The Truth about Water and Cotton: It’s Complicated.

Cotton has a reputation for being "difficult," water-wise. Numerous non-profits and global media outlets such as The Guardian have laid blame on it for dwindling water resources in places like India, or for the environmental devastation in the Aral Sea. The truth, as is often the case, is not so cut and dried. In fact, cotton is downright drought tolerant and there are numerous ongoing efforts to improve cotton's water footprint across the board.

If cotton is not such a grotesque water hog, why the erroneous conventional wisdom? According to Ed Barnes, Senior Director for Agricultural and Environmental Research with Cotton Inc, a U.S.-based industry research and lobbying organization, quite often, it is guilt-by-association.

“Cotton naturally is very heat and drought tolerant,“said Barnes. “The plant...has always grown in very harsh environments. When you have a crop that is adapted to hot and dry climates, then it is growing in areas that experience water scarcity.”

Understanding where cotton is being grown is key to both understanding its water footprint, and also developing strategies to improve it.

“There all these complexities,” said Laila Petrie with the World Wildlife Federation’s Global Partnerships Team. “Is cotton being grown in a water-scarce area? Is there not good water governance?”

Even factoring all this, cotton – as one of the world’s most important agricultural products – does effect water scarcity in certain parts of the world, with sometimes negative impacts.

“There is a correlation between cotton and high irrigation, and there’s a high correlation between cotton growth and water scarcity and high water risk areas,” said Petrie.

Still, putting all the blame on the cotton plant is misguided. While farmers bear some responsibility, things like global warming and lack of oversight are beyond their control.

For example, the Aral Sea. While it is true that cotton farming was scaled up around Central Asia by the then ruling Soviet Union Government, it was the diversion of rivers away from the landlocked sea for unsustainable irrigation, all for quick cash from cotton exports, that was to blame for the disaster.

“The Aral Sea is a real tragedy of modern times,” said Barnes, “But there was nothing intrinsic about cotton that contributed to that problem.”

The truth is, we need cotton. As a product, it has numerous advantages. It is durable, recyclable, and provides livelihoods to millions. It’s main competitors – synthetics such as polyester, or leather – are rife with sustainability challenges as well. Cotton is an essential part of the global economy, and that is not changing anytime soon.

“Water is not a cotton problem, it’s a world problem, and none of us have really cracked that. It just so happens that cotton production is correlated with areas that have challenges,” said Petrie.

Thus, to blame the cotton plant alone would be a folly, and ignores the important role that technology, good governance, and proper farming techniques can play in making the crop more sustainable. In fact, Cotton Inc is working directly with farmers to provide better tools to help them make smarter water decisions – and seeing real results.

“The trend over the last 30 years – for every inch of water we use in irrigation, we’re getting more cotton,” said Barnes. “We’re finding over a 70 percent increase in lbs per inch of water.” And new technology, including the growing power of data, is making things ever better.

“One of our big pushes in the last five years is use of sensors in the field to measure the soil or the plant to see if it needs water,” said Barnes. They hope to have a national app for farmers next year that taps into sensor data, and data from the national weather service, to better equip farmers with the information they need to reduce water usage.

WWF is also working with partners – including Tommy Hilfiger, American Eagle, and numerous other global brands – to improve cotton through the Better Cotton Initiative. Their goal is to make global cotton production better for the people who produce it, better for the environment it grows in and better for the sector’s future, by developing Better Cotton as a sustainable mainstream commodity.

This means understanding that cotton’s life-cycle water usage and consumption, however, is not just what happens in the fields. Throughout the entire supply chain water is used, whether it is processing, printing, or even consumers washing and drying cotton products at homes across the world.

“Not much visibility from one end to another,” said Petrie. “There are 20 steps between the brand and cotton field. Cotton is traded as a commodity which means its hard to trace without a lot of effort.

This is a fundamental challenge for the industry.”

Both Cotton Inc, and WWF, have commissioned extensive, detailed reports and studies to figure out the whole picture of cotton’s water footprint, because unless we truly understand cotton at every phase of its, we can’t make it sustainable. In a future piece, we’ll look at the entire supply-chain water impacts of cotton to better understand the big picture.

Photo Credit: Mike Beauregard via Flickr

The Quick & Dirty: Time to Call BS

Most of us in sustainability (CSR, citizenship, social change, activism etc) are shell shocked. Donald Trump is the President-elect for the United States of America. I am not going to tell you how sick that is and how sick that makes me feel. What I want to know - what are we in this space going to do about it? How are we going to win this game of making the world a better place in a world of President Trump? I have a few ideas...

Let's start by calling BS when we see it. I am tired of seeing rankings and awards in this space dominated by fossil fuel companies and crappy fast food joints. That is just simply not good enough. We measure how companies reduce their impact and applaud them for that. It is a hollow victory when their biggest impact - their products or services - is in direct opposition to what we are trying to do. Not every business is equal and it is time we acknowledge that and call it as it is.

Let's call BS when companies claim leadership in our space but the value chain says otherwise. And I am not talking about the obvious wrongs like child labor or conflict minerals. Those are already called out. I am talking about the other parts of the supply and value chain that remains mostly hidden. Let's look at the banks these "leaders" use. Let's see what membership they signed up for. Let's judge the lawyers and lobbyist they hire. The politicians they support. And let's call out the PR, advertising and communications agencies they pay to convince us they are so cool. You can't be taken seriously if you hire the same agency employed by major fossil fuel companies or climate deniers.

Let's call BS on the incrementalism that has taken over our thinking. We measure and report to GRI as if that is some holy grail. It is a measurement tool not a strategy. We applaud ourselves for turning off the taps and switching off the lights. Business thrives on risk but somehow we refuse to take risks when it comes to creating the world we need for better business and a better society. This is not leadership. This is incremental nonsense. This is not how we stop the tide. This is not how we reverse climate change or deal with any of the largest challenges we face as a world.

Let's call BS on crappy communications. We absolutely suck at communicating. We are the most uninspiring lot of experts ever. We navel gaze and slap our own backs. We go to conferences where most of the sessions make us fall asleep. We put out ads that are boring and silly. I took a picture of one I saw at SFO about how they reduced their energy use. Really? This is as bad as it gets. A figure that no consumer understands or will feel inspired by and a reference to a lightbulb that isn't even the highest standard out there anymore. It's kicking the Kicking The Puppy approach and doesn't work. Not for the change we need.

I'll start calling BS with my industry. Just this week I got an ad for a major PR agency in my Facebook feed raving about the latest PR award they won. Really? This is what you stand for and then you want to say you somehow make the world a better place? BS. You can't work for Koch Industries AND work in this space as a respected agency. Your goal is either to create a more just, equitable and sustainable world or not. You pick. But don't fool yourself about your role in this space. Be comfortable with who you are and be true to who you are but let's not fool ourselves that all agencies are the same when it comes to this.

It doesn't mean incremental isn't needed. It doesn't mean that you can't be "just a PR agency." Those are all good. It's just not what we need for the big shifts that we need in this world. We need to make the big plays. The moonshots. And we need to call BS on those who distract us from that or who hold us back.

Now I will go back and cry a little bit more. President Trump... Damn. Time to wake up.

Migrant Workers Widespread in Food Supply Chain

By Annabel Short

We live in a world on the move. According to the UNHCR, the rate at which people are being forced to leave their homes (24 people a minute) is four times greater than a decade ago. Meanwhile, even higher numbers are responding to the forces of globalization and choosing to migrate for work opportunities. The ILO reports that there are over 150 million migrant workers globally.

Eleven percent of these individuals work in agriculture. Competition within the global food industry means many rely on cheap labor on farms and in food-processing factories. Migrant workers in all regions, many of whom are undocumented, are willing to work for far less than the local workforce. Whatever the extent of xenophobia these workers may face in their host countries, the economics mean that they will still migrate for work, and unscrupulous labor brokers will take advantage, passing the savings on to corporations.

Within the U.S., for example, over 70 percent of farm workers are immigrants. In this context, and amid rising anti-immigration-rhetoric, food companies need to acknowledge the large numbers of migrant workers in their supply chains – both on farms and in food-processing – and the specific vulnerabilities they face. This includes racism and discrimination, but also hazardous working conditions, and at the worst extreme, situations of modern-day slavery. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers has estimated that in the U.S. alone, around five percent at any given time are subject to forced labor: numbers in other countries can be much higher still.

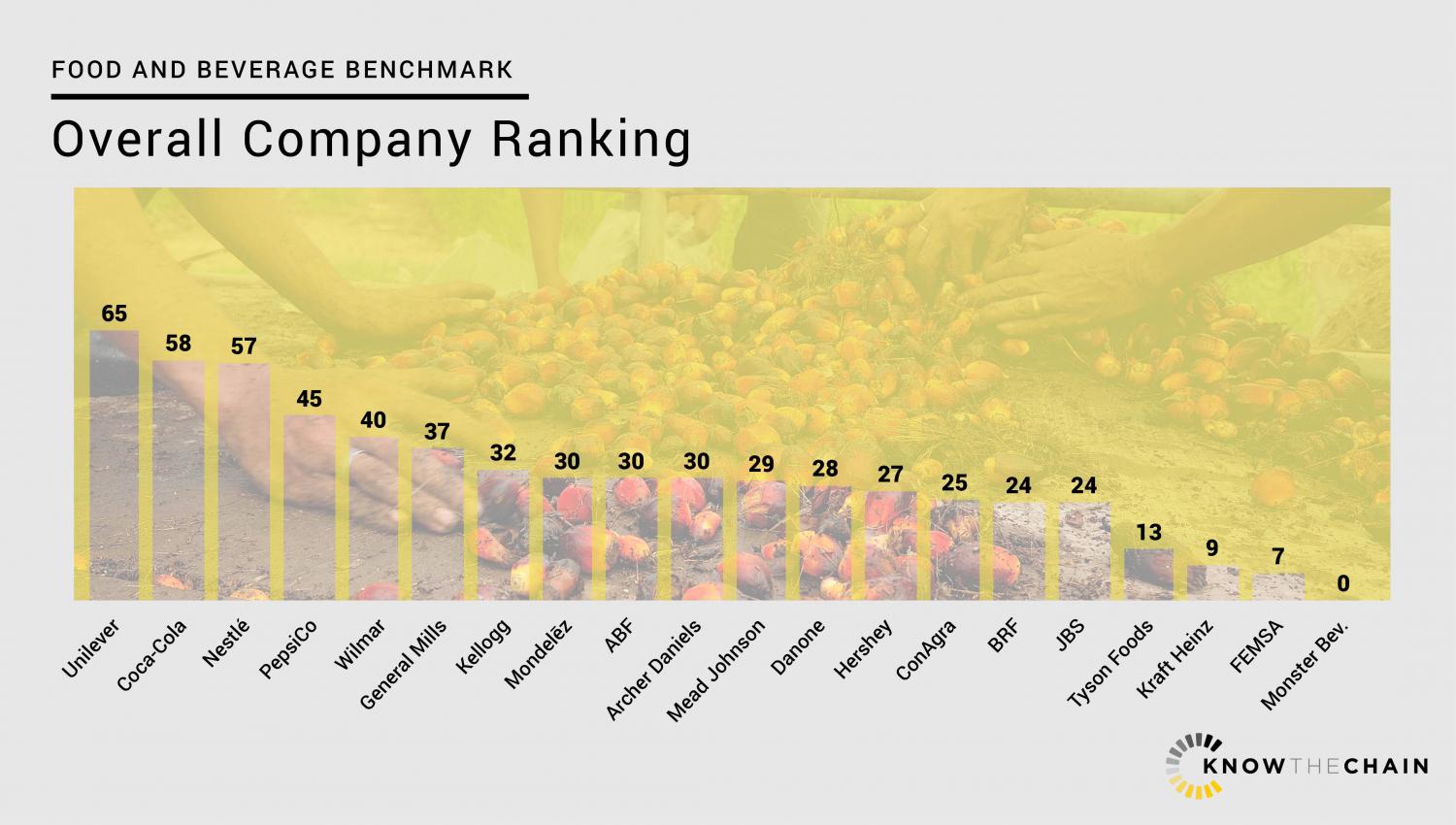

A new benchmark by KnowTheChain of the world’s 20 largest food companies has found that while they are aware of the risks of forced labor through their supply chains, only a handful are taking action to address it. Three areas in which food companies need to step up their game are recruitment, tracing their supply chains to the level of commodities, and worker voice.

Recruitment

It is through the recruitment process migrant workers are particularly at risk of falling into forced labor: having to pay fees for their jobs then working for long periods of time just to get to the point of paying off their debt.

A Wall Street journal exposé of conditions on palm-oil plantations in Malaysia supplying international companies, for example, included the story of Mr. Rubel, a young Bangladeshi man who was promised work opportunities in Malaysia. After being smuggled in a fishing boat where he witnessed fellow migrants dying from lack of food and water, and after his father was forced to pay the smugglers $2500, he found himself working on a plantation, without being paid.

Recruitment was the lowest-scoring of the benchmark themes, with companies scoring an average of 10/100. It is encouraging, however, that two of the companies in the benchmark, Unilever and Coca-Cola, have joined the “Leadership Group for Responsible Recruitment” and adopted relevant practices to address this issue – others should follow suit.

Traceability

Food companies have complex and fragmented supply chains, which creates challenges for oversight. The benchmark found that while several companies have begun to trace their supply chains – an important step in identifying the risks of forced labor – this so far tends to be limited in scope to high-profile commodities such as palm oil and sugar. Companies now need to extend their tracing efforts to other commodities where forced labor can still occur, such as beans, nuts and seafood.

Worker voice

One of the most effective ways to prevent and remedy situations of forced labor is to ensure that workers are able to organize and effectively raise complaints. As the precedent-setting work of the Fair Food Program has highlighted, worker-driven, market-enforced human rights programs can be extremely powerful in driving tangible improvements in working conditions. Yet worker voice was the second lowest-scoring theme in the benchmark, with limited examples of direct engagement with workers, effective access to grievance mechanisms, or steps to enable workers to organize in contexts where there are regulatory barriers to them doing so.

The industry has a responsibility to recognize migrant workers in their supply chain and treat them as more than a cheap supply of labor, taking practical steps to prevent them from being trapped in modern slavery.

Annabel Short is Deputy Director of Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, based in the New York Office. She overseas the Centre's work on labor rights and regional programs in Asia and the Middle East, working closely with the Centre's five researchers based in those regions. The Resource Centre is one of the partner organizations in KnowTheChain, together with Humanity United, Verite, and Sustainalytics.

Jellyfish, a Sustainable Source for Paper Towels and Diapers?

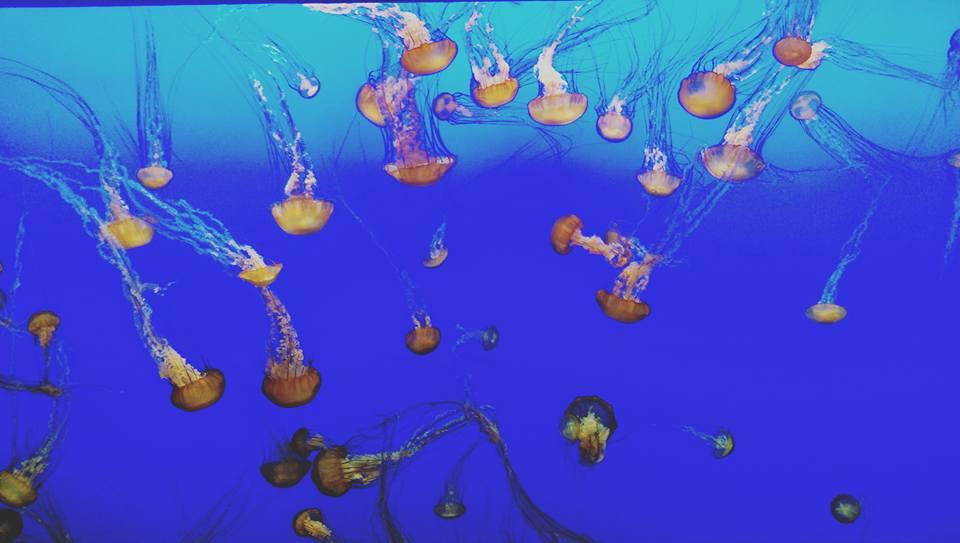

The science behind the surge in jellyfish populations across the world’s oceans is under debate. Nevertheless, whether the leading causes are overfishing, climate change, acidification or pollution, jellyfish blooms are on the rise and have wreaked havoc from Australia to Scandinavia. One writer has even suggested jellyfish themselves are helping to fuel climate change, as the waste they generate creates more carbon dioxide, which reduces the populations of plankton, the microscopic-sized organisms critical for their role in the removal of CO2 from the world’s oceans and atmosphere.

Meanwhile, jellyfish clog pipes connected to a nuclear power plant in Sweden, shutter aquaculture operations and have made it difficult for natural fishing stocks to recover. Organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium have accelerated research and launched sites, such as the “Jellyfish Watch,” to track this ongoing threat to local ecosystems and marine life, but so far this ongoing problem has proven to become too large to control.

One start-up in Israel, however, has seen an opportunity in the jellyfish blooms that have been insidious across the Mediterranean Sea in recent years.

Cine’al, based in Tel Aviv, believes it has found a use for the jellyfish that suddenly wash ashore in massive numbers, or as in the case several years ago, compromised a nuclear plant’s pipes in the northern coastal town of Hadera.

Jellyfish are highly absorbent, as they are comprised of 90 percent water. This absorbency inspired Shachar Richter of the University of Tel Aviv to test them out for their usefulness in consumer products. The result is a material that Richter developed called “hydromash,” a material Cine’al claims is more effective at absorbing materials than conventional paper-based products. The dried jellyfish are churned into a fibrous material that is naturally antibacterial, flexible and can help skin heal quickly when used in products such as bandages. Better yet: when hydromash is used in disposable diapers, Cine’al claims that these discarded products can biodegrade in 30 days or less.

Contrast that rate with that of conventional disposable diapers, which according to most sources, take anywhere from 250 to 500 years to decompose. As one of Cine’al’s executives explained to a local newspaper, if this hydromash process can scale, the long term result will be a win-win. Jellyfish are washing up on shores, leaving a negative impact on the tourism and aquaculture industries; meanwhile, diapers are taking a significant amount of space in landfills.

The harvesting of jellyfish could also complement the global pulp and paper industry. While the vast majority of paper products come from managed forests, a growing population worldwide always leaves the door open for additional deforestation. The trick, however, is market acceptance and getting over the “ick” factor. And forget about growing demand for vegan products, as an animal-based paper towel, bandage or tampon will be a non-starter for some consumers.

Nevertheless, a solution is needed, as the evidence suggests jellyfish blooms will not recede anytime soon. Some observers have suggested harvesting more jellyfish as a food source, as they contain some nutrients such as collagen and amino acids. Several Asian cuisines showcase this translucent creature: a shredded jellyfish salad is a mainstay side dish in Korea. Other companies have harvested jellyfish for use in beauty products, but those anti-aging creams and lotions have not caught on with many consumers.

The reality is that the world needs to take far more aggressive action on our oceans and the global seafood industry if society is going to avert a massive marine disaster. But this change in the world's oceans also opens up new business opportunities – which can contribute to the healing of the seas in the process.

Image credit: Leon Kaye

Oklahoma Cheers New Wind Power Project, Boos Earthquakes

Oklahoma's earthquake problem has cast a pall over its oil and gas industry, but there is a bright spot in the energy picture. The local wind industry is set for boom times as pre-planning moves forward on the Plains and Eastern Clean Line, a 4,000 megawatt transmission line that will bring power from Oklahoma wind farms to points east.

In the latest development, global clean energy leader GE has signed on to provide an important element that will help ensure that the wind-powered electricity can compete on cost with fossil fuels.

Wind power to compete with fossil fuels

GE will be providing three converter stations to the project. Their task is to convert the AC current from wind farms into DC current, then back to AC for pickup by local grid operators.

If that sounds like a lot of work for nothing, it's not. Long distance, high voltage transmission lines operate much more efficiently when carrying DC current.

Even though the three converter stations add up-from costs to the project, the result will be a long term savings in the cost of wind energy. In a conversation with me last week, Andrew Goodman, the Plains & Eastern project manager for GE, anticipated that the cost of electricity from the new transmission line would be competitive with fossil fuel costs.

So, why the whole AC-DC thing? As explained by the Department of Energy, DC (short for direct current, because it runs in a single direction) was the original form of electricity developed by Edison. By default, DC was the standard form in the earliest days of electricity.

Sooner or later a competing variety was bound to come along, and it did. Tesla (the inventor, not the auto maker), came up with AC -- alternating current -- which lends itself more easily for conversion to higher or lower voltages.

On an interesting historical note, the "current war" timeline includes this tidbit about the competition between Edison and Tesla, as demonstrated by the 1893 Chicago World's Fair:

General Electric bid to electrify the fair using Edison’s direct current for $554,000, but lost to George Westinghouse, who said he could power the fair for only $399,000 using Tesla’s alternating current.

GE soon jumped on board the AC train, and AC has remained the current of choice in the U.S. almost to the present day.

That's "almost," because solar cells, electric vehicles, LEDs and other new clean technology are designed to run on DC current.

And now, as the Energy Department points out, things have come full circle:

...methods are now available for converting direct current to higher and lower voltages. Since direct current is more stable, companies are finding ways of using high voltage direct current (HVDC) to transport electricity long distances with less electricity loss.

so DC is back in business.

Oklahoma cheers for wind power, boos for earthquakes

Clean Line Energy is the company behind the new transmission line and several others in the planning stages. When it announced that GE had joined the Plains & Eastern project on November 1, Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin had this to say:

"We are excited to see GE, the world's premier digital industrial company, working with Clean Line Energy on a transmission line that will harness and export Oklahoma's great wind resource...Our Oklahoma First Energy Plan advocates an all -of-the-above energy strategy, and we are proud to see GE once again involved in an effort that will ensure Oklahoma continues to be a leader in all energy production for decades to come."

Barely a week later, Governor Fallin has had her hands full, dealing with the aftermath of a major 5.0 earthquake that struck on November 6 in the city of Cushing, which happens to be home to one of the largest oil pipeline hubs in the world.

Seismologists have not yet weighed in with a verdict, but given the state's recent earthquake history, early reports are already linking the temblor to the practice of disposing wastewater from oil and gas operations into wells.

In fact, evidence of the linkage is so strong that Governor Fallin accepted it as fact last year and began requesting voluntary mitigation measures from disposal well operators.

That looks like a case of too little, too late. The earthquake has activity continued apace this year, despite a series of additional measures overseen by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission, the agency that regulates disposal wells.

The OCC has not waited around for confirmation for the cause of this latest earthquake. On November 8, the agency announced an action plan covering 58 disposal wells in the region.

Some of the wells were already shut down under previous actions, including one in 2015 and 15 that were shut down in September in response to a 5.3 earthquake near the City of Pawnee.

Of the remaining wells, all located within six miles of the epicenter of the quake have been ordered to cease operations immediately. The remaining wells, located up to 15 miles away, have been ordered to sharply reduce disposal volumes by next week.

The agency has also warned that "that this plan is an initial response, and operators are being warned that work is underway on a broader plan that will encompass a greater area and more Arbuckle disposal wells."

OCC expects to announce the more comprehensive plan in a few weeks, so stay tuned for that.

Image (screenshot): via Clean Line Energy.

Sustainability Reporting Standards: Time to Trade Competition for Collaboration

Even though SASB, GRI, and IIRC, cater to the same market, sustainability information providers, each company's biggest end users are different. Nevertheless some, particularly SASB and GRI, behave as if in competition with each other, which does not help either of them, nor the providers nor the final users. Time would be better invested in cooperation.

Is there competition?

In an analysis of this competitive situation, in her post Trump versus Clinton or SASB versus GRI Elaine Cohen reports that SASB, in the comments sent about the draft GRI standards, suggested that “Perhaps GRI efforts are better place in providing a forum for stakeholders to voice their concerns………rather than codifying standards…….” Looks as if SASB was telling GRI “get out of the way.” I do not think this should be seen as a dismissal by SASB of the notable contribution of the GRI framework to sustainability reporting, but it is indicative that there is a sense of “competition” between both sets of standards (not as nasty and consequential as the competition was between Trump and Clinton).

Sustainability information is still a fuzzy concept, but by using the terms 'standards' SASB and GRI attempt to convey a sharp image. After all, 'standards' are very well defined, with consensus among users. Both SASB and GRI are guilty of sharpening a fuzzy concept. And it all started with the creation of the SASB, partly fueled by perceived weaknesses in the GRI framework. Even the name was meant to recall the true and tried financial standards of the FASB and provide instant credibility by association. By being 'standards,' they would certainly be superior to a 'framework.' GRI must have felt threatened as, shortly after the introduction of it's landmark G4 framework update, it moved speedily to convert the guidelines into sustainability reporting standards. This was achieved by changing some of the language and rearranging the content of the framework to look more like 'standards.' It convened a group of experts under the competitive name of Global Sustainability Standards Board, (GSSB) to guide the process, although this is far from a standard setting institution. Now both institutions have standards. FASB, SASB, GSSB, any others SBs? Let’s hope that the IIRCouncil does not change its name to IRSB, Integrated Reporting Standards Board, to enter the competition.

This had led both SASB and GSSB (GRI) to rush their dissemination campaigns, aided by the legion of consultants that make a living providing training and advice on the use of the standards, with providers and users of sustainability information as interested onlookers. This rivalry has helped the dissemination of their products and stimulated the interest of providers and users, although it has also caused unnecessary confusion as they are different products for different final users.

Sustainability information vs. sustainability reports

Some of this confusion is the result of assuming that sustainability information must be compiled in a sustainability report. The preparation of these reports has been heavily promoted by GRI as it means a growing market for its product. It has contributed to the development of a vast industry of advisors, writers, graphic designers, photographers, specialized printers, etc. which are now strong supporters of the adoption of the GRI standards, of the continuity and indispensability of preparing sustainability reports, and of the updating of the standards so that the market continues to need their training and advisory services (disclosure: the author of this article does provide these services). They have significant intellectual capital invested in the GRI framework/standards that needs to be preserved.

But what stakeholders need is sustainability information, not necessarily complied in a formal, quasi-standardized report. And this is where the difference between SASB and GRI is stark. SASB supports the preparation of information for a very narrow set of users of sustainability information: providers of financial resources. As such their concerns are that the information be of interest to the users and be material, defined as having a direct or indirect impact, preferably tangible, on the financial condition and operational performance of the company. For SASB the relevant sustainability information is that which supports the business case. This information can be presented in many ways, which are not specified by SASB, except to suggest quantitative and qualitative (worded as precise as possible) indicators.

The major issue for SASB is the link and the certainty of the link between the indicator and actual impact on financial performance. They go to some length to show that the action contained in the indicator 'should' have a financial impact. But does it? The key is the transmission mechanism between the action and the impact. If customers do not care or do not know about the working conditions, or financial analysts do not consider the issue in their recommendations, or if investors do not act on the sustainability of the company, the financial impact may not be realized. To justify the inclusion of the indicators SASB seeks to provide 'evidence of impact,' but the evidence tends to be derived from academic studies on the aggregate of many firms and on the efficiency of markets in incorporating sustainability information, not for the particular case of a given company, under its context and its circumstances. For instance, reduction of emissions should reduce risks and affect the cost of capital. But, it this the case for the specific reporting company? Does the transmission mechanism work? The expectation is that the impact will eventually be realized, hence in a long term view, the sustainability action is material.

GRI takes a broader view of stakeholders and includes all of them, and prompts the identification of the issues that affect or are affected by them (very different definition of materiality from SASB). But the criterion for issue inclusion is the interest of stakeholders in knowing the information and potentially acting on it, not necessarily on the potential financial impact as is the criteria of SASB. Even though the GRI standards call for prioritization of material issues, it wants to serve all needs of all users, calling for the preparation of (extensive) sustainability reports that, in general, serve none of them. But by now the sustainability market has come to expect the publication of a sustainability report under GRI framework/standards. To not publish one is considered a lack of respect for stakeholders or even an indication of poor sustainability performance. Actually one of the most used indicators for the progress of sustainability is the number of reports published or the fact the reporting is being extended to SMEs (even though it may not be cost effective for these firms), among others. And it has become a must, as sign of responsibility, of “compliance,” of prestige, to follow GRI framework, now standards.

And what if the value added of the Integrated Reporting framework? It overlays both SASB and GRI standards, supporting and expanding them. It promotes the preparation of reports with an expanded set of financial and non-financial information (that includes sustainability), by proposing to report the contribution of the company in the advancement of the six capitals (Financial, Manufactured, Intellectual, Human, Social and Relationship and Natural Capital), not just the impact on financial capital as in the case of SASB or the scattered reporting, with non-explicit impacts, of GRI. It one could overcome the problems of measurement of impact on the six capitals, it would be the ultimate report on the contribution of the company to society. This shows the direction of financial and non-financial reporting, even if the measure of this contribution is still in its infancy.

Compete or “collaborate to compete”?

Contrasting the approaches to sustainability information of the targeted SASB information to a set of stakeholders with the all-inclusive (in spite of its efforts to focus on material issues) dispersed requirements of GRI, in the wider but focused context of the contribution to the six capitals of the IIRC one could conclude that effectiveness, in the long run, suggests that efforts should be directed at producing and disseminating targeted information to the different stakeholders along the lines of the six capitals, i.e. “six SASBs”, one for each capital. In our previous article Is competition between sustainability reporting standards healthy?, we argued for the availability of sustainability information to fill the needs of stakeholders. With the cooperation and integration of …

“….these standards companies could prepare information, almost like a “universal report” in a comprehensive online information dataset which would allow each stakeholder to pick and choose the information that is material to them and let the software compile the report, including qualitative descriptions and quantitative data or indicators. From all of that WE, the stakeholders, will determine what is material to us in our decision making, which is the materiality that matters.”

And if the information were to include the impact on the capitals, it would significantly enhance its usefulness. So far the indicators and the narrative, even if standardized, leave a lot of the work in the hands of the users. Eventually companies will move to make this impact more explicit.

In the meantime the proliferation of “standards” is not helping to advance the cause of sustainability, distracting the scarce resources within companies and the limited capacity of the users in information processing and understanding its implications. And in the confusion, many institutions are proposing other models for sustainability information, the latest of which is the proposal of BSR in Triangles, Numbers, and Narratives: A Proposal for the Future of Sustainability Reporting.

Antonio Vives is Principal Associate at Cumpetere, a CSR consulting firm. He is also Adjunct Professor at Stanford University and a former member of the Sustainability Advisory Panel at several multinationals. He was the Sustainable Development Manager at the Inter-American Development Bank. Has published seven books, dozens of academic papers and more that 300 blog articles on CSR and financial management (www.cumpetere.blogspot.com ) and is a frequent speaker at conferences and universities. Holds a Ph.D. in Corporate Finance from Carnegie Mellon University. Follow him on twitter @tonyvives.

Child Labor In the Clothing Industry

The clothes you wear may be traced back to child labor. It’s a far more common problem than many of us realize. Children work across the clothing industry supply chain, from cotton fields to mills to garment factories.

There are wide reports of child labor in the cotton sector. Up to 99 percent of the world’s cotton farmers are in developing countries, with nearly two-thirds in India and China, according to a report by World Vision Australia. The children working in these cotton fields “receive little, if any pay,” the organization found. For example, children working on a cottonseed farm in Gujarat, India, receives less than 75 cents a day. They may work up to 12 hours a day in “extreme temperatures.” Reports of child labor in Uzbekistan, India, China and Egypt are also found “on a disturbingly large scale,” according to World Vision.

Child labor in India's cotton sector is particularlly prevalent, Anindit Roy Chowdhury, program manager of the C&A Foundation, told TriplePundit.

A 2015 report, titled Cotton’s Forgotten Children, shines a light on just how widespread child labor is in India’s cotton fields. Almost half a million Indian children, with the majority being girls belonging to Dalit (low caste) and Adivasi (tribal) families, work on cottonseed farms. Children under 14 years old account for almost 25 percent of the total workforce on cottonseed farms in India. In the Indian state of Gujarat, which has the largest cottonseed production in India, children account for almost 55 percent of all children employed in the cotton sector.

Child labor is common in India overall. It is not only in the cotton sector. “It is everywhere,” Chowdhury told us. It is so acceptable that children who work in cotton fields will not complain. “They don't even realize the kind of exploitation they are experiencing,” he said.

A number of factors contribute to child labor in India. One is that it is “socialized and therefore accepted,” Chowdhury explained. Poverty and illiteracy are two other factors, according to UNICEF India. When parents are trapped in dire poverty, their children are more likely to work in the garment sector and cotton fields. Or as UNICEF India put it, “Poverty and a lack of livelihood options lead to a child’s 'need' to contribute to the family income.”

"In the Western context, a lot of people look at child labor and feel awful about it. In our country -- where child labor is common, especially among the poor and marginalized -- we kind of accept it as a given,” Chowdhury said. "So, even people who otherwise condemn child labor, when they see child labor in action, because of the context that these individuals come from, there is an automatic acceptance that this is their reality and this will probably always be there."

Many of the children who work in India’s cotton fields do so on their own families' farms. As Chowdhury explained: “It's not as if these children are coming from elsewhere always. More often than not, these are children whose parents own these cotton fields.” Many small and medium cotton field holders just can't afford to hire labor, so their families work in the fields. And some children migrate from their villages with their parents to work in the fields. They are taken out of school. “Families are most often involved,” he said.

A big reason why child labor is so prevalent in the cotton sector in India and other countries is that there are advantages in using children to pick cotton. “Children are of a particular height. It's easier for them to pluck the cotton because they don't have to bend,” Chowdhury explained. “They are of the same height as the cotton plants. An older person who is far taller would have to bend to actually do the plucking.”

How can child labor in the clothing sector be reduced?

Child labor persists “on such a large scale,” according to the 2015 report on the Indian cotton sector, because of the “limited coverage and insufficient impact of the present interventions.” Some non-governmental organizations such as the C&A Foundation have programs and models to help combat the problem of child labor, but they need to be scaled up.

Chowdhury believes NGOs can “create models, but they have to be implemented and scaled up on a larger level by the government.” And the government needs to “play a proactive role,” he added.

What about companies and consumers? Can they play a role in combating child labor? Companies can improve their supply chains by having policies in place to both prevent and manage child labor.

H&M is a good example. The company states on its website that it takes a “clear stand against all use of child labor and it is a minimum requirement for all factories producing for H&M.” The company continuously monitors compliance with its requirements in the factories that makes the clothes it sells. One thing H&M does to ensure compliance is work with local doctors who help auditors judge how old a worker is if they think he or she looks “particularly young.” The first time H&M finds a child employed by one of its suppliers, it works with the supplier to rectify the problem. The second time it finds a child employed by the same company, H&M stops working with the supplier.

Consumers can also play a role in ending child labor in the clothing industry. “One thing which I believe can have a strong impact is consumers questioning where their clothing comes from,” Chowdhury said.

People need to consider both where and how the clothing they buy was made. If consumers stop buying products from companies that are known to use child labor, then those companies will work to end child labor in their supply chains. Most consumers simply do not realize that their clothing purchases may sponsor child labor, but once they realize, they can use their purchasing power to bring about change.

Image credit: Flickr/International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), India

Agreement Reached on 'No Deforestation' Standards for Palm Oil Companies

After water scarcity, deforestation is arguably one of the most pressing environmental issues of the 21st century. The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has long suggested that as many as 1.6 billion people depend on forests for their livelihoods. And over the years, many environmental groups and publications touted forests as the “world’s lungs” for their role in removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and working as a massive carbon sink.

But due to the growing demand for fuel, beef, timber, paper and commodity crops, the world’s forests -- along with the people who live within or rely on them -- are under constant threat.

After commercial agriculture and cattle, the multinational insurance company Allianz named palm oil as the third largest driver of global deforestation. And demand for this product, which goes into just about everything from snacks to personal care products, only keeps growing -- behooving the industry to take more proactive action. Deforestation resulting from the conversion of land into palm oil plantations has become a huge problem in Indonesia, where land rights are often ignored, wildlife is disappearing and air pollution from the burning down of natural forests for agricultural purposes has become a public health disaster.

More organizations, whether they use palm oil or not, have become cognizant of the the fact that forests are an important pillar of the global economy, and that these lands need to be preserved and managed correctly if the world will support 9 billion people by 2050.

How to act in order to stall and even stop deforestation, however, poses many difficult challenges. To that end, a coalition of businesses and nonprofits agreed to a set of standards in Bangkok this week that it insists can make global deforestation commitments more seamless to develop, implement and enforce.

The result is a new set of standards that merge two different deforestation guidelines. A working group, which has been in discussions for a year, took principles from both the High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) and High Carbon Stock (HCS+) methodologies. One must really get into the weeds (or the trees) of both standards to really measure the differences between these zero-deforestation guidelines. Nevertheless, a more streamlined set of guidelines should eliminate confusion over deforestation policies within companies – while forcing them to become more transparent about their supply chains and operations.

The result is an agreement that stakeholders say will offer the palm oil industry more clarity on how it can implement no-deforestation claims about their operations. Fundamentally, there are three areas of focus by which companies will be measured as they publicly disclose their no-deforestation commitments.

Social requirements: One of the largest problems palm oil production causes is displacing people off their lands. Many of these citizens lived in their communities for generations, but had no official title to their land. The principles of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), which give indigenous people the right to grant or not grant access to lands on which they live, took greater root in recent years. Guidance on how to mitigate impact on people and their lands will assumedly include FPIC; the final standards are expected to be completed by the end of 2017.

Young regenerating forest (YRF): One reason why the High Carbon Stock guidelines have become more accepted by NGOs and companies is that they use copious amounts of data to suggest what types of forest areas should be preserved, versus what lands are better primed for development. One key classification of land is “young regenerating forest” (YRF). These recently cleared forests have gained much regrowth and still house patches old-growth forests. They are a grey area: They fall within the “no deforestation” zone, but could also be important to local economic development. These new standards protect larger swathes of land with old-growth forests, but also give local communities say in how these YRF lands are maintained.

Carbon: This working group has called for a more sophisticated system on how to measure carbon stock data, which in turn can have an impact on decisions related to forest development or preservation. In addition, soil quality will have even greater emphasis; the accounting of carbon within peatlands will become even more important (as these ecosystems are a huge carbon sink); and measurement tools more aligned with those of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) will become the standard as companies will soon become required to be even more transparent when they disclose their carbon footprints.

In recent years, more companies have made bolder commitments to stamp out deforestation within their palm oil supply chains. But WFF and other NGOs express concern that these policies are ambiguous and are difficult to verify. A clearer set of guidelines on how to implement no-deforestation policies will not only benefit local communities and forests, but also companies, as more transparency will result in more trust from consumers and stakeholders.

Image credit: Glenn Hurowitz/Flickr

Climate Change: Americans Are Getting Pushed Out of Their Homes

The thing about climate change is that not only is it a global crisis, but there’s also a crisis within the crisis: People choose to ignore it. However, when the effects of climate change become visually noticeable, people start to do something. Climate change has affected thousands of Americans, and it’s time they stop turning their heads.

How would you feel if you were forced to move because your house was destroyed? Global warming has been the root of natural disasters that leave many Americans devastated and, sadly, homeless as well. As glaciers melt and sea levels rise, the people of America have no other choice but to move inland, away from a place they once knew as home.

Global warming disasters

Although some scientists don’t think global warming is the root cause of natural disasters – because they’re just that, natural – it is most certainly affecting their strength and frequency. As temperatures continue to rise around the globe, weather-related natural disasters are likely to occur, scientists say. Due to the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the Earth gets warmer – and more intense storms are no surprise. As greenhouse gases are continuously emitted into the atmosphere, things are only going to get worse.It’s predicted that tropical storms will increase in intensity, because of the amount of water vapor going into the atmosphere. It’s like throwing gas into a fire. Not only will this affect tropical storms, but hurricanes will also significantly increase in intensity. Hurricanes, coastal flooding and tropical storms are what’s forcing Americans out of their homes. Climate change is only making it worse.

Individuals need to get on board

The Golden Hammer Award is given to someone who exemplifies the mission of Habitat for Humanity and does something for the greater good. Robert K. Mericle is a recipient of this award for building a home for a family who needed it, but could not afford it. If more people chose to stand up to climate change like Mericle did, there would be many more homes for people who lost or will lose theirs to natural disasters.This is a great response to climate change and shows Americans helping their fellow Americans. The only way people will survive the devastation of climate change is by banding together. In order to combat climate change, both the people and the government need to get on board.

Entire towns are affected

Shishmaref is a coastal Alaska town with about 650 residents. Due to rising sea levels, this entire town is on the verge of moving. The move would cost about $180 million and leave the village lifeless as it awaits its extinction, destined to eventually be covered by water.More towns face threats like those faced in Shishmaref, and such threats will grow over the next decade. A house is a home, and so are the towns in which the homes reside. Americans are being told to move to avoid natural disasters. When natural disasters strike, thousands end up homeless. There’s simply not enough government funding to re-home everyone who loses theirs. As more unsafe areas arise throughout the country, more Americans will have no other option but to leave their homes.

Climate change is a treacherous battle the entire world is facing. It’s time American comes together and combats this crisis.

Image credit: Pixabay

3 Things the Social Justice Sector Can Do to Make History

The 2016 Net Impact conference convened in Philadelphia last week with a bold call-to-action: Make history. And at a time when global challenges like climate change, resource scarcity and social inequity make our future uncertain, the demand for leaders with the courage to make history has never been greater.

When it comes to social justice, consider a few statistics raised by Michael Smith of My Brother’s Keeper:

- Black, American Indian and Hispanic children are between six and nine times more likely than white children to live in areas of concentrated poverty.

- 80 percent of children of color are not reading at grade level.

- Black boys make up 6 percent of the American population, but are nearly half of the nation's murder victims.

- A black baby boy born 25 years ago has only a 1 in 2 chance of being employed today, due not only to socioeconomic factors, but also to early death and over-incarceration.

- Nearly half of black men are arrested at least once for non-traffic-related crimes by age 23.

Those stats are pretty grim, but this one isn't: If we closed the gap in labor force participation between 16-to-54 year-old men of color compared to white men, total U.S. GDP would increase by 2 percent.

That finding came from research at Smith's own My Brother's Keeper, President Barack Obama's initiative to address persistent opportunity gaps faced by boys and young men of color. President Obama formed the initiative in the wake of the verdict in the Trayvon Martin case, when he famously said: "Thirty years ago, Trayvon Martin could have been me."

Smith elaborated on Obama's motivations behind the program: "When you hear the president talk about this, he will say we have a moral obligation to make sure that America remains a place where you can make it if you try. But he would also say we have an economic imperative because America cannot remain globally competitive when we are satisfied with writing off so many young men who are sitting on the sidelines."

Smith, who lost his younger brother to gun violence, serves as special assistant to the president and senior director of cabinet affairs for My Brother's Keeper. He said his and his brother's story proves America has a long way to go before we can close the opportunity gap for children of color. But he insisted today's somewhat contentious landscape provides an open avenue for social change-makers.

As he wrapped up the Net Impact conference on Saturday, he shared three things the social justice sector can do to make history.

1. Be fearless

While Smith was a senior vice president for the Case Foundation, his team put out a campaign called Be Fearless. Smith said the family foundation intended to spark a conversation about how to take more risk and be be bold in the social sector. "Because if we can’t, then who will?," he asked rhetorically. "Why is it okay for an athlete, an entertainer, an entrepreneur to be fearless, and we’re incremental and slow?"

The Case Foundation commissioned research on the common attributes in fearless change-makers. Two in particular stood out to Smith:

- They make big bets: "People don’t want to follow the incremental," Smith said. "They don’t want 500 different things. They want a big call to action like: ‘We’re going to end malaria. We’re going to have a play place in walking distance to every kid. We’re going to make sure every young man of color in these 10 communities has a job.' Make a big bet for your work."

- They constantly experiment: "They figure out how to do R&D even when they don’t have R&D money. They make failure matter. They don’t get lost and sad about failures. They learn from them, and they build on top of them," Smith said. "Don't get stuck."

2. Be collaborative

"If you want to make changes, it’s no longer just the private sector, the social sector, philanthropy or corporations," Smith said. "It’s all happening together"

In 2007, the State Department launched the U.S.-Palestinian Partnership to create educational and economic opportunities for Palestinian youth. The Case Foundation was one of many partners on board. And Smith said the initiative proves what's possible with collaboration.

"We worked with the Bush administration; we worked with the Palestinian government," he said. "Because if you want to partner in peace, you have to make sure people have open opportunity."

The partnership included a venture capital fund, youth development centers powered by Boys and Girls Clubs of America, and developer days with Google staff. "You’ve got to figure out how to play to the strengths of each of the sectors coming together if you want breakthrough innovations," Smith advised. "If you want to go far, go together."

3. Bet on the winners

"We spend $300 billion a year in America on nonprofits, where 80 percent of them don’t do any sort of research. More than 50 percent don’t have a theory of change or logic model," Smith explained. "So, the pie is not getting bigger. Since the recession, the revenue that’s going to nonprofits is flat or a little above at best."

So, what's the solution? "One, we have to bet on the winners. And two, we have to come up with some creative strategies for social financing."

Bet on the winners sounds a bit like a line from "The Wolf of Wall Street," so how does it apply to the social sector? How can donors and partners pick winners and losers when it comes to nonprofits? Smith said the first step is a major overhaul in the way nonprofits measure success.

"Make sure we’re judging outcomes, not outputs," he advised. "Don’t ask me how many kids went through the program. Tell me how many kids went to college, stayed in college, went on and got a job."

Smith pointed to Pay for Success, which launched under his direction at the the Social Innovation Fund. The initiative provided a new contracting and financing model that leverages philanthropic and private dollars to fund services up front, the result of multiple feasibility studies and research projects. In the model, the government, or another entity, pays after the services generate results.

It sounds simple, but it's something of a breakthrough. And the strategy gained strong bipartisan support for increasing return on taxpayer dollars while improving the quality of services.

"We get really okay in the nonprofit sector patting ourselves on the back with one good story," Smith said. "But if we’re going to have breakthroughs, we’re going to have to focus on outcomes and we’re going to have to bring new dollars in the space."

The bottom line

In closing, Smith pointed to a famous Greek proverb: "A society grows great when old men plant trees in whose shade they know they shall never sit."

It seemed fitting for a crowd of mostly post-graduate students. And it resonates all the more as we reach a turning point in the fight for social justice and equity in America. Smith shared a particularly evocative story of what the quote means to him:

"I was sitting at the opening of the African American History Museum a few weeks ago. I looked at John Lewis, and I looked at the great civil rights leaders. It made me think that so many of us are sitting under the shade and benefiting from the fruit of the trees they planted a generation ago. We’re sitting there, and we’ve got no shovel. We are not planning to plant the trees for the next generation."

He challenged the crowd of self-proclaimed change-makers to think about how they could pick up the shovel. It's not unlike John F. Kennedy's remarks in his 1961 inaugural address, "Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country."

So, how will you raise your shovel? What will you do for our country, for society and for the planet? As students, business professionals and nonprofit leaders, it's up to each of us to decide. But the fact that we're raising the question should give us hope for the future.

"That’s what this is all about," Smith said. "We’re going to act with urgency. And we’ve got to realize that we need to get some shovels ready."

Image credit: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza, courtesy of My Brother's Keeper