Most of us assume that it's better for the health of the planet if we buy our food locally. After all, those bananas we purchase each week travel many miles by ship to get to our breakfast table. And that chicken we bought for tonight's dinner most likely arrived courtesy of a lengthy supply chain across the country. So did the tomatoes that arrived from farmlands in Mexico.

But the fact is: Calculating the environmental impact of our food purchases isn't always as simple as figuring the driving distance to the nearest point. Rich Pirog, the senior associate director of Michigan University's Center for Regional Food Systems, is credited with helping to debunk that generalization.

According to his early research on the transportation impact of shipping perishable foods, the fact that food was shipped across the country or across the world doesn't tell the whole story when it comes to the environmental impacts of food shipments. The real issue, said Pirog, is the method that was use to ship the product: whether it arrived by air, by ship, by rail or by land. And even then, say some researchers, small-scale local production doesn't always win out over large-scale operations that have better transportation systems and food preservation methods at their fingertips.

Since Pirog's initial research in 2001, a plethora of studies were conducted on this subject, particularly when it comes to perishable foods that can't simply be crated and put on a ship or rail, like bananas can. Tomatoes that were grown in greenhouses in Sweden's variable climate actually required 10 times the energy usage than those shipped in from the sunny fields of Southern Europe. Similarly, researchers found that it wasn't the refrigeration or the fuel that was required to ship beef, chicken or eggs to supermarkets that hiked the carbon emissions, but rather the production and processing of fresh meats and eggs at the point of origin. When it came to meat products, transportation (including the refrigeration of the product) resulted in only about a 1- to 2-percent rise in energy costs. Fresh produce was the most expensive to transport at 11 percent.

And the process that is used for growing, and storing, produce weighs into that cost as well, as a 2008 study showed when the authors compared how apples are grown and handled in different countries. Apples that were lost in production from seasonal weather and other issues figured into the energy costs, as did the way they were farmed, how they were marketed and what methods were used in pest management.

Food loss and waste accounts for as much as a third of the world's production, but even adjusting our finicky eating habits can't erase the loss that comes when adequate protections aren't available or aren't used in distribution.

As much as 20 percent of the sub-Sahara's grain production is lost each year due to spoilage. When it comes to insufficient refrigeration and preservation in Latin American countries like El Salvador, Colombia, Trinidad and Belize, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that if all food loss were eradicated, those countries would have enough food to meet their First Millennium Goal, a crucial consideration for food security in developing nations.

Here in the U.S., as much as 12 percent of retail food products is lost to spoilage or other issues on its way from the retailer to the consumer. But it is a small percentage when considering what goes into the dumpster once it is sold to the consumer. A whopping 28 percent is lost due to spoilage, waste and inedible material (stems, peelings, seeds or fruit membranes we were raised not to consume), after the perishable items leave the store with the consumer.

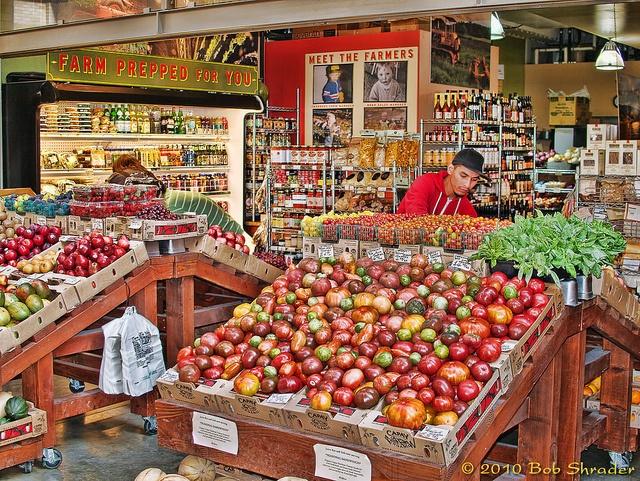

Pirog and other researchers point out that buying locally can have its benefits when it comes to slimming down the overall energy and emissions costs. Buying locally-grown fruit in British Columbia, Canada, for example, where a major agricultural industry makes it easy to purchase fresh apples from the local corner store, makes more sense, perhaps, than purchasing Washington or Japanese varieties. But with today's packaging and shipping systems geared toward expedited delivery and minimizing food loss, product refrigeration and preservation makes up only a small percentage of the energy that is spent in getting perishables to their destinations.

The real challenge, say experts, is retooling the way we look at the value of the food we purchase, and our collective part in ensuring a well-fed and sustainable planet.

Images: 1) Bob Shrader; 2) David Stanley; 3) Taz; 4) A Davey.

Jan Lee is a former news editor and award-winning editorial writer whose non-fiction and fiction have been published in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the U.K. and Australia. Her articles and posts can be found on TriplePundit, JustMeans, and her blog, The Multicultural Jew, as well as other publications. She currently splits her residence between the city of Vancouver, British Columbia and the rural farmlands of Idaho.