By Graham Shelby

If you look at the numbers, Kentucky is a place where people smoke more, weigh more and die sooner than almost anywhere in America. The New York Times Magazine recently concluded that eastern Kentucky in particular, “just might be the hardest place to live in the United States.”

My family is from eastern Kentucky, and I recently visited with some of my colleagues from Humana in Louisville. We went there because those of us who’ve spent our lives in Kentucky know that numbers never tell the whole story, particularly when it comes to people’s health.

To understand what’s really happening, you have to talk to people living actual lives in places like Pineville, Middlesboro and Mt. Vernon, people like the man we’ll call Floyd.

A 65-year old Air Force veteran, Floyd met us at a coffee shop in downtown Corbin. He’s part of a small group of people who offered to talk to us about their experience in the Team Up 4 Health program, which our company sponsors.

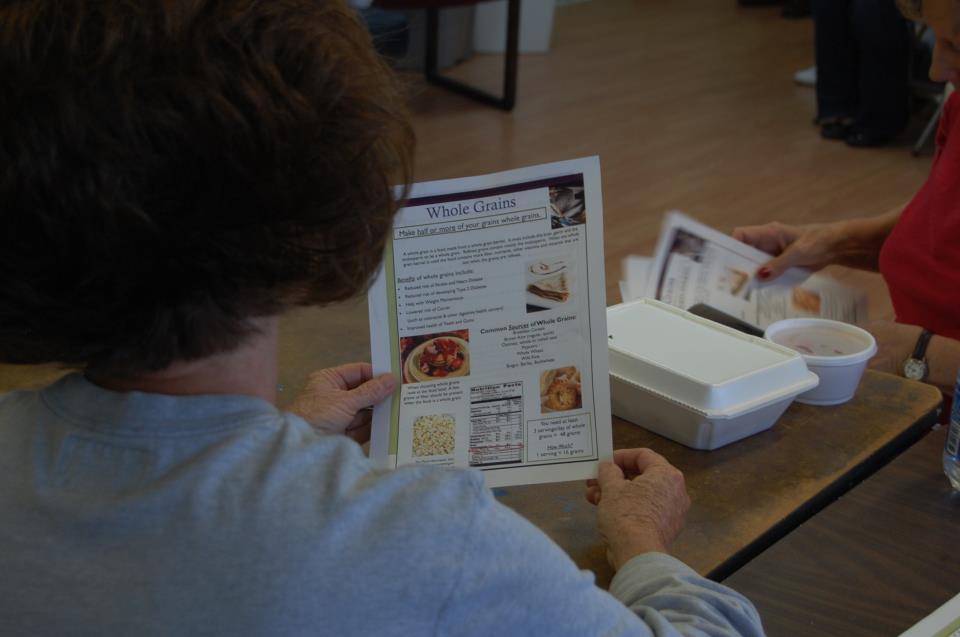

Team Up 4 Health is a public health initiative, operated by the global health nonprofit Microclinic International, that uses an approach based on the notion that people facing chronic conditions like obesity, diabetes and hypertension can work together in groups of friends and relatives to make small changes and significantly improve their health. Microclinic International has run other health programs abroad and set up shop in nearby Bell and Rockcastle counties in part because they’re home to a high concentration of people with chronic health problems.

Floyd, a natural storyteller, told us that at first he wasn’t eager to join Team Up 4 Health, which offers free exercise and nutrition classes to groups of people who enroll together to improve their health.

“I’d thought I was healthy,” Floyd says. In fact, he hadn’t been to the doctor for a check-up in “four or five years.” Floyd’s daughter had to cajole him into attending a session, where the program provided a health screening that got Floyd’s attention. “Turns out,” he says, “I should’ve died six months before that meeting.”

Since joining Team Up 4 Health, he’s followed the program, making a series of small, incremental changes -- eating better, choosing fruits for snacks, walking more. He’s lost weight. He has more energy. “It’s changed my life for the better.”

Humana’s interest in Team Up 4 Health centers in part on the changing dynamics of American health care. In both social and economic terms, greater health for people like Floyd is everyone’s interest – insurers, the community, and the patient himself and his family. If Floyd had ended his story there, we would have been satisfied that we’d heard all we need to know. But Floyd had more to say.

“Of course, I am still smoking,” he says. He has for most of his life. In discussing it, he’s alternately contrite and defiant. He knows it’s bad, knows he’s setting a poor example for his kids and grandkids. He also declares, “If my doctor told me, ‘Give up cigarettes, or in six months, you’ll be dead,’ I’d tell him, ‘Well, then, let’s make the funeral arrangements right now.’”

This makes me wince, in part because the sentiment is so familiar. Deep within the character of this region, if not of America itself, lies an ornery streak. Floyd knows that tobacco hurts his health, yes, but it’s still his health. His life.

What Floyd makes clear, intentionally or not, is that changing health habits is only partly about disseminating information about carbohydrates or sodium content. It’s perhaps just as much about identity. Getting Floyd to give up smoking isn’t just about changing what he does; in some sense, it’s about changing who he is, or at least how he sees himself.

What I want to say to Floyd, but don’t, is the same idea I often struggle to remind myself: that my identity as a human being, or a man, is not so fragile that it can be either lost or salvaged by anything that comes from a cigarette pack or a snack machine.

Given the complex nature of culture, health and identity, the results Team Up 4 Health have achieved here look even more impressive. In the initial two-year pilot in Bell County, 95 percent of participants who completed the program reported improved numbers in one of the program’s key metrics, like waist circumference, BMI or blood glucose.

I notice Floyd’s smoking comment earns him a withering look from the woman sitting next to him in the coffee shop. She’s part of his Team Up 4 Health group. They earn points and prizes for their team’s ability to meet health goals. Her success is tied to his. In a way, so is ours as a society. The sicker we are as a people, the harder it is for our health care system to take care of us, and the greater the drag on the respective economies of towns, states and the nation.

In the weeks since that visit, I’ve thought about Floyd often and hope that he takes care of himself. Like all of us, one day, all that will be left of Floyd will be those kids and grandkids and their memories of him. When that happens, it’d be nice if one of the Floyd stories they tell goes something like this:

“Remember how he used to eat everything and smoke all the time?”

“Yeah. He really turned that around, though, didn’t he?”

“Mm-hmm, it was something to see.”

Image credit: Team Up 4 Health via Facebook

Graham Shelby is a communications consultant for Humana. He also writes about personal health and fitness at blog213.com

TriplePundit has published articles from over 1000 contributors. If you'd like to be a guest author, please get in touch!