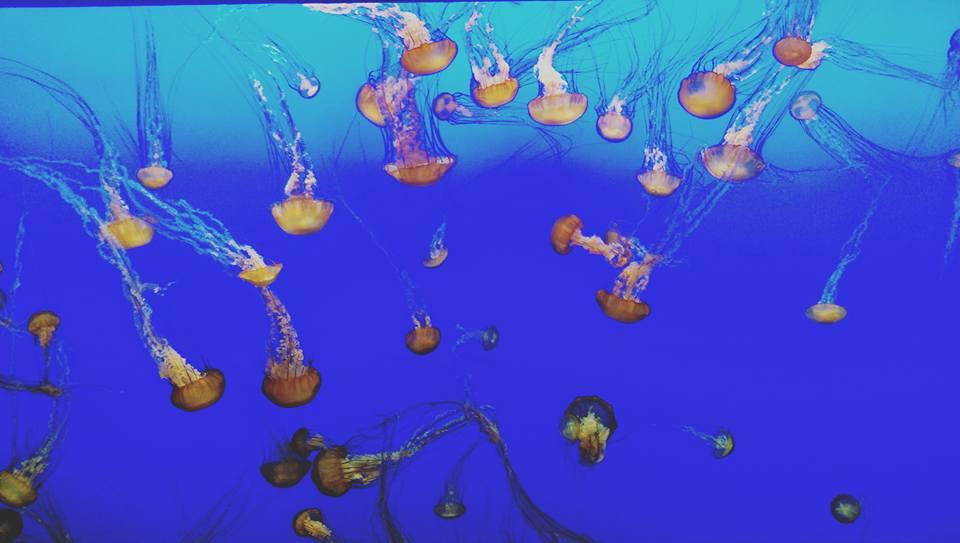

The science behind the surge in jellyfish populations across the world’s oceans is under debate. Nevertheless, whether the leading causes are overfishing, climate change, acidification or pollution, jellyfish blooms are on the rise and have wreaked havoc from Australia to Scandinavia. One writer has even suggested jellyfish themselves are helping to fuel climate change, as the waste they generate creates more carbon dioxide, which reduces the populations of plankton, the microscopic-sized organisms critical for their role in the removal of CO2 from the world’s oceans and atmosphere.

Meanwhile, jellyfish clog pipes connected to a nuclear power plant in Sweden, shutter aquaculture operations and have made it difficult for natural fishing stocks to recover. Organizations such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium have accelerated research and launched sites, such as the “Jellyfish Watch,” to track this ongoing threat to local ecosystems and marine life, but so far this ongoing problem has proven to become too large to control.

One start-up in Israel, however, has seen an opportunity in the jellyfish blooms that have been insidious across the Mediterranean Sea in recent years.

Cine’al, based in Tel Aviv, believes it has found a use for the jellyfish that suddenly wash ashore in massive numbers, or as in the case several years ago, compromised a nuclear plant’s pipes in the northern coastal town of Hadera.

Jellyfish are highly absorbent, as they are comprised of 90 percent water. This absorbency inspired Shachar Richter of the University of Tel Aviv to test them out for their usefulness in consumer products. The result is a material that Richter developed called “hydromash,” a material Cine’al claims is more effective at absorbing materials than conventional paper-based products. The dried jellyfish are churned into a fibrous material that is naturally antibacterial, flexible and can help skin heal quickly when used in products such as bandages. Better yet: when hydromash is used in disposable diapers, Cine’al claims that these discarded products can biodegrade in 30 days or less.

Contrast that rate with that of conventional disposable diapers, which according to most sources, take anywhere from 250 to 500 years to decompose. As one of Cine’al’s executives explained to a local newspaper, if this hydromash process can scale, the long term result will be a win-win. Jellyfish are washing up on shores, leaving a negative impact on the tourism and aquaculture industries; meanwhile, diapers are taking a significant amount of space in landfills.

The harvesting of jellyfish could also complement the global pulp and paper industry. While the vast majority of paper products come from managed forests, a growing population worldwide always leaves the door open for additional deforestation. The trick, however, is market acceptance and getting over the “ick” factor. And forget about growing demand for vegan products, as an animal-based paper towel, bandage or tampon will be a non-starter for some consumers.

Nevertheless, a solution is needed, as the evidence suggests jellyfish blooms will not recede anytime soon. Some observers have suggested harvesting more jellyfish as a food source, as they contain some nutrients such as collagen and amino acids. Several Asian cuisines showcase this translucent creature: a shredded jellyfish salad is a mainstay side dish in Korea. Other companies have harvested jellyfish for use in beauty products, but those anti-aging creams and lotions have not caught on with many consumers.

The reality is that the world needs to take far more aggressive action on our oceans and the global seafood industry if society is going to avert a massive marine disaster. But this change in the world's oceans also opens up new business opportunities – which can contribute to the healing of the seas in the process.

Image credit: Leon Kaye

Leon Kaye has written for 3p since 2010 and become executive editor in 2018. His previous work includes writing for the Guardian as well as other online and print publications. In addition, he's worked in sales executive roles within technology and financial research companies, as well as for a public relations firm, for which he consulted with one of the globe’s leading sustainability initiatives. Currently living in Central California, he’s traveled to 70-plus countries and has lived and worked in South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay.

Leon’s an alum of Fresno State, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and the University of Southern California's Marshall Business School. He enjoys traveling abroad as well as exploring California’s Central Coast and the Sierra Nevadas.