Stranded Assets: Preventing the Next Era of Climate Change

I first heard the term “stranded assets” at a Bloomberg event in New York City during Climate Week 2014. For me, the term conjured up images of homeowners and their dogs waiting atop roofs to be rescued during Hurricane Katrina. Yet that didn’t seem right for the context of the discussion, and a quick Google search set me straight: They were talking about coal-fired power plants that would be worth nada on Wall Street should a carbon tax change the market. (That was almost two years before Peabody Coal went bankrupt.)

Two years later at Climate Week NYC 2016’s Sustainable Investment Forum, stranded assets still seems to mean the same thing to investors – coal – and they mull it increasingly. The industry understands the term as holdings that need to be written down before the end of their expected life span. I heard the term from Federic Samama, deputy global head of Institutional and Sovereign Clients; Mark Campanale of Carbon Tracker Initiative; and Philippe Desfosses, CEO of the French pension fund Retraite Additionnelle de la Fonction Publique.

But, tell me, aren’t those 150,000 Louisiana homeowners who lost their homes from flooding last month stranded? What about the Ethiopian farmer who has lost everything from two consecutive years of drought – the worst in 50 years? And doesn’t Wall Street play a role in avoiding this future era of stranded assets?

You might maintain that insurance is where these losses appear in the financial ecosystem. But most of the impacted homeowners in Louisiana and those Ethiopian farmers were uninsured or underinsured for their flood and drought losses.

Ian Simm, founder and CEO of Impax Asset Management Group, said the experts in his firm who would feel climate extremes are the private equity portfolio managers. A situation where a few elements of a portfolio – corporations are hit by a weather extreme, delivering below-expected returns, which could take down a portfolio – and its manager with it.

BlackRock reports in its September 2016 white paper Adapting Portfolios to Climate Change that extreme weather events – think “climate shock” – trigger slower economic growth while an increase in temperature – think “climate stress” – decreases productivity. But I have yet to find a shift in the investors’ thinking that acknowledges a new era has dawned of assets stranded by the physical risks of climate change.

In an October 2015 white paper, The Price of Climate Change Global Warming’s Impact on Portfolios, BlackRock asked, “Do securities of companies most susceptible to physical and regulatory climate risks already trade at a discount to the market?” It answers its own question, responding, “We have not observed such a discount in the past – but could see one in the future.”

I hope BlackRock and its fast-followers continue to ask questions about that future as current and future physical risks become clearer and clearer. I imagine they’ll find so much risk in their portfolios that the sensible way to calibrate will be to invest in resilience that prevents more stranded assets in the future, turning those discounted trades into opportunities for portfolio growth.

Image credit: Flickr/maxstrz

Joyce Coffee is the president of Climate Resilience Consulting and works with leaders to create strategies that protect and enhance markets and livelihoods through adaptation to climate change.

Fukushima Radiation Now Extends through the Pacific Ocean

Ed. Note: Some of the information contained in this story is not verifiable. Author RP Siegel has penned an updated article, available here.

Some rather disturbing news came out this weekend about the impact of the nuclear catastrophe at Fukushima. While the incident took place five years ago and is no longer in the news, that does not mean it has been resolved. A recent report claims radioactive contamination from the accident has now spread across the entire Pacific Ocean, the massive body of water that covers nearly a third of Earth’s surface. Scientists now say the Pacific is at least five to 10 times more radioactive than it was when the U.S. began testing nuclear weapons there. Western Canada experienced levels of radioactive iodine-131 that were 300 times higher than normal background levels since the accident. Pacific herring have been found bleeding from their mouths, gills and eyes.

As the contamination made its way across the water, Oregon tuna were found in 2013 with radiation levels triple their previous levels. Starfish began dying off. The following year, California beaches recorded radiation levels that had increased by 500 percent.

As bad as that sounds, it gets worse. Remember the Deepwater Horizon oil spill? The broken pipe from the well gushed out roughly 2.4 million gallons of toxic crude into the Gulf of Mexico each day, posing a potentially lethal threat to the Gulf itself. There was a profound sense of relief around the world when the well was finally capped after 87 days.

But five years after the meltdown, radioactive waste is still pouring forth from the ruins of the Fukushima plant. Not just a little, but rather an estimated 300 tons of radioactive waste continues to spew into the ocean every day. The site, between the radioactivity and the heat, is still far too dangerous for humans or even robots to approach in an effort to try and contain the leaking cooling water that must continue to be circulated over the failed reactors, to prevent a catastrophic further meltdown.

TEPCO, the public utility that owns and is responsible for the plant, submitted a plan for decommissioning the facility, which includes dismantling the buildings, removing the fuel rods, and freezing the ground surrounding the facility to impede the flow of water. The company submits progress reports on a monthly basis to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

There are a couple of caveats here. First, TEPCO and the Japanese government have been less than forthcoming about the entire episode -- denying, for example, that a meltdown had actually occurred until two months after the fact. Misinformation is widespread. There are a lot of websites, either spouting complete hysteria on one hand, or other sites, such as this one, that claim that the whole thing has been blown out of proportion. They don’t deny that the radiation has spread as described above, but rather they maintain that the levels being measured are not yet harmful.

If you’re comfortable with that and feel ready to go ahead and start building more nuclear plants, as apparently the U.K. is, I’d think about that carefully. The U.K. is considering the deployment of dozens of small modular reactors (SMRs) that could be in place as soon as 2030. There are several of these planned in the U.S. as well. These new designs are expected to be considerably safer than previous plants, but then again, the previous generation were supposed to be virtually foolproof. But making them smaller would be a good idea, since that would likely limit the level of damage in the case of an accident.

Plenty of analysis shows that renewables, when paired with storage and a smart grid, will provide nearly all, if not 100 percent, of our electrical energy requirements. At the same time, it has been clearly demonstrated that all forms of highly concentrated energy, be it fossil fuels or nuclear, bear considerable downside risks. In the wake of the Fukushima disaster, Japan started to reverse the trend, which was moving away from renewables until 2012. There will likely continue to be some legitimate need for new conventional sources as economies transition, but we need to be careful to maintain absolute priority for clean, safe, renewable power before approving any additional nuclear, coal, or even natural gas plants, to be sure that these are not just the most expedient, or the most profitable for those that have the ear of whoever is watching the henhouse.

Image credit: IAEA Imagebank: Flickr Creative Commons

Past and future of sustainability with the RSA

HyperSolar Bumps the Hydrogen Race into High Gear

Imagine a zero-emission fuel that can be squeezed out of polluted water using a process powered by renewable energy. We may be closer to this reality than you think.

The company HyperSolar just completed the prototype phase for a new solar-powered system it says can "split" hydrogen -- that's the zero-emission fuel -- from dirty water, leaving cleaner water behind.

If you're new to the water-splitting topic this may sound a bit gimmicky, but it's for real. Similar technologies are under development by researchers around the globe. MIT and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory provide two among many examples in the U.S. And the U.S. Navy is testing a fuel-producing device based on seawater.

Hydrogen and renewable energy

Hydrogen is not a particularly energy-dense fuel, but it is abundant. And energy planners have long eyeballed it as a key resource for the global economy of the future.

However, referring to hydrogen as a "zero-emission" fuel under present circumstances is somewhat disingenuous. There are no tailpipe emissions when hydrogen is used in a fuel cell vehicle, for example, but the main source of hydrogen was (and still is) natural gas.

Using an electrical current to split water is another way to get hydrogen. But that process is not viable in a fossil fuel economy, at least not on a large scale. It requires a tremendous amount of electricity.

In the U.S., coal and natural gas still dominate the electricity production landscape, so that's a no-go in terms of climate impacts. The local impacts of fossil fuel extraction also make a case against sourcing hydrogen from natural gas on a large scale.

Now that the age of renewable energy is gathering steam, the hydrogen-sourcing picture looks much brighter.

Wind and solar now provide a pathway for powering the water-splitting process on a large scale without relying on the fossil fuel chain. In addition, the intermittent nature of wind and solar power has motivated the search for large-scale energy storage solutions, and hydrogen fits the bill.

In Europe, for example, policymakers are looking at wind-powered, water-splitting systems that use the existing natural gas distribution network to store and transport hydrogen.

HyperSolar and the hydrogen economy twofer

Conventional water-splitting requires clean water, and that dials up some important water resource issues. Pre-treating water also add complexity to water-splitting systems, bumping up costs.

HyperSolar is a good example of a next-generation solution. The HyperSolar system was engineered specifically to be deployed in untreated water. The result is a twofer: a zero-emission fuel and cleaner water.

That's an important advantage in the future energy market. In the electric vehicle sector, for example, batteries have already established a strong foothold. The water treatment aspect of next-generation hydrogen production could provide an added value that helps fuel cell electric vehicles to carve out a niche.

How does it work?

Water splitting can be accomplished in different ways depending on the source of the electricity.

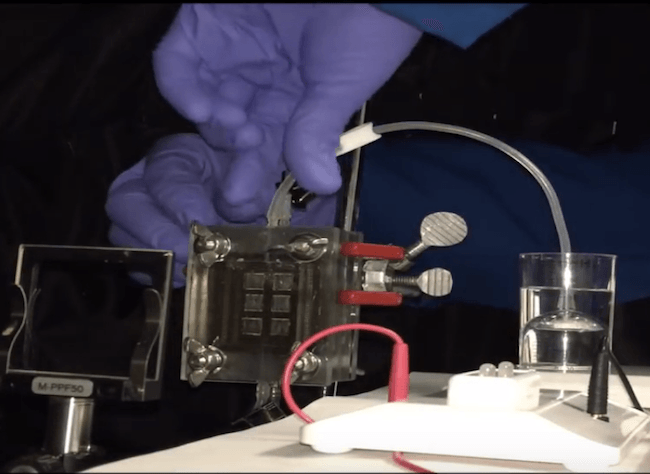

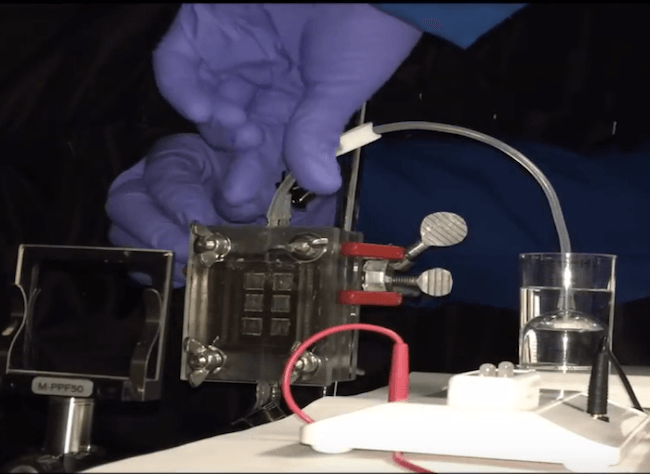

In a solar-based system like HyperSolar's, the water splitting system consists of a solar cell submerged directly in water. When exposed to sunlight, the charge generated by the solar cell results in a flurry of bubbles that are visible to the naked eye.

Here's a general description of from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory:

"The cleanest way to produce hydrogen is by using sunlight to directly split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Multijunction cell technology developed by the photovoltaic industry is being used for photoelectrochemical (PEC) light harvesting systems that generate sufficient voltage to split water and are stable in a water/electrolyte environment."

The HyperSolar system includes a protective coating for the catalyst, enabling the system to operate in corrosive water. The lifespan for the catalyst in the prototype is "hundreds of hours," the company says.

A high-voltage solar cell that mimics photosynthesis is a second critical element in the system.

Earlier this year, TriplePundit profiled HyperSolar and described these two aspects of the technology in detail, arriving at this conclusion:

"The combination of these two elements provide a distinctive economic advantage. But is it enough to relaunch the hydrogen economy? Only time will tell."

It looks like some companies are not letting any grass grow under their feet. The leading rail transportation company Alstom, for example, just unveiled a hydrogen fuel cell version of its popular diesel-powered engine. The new model is aimed at urban rail systems that are not likely to become electrified in the near future.

The U.S. lags behind Europe and Japan in the hydrogen economy, but it looks like that is about to change. Earlier this year the Energy Department described a "deep decarbonization" concept for the U.S. economy, and last month it issued a request for public input:

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has issued a request for information (RFI) to gather feedback on H2 @ Scale, which is a concept to enable wide-scale deployment of hydrogen to deeply decarbonize the U.S. electricity generation, transportation, and industrial sectors.

For now, the concept involves leveraging U.S. shale gas resources, but it appears that the Energy Department is moving swiftly beyond that. The agency is particularly interested in hydrogen production based on renewable energy.

Another potential power source for large-scale, non-fossil hydrogen production consists of reclaimed waste heat from nuclear power plants and other industrial operations.

As for the shale gas angle, the Energy Department makes it clear that continuing to produce hydrogen from shale gas would only count toward deep decarbonization if it is coupled with carbon capture.

If the cost of carbon capture is excessive, that could make renewable technologies like the HyperSolar system more competitive in the marketplace.

The next steps for HyperSolar involve scaling up, so stay tuned.

Image (screenshot): courtesy of Hypersolar via YouTube.

Foreign-Owned Farms Could Cause Instability Across Africa

Multinational companies are leasing enormous swaths of land across Africa, according to to a recent study. The result could be greater competition for water as increased shortages already impact local communities. This could cause greater risk of increased conflicts between citizens, wildlife and the local environment as the world struggles to feed a planet that could become home to 9 billion people by 2050.

According to researchers at Lund University in Sweden, foreign companies have already leased about 3 percent of land in Africa, about the same size as the U.S. states of Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma combined. Most of these leases run for a period of anywhere from 33 to 99 years, and the contracts generally lack any clear rules or limits on local water consumption. Critics have long said such leases amount to a “global land grab,” in which foreign companies and countries profit while local citizens are displaced and lose their way of life.

In order to estimate the impact a shift from the localized use of land to a system that tilts toward the production of lucrative cash crops, Lund University researchers developed models that gauge how much water is needed for various production systems. By comparing what areas can rely on local rain water versus land that would be reliant on irrigation, they pinpointed areas where an increased competition for water could cause water-related tensions between companies, communities and ecosystems.

Increased demand for food will exacerbate this problem in the coming years. According to the Brookings Institution, approximately 60 percent of the world’s arable land is in sub-Saharan Africa. The continent has become the last frontier for many of the world’s largest companies as they seek new markets for their products – and a base from which to source coveted raw materials such as timber and commodity crops like grains and palm oil. Add the interest in the region by countries such as China and the Gulf states in the Middle East, and Africa risks becoming a focal point of human rights violations as local communities discover they have less access to water -- or are even frozen out of lands on which they lived for generations.

Some companies say they are already cognizant of these challenges and are balancing the needs of local communities as they lease more land in Africa or contract with local growers. PepsiCo, for example, has invested in chickpea cultivation across Ethiopia -- which can provide a steady supply of this coveted foodstuff while training farmers, ensuring sustainable development and providing a bulwark against the risk of famine. Other food and beverage companies, including Unilever and Coca-Cola, say they have embarked on similar plans across the continent that is home to 1.2 billion people.

But the evidence suggests tensions are already brewing. Several foreign-owned flower farms were recently attacked in Ethiopia over allegations of human rights violations. And a recent investigation by the United Kingdom daily newspaper Independent suggests the demand for farmed fish is taking food out of the mouths of West Africans in order to produce animal feed for overseas companies. The Economist, however, suggests the real culprits of any African “land grab” are more affluent citizens from large cities who invest in the countryside. Nevertheless, the political sensitivities behoove foreign firms to mind the optics as they ramp up investment across Africa.

Both foreign governments and countries need to be transparent about their operations in a region where per-capita income hovers around $750. And in these societies that lack processes taken for granted in developed countries, like land titles and standards such as Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), must be defended and respected by governments and companies alike.

Image credit: Leon Kaye

Peter Thiel Gets Wakeup Call From U.S. Labor Department Over Racial Discrimination

Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel has been making headlines all year, but not in a way that's necessarily good for business. The latest party to chip in with some bad news is the U.S. Department of Labor. In a lawsuit announced last week, the agency accused Thiel's data-mining company Palantir of racially discriminatory hiring practices.

That's quite a smack in the face for a company that includes a diversity statement on its website:

"... Our community must attract and encourage people of diverse backgrounds, perspectives, and life experiences."We work every day to build a truly diverse workforce, and to foster an environment that is respectful and receptive to new ideas. We celebrate difference and diversity — of background, approach, and identity."

Palantir, PayPal and data mining

Palantir is a data-mining company co-founded by Thiel. He also chairs the company's board of directors.

That's not just a status title. BuzzFeed's long-form article about Palantir last July indicates Thiel's position on the board provides him with intimate knowledge of the company:

"Thiel ... knows as much about Palantir as virtually anyone, leading the company's close-knit board. While Palantir has grown in both revenue and employees, its $420 million in cash collections for 2015 amounted to less than a quarter of its customer bookings, raising questions about Palantir's ability to convert those deals into revenue," wrote William Alden of BuzzFeed News.

The company came into being in 2004, according to most sources, though one industry follower traced its official creation to May 2003.

According to that source, Palantir got its start by leveraging the anti-fraud algorithms of PayPal, another company co-founded by Thiel, to work with the CIA and other U.S. government agencies on matters of anti-terrorism and national security.

Perhaps partly due to its government work, Palantir garnered a reputation for secrecy among Silicon Valley watchers.

By 2009, the company expanded its scope in the crime-fighting sector -- counting the Los Angeles and New York City police departments among its clients. Palantir also works with the private sector on anti-fraud and security measures, and the company extended its reach from domestic business to the global market.

Palantir describes itself as a company that "makes products for human-driven analysis of real-world data."

Under the heading "we design technology to help institutions protect liberty," the company further elaborates:

"Analytic technology, especially in the hands of powerful institutions that hold large volumes of data, can pose serious risks to privacy and civil liberties. That's why we build privacy-protective capabilities into our products, help customers understand how to use them responsibly, and work with advocacy groups and the policy community on how technology can be used to protect privacy interests today and in the future."

Department of Labor sues Palantir

That reference to civil liberties is somewhat ironic, considering the Labor Department lawsuit accuses Palantir of deploying "a hiring process and selection procedures that discriminated against Asian applicants for software engineering positions on the basis of their race."

Further undermining the company's diversity statement, the Labor Department's press release indicates the agency is seeking legal relief only as a last resort, "after the department and Palantir were unable to resolve the findings through the conciliation process."

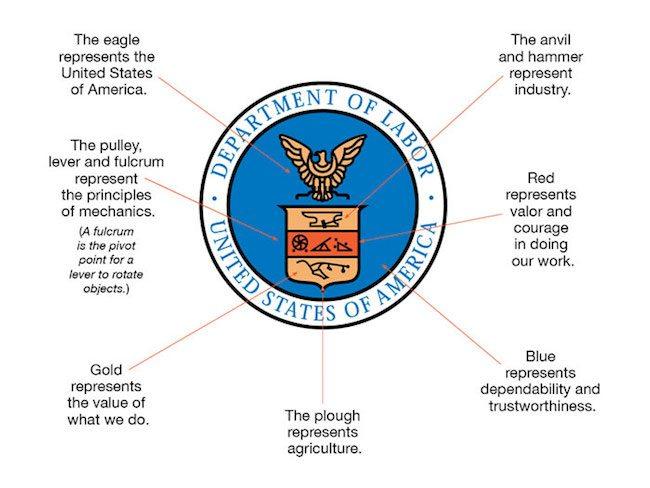

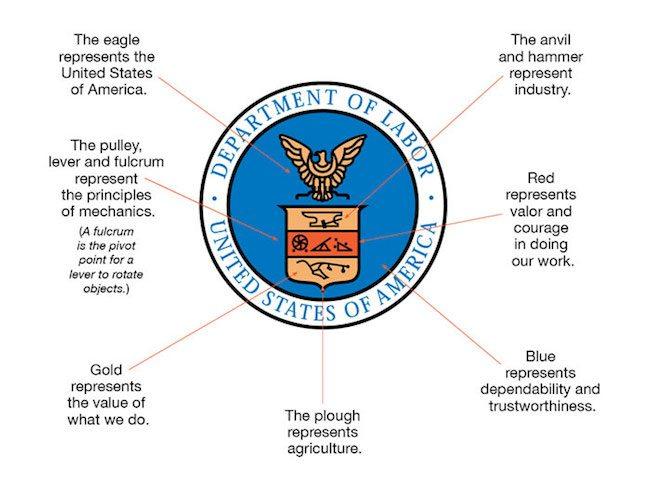

The lawsuit stems from Palantir's government work, which exposed the company to a review by the Labor Department's Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs.

That office enforces Executive Order 11246 of the Johnson Administration:

"On September 24, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, granting supervision of federal contract compliance to the Secretary of Labor, and creating the department’s first Office of Federal Contract Compliance. The EO ordered federal departments and agencies to impose non–discrimination and affirmative action rules in all federal contracts and federally–assisted construction projects ... "

The lawsuit, filed before the agency's Office of Administrative Law Judges, alleges that from 2010 or earlier to the present time, Palantir's Palo Alto facility used a hiring process for three engineer positions that "discriminate[s] against Asian applicants on the basis of their race."

The lawsuit lists specific instances, including this representative example:

"For the QA Engineer Intern position, from a pool of more than 130 qualified applicants -- approximately 73 percent of whom were Asian -- Palantir hired 17 non-Asian applicants and only four Asian applicants ... The likelihood that this result occurred according to chance is approximately one in a billion."

Thiel, Trump, accountability and Palantir

On the political front, Thiel remains a member of the increasingly exclusive club of staunch Donald Trump supporters, despite the candidate's proclivity for making racist statements and attracting racist supporters.

Thiel was a registered delegate for Trump in the primary season and nailed a prime speaking slot at the Republican National Convention in July. He made no further public appearances and issued no public statements for the rest of the summer, leaving political observers to wonder if he left the Trump fold.

However, it appears Thiel's support for the republican presidential candidate is as strong as ever. In an op-ed that seemed timed to support Trump's appearance at the Sept. 12 "Commander in Chief Forum," Thiel cogitated upon the need for a more forceful approach to labor management in American governance.

He concluded with an observation alluding to the candidate's well-known tagline in his long-running reality show, "The Apprentice:"

“One elementary principle is accountability: We can’t expect the government to get the job done until voters can say both to incompetent transit workers and to the incompetent elites who feel entitled to govern: ‘You’re fired.’”

Speaking of accountability, at the end of its press release the Labor Department dropped a hint that it is also seeking information on other possible labor violations by Palantir. The agency provided its toll-free helpline number (800-397-6251) and Compliance Programs website immediately after noting this area under its charge:

"... contractors and subcontractors are prohibited from discriminating against applicants or employees because they have inquired about, discussed or disclosed their compensation or that of others, subject to certain limitations."

That could be a reaction to widespread reports last spring, regarding a blanket "gag order" Palantir required of current and former employees who accepted an offer of stock compensation.

Stay tuned.

Image: via U.S. Department of Labor.

Got Purpose?: Analyzing Purpose-Driven Brands in the 21st Century

By Greg Doyle

At Cause Consulting, we define a purpose-driven brand as an organization that is guided by a deeper reason for existing, beyond profitability. This reason for existing, at its core, is driven by a desire to positively impact society. By no means are purpose-driven brands perfect. Rather they are brands that have identified a North Star that guides their work and adds value to society.

There has been much discussion around purpose as it relates to business strategy over the past few years. During his 2009 TED Talk, Simon Sinek famously stated: “People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.” And the Conscious Company and B Corp movements continue to gain momentum. Yet, the concept of brand purpose can actually be traced as far back as the 17th century when it was required that corporations contribute to the “public good” through specific projects and initiatives.

Even after the U.S. government removed the “public good” requirement needed for incorporation, our most historic business leaders carried on the concept. Co-Founder David Packard, in a 1960 speech given to Hewlett-Packard’s training group, stated the following on the concept:

“Purpose (which should last at least 100 years) should not be confused with specific goals or business strategies (which should change many times in 100 years). Whereas you might achieve a goal or complete a strategy, you cannot fulfill a purpose; it’s like a guiding star on the horizon—forever pursued but never reached. Yet although purpose itself does not change, it does inspire change. The very fact that purpose can never be fully realized means that an organization can never stop stimulating change and progress.”

The conversation around purpose-driven brands is now reaching a head. Companies are using their products and services as a medium to communicate their purpose.

Three key trends enable purposeful brands to succeed in gaining consumers’ share of heart, mind and wallet. First, the general public is becoming increasingly aware of, and engaged in, the social and environmental issues our country, and the world, is facing. The desire to rally behind critical issues will only continue, as we become more and more connected with each other and the current challenges facing local and global communities.

Secondly, as a result of this heightened level of awareness and engagement, consumers are using their purchasing decisions to reflect their values and the issues that they would like to make an impact on. In this process, they are demanding transparency and accountability from all brands, regardless of where they are on the “responsibility” continuum.

Lastly, a large portion of consumers, especially Millennials, are seeking purpose and fulfillment in their own lives and work. They are asking themselves tough questions about their future and the impact they would like to have on society.

The companies that have responded to these trends have gained recognition in the marketplace. CVS made headlines when it decided to stop selling tobacco in its stores and invest in programs that support consumers on their journey toward better health. On a smaller scale, brands such as Greyston Bakery -- with its credo “we don’t hire people to bake brownies, we bake brownies to hire people” -- are being recognized for the investments they make in their employees and communities. Regardless of whether the organization is a Fortune 500 company, social enterprise or B Corp, the brands that are receiving the most attention from consumers are those that authentically invest in a better world.

On perhaps the largest scale, Unilever made bold commitments to make “sustainable living commonplace” through its Sustainable Living Plan and its goal to double the size of the business while cutting its environmental footprint in half. According to the company’s Sustainable Living Plan annual progress report, about half of Unilever’s growth in 2015 came from its sustainable living brands, which grew 30 percent faster than the rest of the company’s business.

Is there a business case for companies to pursue purpose? We know that when a brand satisfies the wants and needs of consumers, there will be economic benefits that are realized for the company.

However, we also know that consumers are increasingly evaluating the societal impact of their purchasing decisions. What we are seeing is that the brands that authentically pursue their expressed purpose will be the ones that experience economic gains over the long-term. Brands that decide to position themselves as purpose-driven purely for the immediate potential business benefits won’t experience sustained results.

Looking ahead, the role of purpose-driven brands in the marketplace will only continue to rise. Currently, purposeful brands are seen as exceptions rather than the norm. However, in order for brands to thrive in the future, purpose will become required as a result of increasing pressures from employees, consumers, investors, competitors, governments and communities.

Stakeholders will not only be interested in an individual brand’s vision for a better world, they will be evaluating brands on the results their social impact programs and initiatives are having on the most critical issues within our society.

Image Credit: Flickr/Chris Blakely

Greg Doyle is an Associate at Cause Consulting, a strategy and communications firm that enables companies to simultaneously strengthen business + impact society.

Laurels for Credit Raters: Levers of Change in the Climate Adaptation Market

The voices and actions of the financial industry are critical to change capital market policy and practice change. That's why I’m thrilled credit rating agencies are seizing their role as levers of change in the adaptation market. Consider these three examples of their newfound interest:

- Standard & Poor’s explicitly weighs adaptation in its new Proposed Green Bond evaluation tool based on a scoring system that encompasses governance, transparency, mitigation and adaptation. This is noteworthy since a clear distinction exists in the market with response to rating, and that S&P even includes adaptation in its approach serves as a market signal. The main component of its resilience assessment, as proposed, is the ratio of the resilience benefit relative to the financing derived from the bond's proceeds.* S&P invites comment on its proposal here.

- In the same communication, S&P proposes an Environmental Social and Governance risk exposure assessment that includes climate change impacts.In what I consider an encouraging element, S&P gives climate risks a separate category from water use/scarcity. This proves notable since Wall Street tends to presume that the physical risks from climate change center on the shocks of extreme weather. Water scarcity, indeed, is a chronic stress exacerbated by climate change.

- In its proposed ESG assessment tool, S&P acknowledges the differences in the time horizon of risk. It defines medium-term risk as two to five years and long-term as beyond five years. I’ve written before that differences in timescale between adaptation projects and investment horizons presents one of the major challenges to engaging the investment community in climate adaptation. While climate has an impact on investment portfolios today, impacts are expected to worsen a decade or two out. So the “beyond” in S&P’s proposed methodology serves as a crucial acknowledgement of the future climate impact and responsibility ESG should acknowledge and embrace.

S&P is not the only rating agency moving into green bond ratings. Moody’s preceded S&P with its own Green Bonds Assessment Methodology that is notably lighter on the adaptation evaluation.

It’s been a red-letter year for the credit raters. So, what should they do next?

- With S&P Global Indices U.K.’s pending acquisition of environmental data provider TruCost, it is in a position to do more of this better. For instance, what if next year its Green Portfolio Analytics “2 Degrees Generation Mix” scorecard is matched with a similar dashboard for adaptation, allowing investors to consider how to diversify their portfolios into adaptation?

- Similarly, its Green Portfolio Analytics – that presumes a 2-degree increase in temperature as the company seeks an energy mix that decreases greenhouse gas emissions – should embrace the commonly understood 3.7 degree temperature-increase scenario for evaluating portfolios’ physical risk from climate change.

- It could modify the green bond tool as others in the marketplace develop better ways to measure adaptation. Actually, this is a major initiative of, among others, the Global Adaptation and Resilience Investment work group, of which I am a participant. Those using the analytics may balk that a change makes for inconsistency in year-to-year evaluation. But, hey, it’s experiment time, and every year that the score is weaker than it could be represents a year of lost opportunity to finance more resilience projects.

Kudos to the credit rating agencies for giving us much to weigh. Now, onward with your attempts to create the next market mover in your market research.

To encourage your comments, this is an excerpt on S&P’s proposed adaptation measure:

“Regarding adaptation projects, we propose the environmental benefit to be based on the increase in resilience of the covered geographical area or asset base. The main component of our resilience assessment is proposed to be the ratio of the resilience benefit relative to the financing derived from the bond's proceeds.Image credit: Flickr/Alan Kotok"We propose to calculate the resilience benefit as the reduction of the expected financial, humanitarian, and ecological damages caused by the natural catastrophe, and the changes in weather patterns projected under climate change the infrastructure is designed to protect against over the targeted period.

"To determine the resilience benefit, we would propose to review the analysis already performed by the technical advisers to the project as a part of the design of the resilience infrastructure to assess the cost-benefit of the project. In addition, we propose this category would incorporate our view of the adequacy of the third party data and assumptions used to determine the resilience benefit.”

Joyce Coffee is the president of Climate Resilience Consulting and works with leaders to create strategies that protect and enhance markets and livelihoods through adaptation to climate change.

Trump Picks Climate Change Denier for EPA Head

Nothing presidential candidate Donald Trump has done recently is status quo. And his rumored pick for head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should he be elected certainly affirms his love for upsetting the apple cart.

His choice, reports the Washington Post, is Myron Ebell, best known for his aggressive defense of the oil lobby and his staunch insistence that scientific assertions linking climate change to human activity are "flawed." Ebell is the director of energy and global warming policies for the Competitive Enterprise Institute and the chair of the Cooler Heads Coalition, a consortium of some two dozen or so organizations that echo his disdain for current climate change policies.

Those who remember the early days of the George W. Bush administration will likely recall Ebell's legacy. According to Heartland Institute, Ebell was labeled the "Villain of the Month" by the Clean Air Trust in 2001 for convincing a wavering Dubya not to regulate carbon emissions.

"This is a colossal mistake," Ebell said in regard to Bush's consideration of new regulations that would have required a tighter cap on CO2 emissions. ''If they persist, there will be war.''

In the end, the Bush administration backed down, to the dismay of both environmental organizations and some energy companies that pointed out the administration had a "real shot" at pushing legislation through if it just didn't call CO2 a "pollutant."

But Myron Ebell and those who saw new regulations as a threat to the oil industry refused to compromise. Regulations that would have started the path to decreasing carbon emissions sooner would have until another presidency.

So, if Trump's aim is to unravel the regulations the Obama administration put into play and remove the EPA's influence over the oil and gas industry, he picked the right man in Ebell, Andrew Revkin, Pace University's Senior Fellow for Environmental Understanding, wrote in the New York Times.

"Ebell is really the perfect man for the job if Trump plans to carry out his campaign pledges to boost oil production even more than has already happened just based on the market, and to gut the EPA."

Ebell's own quotes are begging for a sound-bite. He went on record to suggest "the so-called global warming consensus was not based on science, but was a political consensus." He suggested that "as previous studies have concluded, the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets are probably thickening rather than melting" -- an assumption that has been proven false. In 2013, he also suggested that regulating carbon emissions would result in inadequate options for energy -- a point that also hasn't shown to be true. "The [regulatory] policies being promoted are insane … If you believe energy poverty is a good thing, you should support controls on carbon emissions. But most of the world disagrees with that," Ebell wrote.

Myron Ebell's perspectives toward global warming and his intense focus on shielding corporations from stringent regulation has many environmentalists worried. But it is the inaccuracy of the claims with which he defends his position that perhaps should be most concerning. And there Revkin has a solid point. Ebell would be a perfect choice for an administration that doesn't care about accuracy of claims or the legacy those inaccuracies will leave the next generation's children, so long as industry profits are realized.

Flickr/TexasGOPvote.com

How a New Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Can Help Haitian Kids

Haiti is the poorest country in the western hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. It had a per-capita GDP of only $846 in 2014. It’s also a country that witnessed tragedy on a large scale when an earthquake struck in its capital, Port-au-Prince, in 2010 -- killing over 300,000, according to government estimates. One company is now looking to help Haitians better their lives.

That company is Thread, a Certified B Corporation that transforms plastic bottles collected by Haitian and Honduran people into fabric. Thread recently announced its new Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) Commitment to Action to address the problem of child labor in global supply chains. Through partnerships with Timberland, HP, Team Tassy and ACOP (the Plastic Collectors Association), Thread’s commitment will help improve the lives of about 300 Haitians, 200 of whom are children. Through the partnerships, programs will provide educational opportunities, job training and medical care for the Haitian communities of Molea, Menelas and Port-au-Prince.

Thread expects to invest $300,000 in monetary and in-kind donations by December 2019 through partnerships. The money will be used to provide detailed field assessment, wellness exams, healthcare services and building a career support network in Haiti.

Timberland and HP plan to source materials from the collection system in Haiti, in addition to joining the Commitment to Action. Timberland will launch a collection of bags and shoes made with Thread Ground to Good fabric in spring 2017. HP will use the materials to manufacture inkjet cartridges.

“The very bottom of the supply chain is where people are the most vulnerable,” Ian Rosenberger, founder and CEO of Thread, said in a statement. “No longer is it okay to ignore the issue because it’s difficult to talk about. We’re proud to be working with great partners like Timberland and HP to find a solution in Haiti that can change our global understanding of dignified work.”For the “first few years” Thread worked in Haiti, child labor was not a problem, Kelsey Halling, director of impact for Thread, wrote in a blog post last week. Thread “had a small and close-knit enough collection network” that prevented child labor from entering its supply chain. The company also has a Code of Conduct and Child Labor Avoidance Policy. But Haiti is an extremely poor country, so “these policies don’t always hold up,” Halling wrote. Last year, Thread expanded its supply chain in Haiti, which made it imperative to address child labor and began to partner with ACOP. In April, Thread approached the CGI about making a Commitment to Action -- which requires specific timelines, measurable goals and metrics, and annual progress reports.

Beyond Thread's supply chain, child labor is a big problem in Haiti. The country has a restavèk system which the nonprofit organization Free the Slaves describes as a “system in which Haitian children from impoverished homes are sent by parents to live with other families and work for them as domestic servants.” The children work as many as 14 hours a day for no pay. An estimated 150,000 to 300,000 children are part of the restavèk system.

The term restavèk in Haitian Creole means “to stay with.” It is now “one of the worst names to be called in Haitian society,” according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). The system began as a way to send children to “live with wealthier relatives in the city” so they could have a better life. But the system deteriorated and is now a “form of domestic trafficking and modern day slavery,” the ILO says.

Through its Commitment to Action, Thread is highlighting a major problem in Haiti. And through its partnerships, the company is working with families to give children access to education. That is something that can’t come soon enough for Haitian children.

Image credit: Flickr/International Disaster Volunteers