allows premium discounts, rebates, or modification of otherwise applicable cost sharing (including copayments, deductibles, or coinsurance) in return for adherence to certain programs of health promotion and disease prevention, commonly referred to as wellness programs." -- (FAQS ABOUT AFFORDABLE CARE ACT IMPLEMENTATION (PART XXV) April 16, 2015

Yikes! And an extremely vague definition of what a wellness program actually is only added to the confusion

"Under section 2705 of the PHS Act and the wellness program regulations, a health-contingent wellness program must be reasonably designed to promote health or prevent disease. A program complies with this requirement if it (1) has a reasonable chance of improving the health of, or preventing disease in, participating individuals; (2) is not overly burdensome; (3) is not a subterfuge for discrimination based on a health factor; and (4) is not highly suspect in the method chosen to promote health or prevent disease.6"The determination of whether a health-contingent wellness program is reasonably designed is based on all the relevant facts and circumstances."

This circular language was not super helpful for any benefits administrator looking to follow the law. Unsurprisingly, an industry of “wellness experts” quickly boomed, offering companies a one-stop shop for wellness programs and promising lofty financial returns like $3 in savings for every $1 invested. Many companies jumped in whole hog, offering things like discounted premiums for participation and specific health outcomes like achieving a certain BMI – which were unpopular and discriminatory.

EEOC enforces the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA). EEOC actually had to get involved and reel companies in. The more extreme programs weren’t exactly legal, and companies like Honeywell were even sued by the EEOC over discriminatory practices.

In 2016, EEOC issued new regulations to fix this wild west of wellness programs. The goal was to modify ADA requirements for workplace wellness programs “in a manner that reflects both the ADA’s goal of limiting employer access to medical information … and the ACA’s provisions promoting wellness programs.” (LINK)

These clarified a lot of the confusion around how these programs are supposed to operate.

While most of the gross privacy violations and demeaning program requirements have now disappeared, two big questions remain.

- Do these programs make people healthier?

- Do they save companies money?

Unfortunately, there are no quick fixes when it comes to health or money. But independent, third-party research demonstrates modest returns on both fronts – for folks who are willing to wait.

Larry Boress, president of the Chicago-based Midwest Business Group on Health, explained to the Chicago Tribune: “We've learned that ROI is not the correct measurement approach. Based on research and experience, the value of investment is a better approach. Some initiatives reduce costs in the short term, but there are lagging indicators that you won't see a difference for three to five years.”

He said that when employees learn how to better manage their health, they experience greater satisfaction and eventually their employers will save on healthcare costs. "But it may take years."

Wellness programs are certainly popular, especially among larger companies. RAND found in a 2012 study: “About half of employers with at least 50 employees, and more than 90 percent of those with more than 50,000 employees, offered a wellness program in 2012.” Researchers also found that employee participation varied highly with incentives: “Employers that did not use incentives reported lower participation rates and framing incentives as penalties was associated with higher participation rates. In the absence of incentives, employers reported a median participation rate of only 20 percent.”

Given that the new EEOC guidelines, released two years after this study, set stricter guidelines on incentives, perhaps we will see reduced participation rates in the coming years.

Do workplace health programs reduce costs?

RAND also found that these programs were not particularly effective at reducing costs or healthcare utilization: “Participation in lifestyle management programs was not associated with significant changes in overall [healthcare] cost or utilization.”

The RAND report did find improved health outcomes from employees who utilized telephone counseling, but noted it was quite expensive.

In short, wellness programs are not going to offer a quarterly return on investment, and they may even cost money over time. But cost may not be the best way to look at the impact of these programs. The Health Enhancement Research Organization (HERO) and Population Health Alliance (PHA) recently released a guide for measuring impact in a wellness program, and while the path to financial improvements is there, it’s no quick hop, skip and jump -- as the graphic at right aptly highlights.

The guide emphasizes that the ROI for wellness programs doesn’t come from revenue; it comes from avoided costs. By casting a broader net to include not only direct cost reductions but also items like “monetized improvements in healthcare service utilization” (i.e., choosing an urgent care center over an ER for immediate care) and “monetized improvement or prevention of lifestyle-related health risks,” like an improved diet or exercise regime, companies can accurately measure those cost savings and prove a return on the program.

Because these calculations are quite complicated, and detailed, they will be most useful to organizations where the financial return needs to be proven before a program can continue.

Many organizations understand intuitively that treating employees as whole people and offering benefits will reduce turnover and absenteeism and improve employee morale, and for them, detailed accounting won’t be necessary.

Johnson & Johnson has long been a leader in offering workplace wellness programs – since long before ACA went into effect, it should be noted. Harvard Business Review reported in 2010 that Johnson & Johnson’s workplace health programs achieved a two-thirds drop in the number of employees who smoke since 1995. The number of Johnson & Johnson work associates reporting high blood pressure fell by half.

Johnson & Johnson estimates that every $1 spent on its workplace wellness program has generated $2.71 in health cost savings. The company estimates $250 million in health cost savings between 2002 and 2008 achieved through its workplace health program.

We spoke to Lisa Blair Davis, vice president of international total rewards and global benefits for Johnson & Johnson, to better understand how the workplace wellness program has been so effective among a sea of mixed results. Blair Davis has been with Johnson & Johnson for over 24 years, and she was quick to point out that the company was not interested in a quick return.

“Workplace wellness starts with our credo,” she explained. In addition to putting customers first, the credo includes a special shout-out to employees:

"We are responsible to our employees, the men and women who work with us throughout the world. Everyone must be considered as an individual. We must respect their dignity and recognize their merit. They must have a sense of security in their jobs. Compensation must be fair and adequate, and working conditions clean, orderly and safe. We must be mindful of ways to help our employees fulfill their family responsibilities. Employees must feel free to make suggestions and complaints. There must be equal opportunity for employment, development and advancement for those qualified. We must provide competent management, and their actions must be just and ethical."

In that light, the worker wellness program becomes a means of fulfilling a larger mission, not simply a way to reduce costs. In fact, she underscored that it really wasn’t about costs at all:

"The biggest thing overall is that there is no overnight success. We look for long-term wins. That’s not just in worker wellness; it’s throughout the company. When you get hired, we look not just at how you’ll perform a role, but if we are a place where you can grow your career. We make long-term investments. My 24 years [of] employment is not unusual. While many companies want quick wins, short-term results – benefit comes over the longer term."

Worker wellness simply becomes a part of being a good employer. Over the years, Johnson & Johnson’s worker wellness program shifted based on the needs employees raise in an annual survey. Recent additions include a focus on stress-reduction, work/life balance and community engagement. “It’s holistic,” she explained.

To go back to the original question that kicked this article off: Is ACA succeeding at promoting workplace wellness? The answer is not really -- unless one subscribes to the "all press is good press" approach to crisis management. At least the controversies around ACA have gotten the word out about the fact that worker wellness programs can make for happier employees, if implemented correctly.

Image credit: Pixabay

Turning Ethical Investing into a Wall Street Disruptor

OpenInvest, a new investing platform that beta-launched at SOCAP16, aims to transform investing by putting the power of ethical investing into each investor's hand.

Sustainable investing is no buzzword – it has been over a decade since the first sustainability-focused investment firms and options emerged. Even as evidence has grown that sustainable investing is actually more profitable than investing in companies or industries with bad practices, it remained little more than a drop in the bucket compared to the vast sums flowing on Wall Street on a daily basis.

The flip side of sustainable investment – divesting from companies with bad practices, such as the movement to get universities to divest from fossil fuel companies, has also had limited financial impact. The leaders of this movement, in fact, acknowledge that its goals are more moral and social rather than financial.

Still, the immense social support for divestment shows that Americans are ready to put their money where they values are – if we can empower them to do so in an easy, effective way.

Enter OpenInvest. Its co-founder, Josh Levin, is not your typical startup founder. He previously worked for the World Wildlife Federation and has a deep understanding of the power of social movements to bring about substantial change.

“[At WWF], I saw how hearing from a customer base was powerful in getting companies to act,” Levin told TriplePundit. “[We're] never going to get things done without that groundswell.”

Though targeted corporate accountability campaigns have proved successful, they currently require massive investments in organizing and advocacy by civil society organizations. Ethical investing is, so far, only playing a tangential role. The problem, Levin told us, is that the current system is still controlled by large Wall Street banks and investment firms, which make it as difficult as possible for someone to invest their money ethically, trapping it in the existing ecosystems, under their control.

The other challenge is that existing ethical investment options are not tailored enough. That means someone who cares about, for example, renewable energy and healthcare access may find funds focused on one of these issues. But within each individual fund may be companies that don't align with your values, meaning your impact is being diluted.

OpenInvest's model is focused not only on creating a massive, one-size-fits-all fund, but also the exact opposite. The group hopes to take advantage of the massive growth in data-driven technology that is transforming how business is conducted around the world, for better and for worse.

We've all heard about Robo-Investing, funds that are now managed by super-computers using sophisticated algorithms. It is that same technology that OpenInvest plans to integrate and unleash to power ultra-customized, socially-conscious investing.

“Technology [now] allows deep customization in real-time,” Levin said. “By applying that to the financial space, we felt we could allow impact investing at the retail level.”

In practice, this means you can create your own personalized investment portfolio that aligns with your values. This involves integrating information from a half-dozen sources (with more to come) and allowing users to simply swipe and eliminate companies or even entire industries, from their portfolio.

The goal is not just better investing, but also engagement. Getting more people involved and empowering them through their investments will only make companies more responsive to their needs, Levin says.

“If we get to the point where the public is more engaged ... that is how we transform finance."

Image credit: Prawny via Pixabay