Do you remember from your high school science class how photosynthesis converts sunlight, carbon dioxide and water into sugars? Algae creates sugars really quickly, making it an appealing feedstock for ethanol and other biofuels. Pond scum may one day power your car.

Algae-based biofuels have numerous pros and cons when compared to other sources of biofuels and oil products. Algae can be grown all year long and doesn't require petroleum-based fertilizers. Algae ponds, however, can be expensive and difficult to manage, and the process requires carbon--making it dependent on fossil fuels. The viability of algae-based fuels however varies widely by the process, and some closed systems processes seem very promising.

"Not all algae can be lumped together," says Paul Woods, CEO of Algenol, a biotechnology company that produces ethanol and other fuels. "There are lots of [algae-based biofuel] programs that use fresh water and open ponds that have high evaporation rates, even if they use brines. Algenol has a closed system. Ethanol evaporates. If we had an open system, we would lose all our product and because it is closed, it isn’t subject to evaporation."

Paul Woods gives many convincing reasons why Algenol's patented technology creates a high-yield product, without large amounts of fresh water or cropland, to power our vehicles. In fact, Woods says the Algenol process has yielded over 10,000 gallons of fuel per year at its pilot-scale facility in Fort Myers, Fla. After ethanol is produced, waste algae is used to produce smaller amounts of jet fuel, diesel and gasoline. Corn produces a measly 420 gallons of ethanol per acre, per year. In addition, algae can also be cultivated on land that isn't suitable for other agriculture.

"Here in Florida, when you dig a well down, you can connect directly to the ocean, like a filtered straw," says Woods. "We go down 1,800 feet, we pull directly from the aquifers going into the ocean, which isn’t suitable for agriculture because it is way too salty."

A large plant would a have one or two hundred workers, because the process is automated. Many more temporary jobs are created, however, to construct a commercial facility.

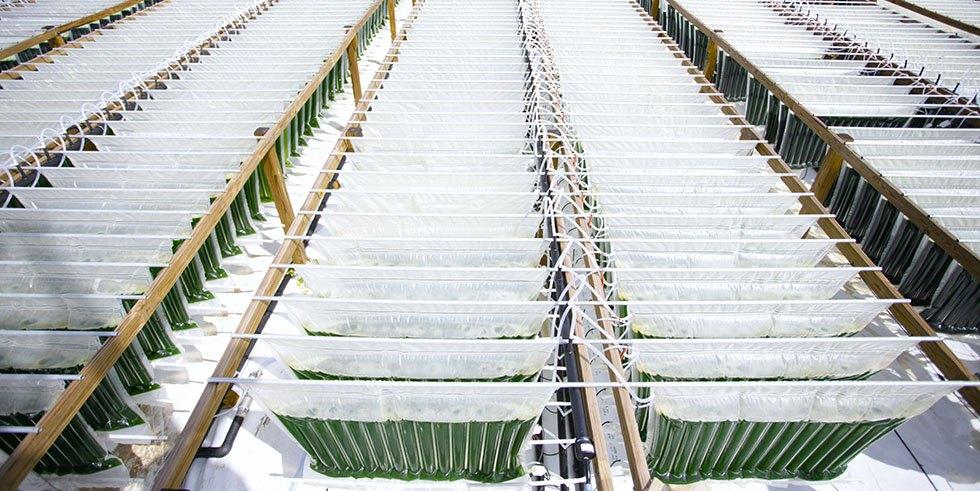

The Algenol process requires algae, saltwater and carbon dioxide. A natural gas power plant flue is an ideal source for the carbon dioxide required in the process. Instead of using a pond, the closed system occurs within a plastic bag.

"We have a 50-liter bag," explains Woods. "We have a lot of them, and that’s a very small amount of culture to manage. We do all of our scale-up through replicating the same module over and over again. "

"We have two strategic investors in our company," says Woods. "One of them operates the largest refinery in the world. They have 20,000 engineers on their staff. They've had significant input into the scaling up of our technology." Algenol previously partnered with Dow Chemical, but ended the relationship in 2010.

Algae biofuels critics point out that algae simply cannot generate enough ethanol to generate fuel to power the world. Woods seems to agree.

"I think the bigger picture is: How are we going to supply the energy to an expandig middle class on this planet, without having the entire planet covered in coal power plants? That’s the real challenge. Even if I put up as many Algenol plants as I could possible do, it would still just meet the incremental demand."

Image credit: Algenol

Sarah Lozanova is a regular contributor to environmental and energy publications and websites, including Mother Earth Living, Green Building & Design, Triple Pundit, Urban Farm, and Solar Today. Her experience includes work with small-scale solar energy installations and utility-scale wind farms. She earned an MBA in sustainable management from the Presidio Graduate School and she resides in Belfast Ecovillage in Midcoast Maine with her husband and two children.

Sarah Lozanova is an environmental journalist and copywriter and has worked as a consultant to help large corporations become more sustainable. She is the author of Humane Home: Easy Steps for Sustainable & Green Living, and her renewable energy experience includes residential and commercial solar energy installations. She teaches green business classes to graduate students at Unity College and holds an MBA in sustainable management from the Presidio Graduate School.