Twenty-five states and the District of Columbia now have laws on the books that legalize marijuana in some form. Most regulate consumption of marijuana for medical needs; only Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington have legalized pot for recreational use. Despite the fact that many local law enforcement officials believe any focus on marijuana prevents them from working on more pressing community needs, ingesting cannabis in any form is still a crime under federal law.

Marijuana use is still an offense within the world of professional sports; just about every professional league or athletics association says cannabis is a no-no under their blanket policies related to drug use. The absurdity reached a fever pitch during the 1998 Winter Olympic Games in Nagano, Japan, when snowboarder Ross Rebagliati of Canada almost lost his gold medal because he tested positive for marijuana use. Rebagliati kept his medal, but he was not allowed to enter the U.S. for years because of his affinity for pot.

While the world tut-tutted, some observers sneered that telling snowboarders to avoid pot was akin to lecturing surfers to avoid waves; others wondered what the point was of banning a substance that in many cases would have no effect on, or may even impede, athletic performance rather than improve it. Meanwhile, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 88,000 Americans die annually due to alcohol abuse — but no one has ever been suspended after testing positive for downing a few cold ones before a match. Such a rule would infuriate the likes of AB Inbev, as its iconic brand, Budweiser, is a sponsor of many a sporting event.

Rebagliati now wants to sell medical marijuana in Canada, and he's speaking out aggressively after being shamed into silence for years. And south of the border, another star athlete, once highly touted then widely mocked, also wants the sporting world -- and society at large -- to accept cannabis for what he and his allies say are its health benefits.

Ricky Williams was a standout at the University of Texas, where he won the Heisman Trophy in 1998. Legendary coach Mike Ditka traded all of the New Orleans’ Saints 1999 draft picks to select Williams in that year’s National Football League draft. Williams had some success in New Orleans, but was traded to the Miami Dolphins after a few years. Then in 2004, Williams tested positive for marijuana, for which he was suspended from play and paid a massive fine. Rumored to have failed another test, he retired later that year. Williams spent a year out of the NFL, enrolled in an ayurvedic medical course in California and traveled the world. He eventually returned, got caught again, was suspended for year, then eventually played football in Canada and again for the Baltimore Ravens before retiring for good in 2012.

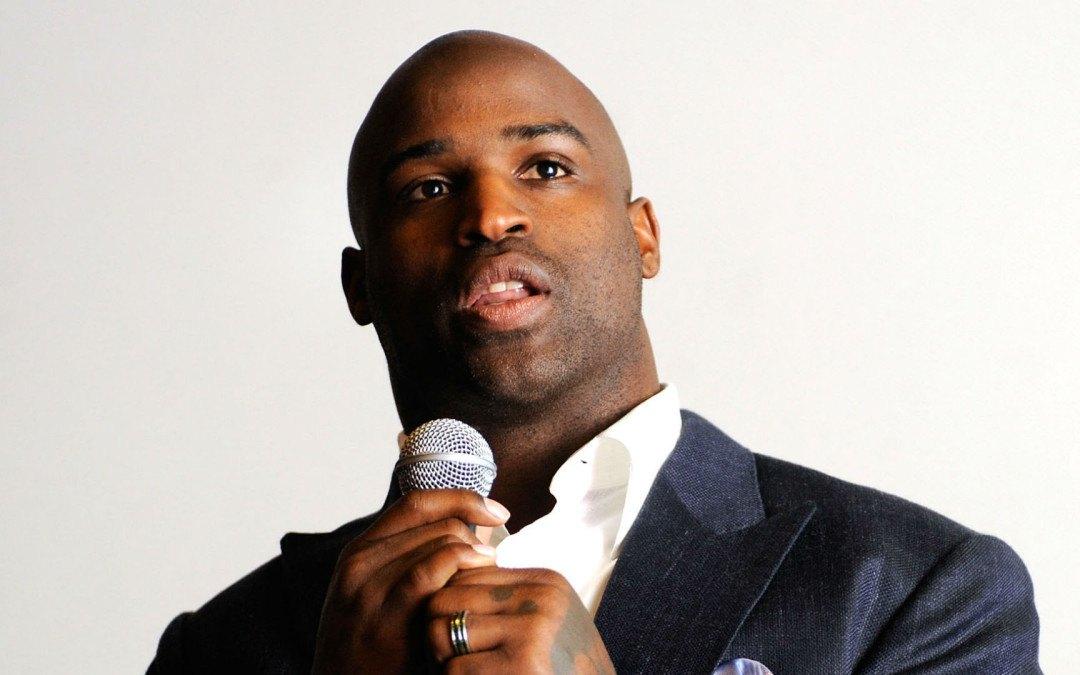

Despite his muscular build, clean-cut looks and overall appearance that hardly imparts that he is a “stoner,” columnists and Internet trolls alike have ridiculed his marijuana use for years.

Williams has been quoted in the media time and again saying that marijuana helped him cope with depression, social anxiety disorder and the physical pain resulting from playing football. And now he is seeking to make marijuana use mainstream for athletes, and in reality, anyone.

First, Williams has become the spokesman for the Four-Twenty Games, a series of athletic events due to relaunch this summer that will strive to prove that marijuana users are not the stereotypical flannel-wearing stoners who are lazy and unmotivated. The organizers of these events, who started with a small gathering in 2014 that attracted 200 people, say they will bring as many as 10,000 participants to six cities in California, Colorado, Oregon and Washington.

In addition, Williams also partnered with another investor, Jim McAlpine, to open what this group describes as the world’s “First Cannabis Gym” in San Francisco. Scheduled to open this autumn, Power Plant Fitness will integrate athletic workouts with mind training and well being. Members will be permitted to consume marijuana in any form during their workouts. The gym’s staff will also offer a product line of “athletic edibles” for both exercise preparation and post-workout physical recovery.

To that end, writer Joel Warner called out the NFL for its puritanism (and the kerfuffle over draft pick Laremy Tunsil’s apparent loss of $8 million after a video clip of him wielding a bong hit Twitter), while praising Williams as staying true to himself and opening a venue where those who use marijuana can feel welcome, not ostracized.

So will this gym be, pardon the pun, a hit? The world of athletics has long been one riddled with hypocrisy, as its ambassadors tout patriotism, clean living and on-field heroics while glossing over life-threatening injuries, numerous individual bankruptcies, the emotional blackmailing of cities so that they will publicly fund underused stadiums, and domestic violence.

But attitudes are changing. Even politicians have realized that the obsession with criminalizing a plant has caused society more grief than gain. Former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson, who has long ditched the Republicans and could be a factor in this year’s presidential race as a Libertarian candidate, boasted about his investments in -- and consumption of -- marijuana. We have come a long way from the days when Hillary Clinton’s husband told the world he “didn’t inhale.” To many cannabis users, it is now time for professional sports to grow up, too.

Image credit: Four-Twenty Games

Leon Kaye has written for 3p since 2010 and become executive editor in 2018. His previous work includes writing for the Guardian as well as other online and print publications. In addition, he's worked in sales executive roles within technology and financial research companies, as well as for a public relations firm, for which he consulted with one of the globe’s leading sustainability initiatives. Currently living in Central California, he’s traveled to 70-plus countries and has lived and worked in South Korea, the United Arab Emirates and Uruguay.

Leon’s an alum of Fresno State, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County and the University of Southern California's Marshall Business School. He enjoys traveling abroad as well as exploring California’s Central Coast and the Sierra Nevadas.