Ford F-150s Now Upholstered With Recycled Plastic Bottles

Heaps of plastic waste are generated daily in the United States—32 million tons in 2012, according to the EPA. Less than 10 percent of plastic garbage ends up recycled as most of it is entombed forever in municipal landfills. Ford has taken a tiny step towards waste diversion by incorporating more materials made from recycled plastic in its vehicles. Yesterday the automaker announced fabric made out of recycled bottles will be used in its F-150 line of trucks.

According to Ford the company is the only automobile manufacturer to use REPREVE, a fabric manufactured by Unifi, in some of its vehicles. The company claims the use of this product will prevent approximately 5 million plastic bottles from ending up in landfills.

Ford’s relationship with Unifi ramped up a few years ago when the automaker selected the nylon manufacturer as its upholstery supplier for the Focus Electric model. At the time Ford touted its partnership for using an average of 22 plastic bottles in each car, for a total of 2 million bottles diverted from landfills. The company has also experimented with alternatives to fossil-fuel based plastics in its vehicles, though most new materials have only made token appearances in vehicles. In fairness to the company, materials such as soy or coconut fibers are difficult to scale and do not match conventional materials in overall strength and performance.

So in the grand scheme of things, will Ford’s use of plastic bottles make much of a difference on the environmental front? Of course not: 5 million bottles may ring loudly as an impressive number, but it is only the equivalent of the amount of plastic bottles Americans throw away in 12 to 13 minutes. And let’s look at the overall carbon footprint of the F-150, starting with its mileage: at 19 MPG on city streets and 26 MPG on the highway, it is an improvement over older models of trucks, but it is still relatively high compared to other vehicles on the market. And considering the demographic interested in the F-150, recycled fabric is not going to be the truck’s larger selling point anyway.

While automakers, especially Ford and GM, are trying to outdo each other at almost a silly pace with how they are becoming more sustainable, you have to give them credit when it comes to recycling. Cars and trucks (if you can past their overall lifetime carbon footprint) are one of the most recyclable products on the market: 75 to 90 percent of the content of that vehicle ending up in the local junkyard can be recycled. In the case of a mothballed F-150, that number could edge up a bit. Unifi has a program that incorporates old fabric into its recycling stream, so hopefully Ford will find a way to close that loop a little tighter down the road.

Based in Fresno, California, Leon Kaye is a business writer and strategic communications specialist. He has also been featured in The Guardian, Clean Technica, Sustainable Brands, Earth911, Inhabitat, Architect Magazine and Wired.com. When he has time, he shares his thoughts on his own site, GreenGoPost.com. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Image credit: Ford Motor Co.

Overcoming Gender Inequality in the Tech Sector

We all know gender inequality in tech is a tough nut to crack. Women throughout the economy face persistent wage inequality. Seventy-six percent of STEM jobs are held by men. Among those women who do make their way into the STEM workforce, as many as 50 percent are expected to eventually leave because of unwelcoming work environments, limited promotion opportunities or a lack of sponsors.

But that doesn’t mean good people aren’t trying to solve the problem. Yesterday, in partnership with Symantec, we brought together a number of smart women and men for a roundtable discussion on gender inequality in tech. In attendance were Code 2040 and Girls Who Code, two non-profits that are trying to address one root of the problem -- girls leaving STEM education as early as middle school. We also had representatives of companies including Facebook, Edelman and of course Symantec. These organizations and others are actively looking to improve their diversity record and foster a culture of diversity. Finally we had organizations that are committed to diversity from the core: the Clayman Institute for Gender Research, Net Impact, Global Fund for Women, and the National Center for Women and Information Technology.

This mix of bright women and men chattered away discussing not just the problem but micro and macro solutions that could be embedded in any organization. Here are some of our key takeaways.

The pipeline

Code2040 and Girls Who Code are both actively working to increase diversity in the workplace by encouraging young people to study STEM. But the pipeline doesn’t just provide a pack of worthy applicants for Silicon Valley’s entry level positions in software engineering. The pipeline also move individuals along the corporate ladder. If that percentage of women participants is low to start with, it’s even lower at the top ranks. Symantec has an unusually high percentage of women on its board at 30 percent. To put that in perspective, Twitter’s board was 100 percent male when the micro-blogging platform IPOed. Now, one of its eight board members is female, making the board 12.5 percent female. Not to kick Twitter while they’re down, but the board actually has has 3 times as many board members named Peter as it does women.

Our roundtable participants didn’t dwell on sad statistics, though. They were quick to provide practical solutions for moving women along the pipeline. The key, the group concluded, is a mix of mentorship and sponsorship. Mentorship comes from employee resource groups, based for example on gender, race or sexuality. These groups give employees a safe space to air their feelings with their peers. According to Kunbi Adeyemo of Facebook, these are one of the most effective tools for improving retention rates among minority staff members. But a place to kvech isn’t enough. Entry and mid-level employees also need sponsorship from executives to help ensure they gain the skills required to move up in the organization. Amy Lazarus of Inclusion Ventures called the two tools “bonding capital and bridging capital.” The bonding capital gets you friends and supporters while the bridging capital gets you to the next level of the organization.

On tokenism

Check out the websites and press materials created by most companies and they appear to be much more diverse than they actually are. While these photo shots and speaking opportunities can raise an employee’s profile, they can also put a burden on them, especially if the same few people are tapped again and again. Antoine Andrews, director of global diversity and inclusion at Symantec joked, “I see the same woman representing a company again and again at different conferences. It makes me wonder, is she the only woman they have?” Adeyemo pointed out that these opportunities can also have a negative impact on professional development. “Each of those opportunities means less time to code.”

Overcoming bias

Bias in the workplace can lead to death by a thousand cuts for women and people of color who are trying to move ahead. Everything from a lack of sponsorship to a quiet voice can hold qualified candidates back. But there are many tools available for helping companies overcome bias. Implicit bias training can give employees a shared language for talking about bias at work. Karla Monterroso of Code2040 uses math allegories to help explain how corporate resources can make it safe for minority employees to speak out against bias. This tactic can help depersonalize a potentially emotional issue while offering organizations “practical, tangible, specific goals at department level.” At Facebook, Adeyemo’s team uses real examples of bias that have been reported to HR to bring home the point that these things are happening here and now. Real stories go a long way toward making employees understand why bias training is important and how it can benefit their relationships with co-workers.

All the participants agreed that tech’s “myth of meritocracy” was important to challenge during bias training. While intelligence and skill go a long way toward being successful in STEM work, “cultural fit,” helps applicants seal the deal. “Culture fit” is a potential minefield best avoided by hiring managers -- it can easily mean “has an accent I don’t understand” or “difficult to make small talk with,” signifiers of diversity that don’t have much to do with someone’s ability to do the job.

Measure what matters

These concepts are all well and good, but they can be awfully difficult to track. Our panelists had some great suggestions for improving tracking around diversity. Since the tech sector is quite handy with aggregated data, metrics can be a good method for building the case for diversity -- if you use them right. Monterroso shared a tool she uses at Code 2040 -- net promoter score. We're all familiar with being asked "On a scale of 1-10, how likely are you to recommend this product to your friends?" By using these questionnaires to track employee satisfaction, and then separating the respondents by gender (or race or whatever metrics you're looking to track), trouble spots can come to light that might otherwise not be visible. This approach also protects the person giving the score because the individual does not have to speak out directly.

At the end of the day, no one can fix gender inequality, but we can all do our part -- by being a little bit mindful and a little bit sensitive to the fact that those around us might have a different set of experiences.

Puerto Lopez Ecuador: An Ecotourism Destination that Falls a Bit Short

My ecotourism adventure in Ecuador continues in the small fishing village of Puerto Lopez on the Pacific coast. Machalilla National Park -- with its beaches, dry and fog forests, and islands -- is located nearby, creating more ecotourism activities. Sport fishing, scuba diving, snorkeling and visits to nearby islands all showcase the stunning natural beauty of the area. Humpback whales frequent the coast during the summer months, attracting tourists in droves.

Early morning activity in Puerto Lopez begins with the fisherman returning to shore with their catch and the fish market that ensues. Fish are crated, weighed, sold and grilled as the sun rises and frigatebirds cruise around. A handful of village businesses are also impressive from a sustainability standpoint.

A couple beachfront hotels cater to the more eco-minded tourist, included the Ecuadorian owned Punta Piedrero Ecolodge and Camping (where we stayed), and the European-owned Hosteria Mandala. The former helped close down an illegal sea cucumber operation, which exported this Chinese delicacy and had unlawfully built a plant on the property before the Ecolodge was constructed. The latter hotel partnered with other organizations to move a whale skeleton from a nearby beach and make it into an educational display.

Another noteworthy business venture is the palo santo industry, which makes products commonly used in folk medicine from the heartwood of the tree. El Artesanal has a small manufacturing facility on the outskirts of Puerto Lopez where they product palo santo oil, incense and scented soaps. The company also has a sustainability mission. The products must be made from the wood of dead trees, so the company doesn't contribute to deforestation and cuts no live trees. El Artesanal also has a nursery for saplings and helps with reforestation efforts near Puerto Lopez.

Pacha Chocolate Boutique is run by a French-Ecuadorian couple who gives chocolate tours and uses regionally-harvested cacao to make bars, nibs and brownies. It is a great opportunity for people from colder climates to learn about the chocolate-making process, including a visit to a cacao farm.

Some tourists with looser itineraries volunteer at Clara Luna, a nonprofit organization that offers education-based programs in the local community. Many foreigners are tutored in Spanish and volunteer for the after-school programs for children, which offer English language instruction and other activities. My young daughter served as an 'assistant' for several of their classes.

There is also an indigenous community in Agua Blanca within Machalilla National Park that sustains itself largely from the $5 per person that is collected to visit. A guide leads visitors through a museum, ruins, a mud treatment and a therapeutic sulfur lagoon.

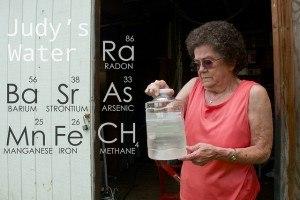

With all the ecotourism activities in Puerto Lopez, what's not to love? Two sticky issues stand out. The first is the lack of infrastructure to support the growing tourist population, and even the locals. Although the government recently invested in a multi-million dollar dock, there is no state-run water treatment facility in the area, and waste is pumped from the houses into trucks and taken off-site for 'treatment.' There are also insufficient water resources, requiring water to be trucked in for much of the year from rivers. Hotels pay $40 for a large truckload of water and $80 to treat their waste.

You'll also notice a lot of litter around town, most notably on the beaches and in the local stream. On my stroll along the beach today, I saw pieces of coral wrapped in plastic debris. And stray plastic bags greeted us during our afternoon swim. A walk through the fish market reveals some seemingly illegal activity, as a hammerhead shark and other protected species are carted off, but poverty and access to global markets can motivate the breaking of laws.

A restoration effort seems to be underway on the local stream, where mangrove trees were planted and a nice walkway with bridges was constructed. This project, however, is plagued by litter -- with discarded fishing nets, bottles and tires clogging the area.

Although I love watching my two young children engage in creative play on the beach, it is sad watching them make 'birthday cakes' out of discarded styrofoam bowls, with a plastic soup spoon serving as the candle.

Image Credit: Le Minh Vu

Sarah Lozanova is a regular contributor to environmental and energy publications and websites, including Mother Earth Living, Green Builder, Home Power, and Urban Farm. Her experience includes work with small-scale solar energy installations and utility-scale wind farms. She earned an MBA in sustainable management from the Presidio Graduate School and she resides in Belfast Cohousing & Ecovillage in Midcoast Maine with her husband and two children.

Mushrooms to the Rescue in the Ecuadorian Amazon

I’m not sure if you’d have any luck selling Hollywood on the idea of a superhero that happens to be a mushroom, but the idea would, at least, have a factual basis.

We should be grateful for mushrooms. Not just because they are delicious on pizza and in stir-frys, but because they also go around behind us, quietly cleaning up our messes, a little bit like Mom does.

Mom, as in Mother Earth, it would seem. The Sucumbíos province of northeast Ecuador is home to nearly a thousand toxic waste pits. And it is here that a group called the Amazon Defense Coalition has recruited specialized fungi with an appetite for toxic waste.

These open toxic pits are the legacy of Texaco’s adventure in the Amazon, subject of the documentary film "Crude." Over a billion gallons of untreated toxic waste were dumped in this nearly pristine rainforest, creating a cancer zone the size of Rhode Island. The spill is the subject of a multi-billion dollar lawsuit filed on behalf of 30,000 inhabitants of the region, whose lives have been devastated by the pollution of land, water and air. Chevron, having taken over Texaco, is responsible, but the company refuses to pay. It has successfully dragged out the action for 22 years, claiming that it will fight “until hell freezes over.”

This is where the U.S.-based non-profit Amazon Mycorenewal Project has joined forces with the Instituto Superior Tecnológico Crecermas (ISTEC), the only higher education institute in the region, to form the Alliance of Bioremediation and Sustainability in Sucumbíos (ABSS).

The organization's plan is clean up the one of the world's largest oil disasters — using giant, petrophilic (oil-loving) fungi. At the same time, ABSS hopes to transform this devastated region into a mushroom competency center, with ties to local indigenous communities -- where this very specialized knowledge, and more, can be exported throughout the world. In this way, the organization “seeks to incubate sustainable community development projects as a method to alleviate poverty and raise the standard of living in the Sucumbíos region.”

When it comes to mankind’s toxic mistakes, of which there are many, mushrooms might just be the superheroes we need. There are over a million known species of fungi, so we are just starting to scratch the surface of what they can do. But not only can fungi (including oyster mushrooms) produce enzymes that can break down the long chain hydrocarbons found in petroleum, but they can also eat polyurethane plastic, absorb heavy metals like mercury and even clean up radioactive spills.

Check out mycologist Paul Stamets’ TED talk about six ways that mushrooms can save the world. Besides cleaning up polluted soils, he also describes making insecticides, treating smallpox and even flu viruses with fungi.

In an earlier post, I wrote about ongoing efforts that can turn plastic waste into food. We should be very grateful that these amazing organisms exist. They just might be able and willing to bail us out of some of our worst self-inflicted disasters. Let’s just hope that when the going gets rough, the mushroom species we need most is not the one that just went extinct as we destroyed its entire natural habitat. It’s another reasons to think twice about our imperialistic conquest of the natural world.

Image credit: Richard Ruppenthal: Flickr Creative Commons

RP recently returned from Abu Dhabi where he attended the World Future Energy Summit as the winner of the Abu Dhabi blogging competition, and he also really likes mushrooms a lot.

Follow RP Siegel on Twitter.

Fracking Opponents Get Creative in Their Tactics

Efforts to stop the march of fracking rigs have gained the most traction at the local level. Voters and legislators have passed more than 400 local bans on fracking -- about half of these in New York -- and many more are in process.

Why is this? Well, as David Spence points out in a survey of local bans in the Texas Law Review, it’s a difference in where the costs and benefits of fracking land. Most of the costs of fracking are borne locally, by neighbors, in the form of air pollution, truck traffic and dried-up creeks.

The benefits, if any, accrue to offsite actors: the handful of companies making millions, and more politically important: state governments that collect the vast majority of taxes and fees.

But this really shouldn’t be all that complicated. Local responses to fracking should really fall under the bread-and-butter tool of municipalities everywhere: zoning.

Zoning codes! They are magical things. They determine the width of sidewalks, the size of pools, the makeup of asphalt. You have to get variances from them to change your roof, build a shed in your backyard or (in some places) build a non-regulation birdhouse. They cover almost everything, it seems, except for six-story, quaking, smoking fracking rigs. The normal process of neighbors arguing over shade trees has been massively disrupted by the lightning-quick appearance of fracking rigs, like so many alien invaders.

The local approach to fracking

In Colorado, the state’s power to regulate fossil fuels assumes that oil deposits are mobile and that they can be tapped from different places, regardless of drilling location. The “field” as a whole has to be managed. At least that’s been the assumption.

As Spence pointed out during his talk at the University of Colorado, Boulder this month, shale deposits just don’t work that way. They don’t move. You have to be at a site to frack it (although now horizontal drills can reportedly go almost 2 miles underground). Fracking is no longer a “field” – it is a local activity.

“No one has yet made the argument that this is a different kind of drilling,” said Spence, whose UT law article covered local ban efforts in Texas, Pennsylvania, New York, Colorado, Louisiana, California, Michigan and other states. “I don’t know why.”

Basically, the law around local control of fracking is so new that the challenges depend mostly on the judge (at least in Colorado). Pennsylvanians have had better luck because rights to “clean air, pure water and the preservation of environmental values” are in the state’s constitution. In Colorado, the state is actively charged with promoting oil and gas development, a statute written before anyone had an inkling of the toll of climate change.

Colorado communities share ideas

Cities and towns are mostly fending for themselves. At a recent conference in Denver called “Local Responses to Fracking: Tools You Can Use,” municipal officials came together to brainstorm and share ideas.

Some towns appointed their own local oil and gas inspectors, regardless of the fact that they had no regulatory power. Some towns instituted MOUs with individual companies as they came to town -- going over emergency preparedness, traffic and more. Boulder County implemented a $37,000 impact fee for road repair.

Some cities looked at conservation easements. Some towns limited or cut off infrastructure, restricting water use, or deciding when and where to build roads. In Pitkin County, Colorado, officials purchased the water rights to land they wanted to preserve. The strategy in Garfield County, which has more than 10,000 wells built since the 1970s, actively partners with the state and gives local communities a toll-free number to call with concerns.

Fracking will evolve, as with any new technology, and the nature of it depends on community engagement. But unless the industry magically decides to change its practices, you’re going to hear a Coloradan’s words echoed by homeowners in more and more counties around the U.S.: “When else can you just put a factory with no walls in someone’s backyard?”

Photo courtesy of J.B.Pribanic

LED Lights Installed in Over 3,000 Habitat for Humanity Homes

Partnering with Habitat for Humanity to install LED lighting in affordable housing units across the U.S., leading LED manufacturer Cree announced it's now offering the new Cree LED Bulb to Habitat for Humanity affiliates.

The company's March 17 announcement expands on Cree's 2010 commitment to provide Habitat for Humanity $1.5 million dollars' worth of Cree LED downlights. “As part of our mission to drive 100 percent adoption of energy-efficient LED lighting, Cree’s goal has always been to deliver LED solutions that save energy and fundamentally improve the overall lighting environment,” Cree Chief Marketing Officer Betty Noonan commented.

“The addition of the Cree LED Bulb portfolio to our collaboration further supports Habitat’s efforts to create affordable, sustainable homes, while enabling homeowners to greatly reduce their energy usage for decades without sacrificing the light quality.”

LED lighting: Big savings, lots of benefits

Residential and commercial buildings account for nearly 41 percent of U.S. energy consumption and 40 percent of national carbon dioxide emissions, according to the Department of Energy's 2011 Buildings Energy Data Book. A cost comparison by EarthEasy estimates that, by replacing incandescent bulbs with LED lighting, end-users can cut their electricity bills by 75 percent over 50,000 hours of use. The total cost of purchasing 25 LED lights is 25 percent that of purchasing 25 incandescent bulbs.

Energy Star-qualified Cree CR6 LED downlights have been installed in more than 3,000 new Habitat for Humanity homes since 2010, Cree highlighted in its news release. Designed to last for 50,000 hours (~5.7 years), Cree's CR6 downlights on average consume 85 percent less energy than incandescent downlights.

“We are grateful to partner with companies like Cree that are helping Habitat serve families in need of affordable housing through product donations that can lower homeowners’ daily living expenses,” Habitat for Humanity International CEO Jonathan Reckford said of the organization's evolving relationship with Cree. “Extending Cree’s current commitment to include the Cree LED Bulb furthers our efforts to build sustainable communities across the country.”

*Image, video credits: 1) Cree; 2) Burgess Lighting; 3) Habitat for Humanity

A Call for Renewables From the Fossil-Fuel Center of the World

Editor's Note: This post originally appeared on the IEEFA blog.

By Tim Buckley

In a must-read report released this week on fast-changing energy markets, the National Bank of Abu Dhabi signals a once-in-a-lifetime opening for investors in Middle Eastern renewables and energy efficiency.

The report, “Financing the Future of Energy: The Opportunity for the Gulf’s Financial Services Sector,” carries the imprimatur of researchers at the University of Cambridge and PwC. Australian readers will be familiar with the author of its forward: none other than Alex Thursby, CEO of the National Bank of Abu Dhabi, and previously the very successful chief executive of international & institutional banking at ANZ (Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd).

What really jumps out, though, is where the report comes from, namely the epicenter of the fossil-fuel world. And while it focuses on investment opportunities in the political and economic union made up of the Gulf Cooperation Council — Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — its conclusions can be carried over in many ways to other parts of the world. Asia and Africa are mentioned in particular.

Here are the “four pillars” of awareness the paper presents:

- “There is a pressing need for investment/finance of both energy generation and energy efficiency improvements over the next 10-15 years, both to secure the needed energy and significantly improve its sustainability … It opens finance opportunities on the scale of tens of billions of U.S. dollars per year in the region and hundreds of billions (to a trillion) U.S. dollars per year globally.”

- “We do not need to wait for the required technologies to appear. Low carbon, sustainable technologies are already on the market, with costs that are dropping rapidly as the industry matures and grows. They are already market-tested and cost effective, especially for solar PV and on-shore wind. This situation is robust against changes in the price of oil.”

- “The West-East Corridor (Africa through the Middle East to Asia) offers a significant opportunity to extend the GCC region’s finance expertise onto the global stage. This corridor will require very large increases in energy generation as well as innovations in energy efficiency so that energy can be used wisely in these fast growing economies. The current lack of infrastructure, as well as the ability of low carbon solutions to attract supplemental finance through the Clean Development Mechanism and related international programs, means there will be continued growth in renewables, which already represent more than half of the global investment in new energy generation over the past several years.”

- “Government policies both in the GCC region and along the West-East Corridor are not yet optimal to unlock this potential finance. Working together with governments, the finance community can play a crucial role in defining the next generation of policies to deliver on the ambitious economic, energy and sustainability visions of the region.”

The report is targeted at banks and investors in the region, although its authors note wryly “it will also be of interest to the energy sector and government partners more widely.”

Indeed.

One of the takeaways is that institutional investors and banks must be proactive about this opportunity and must nudge governments toward “greater stability and support for sustainability ambitions and policies,” a trend that would summon a stampede of investors (“the finance sector will be there to back projects that are consistent with that support”).

The report also illustrates a basic truth about energy development and profitability: value creation is achieved at the nexus of public and private interests. Successful deployment of renewables and development of energy efficiency is more about setting a proactive policy framework that adds balance to an old system that has promoted fossil-fuel development to the detriment of innovation in other energy sectors.

The document offers detail on how Germany has already proven the national viability of renewables, how popular sentiment against fossil fuels is gaining momentum in China’s huge cities, and how solar- and wind-energy development, are now on parity cost-wise with carbon-based energy. It even suggests practical tips on investing, including notes on how “green sukuks” would work (sukuks are Shar’iah-compliant bonds).

The report is loaded with numbers, of course, but perhaps the two most notable ones are these:

- 39 percent, as in the expected increase globally in renewable-energy investment once 2013-2018 totals are compiled.

- $1 trillion, as in the amount of renewable-energy financing required in the region, an enormous sum, to be sure, but not as big as the global demand.

Tim Buckley is IEEFA’s director of energy finance studies, Australasia.

Climate Change Puts California Economy at Risk of Collapse

California faces one more year of water supply. The state is in the grip of a record drought tied to climate change. This water crisis holds the potential to collapse California’s economy if the state truly runs out of water. What an irony that the state most focused on global warming may be its first catastrophic economic collapse victim.

California anchors U.S. economy

This is not an article about California. It is about you, in whatever state you live. California's economy is so large and impacts so many other businesses that its potential collapse due to a water crisis will impact the pocketbooks of most Americans.

California has a $2.2 trillion annual economy. That makes California the seventh largest economy in the world. For all the greatness of Texas, the California economy is approximately twice the size.

California’s companies are the world’s technology leaders. Google, Apple, Facebook, Twitter, Cisco, Disney, Hewlett Packard, Tesla and Solar City all have their corporate headquarters in California. Little know Atomic General located in San Diego is a world leader in military drones. San Francisco and San Diego rank No. 1 and No. 3 among the top 10 biopharma clusters in the U.S.

California is also a global breadbasket: It is the world’s fifth largest supplier of food. The California agriculture industry is highly efficient, and the state is the largest food producer in the U.S., with only four percent of U.S. farms. California’s crop diversity is world class, with the state growing over 450 different crops. Crops exclusively grown by California in the U.S. include almonds, artichokes, dates, olives, raisins, pistachios and clover. The state also produces more than 86 percent of all lemons and 94 percent of all processed tomatoes in the U.S. You might want to drink to California’s agricultural success by having a glass of California wine, as the state is the world’s fourth largest wine producer.

Whether you are a Democrat or Republican, the state anchors your government spending plan as California is the largest federal tax payer among U.S. states. The state also pays more in federal taxes than it receives in federal spending.

Climate change driving California’s drought

Research by Stanford University points to climate change as a key driver in California’s historic drought level. It is not a question of whether California has ever before had droughts. The question of this research was how climate change impacts the severity of weather events like droughts. The findings were that “... extreme atmospheric high pressure in this region – which is strongly linked to unusually low precipitation in California – is much more likely to occur today than prior to the human emission of greenhouse gases that began during the Industrial Revolution in the 1800s.”This research can be yet another climate change deniers’ example of science getting in the way of their personal beliefs or economic incentives, except this time the consequences of denial will impact Americans who eat tomato-based products, use a lemon or search Google.

No water, no economy

Imagine the ramifications for your state if it were to run out of water. That is the immediate challenge facing California. January 2015 was the driest in California since record-keeping began in 1895. This is not a recent weather event: NASA data shows that California’s water storage capacity -- in the form of its lakes, snow levels, water table etc. -- has been in decline since 2002. There is no contingency plan for this level of climate change for the world’s seventh largest economy.

The economic ramification will range from measurable to catastrophic. Two-thirds of the state’s water losses are tied to the agricultural community's pumping the aquifer dry. A point of diminishing return is being reached with increased reports of dry wells. California’s agricultural industry is on the precipice of economic decline and may be heading toward collapse due to a lack of water.

Rationing is now a topic of discussion in California. Water conservation has been as much of California’s culture as energy conservation and renewable energy. But conservation cannot overcome this scale of drought and water shortage. Rationing appears the last option available, and it holds the potential of dramatically curtailing economic activity.

Rationing means that people and businesses will have to reduce their economic activities due to a lack of water. One obvious impact will be a lack of water to serve the approximately 227 million domestic person trips annually to California that generates over $100 billion in visitor spending. It has the potential to impact the operations of California's tech companies that the rest of the U.S., and the world, depend on to run their economies. It will certainly mean less food sourced from California with higher prices at grocery stores across America.

The cost of climate change denial

California is unfortunately positioned to become the first case study on the cost of climate change denial. If California’s water crisis reduces its economic activity by 20 percent, that would equate to a $500 billion decline in our nation’s gross domestic production. This scale of economic decline would represent significant national job loss. It would represent significant food inflation from lost production. It would increase the national deficit from lost tax revenues from California. It would circumvent all the work by the Federal Reserve, Congress and the president to restore economic growth following the Great Recession.

My guess is that California will address this crisis through technology. Over the long term, the state will accelerate its adoption of zero net buildings. Creating economies of scale through state-wide adoption will drive the cost of smart water technology to affordability. New companies will be born, and California will become a global supplier of smart water technologies. But that is the future, after much economic pain tied to the consequences of climate change. The storm cloud on the immediate horizon is the potential first national economic crisis tied to global warming. The forecast is for a very hot political season over whether our country can deny climate change any longer.

Image credit: Flickr/docentjoyce

Bill Roth is an economist and the Founder of Earth 2017. He coaches business owners and leaders on proven best practices in pricing, marketing and operations that make money and create a positive difference. His book, The Secret Green Sauce, profiles business case studies of pioneering best practices that are proven to win customers and grow product revenues. Follow him on Twitter: @earth2017

Starbucks 'Race Together' Conversation a Lesson for Brands

Starbucks is a company that both irritates and inspires, depending on your perspective. Its recycling and waste programs are little more than laughable. An attempt to spread cheer via hashtags turned into a jeering spree over accusations it was a tax evader. But here in the U.S., it is one of the more progressive employers, offering health care to its part-time workers and welcoming LGBT employees. It even earned the wrath of politicians for calling for an increased minimum wage and publicly supporting the Affordable Care Act. The company does not shy away from social issues, and that includes “Race Together.”

In a move that is about as anti-Milton Friedman as a business can go, Starbucks has decided to launch a dialogue about race. Bringing up the emotions that have been brought up in places including Ferguson, Missouri, Oakland, California, and New York City, CEO Howard Schultz said in a statement: “We at Starbucks should be willing to talk about these issues in America. Not to point fingers or to place blame, and not because we have answers, but because staying silent is not who we are."

This is a pretty bold move for a company that caters to a clientele whose daily highlight is showing how sophisticated they are by ordering the most complicated drink at the strip-mall Starbucks drive-thru, so they can show up at the office with a tony white cup in their hand. And it flies in the face of conventional wisdom about business in that companies should be making profits, not statements and commentary about society.

The initiative grew out of internal conversations. According to the company, more than 2,000 Starbucks (enter word here: associates, partners or employees) have discussed racial problems at various open forums across the country. Some baristas said they wanted to make a move to raise awareness, foster empathy and encourage compassion among customers as well as their fellow employees. Baristas in large cities that have been past or present centers of racial tension, including Los Angeles, Chicago, St. Louis, New York and Oakland, California, began writing “Race Together” on Starbucks cups. The nationwide campaign started on Friday, and Starbucks has taken out full-page ad space on USA Today and the New York Times to get the word out. So, is the company going to make a difference?

So far this campaign has been about as productive as a discussion on race relations between Al Sharpton and Donald Sterling. The company has about a 40 percent minority workforce within its U.S. stores, but most of the images I have seen feature white people — including on the company’s press release. So far I have not seen any “race together” scripts in my town, but Fresno, California is a city that was largely built on the efforts of Armenians (who were not considered “white” when they first settled here and land covenants restricted them from buying property within the town limits) and then Mexicans (who worked on the farms that were eventually sold at top dollar so McMansions could be built). The customer who waltzed in from the adjacent Coach store or Banana Republic is going to be in no mood to start a conversation of substance. The same can be said for much of the country.

The upshot is that, for the average Starbucks employee who is quickly criticized for mishearing a name over the sounds of whirring blenders and blasting espresso machines, launching a conversation about race is about as appealing as telling a customer they have run out of sugar-free hazelnut syrup or soy milk. When your day is spent with cries that the chai is “too watery” or the latte is “too milky” (complaints I have overheard), or a customer is enraged because their $2 cookie crumbled after warming (when they were warned it would crumble), talking about race is not going to happen. Plus those same customers are often in a hurry because they have to rush and grocery shop in that nearby purveyor of fine goods for wealthy white people, Whole Foods. As one publication explained, perhaps Starbucks is not the place for this conversation to happen.

By the way, a tweet I came across mentioning the white hands in this “Race Together” campaign has produced its own snark, with one guy retorting, “Y'all realize that every commercial on TV that has a burglar is always a white guy now, right?” And that is just the start of it. You cannot blame Starbucks for trying, as it is a bolder move than most companies would be willing to make on a subject that makes many people uncomfortable (unless they are in an online forum). But based on the history of brands trying to launch a conversation, especially with social media, you cannot be surprised the effort is failing. But at least the satire on Twitter and elsewhere is amusing.

Image credit: Starbucks

Based in Fresno, California, Leon Kaye is a business writer and strategic communications specialist. He has also been featured in The Guardian, Clean Technica, Sustainable Brands, Earth911, Inhabitat, Architect Magazine and Wired.com. When he has time, he shares his thoughts on his own site, GreenGoPost.com. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Canadian Grocer Loblaw to Sell 'Ugly Fruit'

If you have traveled to regions such as the Balkans, India or rural Latin America, the appearance of misshapen fruit and vegetables everywhere would have hardly surprised you; and of course, they are delicious. But shopping trends on both side of the Atlantic have led consumers to believe fruit should be uniform in color and shape.

One reason why food waste in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom hovers around 40 percent is because misshapen or “ugly" fruit is tossed into the refuse bin. Some retailers have tried to stop this trend, but consumer habits and marketing strategies die hard. Now a Canadian grocer, Loblaw, is selling misshapen produce at some of its outlets in Ontario and Quebec.

The company will sell the produce, starting with apples and potatoes, under its generic “no name” moniker.

Like many food companies, Loblaw first tried to deal with misshapen fruit by processing it into juice, sauces or soups. But those tactics can only go so far, and if you've watched any supermarket employee in action at a produce section, those oddly shaped fruits or vegetables often get tossed aside.

Instead of throwing such produce away, Loblaw will sell it at a discount. The company says it will sell the apples and potatoes at a price 30 percent lower than similar fruit without blemishes or odd curves. In a press statement, Ian Gordon, a vice president of Loblaw Companies, said: "We often focus too much on the look of produce rather than the taste. Once you peel or cut an apple you can't tell it once had a blemish or was misshapen.”

More consumer education and genuine efforts will be needed from food retailers if programs like this will scale and become successful. According to a United Kingdom nonprofit, Waste & Resources Action Program (WRAP), food waste is costing countries across the world US$400 billion annually. If this trajectory does not stop, the growing global middle class could cause that figure to increase by another US$200 billion by 2030. Instead of developing new farmland in pristine regions of Africa or South America, or fantasizing about uber cool-looking vertical urban farms in San Francisco or Brooklyn, plenty can be done to stop food waste across the entire supply chain.

Waste diversion programs are a start, but a campaign like Loblaw’s will take some effort. When “ugly fruit” was sold at a French retail chain, Intermarché, the company watched them fly off the shelves — but had to make smoothies and soups with them first to convince customers that they were just as good.

Image credit: Unsplash