It’s the trick question that has left many of us stumped: from the earliest stages of manufacture to the years driving on the road until they are sent to the junkyard, are conventional automobiles or electric cars cleaner for the environment? While acknowledging that electric vehicles (EVs) emit no emissions when running on our streets and highways, many have assumed that those pesky rare earth metals in their massive batteries and the emissions associated with producing the power canceled out any environmental benefits that their drivers enjoyed.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), a two-year study has provided the answer. The EV is the cleaner option, hands down.

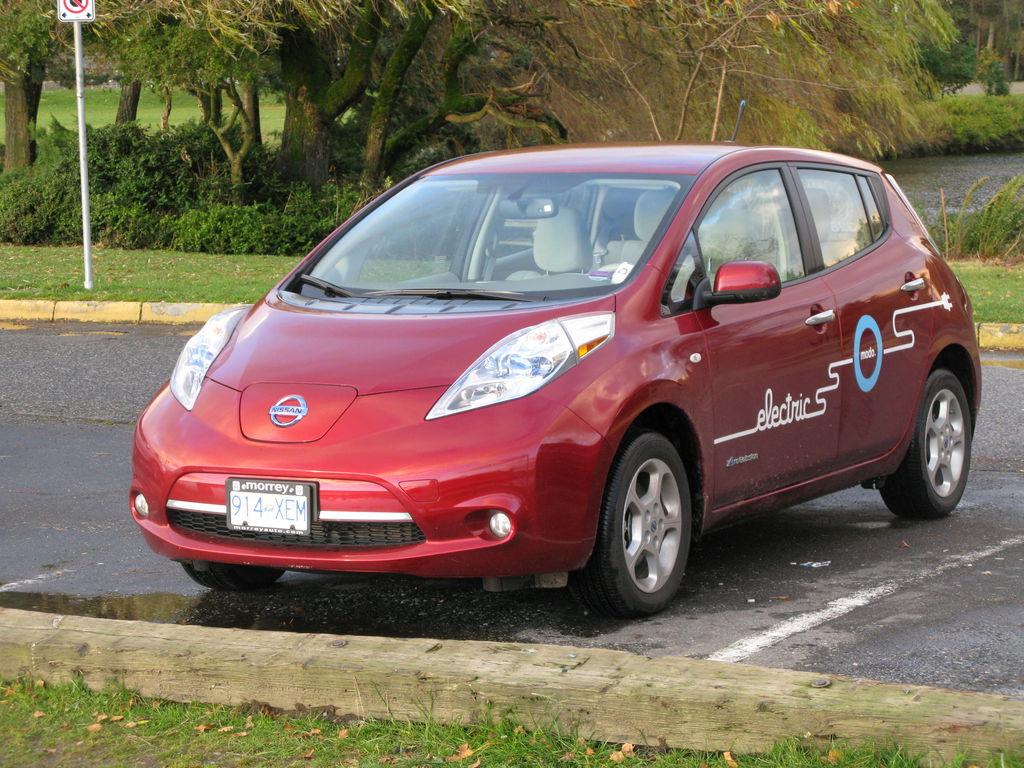

In order to reach that conclusion, UCS researchers evaluated the entire life cycle of an EV based on the two most popular models sold in the United States—the Nissan Leaf and Tesla Model S. Looking at the raw materials needed to make a car, the assembly and manufacturing processes, driving, disposal and recycling, the UCS team compared the emissions of EVs to a similarly sized gasoline-powered automobile, with examples including the Ford Focus, Mitsubishi Lancer Sportback, Kia Forte5 and Volkswagen Golf.

When emissions are measured during the early manufacturing phases, UCS found that the manufacture of EVs at first were less clean than that of conventionally fueled cars. But within anywhere from six to 16 months after both cars have been driven, those early emissions are quickly offset by their cleaner driving. So when comparing these cars’ respective environmental performance over their lifetime, UCS' researchers concluded that an EV will generate less than half of the greenhouse gas emissions compared to those of a gasoline-powered car. For a smaller EV, only 4,900 miles of driving will offset those higher emissions from that vehicle’s manufacture; in the case of a full-sized, long-range EV, those earlier emissions are canceled out after approximately 19,000 miles of driving.

UCS based its assumptions on the fact that both cars would have a 15-year life cycle, with 135,000 miles driven and a weight of approximately 3,000 pounds. The researchers also assumed that in comparison for this study, the average gasoline-powered car would have an average fuel economy of 29 miles to the gallon.

UCS insists that EVs will become even more efficient and therefore, cleaner in the coming years. These cars' environmental benefits will increase as additional sources of cleaner energy fuel the national grid. In regions of the U.S. where much of the grid is still reliant on coal energy, driving an electric car is currently about as efficient as a gasoline-powered automobile that scores 35 to 40 miles per gallon. And in areas where the electricity grid uses cleaner sources of energy (as on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts), EVs' equivalent miles per gallon rates spike even higher. Overall, according to UCS, driving an EV in the U.S. on average produces greenhouse gas emissions equal to driving a gasoline-powered car with a mileage of 68 miles per gallon. To put all these statistics into context, UCS has an online tool that allows users to see how an EV's environmental performance would measure within their zip code.

More needs to be done, however, before EVs can truly make a difference in reducing the U.S.’s carbon emissions. EVs have got to contribute a larger share of vehicle sales than they do now—at the moment they account for less than one percent of sales nationwide. The grid has got to become cleaner and greener as well, though UCS does point out that even in a region dominated by coal-fired power plants, an EV reliant on such power at worst offers a fuel economy of 29 miles per gallon.

Overall UCS is sanguine about the future of EVs, consumer doubt and low oil prices notwithstanding. The convergence of better EV performance, cleaner electricity generation, optimized battery technology and improved battery recycling can help EVs reduce American oil consumption significantly in the coming decades--and of course, less time at the pump.

Image credit: Markus Mayer, Wikipedia

Leon Kaye has written for 3p since 2010 and become executive editor in 2018. His previous work includes writing for the Guardian as well as other online and print publications. In addition, he's worked in sales executive roles within technology and financial research companies, as well as for a public relations firm, for which he consulted with one of the globe’s leading sustainability initiatives. Currently living in Central California, he’s traveled to 70-plus countries and has lived and worked in South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay.

Leon’s an alum of Fresno State, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and the University of Southern California's Marshall Business School. He enjoys traveling abroad as well as exploring California’s Central Coast and the Sierra Nevadas.