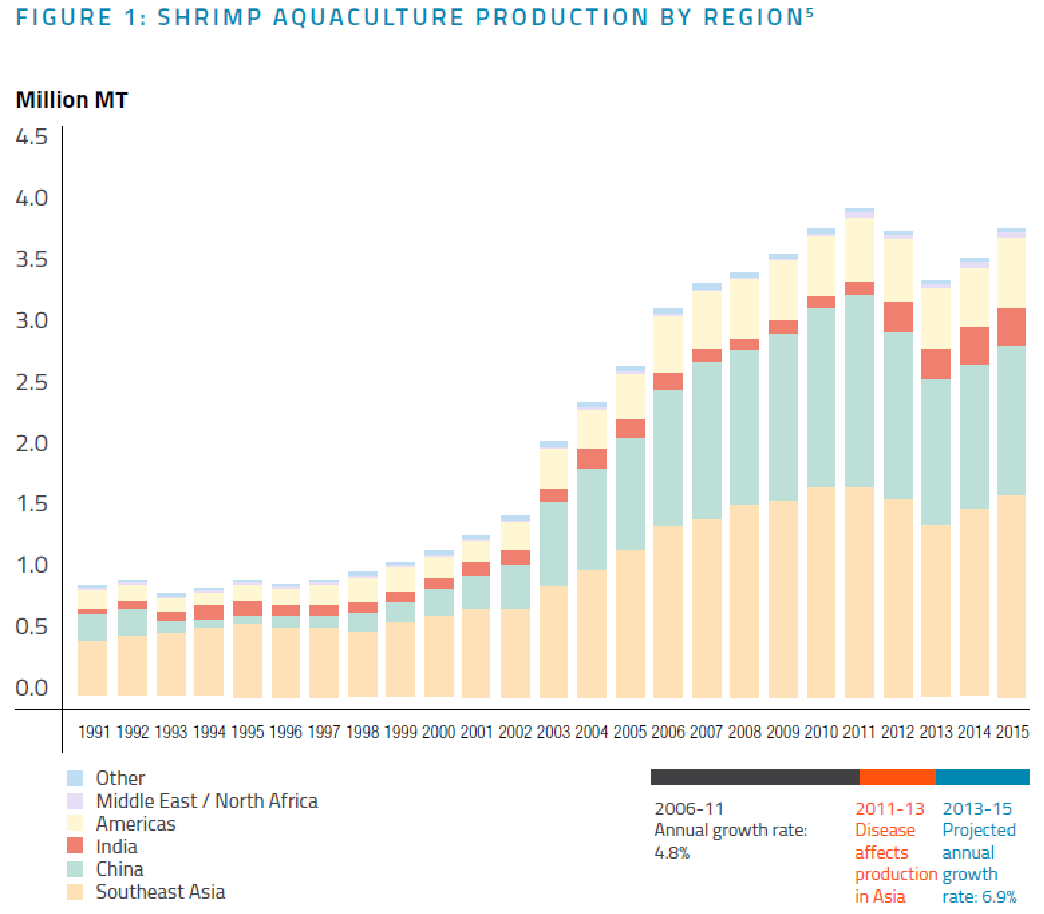

Thanks in large part to aquaculture, global shrimp production has increased by an average 13 percent per year since the 1980s. Prices have dropped nearly 30 percent. That's turned shrimp from a luxury food item into one of the most popular and affordable seafood products in the world -- and made shrimp aquaculture a lucrative and important industry in Asia and other developing regions.

While the benefits of lower prices and greater availability are clear for consumers to see, the social and environmental costs associated with shrimp aquaculture and fishing are often not. As a report from CSR Asia highlights, shrimp production as it's being practiced today is associated with environmental degradation, excessive use of antibiotics and chemicals, and land grabs -- not to mention scandals revolving around slavery and human trafficking.

In “Opportunities for Inclusive Business: A Case Study of the Shrimp Value Chain,” CSR Asia brings to light 10 key challenges facing the shrimp industry in three of the world's leading shrimp producing nations, then goes on to identify “possible entry points and interventions for inclusive business opportunities.”

Shrimp fisheries and sustainability

Shrimp is the world's most valuable seafood product, accounting for about 15 percent of the total value global fisheries products in 2010. Of the world total, 45 percent were wild-caught shrimp, which provided livelihoods for an estimated 900,000 fishers worldwide, CSR notes in its report.

The majority of shrimp are raised on small-scale, open-air farms, mostly in developing countries, where the costs of land and labor are relatively low. Falling shrimp prices have been raising the pressure on shrimp farmers, leading them to decrease already-low wages for the predominantly poor residents and migrants who work for them.

In its report, CSR Asia zooms in on the shrimp fishers, farmers, processors and processes in three leading shrimp-producing nations: Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia, the world's second, third and fourth largest shrimp producing nations after China, the world's largest.

There are some important differences among these leading shrimp-producing nations, however. China's shrimp production is mostly consumed domestically. Most of the shrimp produced in Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia, in contrast, is exported to major markets in the U.S., Japan and the European Union (EU). Thailand is the world's largest shrimp exporter.

10 critical challenges

Greater awareness of economic, social and environmental problems along the shrimp value chain has led to increased scrutiny by international NGOs and other public interest groups, which are exerting pressure on governments and multinational businesses to take actions that could resolve them.

The fact that the shrimp is industry is made up of many small enterprises with low revenues makes this all the more challenging, CSR Asia points out, but the seriousness of the problems merit prompt, concerted action.

“Whilst the complexity and limited transparency of the shrimp value chain may make it difficult for companies to take action, it is clear that ‘business as usual’ is neither sustainable nor consistent with increasing the incomes of poor people involved in shrimp fishing, farming and processing.”

CSR Asia identifies the following as the 10 critical challenges facing shrimp industry participants:

- Overfishing

- Fishing practices

- Mangrove destruction

- Pollution

- Ecosystem disruption from introduction of non-native species

- Disease

- Consumer health and food safety

- Human rights

- Child labor

- Land grabs

In turn, these ills bring along a host of associated business risks, CSR Asia notes. These include risks to reputation and the sustainability of supply and food security, the risk of embargoes and tariffs, volatility in prices and quality, the risk of worker protests, and the risks associated with ineffective implementation of industry standards.

Possible entry points for inclusive business

In its report, CSR Asia urges the entire spectrum of stakeholders to actively seek out “opportunities to develop much more inclusive value chains that can better involve the poor and increase benefits accruing to them.” As the report authors state:

“Businesses, consumers, NGOs,development organizations and local governments can work together to find solutions to problems through examination of new opportunities for inclusive business.”

CSR Asia defines inclusive business as “a sustainable business model that includes the poor in commercial value chains as producers, suppliers, distributors, employees, business owners and customers in ways that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously improving economic, environmental and social conditions in the communities in which it operates.”

An inclusive business strategy for the shrimp, or any, industry, CSR continues, requires “a package of interventions, including access to finance and capacity building for small fishers, farmers and processors.”

Leading companies along the shrimp industry value chain, CSR Asia asserts, “can help to increase the incomes of small producers and workers at the same time as modernizing the industry, ensuring improved labor practices, integrating sustainability factors and improving the traceability of products.”

So can other key stakeholders, including government, community leaders and NGOs. CSR Asia identifies 10 possible entry points that stakeholders can leverage in executing an inclusive business strategy.

*Image credits: CSR Asia

An experienced, independent journalist, editor and researcher, Andrew has crisscrossed the globe while reporting on sustainability, corporate social responsibility, social and environmental entrepreneurship, renewable energy, energy efficiency and clean technology. He studied geology at CU, Boulder, has an MBA in finance from Pace University, and completed a certificate program in international governance for biodiversity at UN University in Japan.