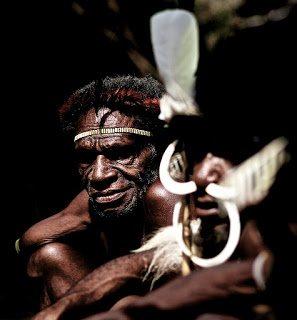

Given our dependence on the products of highly sophisticated science, engineering and technology, it's easy to pay short shrift, or look askance, at the value of traditional indigenous knowledge. To be sure, the depth and scope of our knowledge has advanced rapidly. Yet, this type of arrogance, or hubris, not only takes away all that could be gained scientifically and socially from an unplumbed yet certainly rich cultural heritage, but may leave us more open to being blindsided by “black swans.”

Traditional indigenous knowledge, as well as human resources, holds particularly high value with regard to ecological and species conservation, and efforts to preserve rapidly diminishing biodiversity. Still directly connected with natural ecosystems for their livelihoods, the practical, everyday ethics, values and attitudes of traditional indigenous cultures can also inform and motivate our quest to enhance the overall sustainability of modern life and society, and add shared value and meaning to them.

Looking to tap into and incorporate traditional indigenous knowledge into its institutional framework, the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity's (CBD) Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) convened an international expert workshop on the contribution of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) to IPBES in Tokyo June 9-11.

Science, indigenous peoples and conserving biodiversity

With 194 United Nations (U.N.) member countries and the EU parties to it, the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity is the principal multilateral treaty for governance of biodiversity. Modeled after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the recently established Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is its operational branch.

With species and biodiversity diminishing at alarming rates, the CBD secretariat, along with agencies including the U.N. Environment Programme (UNEP), has been expanding efforts to incorporate traditional indigenous knowledge into the process of formulating treaties and policies regarding international environmental governance, as well as financing and otherwise supporting projects on the ground.

As UNEP reports in The Contribution of Indigenous and Local Knowledge Systems to IPBES: Building Synergies with Science:

“In the face of unprecedented declines in biodiversity over past decades, it has become increasingly apparent that synergies must be built among knowledge systems in order to provide policy-makers and science practitioners with the best available knowledge to decide what urgent action must be taken to halt the rapidly accelerating degradation and loss of the biodiversity and ecosystem services that underpin sustainability, as well as resilience in the face of global change.”

Integrating indigenous and local knowledge with modern science

Toward that end, participants at IPBES' expert meeting in Tokyo began a process to officially and formally incorporate indigenous and local knowledge into the organization's emerging institutional framework for multilateral biodiversity and ecosystems services governance. Two initial recommendations broadly set out the means of doing so:

- Recognizing that indigenous peoples and members of local communities have distinct status as knowledge-holders and rights-holders; and

- Putting in place mechanisms and procedures to ensure effective participation in the MEP (Multidisciplinary Expert Panel) itself and its activities, including in any working groups, expert bodies and other structures that may be established, in the development of the conceptual framework and work program, as well as in outreach to indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs).

A commitment to gender equality was also elaborated. As stated in UNEP's report, “Women and men commonly fulfill different, but complementary roles and responsibilities in relation to different components of biodiversity and sustainable use, resulting in different knowledge, needs, concerns, priorities and roles.

“For this reason, women may possess knowledge, not held by men, which can inform IPBES processes. To fulfill its operational priority to achieve gender equity in all relevant aspects of its work, IPBES should put in place mechanisms that ensure attention to gender specific-knowledge and gender balance in all components of its work.”

A commitment to undertake an ambitious work program aimed at integrating indigenous local knowledge with modern science also came out the expert meeting in Tokyo. This includes carrying out a scoping study “of existing experiences, approaches and methodologies on bridging between scientific and indigenous knowledge systems to better understand and assess status and trends with respect to biodiversity and ecosystems services.”

Concerned with issues such as bio-piracy, IPBES also made a commitment to enhance efforts related to intellectual property rights, access and benefit-sharing, and free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), the fundamental principle underlying an ethical commercial framework for obtaining rights to make use of indigenous knowledge and methods, as well as products resulting from research on local flora and fauna.

Images credit: 1) The Coincidental Dandy; 2) The Global Change Project; 3) NovaMind

An experienced, independent journalist, editor and researcher, Andrew has crisscrossed the globe while reporting on sustainability, corporate social responsibility, social and environmental entrepreneurship, renewable energy, energy efficiency and clean technology. He studied geology at CU, Boulder, has an MBA in finance from Pace University, and completed a certificate program in international governance for biodiversity at UN University in Japan.