By Rob Wolcott

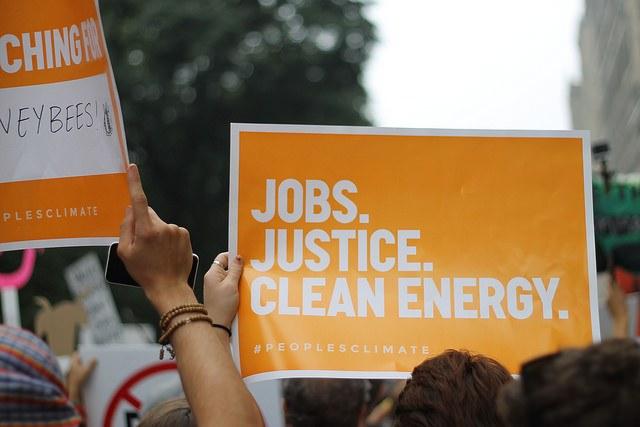

As citizens and world leaders converge on New York City seeking a way to address climate change, across the U.S. tens of millions are also out of work. The political challenge of achieving a climate policy consensus is hard. There is no broad agreement that the U.S. even has a climate problem. But there is bedrock consensus that we have an unemployment problem, and tackling it may be one of the best ways to help the climate.

Monthly jobs reports indicate U.S. unemployment a little over 6 percent, representing about 11 million people. But that ignores at least another 10 to 12 million Americans who want to work, but are so dejected by the lack of jobs that they have given up looking. The labor force participation rate (the percent of healthy, working-aged adults with jobs) is 62.8 percent, the lowest in 35 years. That means almost 40 percent of Americans are jobless -- many by choice, but many, many others for lack of opportunities.

Factors driving this crisis include a skills/needs mismatch, labor-saving mechanization, globalization, a hangover from the Great Recession and a chronic, self-inflicted problem of double taxation of labor. On top of personal income taxes, our payroll taxes raise hiring costs and encourage employers to use more energy and less labor. Labor and energy/materials are relative substitutes in the overall economy: In general, the more a business uses one, the less it uses the other.

That’s why, even though at first glance jobs and climate seem to be distinct policy questions, they are in fact deeply intertwined. For more than a century through tax policy and other means, development and use of fossil fuels have been incentivized and subsidized. Today with only 5 percent of the global population, the U.S. consumes 20 percent of the world’s fossil fuels. Fees or taxes on energy would cut greenhouse gas emissions more efficiently than regulation, yet we’ve failed to put a price on carbon, and therefore failed to curb energy consumption driving climate change. We currently don’t tax and therefore effectively subsidize climate pollution; but for 75 years we’ve taxed work and job creation, which leads to greater energy consumption and climate pollution.

We could correct this if Congress authorized a modest emission tax or fee on all fossil fuels and other greenhouse gases (GHGs), and used the revenues to offset payroll taxes, which undercut employment. If we started with a fee of $20 per ton of carbon, it would generate $150 billion to $200 billion per year. The level could be adjusted over time to achieve science-based emissions targets to mitigate climate change. Revenues would increase as the rate of taxation increases, eventually flattening out as we reduce consumption and increase energy efficiency.

Revenues generated from carbon fees could be dedicated to a fund to offset part of the Social Security payroll tax for both employers and employees. The payroll tax would remain in place, with most (e.g. 80 percent) of the emissions revenue funding payroll tax rebates. The rest could fund other programs to buffer the impact of higher energy prices on low-income households. This tax shift would be phased in over time allowing firms, governments and households to adapt to new prices through technology changes and shifts in consumption.

This proposal is easily administrable, revenue neutral and market-based, relying solely on the price-induced behavioral changes of producers and consumers. It strengthens Social Security by expanding and diversifying its funding base without threatening or altering its structure, and it expands long-term economic growth by correcting tax-based distortions of the relative prices of labor vs. energy and other inputs to business that aggravate GHG emissions.

Because half of federal payroll taxes are paid by firms and half by employees, reducing them would reduce the cost employers pay for new hires and current workers, and would increase workers’ take-home pay. That will expand labor demand and supply, and keep expanding them over time as firms adjust their production systems. Emissions will shrink as producers and consumers adjust to a new balance between lower labor costs and higher fossil fuel prices, which will incentivize new energy efficiencies and technologies. We’ll be better off economically and environmentally.

The policy key to achieving this is to redraw the inverse relationship between energy use and employment, and keep connecting our need to address climate change to our need to create jobs. They’re twin policy imperatives: To warm less, America must work more.

Image credit: Flickr/Elizabeth Stilwell

Robert M. Wolcott is Senior Economic Adviser to Get America Working and Former Deputy Assistant Administrator for Policy, U.S. EPA.

TriplePundit has published articles from over 1000 contributors. If you'd like to be a guest author, please get in touch!