Biomimicry, the design and production of materials, structures and systems modeled on biological entities and processes, is one example of how Mother Nature knows best. Breakthroughs in this field are touted as being one way to achieve a circular economy and solve other environmental challenges. That’s why the Biomimicry Institute and the Ray C. Anderson Foundation launched the Biomimicry Global Challenge and created the $100,000 Ray of Hope Prize in 2014. This partnership’s goal is to help bring nature-inspired technologies to market.

Doing a world of good with biomimicry

According to Beth Rattner, Executive Director of the Biomimicry Institute, nature has the answers to solve many of the world’s problems. Businesses embracing nature’s designs can do a lot of good as evident with the Ray of Hope finalists, who spend a year working with experts and mentors through the Institute’s Biomimicry Launchpad. The 2019 finalists were:

Aruga Technologies (Pittsburgh, PA) has developed a vascular implant technology with double the implant life that takes advantage of nature’s dynamic surface wrinkling found in dolphins (prevents fouling from barnacles and algae) and other creatures. In the case of human arteries, as the surface wrinkles and straightens, debris (such as platelets) is cast off, renewing the surface.

Other potential applications include water filtration and petrochemical processing, replacing conventional chemical coatings and expensive cleaning processes used in these applications. Aruga received a $25,000 second prize from an anonymous donor.

Another treatment technology is being developed in India, where the majority of sewage goes untreated. The EcoStp team from Bangalore has come up with a low-maintenance technology inspired by the four chambers of a cow’s stomach. Instead of using high-energy equipment like motors, fans, pumps and blowers found at a conventional treatment facility, bacteria, plants, and gravel filters are used to treat sewage. Better yet, the technology produces energy instead of consuming it and has the potential to treat up to one million liters of sewage a day without needing to be connected to a power grid.

Two teams from California State University-Long Beach were also finalists:

- Gen-Rail adapted features of three diverse creatures (cockroach, California condor and desert snail shell) to harness wind generated on urban freeways and convert it into energy. Gen-Rail claims its system has a small environmental footprint, is highly efficient and will be easy to implement in cities.

- Phalanx Insulation looked to the cactus, cathedral termite and several Saharan creatures (silver ant, camel) for designing its insulation grid, which is applied to exterior walls of existing buildings. This system reduces interior temperatures of buildings passively without the need for electricity by removing hot air and moisture.

Finding more solutions with flora

Several finalists took their inspiration from plants for their technologies. Habari (Utrech University, The Netherlands) is addressing the billions of dollars in potential frost damage to tea plants in Kenya with technology adapted from several of that country’s native mountain plants. Triggered by temperature, the system automatically deploys a mesh where frost deposits, covering the plants and preventing the frost from settling on the leaves.

The inspiration of a carnivorous plant is helping to do good in a different way. Every year, more than 600,000 people die from malaria. To reduce this number, Cornell University designed its device based on the bladderwort plant, which uses vacuous pods on its roots to trap small insect prey. The UPod is a solar-powered mobile device that pulls water and mosquito larvae into a tightly-sealed water chamber, where the larvae are destroyed.

Grand prize winner looks to the sea

A fifth of clean water produced globally is lost to leaks every day. WatchTower Robotics Co. (Boston, MA), the recipient of the $100,000 prize, incorporated features of three marine creatures in their patented robotic technology to address this loss:

- Blind cave fish. The animal senses changes in water pressure using hair cells to ‘see’ the surroundings. The silicon flappers of the robot mimic this process.

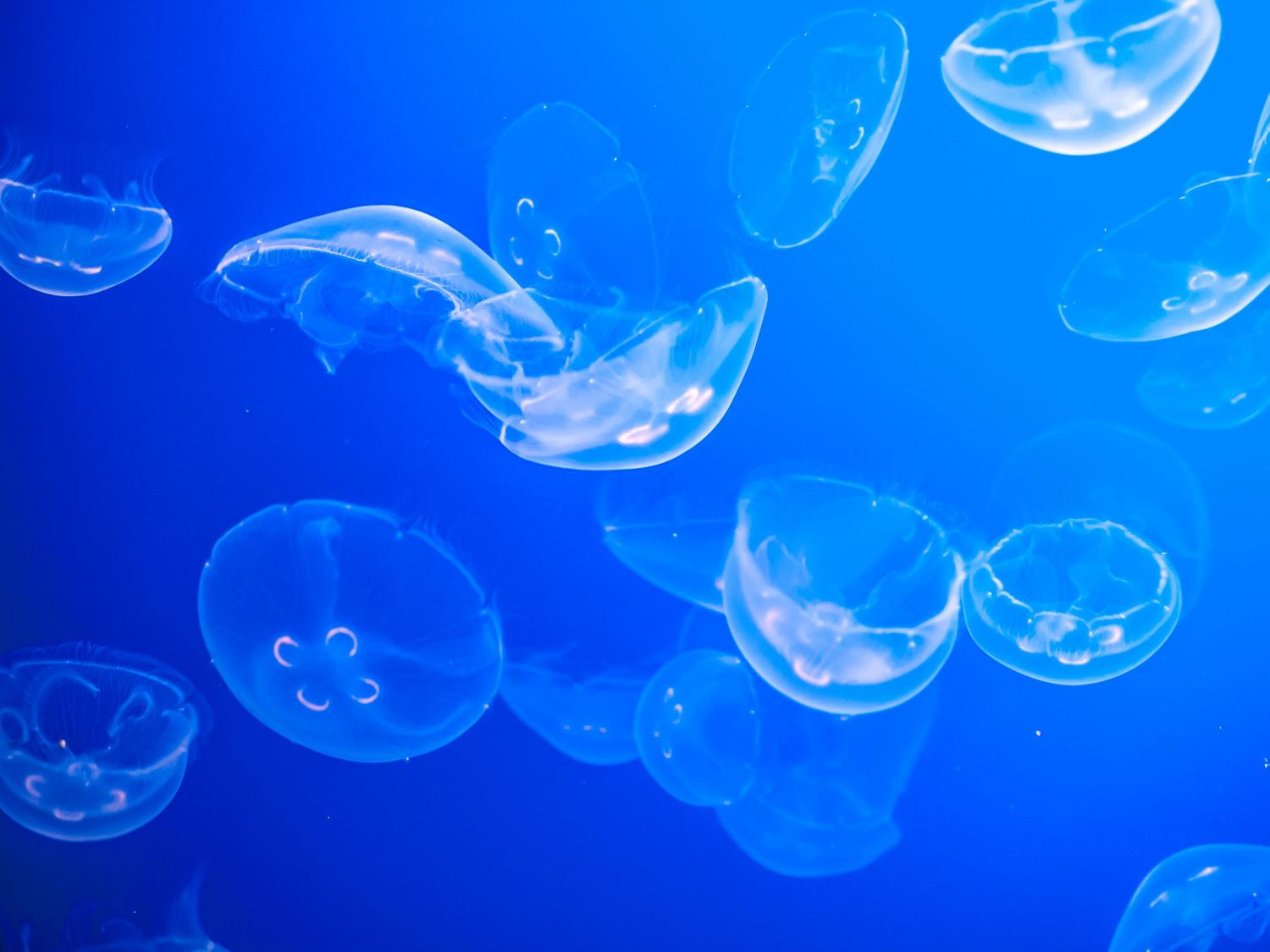

- Moon jellyfish (shown above). A pulsating umbrella-shaped bell propels the animal through the water. The robot also uses umbrellas at two locations to move the robot through the pipes without using any energy.

- Octopus. Because of its soft invertebrate body, an octopus can squeeze through tiny cracks and holes. The robot is also soft without joints, allowing it to bend and shrink to 50 percent of its original size, Octopus-like suckers on its flappers also help the robot maintain contact with the pipe wall and identify leaks.

The robotic system maps pipe systems in three dimensions and WatchTower claims it has five times the speed of traditional leak detection at a tenth of the cost.

So what unique animal or plant will lead to another innovative design? Stay tuned to see what next year’s finalists come up with and who will take the grand prize.

Image credit: William Warby/Flickr

Laurel has extensive experience writing about energy efficiency, clean energy, sustainability and green building. She was formerly Senior Energy Content Specialist for a digital marketing firm serving the utilities industry where she generated story ideas and wrote content for several e-newsletters. Laurel is also a member of the Ohio chapter of the U.S. Green Building Council and participates on several committees for the Central Ohio region.