H&M To Introduce Denim Line Made Using Recycled Cotton

Fast fashion rightfully receives criticism for being hard on the environment. But some fast fashion can be environmentally friendly, as H&M is keen to prove with a new product roll-out.

Next month, the clothing retailer will introduce new denim pieces made using recycled cotton. The company will introduce a total of 16 new denim styles that incorporate recycled cotton from textiles collected in through its in-store Garment Collecting Initiative. The denim pieces include men's, women's and child's styles, and they will be available in stores worldwide and online.

There is a very good reason why H&M incorporates recycled cotton into its styles. It's seeking to create a closed loop for the textiles it manufactures. Currently, H&M blends in about 20 percent recycled fibers into its clothes. The goal is to eventually get as close to 100 percent as possible.

H&M’s approach to closing the loop is simple and engages the customer. In every store, the company has a Garment Collecting program. It is the first fashion company to launch a global garment collection initiative. The way it works is that any customer can bring unwanted clothes in, and H&M will recycle them. In other words, you can give new life to that old pair of jeans you considered chucking in the garbage. Remember the old adage your grandparents would say? Well, it’s true: Waste not, want not.

“Creating a closed loop for textiles, in which unwanted clothes can be recycled into new ones, will not only minimize textile waste, but also significantly reduce the need for virgin resources as well as other impacts fashion has on our planet,“ said Karl-Johan Persson, CEO of H&M, in a statement.

H&M estimates that up to 95 percent of the thousands of tons of textiles thrown away every year could be either re-worked or recycled. In the U.S. alone about 12.4 million tons of non-durable textiles were generated in 2013, making up 4.9 percent of total municipal solid waste (MSW), according to the EPA. The recovery rate in 2013 for all non-durable textiles was only 14.8 percent.

In a recent report from the Rainforest Action Network on the impact of the fashion industry on the environment, namely deforestation, H&M received recognition. The report mentioned that a number of brands have taken action and have public commitments to protect forests. H&M is one of those brands.

In April 2014, H&M announced its commitment to stop sourcing fabrics derived from endangered forests and promote the use of fabrics from Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-certified plantations, or FSC-certified forest found outside endangered and ancient forests.

Image credit: H&M

Investors Pressure Food and Beverage Companies To Manage Water Risk

Water is the stuff of life. We need it to live. But California doesn't have as much of that stuff to go around, as the state is in its fourth year of drought. There’s no doubt that water crises are a major risk. Earlier this year, the World Economic Forum rated water crisis among the top five global risks facing society.

Food and beverage manufacturing requires a significant amount of water, which means businesses have an opportunity for water use reduction.

To that end, more than 60 North American and European investors, managing $2.6 trillion in collective assets, sent letters to 15 food and beverage companies this month, calling on them to manage water risk. Some big-name companies received the letters, including Archer Daniels Midland Co., Dean Foods, Dr. Pepper Snapple Group, Monster Beverage and Kraft Heinz Co.

In one of the letters, addressed to Dean Foods, the investors state that they believe “global water risk management is a critical aspect of financial risk oversight in the food and beverage sector.” The letter goes on to point out that Dean Foods may be exposed to risks that “could substantively jeopardize the sector’s short- and long-term ability to operate.”

Ceres released a report a few months ago on how the food sector is managing water risks. Titled Feeding Ourselves Thirsty, the report found that only 30 percent of the 37 major food companies surveyed even considered water risks to be a part of major business-planning activities and investment decisions. The companies that were sent letters by investors all scored poorly in Ceres’ report. Take Archer-Daniels Midland, which scored a 10 out of 100, while Monster Beverage scored a mere one point. Here are the scores for the other companies:

- Dean Foods: 13

- Dr. Pepper Snapple Group: 15

- Kraft Heinz Co.: 6

Why are some companies just not realizing that water risk management should be a priority? Earlier this summer, I interviewed Eliza Roberts, manager of the water program at Ceres, for an article about the report. Roberts told me that since water is viewed as cheap “it’s seen as limitless.”

She added, “When something is cheap and seen as limitless, it’s just not going to be valued.”

There is a bit of good news. The severity of California's drought is starting to change how water is perceived. “It’s becoming clear to all with the drought in California that water is not limitless and that water scarcity can have a real impact on business operations and bottom line,” Roberts told me. “So, additionally, as supply goes down and demand increases, it’s becoming clear that water may be cheap for now, but this is likely to change.”

There’s more good news: The pressure that investors are putting on major food and beverage companies may also serve to change perceptions of water. That's something those of us in drought-stricken California will cheer.

Image credit: Flickr/docentjoyce

New York Times Gives Unilever a Mister Softee

Brad Edmondson

The story on the relationship between Unilever and Ben & Jerry's that ran in Thursday's New York Times isn’t really hard news. It’s the Mister Softee version of what really happened.

What the story leaves out is what Unilever does not want you to know. To save money, Unilever executives ordered the recipes for Cherry Garcia and other popular flavors changed shortly after it acquired Ben & Jerry’s in 2000. The company did it without telling the independent board of Ben & Jerry’s, even though going behind the board’s back was prohibited by the legally-binding Sales Agreements. The cherries in Cherry Garcia “tasted like rubber” for several years, according to board member Pierre Ferrari; chunks got smaller, and there was more air in the mix. Scoop-shop owners noticed the differences immediately and protested, without effect. The shop owners started filing lawsuits.

In 2008, after years of stonewalling by Unilever and frustration in Vermont, the independent board told Unilever it had breached the agreements and was required to change the ingredients back. In other words, the Vermonters threatened to take action against the company that owned them. Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield almost went on a publicity tour to promote a protest flavor called “Unilever Squash,” because Unilever was squashing the company they founded.

If the dispute had gone public, it could have destroyed the brand's image. But at the last minute, Unilever came to the table, started taking the Sales Agreements seriously, named Jostein Solheim CEO of Ben & Jerry’s, and gave him the authority and the money to pursue the social mission for real. The entire story is told in the last third of my 2014 book about the social mission of Ben & Jerry's, "Ice Cream Social."

Now, don’t get me wrong — Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever since 2009, has been working hard to push the world’s second-largest food company toward sustainable and ethical business practices. The main point of the Times story is correct. The social mission of Ben & Jerry’s is going strong. Also, Mister Softee is great New York City ice cream. But it’s soft ice cream. Don't forget the hard story.

Image credit: Flickr/Alison Fayre

Based in Ithaca, New York, Brad Edmondson is the author of "Ice Cream Social: The Struggle for the Soul of Ben & Jerry's." He is also an award-winning journalist and business consultant who helps his clients understand and benefit from social change. His writing appears regularly in national magazines, including AARP and The American Scholar.

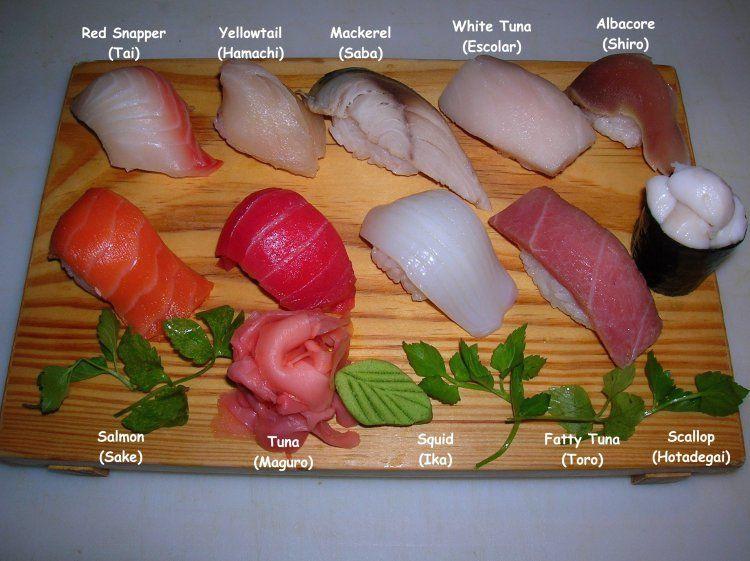

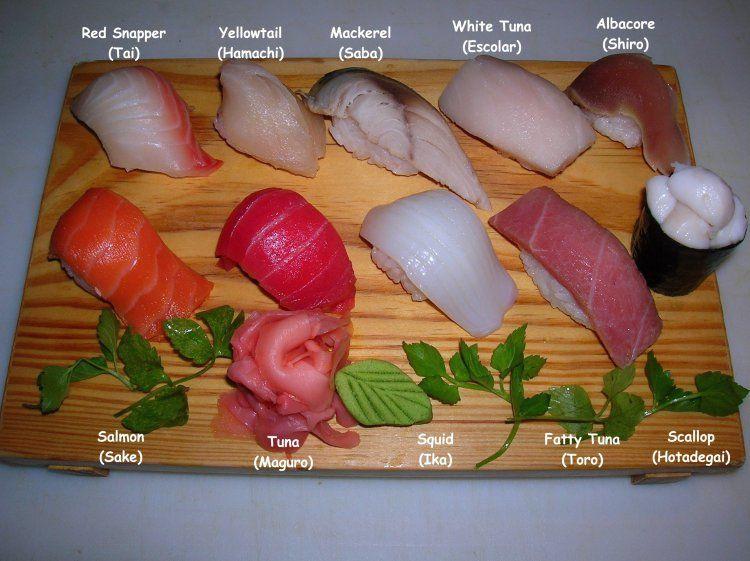

Is That Grouper on Your Plate? Seafood Fraud Hits Diners Hard

By Jerry Nelson

For decades, sushi fanatics could relax in knowing that their carp was mercury-free and fresh. Now, the "fruits of the sea" are not what they appear.

Seafood fraud is flourishing and ranges from mislabeling traditional menu items to overcharging customers.

The stakes have become so significant that a fundamental piece of the Trans-Pacific Partnership is seeking a mutual commitment to stop illicit fishing and damaging supports.

In June, the Obama administration published a new fleet of actions intended at restricting black-marketing fishing and other sorts of seafood fraud.

Types of fraud

Seafood fraud is yet another type of fraud that consists of several forms but boils down to one idea: the sticker on the wrapper does not correctly represent the product within. Even something as seemingly benign as swapping native fish with farm-raised fish is fraud.

Species swapping is another example. For example: Some restaurants sell "white tuna" but substitutes it with escolar, also called the "Ex-Lax Fish."

One fraudulent activity is common but legal and simple: name the fish with something other than a fishy sounding name. The FDA keeps a list of agreeable names, and some of the original names may shock you. "Orange" was first called "slimehead," as just one example.

Mislabeling makes up the largest percentage of fraud being fought inside the industry.

Mislabeling

In 18 years, Trey Knotts, a forensic scientist, has seen over 2,000 catfish filets in disguise.

Recently he's seen a growing number of mislabeled species coming in at a weight of up to a half-million pounds per shipment.

"There are companies importing millions of pounds of fish under fraudulent labeling," Knotts says.

Less than 1 percent of imported seafood is inspected for mislabeling. Knotts points out that the NOAA has less than 100 inspectors. "If you consider the coastline of America, it's a massive amount of territory to be covered," he says.

What is being done with the leaky seafood system? Research conducted by Kimberly Warner of Oceana exposed the size of the problem. One of the loftiest undertakings so far will be for federal agencies such as the NOAA and FDA to coordinate investigations into seafood fraud. With new tools — such as Grouperchek — the government and private industry seem to be close to joint-fighting mislabeled seafood.

Foreign fisheries in countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, Canada, China, Ecuador and Vietnam are unanimously blamed for seafood fraud. Seafood from these countries come mislabeled from unregulated fish farms. The biggest offenders are Thailand and Vietnam with endless supplies of Asian catfish available for export and labeled as grouper or other in-demand fish.

With the majority of fraud originating overseas, American regulators are focusing their attention on those imports. In December 2014, a presidential task force started began to recommend how the government could best fight seafood fraud. Recommendations included increased international collaboration on labeling and highlighted an urgent need for improved seafood tracking.

A 1976 law, the Magnuson-Stevens Act, regulates fisheries and controls overfished species such as speckled hind, an endangered fish often labeled as grouper. The law also protects the overfished Atlantic halibut, often sold as Pacific halibut.

The daily contact with mislabeled fish has made Knotts wary about seafood fraud even when he's not at work. He rarely brings his dinner into the lab for testing, but his work has increased his suspicions.

"Each time you see grouper on the list of options, you go, 'hmmmm ... ,'" he says.

Leaders fighting seafood fraud

Oceana has been the leader in exposing seafood fraud globally. In America, Oceana led a several studies to determine the size of the problem. The Oceana seafood fraud report collected 1,200 seafood samples from over 650 retail outlets in 20 states to determine the validity of their labeling. DNA testing found that 33 percent of the samples analyzed were mislabeled.Oceana's campaign moved President Obama to establish the task force that has started making recommendations to stop seafood fraud.

Tampa-based PureMolecular has developed fist-sized machines that can help retailers determine the actual species of fish being purchased or sold.

John Paul, PureMolecular's CEO, said the technology produces results within 45 minutes. Genetically, only 0.02 percent of imported fish is analyzed. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration tests take up to a week to produce results

How consumers can protect themselves

While the fishing trade persists in being something of an untamed Wild West, consumers can guard themselves against eating contaminated or mislabeled fish. Activists are starting to lead a demand for seafood transparency that is reminiscent of the change in dairy that demanded milk without added steroids be available.

Consumers can demand to know where and how their seafood is caught. Asking lawmakers to require stricter penalties for mislabeling and showing support for the seafood fraud elements of the Trans-Pacific Partnership are two more actions that will go a long way to promoting sustainable fisheries.

In the meantime, consumers should be careful what goes on their plate.

Don't fall for the "bait and switch."

Jerry Nelson is an American freelance writer and photographer covering social justice issues globally. When not traveling, he lives in Buenos Aires with his wife Alejandra and their cat, Tommy. Follow him on Twitter.

China's CO2 emissions 'substantially over estimated'

China's carbon emissions have been substantially over estimated by international agencies for more than 10 years, according to research co-led by the University of East Anglia.

The revised estimates of China's carbon emissions were produced by an international team of researchers, led by Harvard University, UEA, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Tsinghua University, in collaboration with 15 other international research institutions.

The team re-evaluated emissions from the burning of fossil fuels and cement production from 1950-2013. They used independently assessed activity data on the amounts of fuels burned and new measurements of emissions factors - the amount of carbon oxidised per unit of fuel consumed - for Chinese coal.

Lead UK researcher Prof Dabo Guan, of UEA's School of International Development, said the key contributor to the new estimates was fuel quality, which for the first time was taken into consideration in establishing emission inventories - something the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and most international data sources had not.

“China is the largest coal consumer in the world, but it burns much lower quality coal, such as brown coal, which has a lower heat value and carbon content compared to the coal burned in the US and Europe,” said Prof Guan.

“China is one of the first countries to conduct a comprehensive survey for its coal qualities and a global effort is required to help other major coal users, such as India and Indonesia, understand their physical coal consumptions as well as the quality of their coal types.

"Our results suggest that Chinese CO2 emissions have been substantially over estimated in recent years. Evaluating progress towards countries' commitments to reduce CO2 emissions depends upon improving the accuracy of annual emissions estimates and reducing related uncertainties. These findings represent progress towards improving estimates of annual global carbon emissions."

'Reduced carbon emission estimates from fossil fuel combustion and cement production in China' was published in Nature last week.

Energy Storage is Coming Home

By Max Bloom

Driven by technological innovation and economies of scale, the installed price of solar photovoltaics has plummeted in recent years. Combined with federal and state incentives, and creative financing models, these low prices have ushered affordable solar power into the mainstream. In 2014, 6.2 gigawatts of solar PV were installed in the U.S. alone, 20 times the amount installed in 2008.

Meanwhile, residential battery storage, a mainstay in the early days of solar PV, has largely been relegated to the fringe as an expensive, rarely-used backup. Most end-users now connect to the electric grid, relying on utilities to provide power when their PV systems don’t. These users employ the grid as a robust, always-available “battery” to which they enjoy free access, obviating the need to pay for their own storage solutions.

But that paradigm may be about to change. Anticipating fundamental revisions to residential rate structures, Enphase, the PV microinverter market leader, is preparing to launch a new AC-battery residential storage solution in 2016. Should projected rate changes come to pass, the Enphase AC Battery system, combined with solar PV, could present homeowners with a compelling economic proposition. With over 8 million microinverters deployed worldwide, Enphase may be in a unique position to bring residential battery storage to the masses.

While the residential energy storage market has yet to blossom, the utility-scale market is booming. U.S. energy storage capacity grew by 40 percent from 2013 to 2014, with 90 percent of that new capacity deployed in front of the meter (i.e., utility-scale). Storage in all markets combined is expected to grow another 300 percent in 2015.

Residential and commercial and industrial (C&I) storage may represent just 10 percent of the overall market today, but a recent GTM research report predicts behind-the-meter storage (residential, commercial, education, military or nonprofit) will account for 45 percent of the market by 2019.

Because of differences in rate structures between the C&I and residential markets, and what’s known as “demand charges,” the C&I storage market currently makes up the lion’s share of non-utility-scale energy storage. In addition to paying for the quantity of energy they use, just as residential customers do, C&I customers also pay demand charges that are based on the 15-minute period in which the customer uses the most power in a given month. Demand charges can make up 30, 50 or even 70 percent of a company’s electricity bill and run into many thousands of dollars per month.

“Peak shaving,” i.e. charging a battery storage system when energy is cheap (or free with solar PV) and then discharging the battery when demand is at its peak in order to minimize steep demand charges, is a key economic driver for C&I energy storage.

San Francisco-based GELI (Growing Energy Labs, Inc.) has developed software that enables companies to optimize the economics of their energy storage systems. “Our software uses predictive analytics to follow a building’s load, and when it hits a certain threshold we use the battery to negate additional use and lower demand charges,” says Andrew Krulewitz, GELI’s director of marketing and product. “Our bread-and-butter market right now is demand charge management for commercial and industrial customers with load from 50 kW all the way up to a megawatt.”

Time-of-use (TOU) pricing structures, common for C&I customers and increasingly available to residential customers, provide another economic incentive for storage systems. Demand Energy, a turnkey provider of behind-the-meter energy storage solutions in the commercial and industrial space, helps companies arbitrage their energy production and consumption through “time-shifting.” “With time-of-use, you can store and shift solar power,” notes Erick Peterson, Demand Energy’s vic president of marketing and business development. “Any excess solar production that you don’t need in the building you just store and time-shift it out to a later period in the day [when rates are higher].”

The value proposition for residential energy storage today is where solar PV was six or seven years ago, and the factors that led PV to mass affordability will likely have a similar effect on storage. Battery costs have declined by 80 percent in the past decade, and dozens of startup companies are now competing to develop safer, more efficient and less expensive battery chemistries.

The economies of scale introduced by Tesla’s Powerwall battery system and its Gigafactory battery manufacturing plant in Nevada will place additional downward pressure on residential energy storage costs. Incentives like the federal ITC (at least through 2016) and California’s SGIP program (at least through 2019) will further sweeten the deal for potential purchasers of home-based energy storage.

But the key drivers that will make the economic case for residential energy storage are higher energy prices and changes to residential rate structures. “Everything is signaled through pricing,” notes Greg Wolfson, director of storage products at Enphase. “At the end of the day, customers don’t want a storage system. They want to manage their bill.” High energy prices incentivize the purchase of both solar PV and energy storage systems. When prices are high, homeowners save money when they use either direct PV power or stored excess PV power instead of expensive utility-generated power.

While net energy metering (NEM) has helped to build the economic case for PV, the opposite is true for storage. It is the demise of NEM that will encourage the adoption of residential energy storage.

NEM enables solar PV system owners to sell their excess power back to the utilities at retail rates, increasing the economic return of their PV systems. Some utilities propose paying lower wholesale rates for excess power sent to the grid or even eliminating NEM altogether (Hawaii’s HECO utility). The less utilities pay for excess generation sent back to the grid, the more sense it makes for PV system owners to store that excess and use it themselves. “Without net metering, solar over-generation is useless to you because you’re not being compensated for what you generate,” notes GELI’s Krulewitz. “With a battery, you can capture [and later use] all that over-generation.”

Some utilities are starting to propose TOU rate structures (Southern California Edison) and even demand charges (Arizona’s SRP utility) for their residential customers. All of these changes in rate policy – a weakening of NEM, adoption of TOU rates or the institution of residential demand charges – bolster the economic case for residential storage.

Although the Enphase AC battery system will only operate when connected to the grid, the company is looking ahead to a time when revised rate structures support an economic case beyond backup. “The big driver at this instant in time in the United States, in the main, is for emergency power backup,” acknowledges Enphase’s Wolfson. “That’s not where we’re focused. Our focus is on the economics – not energy independence, but energy economics.”

Energy prices and rate structures that already exist in other countries portend the economic viability of home energy storage sooner rather than later. “If you live in Australia, or Hawaii, or Germany, or Japan or the Netherlands or the UK … or potentially in Arizona, where demand charges are being proposed or implemented, then [residential energy storage] does make economic sense today,” notes Wolfson.

Enphase plans to rollout its first AC battery systems next year in Australia, where rate structures are already favorable for storage. “In Australia, they don’t have a lot of incentives,” says Wolfson. “They slashed marginal rates to almost wholesale rates, so there’s very little economic value in exporting what you generate.”

Other companies smell blood in the water and are introducing their own residential energy storage solutions. JuiceBox Energy installed its first 8.6 kW Lithium-ion, AC coupled system in a California home earlier this year. Next year, SolarEdge will offer a DC coupled solution that combines a Tesla Powerwall battery with a SolarEdge inverter.

Both the JuiceBox and SolarEdge systems enable islanding, allowing the PV and storage systems to power the home even when the grid goes down. The Enphase system must be connected to the grid, and cannot be used as a grid backup.

Neither Enphase nor SolarEdge has released pricing information for their storage offerings, but the $3,000 cost of the 7 kW Tesla Powerwall battery (around $7,250 installed with an inverter) might offer a clue. Tesla’s Elon Musk suggests he will be able to produce Powerwall batteries at scale for $250 per kilowatt, putting further downward pressure on new storage system prices. Software like GELI’s, used to optimize the economics of storage systems, will be available in the residential market and may add a bit to system cost.

The typical homeowner’s relationship to electricity has been to flip the switch and pay the monthly bill. In the near future, the consumer’s relationship to electricity – where it comes from, what it costs and why – will become much more intimate. When customers realize they can save money by generating and storing their own renewable energy, and use software to determine when it is most advantageous to use it, then the market for residential energy storage will truly come alive.

Image credits: 1) Enphase 2) Tesla 3) Juice Box

Max Bloom is a Renewable Energy Marketing Communications Director based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Marine Stewardship Council Develops a New Chain-of-Custody Monitor

The seafood industry is truly a global business. More than 150 million tons of seafood hit the markets each year across the globe. According to the Marine Stewardship Council, a full half of that seafood was traded by developing nations. And although the U.S. and Canada are major purveyors of the world's seafood market, their laws governing sustainable fishing methods don't control how seafood is harvested by companies and contractors in those developing countries.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, 85 percent of the world's fisheries are already at the brink of overfishing. "Pollution, poorly planned development and the effects of climate change have also contributed to the degradation of the underwater environment," says the WWF, which like the MSC has been sounding the alarm for more oversight, better fishing methods and increased habitat conservation in an effort to protect endangered and threatened species and fish stocks

There have been various strategies developed over the years to this end. Last year we reported on the efforts of Monterey Bay's Seafood Watch Program to give consumers a more informative tool for selecting sustainably-fished products. Its products guide and downloadable app serve as one answer for consumers who want a better peek into the industry's impact on the world's oceans.

The MSC is also working on that concept -- only from a different angle.

"Over the past two years we have been piloting a new traceability tool, the MSC Online Transaction Solution (MOTS)." The tool will be the first of its kind, designed to "securely handle and verify information about seafood supply chain transactions on a global scale." Its job will be to cross-check seafood transactions within the supply chain, adding more accountability into the fishing and sale of the world's ocean stocks.

Last week the MSC reached out to industry stakeholders asking for feedback on the new tool so it can determine whether the tool would be applicable for the entire program. The tool has already been piloted with 22 companies in China and the European Union, and the MSC invites a final round of industry members’ feedback before the broader roll-out. If successful, some 3,000 supply companies in 60 countries that handle ecolabel-certified products will employ the new tool in 34,000 locations around the world.

The organization targeted 2017 for a voluntary roll-out date for the MOTS and a potential mandatory roll-out of 2018. It is also focused on raising the number of fisheries and farms signed up on its certification program. Currently 250 fisheries are signed up; the organization hopes to raise that number to 1,000 by the end of the decade. According to MSC, DNA testing of samples show that "99 percent of MSC-labeled products are correctly labeled, demonstrating the integrity of the current system." The new MOTS tool is being designed to work in concert with MSC's ongoing chain-of-custody program.

The MOTS tool is open for public consultation until Sept. 2. You can review information on the project and anticipated roll-out schedule on the MOTS program page.

How the Extractives Industry Hurts Indigenous Women

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the August issue of Green Money Journal.

By Rebecca Adamson

Extractive industry projects may not be created to victimize women, but violence against women has become a major by-product of these project operations. Rampant exploitation of women happens when thousands of mostly male workers are housed in makeshift “man camps” located at the sites of company operations.

For example, North Dakota’s Bakken oil field has boomed: Over the past five years, it has increased daily oil production from 200,000 barrels to 1.1 million barrels, becoming the second largest oil-producing state in the country. Thousands of highly paid workers have flocked to the region. Within two years, the combined influx of cash and oil workers has tripled the rate of murders, aggravated assaults and robberies. Sex crimes, rape, prostitution and human trafficking have increased by 20.2 percent. Business Insider summarized the region thusly: “[L]aw enforcement says Bakken is a made-to-order market for sex."

Violence against women is widespread across extractive industry site operations. It is social pollution as toxic as any chemical released into the environment. Yet in the socially responsible investing (SRI) community, of the three principal criteria — environment, social and governance — metrics are proceeding the slowest in terms of measuring impact, corporate accountability and investor risk. Currently, the Securities and Exchange Commission does not require corporate securities reporting on community relations or human rights due to their perceived lack of material relevance. However, just last year, EY (formerly Ernst and Young) elevated the “social license to operate” to the third place on its list of the greatest business risks to the mining industry.

John Ruggie, author of the U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (the Guiding Principles), told Business Ethics that “for a world-class mining operation … there’s a cost somewhere between $20 million to $30 million a week for operational disruptions by communities” and that the time it takes to bring oil and gas projects online has “doubled over the course of the past ten years, creating substantial cost inflation”. Additionally, “analysis by Environmental Resources Management of delays associated with a sample of 190 of the world’s largest oil and gas projects (as ranked by Goldman Sachs) found that 73 percent of project delays were due to “above-ground” or non-technical risk, including stakeholder resistance."

The problem is that current efforts to engage the private sector on human rights are largely driven by the Guiding Principles, which offer a rigidly “top down” framework that does not account for local dynamics such as the cumulative impacts of multiple companies operating in close proximity to a community, or the spikes in violence against women. Furthermore, the Guiding Principles mention women, along with indigenous peoples, only in passing, thereby largely excluding them from the corporate social responsibility conversation. The resulting lack of guidance and metrics enables companies to disclose minimal information about their social impacts—especially on vulnerable groups — which limits investors’ ability to measure social risks and keeps nefarious social costs invisible and running rampant.

Published in November 2014, First Peoples Worldwide’s Indigenous Rights Risk Report (IR3) offers a case study for measuring one of the most pressing social risks to the extractive industries — indigenous peoples’ rights — from the bottom up.

Designed over a two-year process with input from indigenous leaders and activists, financial analysts, and industry experts, IR3 assessed 52 U.S. oil, gas and mining companies to identify where their projects overlap with or impact indigenous peoples, and rated each project’s risk exposure for failing to obtain free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC). FPIC is recognized in the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as indigenous peoples’ right to give or withhold support to corporate activities that affect them. Eighty-nine percent of the 330 projects assessed had medium- to high-risk exposure (a searchable database of the scorecards is available on First Peoples’ website). By assigning quantitative risk scores at the project level using a methodology designed to capture the complex undercurrents within both communities and companies, IR3 provides a framework — and three key lessons — for designing social metrics that can be applied beyond just indigenous peoples.

The first lesson is that the results of preliminary back testing indicate a possible correlation between the companies’ average project risk scores and their market growth between 2010 and 2014. Companies with lower average project risk scores outperformed companies with higher average project risk scores by 4.21 percent. There are some caveats to this figure resulting from our small sample size, but it’s an important step in demonstrating the connection between corporate social and financial performance.

The second lesson is that most companies operate with no governance structure whatsoever for addressing social risks. One of IR3’s risk indicators is risk management, which rates a company’s capacity to identify, manage and mitigate social risks at the board level. Forty-eight of the 52 companies have virtually nothing in this regard. They have no board committees with community relations or human rights in their mandate, or board members with community relations or human rights expertise. Without the governance structure or company capacity to identify, manage, and mitigate social risks, investors are left with a Management by Headlines approach, and virtually all communities that host or are proximate to extractive projects are in danger—as we’ve seen in case after case of violence against women.

Reports of Native American women and girls being trafficked to the Bakken has put the Fort Berthold Reservation on high alert, but how are the companies operating in the region responding? They’re not. Companies including Apache, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Hess and others have taken zero responsibility for their workers’ collusion in the growing sex trade, increased drug violence, and general crime wave in Fort Berthold, North Dakota, over the past two years -- let alone the rest of the region.

While some companies in the region are making efforts to reduce flaring and improve transparency, no substantive dialogue is taking place about social impacts. This trend of neglecting social risks has permeated corporate interactions with communities across the globe.

Read the full article from the August 2015 issue of GreenMoney Journal here.

Article by Rebecca Adamson, an Indigenous economist, is Founder and President of First Peoples Worldwide (www.firstpeoples.org), the first U.S.-based global Indigenous Peoples NGO, which makes grants and provides technical assistance and advocacy directly to Indigenous-led development projects. Ms. Adamson has worked directly with grassroots tribal communities, both domestically and internationally, as an advocate of local tribal issues since 1970.

She established the premiere US development institute, First Nations Development Institute in 1980 and in 1997 she founded First Peoples Worldwide. Ms. Adamson’s work established the first microenterprise loan fund in the United States, the first tribal investment model, and, a national movement for reservation land reform.

Why Partnerships are Key to Water Security

By André Fourie, SAB Miller and Stuart Orr, WWF

This year’s annual World Water Week in Stockholm is happening at a unique moment. In just a few weeks’ time, member states of the United Nations will adopt a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that will define global development priorities for the next 15 years.

The SDGs aim to eliminate extreme poverty, build more equitable and just societies, and keep humanity safely within the Earth’s ecological boundaries. Yes, they’re ambitious. Each of the 17 goals addresses a complex, yet fundamental issue for the well-being of people and the planet. Goal six, which will surely be a major topic in Stockholm, seeks to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.”

While governments are ultimately responsible for the delivery of water, we know it’s a massive challenge in some parts of the world. Conservation and development groups have helped support better management of freshwater ecosystems and expansion of sanitation services. But with such a significant percentage of the world’s water going into corporate and agricultural supply chains, we must both invite and insist that businesses contribute to the solutions envisioned in the SDGs.

Water stewardship provides a strong model for how this might work. Just as the SDGs provide an integrated approach to meeting social, economic and environmental needs, WWF’s approach to water stewardship is about much more than making supply chains more sustainable. Our goal is better governance of a vital shared resource that underpins healthy societies and healthy economies.

We know that companies don't engage in water stewardship to eradicate poverty. They engage in stewardship because poor water governance poses a fundamental business risk, as evidenced by a growing number of reports, surveys and analyses. However, the benefit of stewardship will extend beyond any single company, and improved management of and access to water is fundamental to improving people's livelihoods and well-being.

The SDGs recognize that failing to manage natural resources means lost economic opportunity and squandered human potential. Corporate water stewardship can help achieve these goals by putting the private sector's financial and political power behind good governance. But it’s more than just financial support and technical solutions. If done responsibly, integrating private-sector action into global policy frameworks and local implementation practices makes it possible for companies to contribute considerable resources and expertise to achieving the SDGs.

For SABMiller, the SDGs are an opportunity to expand shared prosperity, because we only thrive as a business if the communities around us thrive. Communities only thrive if ecosystems thrive, and that requires better management of water. It’s an idea that forms the basis of our work, and is a platform for our partnerships with organizations like WWF.

In Stockholm, SABMiller will argue that businesses have to be innovative in forging such partnerships. Business needs to be prepared to forge new relationships and commit to being transparent and accountable in our stewardship practices, even if at times our first advances are treated with caution.

The SDGs are a framework to partner state commitments with the rigor of the private sector and the expertise of NGOs. Successfully implementing the goals requires us to be bolder in exploring how our skills and resources can be combined for the best impact and to achieve real scale. Implementation is, of course, what business does. Add the combined local experience and global perspective of an organization like WWF and the policy and infrastructure support that governments provide, and you have a recipe for scalable, transformational change.

Image credit: Flickr/Vinoth Chendar

André Fourie is Senior Manager of Environmental Value for SABMiller plc. André joined the sustainability team at SABMiller plc in 2013. Previously he was Head of Sustainable Development at our South African business, SAB Ltd. He was formerly the Chief Executive Officer of the National Business Initiative (NBI) for seven years, from 2003. The NBI is a business coalition of 140 leading South African and multi-national corporations dedicated to a sustainable future. He currently chairs the Strategic Water Partners Network (SWPN) in South Africa.

Stuart Orr is Head of Water Stewardship for WWF. Stuart has been with WWF since 2006 and works with the private sector on a range of water related activities, from water footprint to public policy engagement. Stuart has published numerous papers on water measurement, agricultural policy and water-related risk, and is currently co-drafting policy guidelines for the private sector as part of the UN CEO Water Mandate. Stuart has also recently joined the World Economic Forum’s Global Agenda Council for water.

Previous to life with WWF, he researched agricultural rice systems in West Africa and worked for many years in the private sector in Asia and the US. Stuart holds an MSc in Environment and Development from the School of International Development at the University of East Anglia and is currently based in Switzerland where he works at WWF-International as a Manager in the Freshwater Team.

Lessons from a Failed Nonprofit

By Joseph Plummer

It takes a special kind of stupid to start a nonprofit on your own. In February 2011, I was that special kind of stupid. I started a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization more or less on a whim.

As it turns out, you can actually complete most of the paperwork to create an organization and then apply for 501(c)(3) status without talking to a single person. However, before you are granted nonprofit status, your organization must have a board of directors. This begins the expansion of an individual’s vision to other accepting hearts and minds.

Fast forward to Fall 2011, I received the coveted Determination Letter from the IRS granting my organization nonprofit status. At this point, I began talking to schools, nonprofit leaders, elected officials, corporate representatives and university professors with the hope of spreading my vision: solar panels at every school in America. Now four years later in 2015, I have connected with hundreds of people, raised a modest amount of money, and spread my vision a little bit further. I can honestly say that starting my nonprofit was the best decision of my life.

However, there has always been a lingering question in my mind since starting my organization. I once heard someone say that nonprofits should try to make themselves obsolete. So, the question that lingers is: Does your organization need to exist?

When I asked myself this question in 2011, the answer was indisputably yes. This answer is, of course, a combination of truth and youthful spirit. However, after four years, the question is more difficult to answer now.

If I were to approach a nonprofit leader in 2011 and suggest a new initiative, I would have received at best a response like “that’s an interesting idea, good luck." Today when I approach the same nonprofit leaders, the best responses are more like “how can we help?” or “we’re in.” Likewise, in 2011 potential corporate sponsors would rarely return emails or calls. Today most companies with respectable corporate social responsibility (CSR) departments will take meetings with me, though they are still slow to give financial support. This progress is great, but it doesn’t answer the question of whether or not the organization needs to exist.

In 2011, a significant number of our partner organizations either didn’t exist or were also recently founded. I have seen some great organizations die, for lack of a better word, over the past four years. I have also seen some wildcard organizations grow into thriving nonprofits. In my humble opinion, success in the nonprofit sector is a function of luck more than anything else. Creativity, hard work, smart work and intentional networking are also significant factors. In any case, my organization has had a torturously mediocre amount of success. It has received dozens of letters of support from local leaders, numerous small grants ranging from $500 to $15,000, and a couple of awards for innovative programs. However, this mild success also does not answer the question of whether or not the organization needs to exist.

So, given the preceding five paragraphs, I am now going to answer the question: Does my organization need to exist? My answer is no. I say this with pain in my heart, with pride in what I have been able to accomplish, and with a precise understanding of how to create greater impact.

In short, after four years, my organization has not been able to breach $100,000 per year in revenue. And, for the type and size of my organization, the amount of time devoted to unsuccessful fundraising really does not make sense. Furthermore, the connections I have made allow me to keep the momentum toward impact that my organization has created by diverting opportunities to other organizations that have the capacity to capitalize on them in ways that my organization could not.

It is interesting to read the obituaries of failed nonprofits. They are inherently gloomy and disheartening. It is as if the nonprofit leader is falling on his or her sword, accepting the shame of defeat. They say things like “we had a good run” or “thanks for the memories” or “it was fun while it lasted." These final newsletters only serve to reinforce the understandings, and perhaps realities, that our nonprofit sector is weak and that being an entrepreneur is risky and often ends in failure.

The truth is the American nonprofit sector is easy. There isn’t much funding, but there are a lot of nonprofits that don’t need much money to operate. There are a ton of nonprofits that operate on less than $10,000 a year. And, if that is your annual operating budget, you really don’t have to risk much to keep your nonprofit running. The nonprofit sector in America is almost failure-proof. You might not be very effective, but it is very easy for nonprofits to exist in America. Being an entrepreneur in the nonprofit sector is not risky.

My nonprofit has reached the end of its journey, because I believe more impact can be achieved through the consolidation of efforts. Over the next few months, I will be transferring the momentum that my organization has created. The weight of my organization will be transferred to other organizations. The nonprofit sector will be stronger, because of the life and death of my organization.

I have compiled a short list of lessons learned for anyone who is thinking about starting a nonprofit. This is not an exhaustive list, but this should help young nonprofit leaders with some of the basics.

1. Have a co-founder or two.

Starting a business is lonely. You are putting your ideas out into the world, and the world is tearing them apart. You are spending time, money and creativity on making an organization work, and the odds are very much against you. Take the time to find someone that cares as much as you and is easy to work with. This will reduce the risk of depression and failure and ultimately make your organization better.

2. Make your brand and organization name a non-thought.

You never want to hear, “Ohhhhhhh, I get it!” That is an indication that they didn’t “get it” right away.

The name that I came up with for my organization was Three Birds. The idea behind the organization was that we were using renewable energy as a catalyst to address three issues simultaneously (education, environment and economy) -- essentially hitting three birds with one stone. This is a nice idea that is great for long conversations with your significant other in front of a fire with a bottle of cheap wine, but when you are meeting a potential funder or organizational partner for coffee, the explanation of what your organization name is all about eats into what might only be 10 minutes of meaningful conversation time.

Also, when deciding on a name for your organization, stay away from metaphors about killing birds, especially when you are working in an environmentally-related profession. And, make sure you are not unintentionally referring to a Bob Marley song.

3. Focus on product: If you have great ideas, turn them into products.

Great products sell themselves. If your organization has a great product, it will sell itself and carry your organization. All you have to do is show people the product in action, and the consumer will do the rest.

Great ideas are different: When you tell someone about a great idea, it will cause them to think about it and in some cases talk about it. And that is a good thing. But it is very hard to convert ideas into money, which is what you need as an organization to survive.

You can sell data, you can sell products, you can sell services, and you can make your ideas part of those things. But you can’t sell ideas alone, because in order for someone to buy an idea, they need to know what the idea is. The nonprofit sector is great at thinking and providing the world with ideas. Most nonprofits advocate, but the great nonprofits are the ones that make themselves obsolete. You can advocate for clean water or you can create a low-cost, portable, easy-to-use water filtration system. Choose wisely.

4. Don’t pitch. Swing.

In the nonprofit sector, you have to fundraise constantly. This means pitching day-in and day-out. This is the inherent failure of the nonprofit sector. The sector that is clearly the least corrupt and most pure is required to spend half its time (at least) begging (whether you are a startup or not).

According to Bloomberg, 8 of every 10 new businesses fail within 18 months. If you are an entrepreneur, this shouldn’t cause you stress. This should give you some relief. What if at the beginning of your endeavor, God were to tell you with 100 percent certainty that you were going to fail and your organization would not exist within five years time? This to me would be an indication that you shouldn’t spend your time and creativity on pitching, but rather on creating great products and solutions. If you are going to be an entrepreneur, recognize that failure is inevitable. Let that give you some peace of mind. And then swing for the fences.

5. Reputation matters.

In the nonprofit sector, the organizations that are competing for the same funding as yours are also the organizations you are most likely to collaborate with. Don’t piss them off. Don’t alienate them. Market to them. Once you have your great product, show them first. They will validate your work and often sing your praises to funders. Your colleagues in other organizations, especially in the nonprofit sector, are your greatest advocates.

6. Funders need to be educated.

Funders aren’t stupid; they just don’t know. Most funders are far from the front lines. They haven’t a clue what is going on from day to day in the world of social change. As a nonprofit leader, you are in the fray every day. Funders need to know where your ideas are coming from. Anecdotes, data and site visits are all great ways to educate funders about what your organization is doing and the impact it is having.

7. Adopt mentors.

People don’t like giving away money, but people love to give away advice. And you need it just as much as the money. Young entrepreneurs especially need wisdom. Find people with scars and ask them how they got those scars. Ask a thousand questions. If you start to hear people say, “Wow, you really thought of everything.” Then you’ll know you’re doing it right.

8. Social media is great for awareness, and pools are great for holding water.

Recognize that social media is not the answer to your funding problems. Social media is really effective at building and sustaining awareness. And, sometimes social media can make some pretty extraordinary things happen. But, for the most part, social media doesn’t move the needle. Steer yourself and your organization away from ideas that rely on social media. Think of social media as a given or a base in a broader integrative marketing strategy.

9. Shrink your board.

Many nonprofits use their board of directors to fundraise, advocate and extend their network. This isn’t a terrible idea, but remember what the primary role of the board is supposed to be: governance.

Governance gets difficult when you have a large board. Unless you have a great network of willing fundraisers and advocates, just focus on making governance as easy as possible. This will reduce headaches as the organization grows. Get governance right, and then think about how the board can help fundraise and network.

10. Volunteer programs don’t scale.

Volunteers are great for one-day events. But they become less reliable for week-to-week engagement. Life happens. Relying on volunteers makes your programs and organizational work less consistent and tougher to plan. Accept the love, time and creativity from volunteers, but don’t build a program around it.

11. Understand the difference between a small bet and a big bet.

Spending 1 percent of your budget on an unsuccessful crowdfunding campaign might be considered a small bet. Spending 40 percent of your yearly budget on prototyping new demonstration tools and products might be considered a big bet. Just remember that any bet you make as an individual or an organization is a small bet when considering the scale of our global challenges.

Image credit: Flickr/yevkusa

Joseph Plummer is a degree candidate in the Executive Master of Natural Resources (XMNR) program at Virginia Tech, expecting to graduate in May 2016. He is the founder of The Three Birds Foundation, a non-profit organization that worked with schools and school districts on renewable energy and sustainability initiatives.